Highlights

- Stigma is a barrier to engaging in care for gambling problems.

- Financial problems were stigma-related barriers to seeking help for men and women.

- Addictive qualities of gambling and emotional distress created barriers to care for men.

- The seductive gambling environment was a stigma related barrier to care for women.

- Gendered views of stigma are important considerations for care for men and women experiencing gambling problems.

Abstract

Background

Men and women differ in their patterns of help-seeking for health and social problems. For people experiencing problem gambling, feelings of stigma may affect if and when they reach out for help. In this study we examine mens and womens perceptions of felt stigma in relation to help-seeking for problematic gambling.

Methods

Using concept mapping, we engaged ten men and eighteen women in group activities. We asked men and women about their perceptions of the pleasurable aspects and negative consequences of gambling; they generated a list of four hundred and sixteen statements. These statements were parsed for duplication and for relevance to the study focal question and reduced to seventy-three statements by the research team. We then asked participants to rate their perceptions of how much felt stigma (negative impact on ones own or familys reputation) interfered with help-seeking for gambling. We analyzed the data using a gender lens.

Findings

Men and women felt that shame associated with gambling-related financial difficulties was detrimental to help-seeking. For men, the addictive qualities of and emotional responses to gambling were perceived as stigma-related barriers to help-seeking. For women, being seduced by the ‘bells and whistles’ of the gambling venue, their denial of their addiction, their belief in luck and that the casino can be beat, and the shame of being dishonest were perceived as barriers to help-seeking.

Conclusions

Efforts to engage people who face gambling problems need to consider gendered perceptions of what is viewed as stigmatizing.

Keywords

Problem gambling;Help-seeking;Barriers;Stigma;Gender;Concept mapping

1. Background

1.1. Gambling, stigma, and help-seeking

Like mental illness and substance use, help-seeking for problem gambling can be impeded by public stigma and discrimination (Hing et al., 2013; Hing and Nuske, 2011; Horch, 2011; Horch and Hodgins, 2008; Pulford et al., 2009 ; Suurvali et al., 2009). People with gambling disorders may fail to seek treatment because of felt stigma. For example, only 25% of people experiencing a gambling problem seek help (Suurvali, Hodgins, Toneatto, & Cunningham, 2008). The reasons that people fail to seek help are related to their sense of self and reputation. In their review, Suurvali et al. (2009) found that people want to avoid embarrassment, shame and stigma and in so doing do not reach out for help. This fear of stigma is a predictor of delayed treatment-seeking (Tavares et al., 2003). Hing and Nuske (2011), for example, discovered that patrons of gambling venues were reticent to seek help because of feelings of shame.

Stigmatization by professionals working with clients diagnosed as pathological gamblers is reinforced by the language of the medical community and the media (Grunfeld et al., 2004 ; Rockloff and Schofield, 2004). Many providers endorse popular stereotypes of pathological gambling that create a picture of the ‘gambler’ as unable to control him/herself, irresponsible, and as liars and criminals (Grunfeld et al., 2004 ; Rockloff and Schofield, 2004). Such labeling breeds stigma and can stand in the way of a person seeking help especially if problem gambling is viewed as socially unacceptable and an activity shrouded in secrecy and shame. This is compounded by the fact that people who engage in problem gambling are often perceived as weak willed and irresponsible by work colleagues and family (Rosecrance, 1985).

Public stigma, when internalized by people experiencing gambling problems, is then experienced as felt stigma; the experiences of shame and embarrassment felt by an individual who holds a particular attribute or engages in a particular behavior that is deemed socially or morally unacceptable by the ‘majority’ of society (Goffman, 1959 ; Hing et al., 2013). Hing et al. (2013) argue that there has been little research on how felt stigma may impact help seeking behaviours, especially in relation to problem gambling.

1.2. Gender and help-seeking

Women are more likely to seek help for problem gambling. An Australian study found that 32% of women versus 13% of men sought treatment for gambling problems (Slutske, Blaszczynski, & Martin, 2009). Rockloff and Schofield (2004) identified several gender-based differences in willingness to seek help for problem gambling. Men are less likely to seek help because of perceived shame, embarrassment and associated stigma. Women often delay seeking help because they deny that they have a problem; they can be reticent to stop gambling because they will lose an important social network. What is missing from the literature are those forces or factors that generate feelings of shame and how these may differ by gender. For example are men more likely to feel shame or perceive that financial difficulties are shameful and delay seeking help?

Findings from qualitative studies of problem gambling suggest that stigma plays a key role in the publics perception of gamblers and that women with gambling problems are perceived more negatively than men (Grunfeld et al., 2004 ; Panel, 2003). This may explain why women who are pathological gamblers are less likely to seek or enter treatment for gambling-related problems, a situation analogous to treatment of women with alcohol problems. In the past, the stigma of being an alcoholic was sufficiently excessive that women were reluctant to seek treatment. Furthermore, when women did reach out for help they were often misdiagnosed (Sandmaier, 1980 ; Volberg, 1994). Studies suggest that those who seek help have a greater variety and intensity of psychological problems than those who do not seek help (Shaffer & Korn, 2002).

The aim of this paper is to better understand experiences of felt stigma as a barrier to help-seeking for men and women experiencing problem gambling. Understanding the factors that inhibit people from getting the help they need for problem gambling can be beneficial in our design of gender-based interventions that facilitate behavior change. We also recognize that there is a paucity of studies that explore problem gambling, help-seeking and stigma from a gendered lens (Hing et al., 2013). This paper explores the idea that felt stigma may be connected to the decisions of men and women to seek help for gambling problems. We did this by asking people – those engaged in gambling behavior, family of people engaged in such behavior and health service providers – about their perceptions of the impact of felt stigma on help-seeking for gambling problems.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

We used Concept Mapping,1 a mixed methods approach, to engage with a sample of twenty-eight individuals who were identified as appropriate candidates for the research study (Kane and Trochim, 2007 ; Trochim, 1989). Concept Mapping is a unique approach to collecting data, as not only do research participants come together as a group to respond to research questions, but they also have the opportunity during the Concept Mapping process to contribute to the analysis and interpretation of the data (O'Campo, Burke, Peak, Mcdonnell, & Gielen, 2005). Used commonly in program evaluation and public health and most recently in studies of mental health and violence (Burke et al., 2006; Johnsen et al., 2000; O’Campo et al., 2009 ; O'Campo et al., 2005), Concept Mapping is also considered to be in keeping with feminist approaches to social research as the perspectives of the participants take precedence over the interpretations of the researcher (Campbell & Salem, 1999).

Concept mapping is a participatory research method that was developed by social scientist William Trochim and has been frequently used in evaluation, education and organizational planning. According to Trochim (2006): “Concept mapping is a structured process, focused on a topic or construct of interest, involving input from one or more participants, that produces an interpretable, pictorial view (concept map) of their ideas and concepts and how they are interrelated.” In essence it is a method that encompasses integrated Knowledge Translation practices (CIHR, 2012), such that participants and researchers work together to create, analyse and interpret knowledge. Concept Mapping uses a staged approach to collect and collate data. In our case, participants came together as a group to brainstorm answers to a focal question, participants and researchers reviewed the final list of items (parsed for duplicates by the research team), participants sorted the items into piles of similar items and provided names for each group of items. These data were input into the software to facilitate the co-development of concept maps. Finally, participants rated each item according to rating questions specific to help-seeking in the context of stigma. The Concept Mapping software allows researchers to input data on site with participants to enable co-interpretation of the data (e.g., co-creation of the concept maps). The study team was particularly intent on obtaining an in-depth understanding of the research participants' negative and positive perceptions of gambling and how felt stigma might impact their willingness to seek help for gambling problems. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of St. Michaels Hospital and all participants gave written and informed consent.

2.2. Participants

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants who reflected: people who engaged in gambling as a leisure activity and those for whom gambling was problematic, family members of people experiencing gambling problems, and health care providers who deliver gambling treatment. Purposive sampling is the “deliberate choice of an informant based on the qualities the informant possesses” (Tongco, 2007). Purposive sampling allows the researcher to select key informants who are particularly knowledgeable in the area that is the subject of the research and are very willing to share their knowledge (Tongco, 2007). In order to more fully understand problem gambling, it is not only important to understand the views of people experiencing gambling problems, but also the perspectives of other people whose lives are affected by someone who has a gambling problem. Consequently, it was decided that family members of people with gambling problems and health care providers would also be recruited to participate in the study. The majority of research participants were recruited by placing flyers at a gambling facility in Toronto, Ontario operated by the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation. Interested participants called the study personnel and were screened for the following criteria: over the age of eighteen, had themselves gambled or had a family member who gambled within the last twelve months, had good oral and written English language skills and were able to attend two group activities held on different dates. Health care professionals were recruited for the study through research staff members who had worked with those individuals in the past.

2.3. Materials

During the screening process, individuals (other than health care providers) were screened for problems using the South Oaks Gambling Screen Short Form (SOGS-SF) (Strong, Breen, Lesieur, & Lejuez, 2003). The SOGS-SF is a reliable and valid instrument that can quickly determine if an individual is experiencing pathological gambling (Lesieur and Blume, 1987 ; Strong et al., 2003).

Of the sixty-one people who completed the screening process, twenty-eight individuals (ten males and eighteen females of which four were health care providers) met the study eligibility criteria. There were various reasons for the negative screens for the study: the location of the group sessions was too far away; participants did not speak English well and translators were not available; dates of the group sessions were not convenient or the participant was not able to attend all group sessions; participants who initially expressed interest and who were offered the opportunity to participate never got back to the research team; participants were not within the eligible ages of 19 and 64; finally, some experienced challenges answering the screening questions and thus would not be able to complete the concept mapping tasks. Based on the SOGS-SF, ten of the participants did not have gambling problems, nine were at risk for gambling problems, and nine were at risk of problem/pathological gambling.

2.4. Procedures

Participants were first asked to engage in a brainstorming activity. We held four brainstorming sessions for four groups of participants: males who gambled; females who gambled; health care providers; and those who had family members who gambled. During brainstorming, participants were asked to generate statements that described the pleasurable aspects and negative consequences of gambling. To ensure everyone understood the concept of gambling we discussed and agreed upon a definition of gambling prior to brainstorming:

Gambling can be described as betting money or something of material value on an event with an uncertain outcome, in hopes to win more money or material goods, like trips. There are a variety of activities that may be considered gambling such as, playing card games like blackjack or playing the slot machines at casinos, placing bets on horses/dogs at a race track. There are less obvious forms of gambling such as playing the lottery, betting money at a bingo hall, placing money in the stock market, online betting and playing cards with friends.

We initiated brainstorming by asking participants the following question: “Gambling is a popular passion and people have many experiences with gambling. Please generate statements that describe the pleasurable aspects and negative consequences of gambling.” Participants generated a list of four hundred and sixteen statements across the four brainstorming groups. Five team members reviewed the statement list and reduced it to seventy-three statements by removing duplicates and those that did not specifically address the focal questions.

We then asked twenty of the original twenty-eight participants to return for a sorting and rating activity, nineteen of which arrived on time and participated in the session. Eight of the original participants were not invited back to the more difficult sorting and rating sessions as they had difficulties completing the less challenging brainstorming sessions. Overall, the sorting and rating exercise consisted of three groups made up of seven men, nine women and three family members. Service providers did not participate in the sorting and rating exercise. Prior to the sorting exercise, the facilitator explained how the list of four hundred and sixteen statements was reduced to seventy-three and how to complete the sorting activity. For the sorting activity participants received individual packs of seventy-three printed cards with one statement per card. Each participant individually reviewed the statements, sorted them into piles having similar meanings, and created a name for each pile. This data was entered into the Concept Mapping software. Using multidimensional scaling, the sorted data was translated into simple point maps where each statement was reflected as a point on the map. The proximity of points on the map reflected how the participants sorted the statement into piles — closer points reflect the fact that more people sorted those statements into similar piles.

For the rating activity, participants were asked to rate, on a five point scale (one = does not interfere; five = completely interferes), whether each of the seventy-three statements interfered with help-seeking because of felt stigma (negatively impact ones reputation or familys reputation). Reputation reflects a set of beliefs and ideas about the status of a person or a group of people (Bromley, 1993 ; Kewell, 2007). People may feel that they fail to meet social expectations because they are unable to control their own behaviour (i.e., gambling) and this can lead to feelings of shame, embarrassment and guilt (Goffman, 1959). In this study we asked participants to think about how they would feel about seeking help when it might have a negative impact on their reputation (felt stigma).

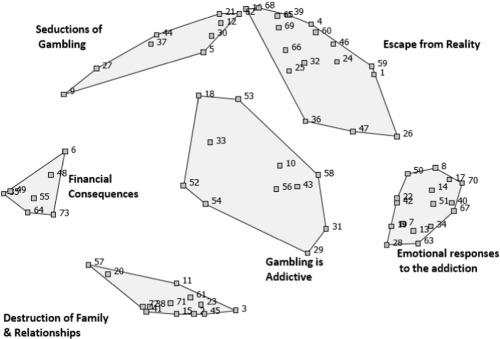

Participants were engaged in the interpretation and analyses of maps constructed during the concept mapping groups. Hierarchical cluster analysis was used to create a separate map for men and women and a single cluster map for men and women combined. The participants collectively determined which cluster solution (the total number of clusters) best reflected their ideas about gambling. Both men and women selected a six cluster solution. This mapping process with two groups – one with male participants and the other with female participants – provided gender-specific representations of the concept map. The researchers further processed the data to generate a single concept map for the entire sample. The stress value was 0.25 for the researcher-generated map; a lower value reflects acceptable goodness of fit (Kane and Trochim, 2007 ; Kruskal and Wish, 1978). We briefly present the separate gender-based concept maps followed by an analysis of the rating data.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic data

Out of the twenty-eight individuals that participated in the study, ten were males and eighteen were females. The mean age of the participants was fifty-three years 61% of the participants were born outside Canada; 32% reported their ethnic identity as Chinese and 25% reported being North American. The majority of participants were widowed, separated or divorced (39.3%) and had no children (82.1%). Almost 43% had completed post-secondary education and the majority of participants (53.6%) earned less than forty thousand dollars per year. Based on responses to the SOGS-SF, 36% were non-problem gamblers, 32% had potential to be or were likely problem gamblers, 3.6% were likely to have problems with gambling and 28.6% were likely to have significant or severe problems. An analysis of the data collected for females using the SOGS-SF shows that 38% of the female participants had no problems gambling, 28% had potential for problems, 0% were classified as likely to have problems with gambling and 33.4% had significant or severe gambling problems. Furthermore, the results of the data collected from males using the SOGS-SF showed that 30% had no gambling problems, 40% were likely to have problems with gambling, 10% were likely to have gambling problems and 20% had significant or severe problems.

3.2. Gender-based Concept Maps

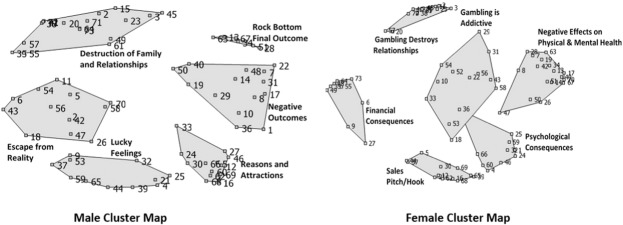

Fig. 1 shows the concept maps that were developed independently by men and women during their separate group activities. The male map is on the left with the female map on the right. Men and women described the concepts underlying the statements in different terms. For example, men named one cluster rock bottom final outcome, which included statements such as feelings of shame, anxiety and depression. The cluster named negative effect on physical and mental health developed by women included similar statements such as anxiety and feelings of being isolated. While it is useful to see how men and women differentially named their clusters, for a more nuanced interpretation of gender differences the research team generated a 6-cluster map solution with men and women combined using all of the sorting data. By combining the sorting and rating data the research team was able to compare male and female ratings on stigma and help-seeking. The 6-cluster map that is the compilation of mens and womens sorting activities is shown in Fig. 2.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. Cluster maps by gender. |

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Researcher generated cluster map. |

3.3. Rating results

When rating the seventy-three statements we asked participants to reflect on how felt stigma (damage to their reputation or to the reputation of their family) might influence the decision to seek help for problem gambling. Participants rated the seventy-three statements on a scale of one to five with one a reflection that the statement does not interfere with help-seeking and with five reflecting that the statement almost/completely interferes with help-seeking. In Table 1 we list the clusters with their respective statements and the statement ratings (low, moderate, high) by gender. Using the distribution of the ratings separately for men and women, we used the twenty-fifth (3.36 women; 3.14 men) and seventy-fifth percentiles (women: 3.91; men 4.00) to create categories of “high”, “moderate”, and “low.” Men perceived that financial consequences of gambling created stigma and acted as barriers to help-seeking, endorsing all seven statements as high in that cluster. Women endorsed four (6, 35, 49, 64) of the statements in this cluster.

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Financial consequences | ||

| Continue to gamble to cover losses (6) | High | High |

| Use money from your own business/disability money to gamble (35) | High | High |

| Job loss (48) | High | Moderate |

| Financial ruin (49) | High | High |

| Debt/financial losses/bankruptcy (55) | High | Moderate |

| Embezzle money from your employer (64) | High | High |

| Stealing (73) | High | Moderate |

| Escape from reality | ||

| Feels good like drugs and alcohol (1) | Low | Moderate |

| Feel lucky (4) | Low | High |

| Receive VIP treatment (16) | Low | Moderate |

| Gambling reduces stress (24) | Low | Moderate |

| Casino tricks you into thinking you can win (25) | Low | Moderate |

| People use excuses or illogical reasons to gamble (26) | High | Moderate |

| Hypnotic/lose sense of time (no clocks on floor, lots of noise/lights/colour) (32) | Low | Moderate |

| Perception that the games are rigged (36) | Low | Low |

| Fun (39) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Can forget worries and find peace (46) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Constant highs and lows (47) | High | Moderate |

| Physiologically arousing (59) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gambling relieves boredom (60) | Low | Moderate |

| Thrilling to win (65) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gambling is an escape from reality (66) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Entertaining (68) | Low | High |

| No language barrier (69) | Low | Low |

| Seductions of gambling | ||

| Believe the casino can be beat (5) | Low | High |

| Can help resolve your financial problems (9) | High | High |

| Casinos make you feel important when you spend lots of money (12) | Low | Moderate |

| Casino is an uplifting environment (21) | Low | Moderate |

| Acquire large sums of money quickly (27) | High | High |

| Gambling is a way to kill time (30) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Can meet people but do not have to develop relationship (37) | Low | Low |

| Meet people/friends (44) | Low | Moderate |

| Enjoy perks of casinos (e.g. good food, free shows, alcohol, open long hours, incentives to play, easy access) (62) | Moderate | High |

| Gambling is addictive | ||

| Gambling is a worse addiction (e.g. don't get sick like with drugs and alcohol) (10) | High | Moderate |

| Use gambling as a ways to cope (18) | High | Low |

| Blame others for losing (29) | Moderate | Low |

| Blame ourselves for the loss (31) | Low | Moderate |

| Binge gambling (33) | High | Moderate |

| Can't stop even if you want to (43) | High | Moderate |

| Can't accept losses (52) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Get a gut feeling if you will win or lose (53) | High | High |

| Gambling takes over your life (54) | High | High |

| Don't want to admit you are addicted (56) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gambling is always on your mind (constant thought of it) (58) | High | Moderate |

| Emotional responses to the addiction | ||

| Feel isolated (7) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Gambling increases alcohol and drug use (8) | Low | Moderate |

| Lose self-respect/self-esteem (13) | High | Moderate |

| Frustrated when losing (14) | High | Low |

| Get physical pain when your lose (feel sick) (17) | Moderate | Low |

| Sense of failure (19) | High | Moderate |

| Gambling is like alcoholism (22) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Shame (28) | High | Moderate |

| Can lead to desperation (34) | High | Moderate |

| Gambling leads to anger at self (40) | Moderate | Low |

| Deep down people don't feel good about themselves (42) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Will go insane if you stop gambling (50) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Anxiety (51) | High | Moderate |

| Gambling can lead to suicide (63) | High | Moderate |

| Depression (67) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Physiologically and mentally exhausting (70) | Moderate | Low |

| Destruction of family and relationships | ||

| The severity of the problem is a shock for families (2) | High | Low |

| Creates rifts/conflicts in relationships (3) | High | Moderate |

| Feel pressure from spouse/friends to gamble (11) | Low | Moderate |

| Loss of trust of family members (15) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Use money meant for family (20) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Anger from families (23) | High | Moderate |

| Emotional neglect of children (38) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Material neglect of children (41) | Low | Moderate |

| Destroys relationships/marriages (45) | High | Moderate |

| Dishonesty (e.g. lie to family, at work, etc.) (57) | High | High |

| Lose friendships (61) | Moderate | Low |

| Hide the problem from family (71) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Children may be apprehended due to parental gambling (72) | Low | Moderate |

Note: Bracketed numbers represent statement numbers from 1 to 73.

Men endorsed two statements as barriers to help-seeking in the escape from reality cluster — people use excuses or illogical reasons to gamble (26) and forget worries and find peace (46). Women perceived that feeling lucky and the entertaining nature of gambling would be stigma-related barriers to help-seeking. Women perceived the seductions of gambling were barriers to help-seeking; believing the casino can be beat (5), you can meet people/friends through gambling activities (44), that gambling can solve financial problems (9) discouraged help-seeking. For example, having to admit to others that she was isolated and started to gamble as a way to connect with others was perceived as embarrassing and thus a barrier to reach out for help. During the group activities women talked a lot about the perks (62) that casinos give patrons (e.g., food, free shows, VIP status for those who played often, socializing with others with a common interest). While they enjoyed these perks their ratings suggest that they felt that having to admit that gambling got out of control, because they were enticed by these perks, would be stigmatizing. For men, having to accept and/or admit to others that you succumbed to the addiction (10) and that it was taking over your life (54) were perceived as stigma-related barriers that would deter someone from seeking help.

Within the gambling is addictive cluster men felt that gambling, as an addiction, was worse than substance use (10) because there were no external symptoms (e.g., sickness with alcohol or drug use) and this might be problematic for help-seeking. In addition, men felt that if gambling was used as a coping mechanism (18) then it might be difficult to reach out for help. Being unable to control your gambling (33, 43, 53, 54, and 58) was identified as a stigma-related barrier to self-care. Women endorsed two statements related to inability to control gambling as deterrents to help-seeking (53, 54).

Men endorsed seven of sixteen statements as stigma-related barriers to help-seeking in the emotional responses to gambling cluster. Many of these statements related to self-perceptions such as loss of self-respect (13), the frustration they felt when losing (14), sense of personal failure (19), feelings of shame (28) and desperation (34), and emotional distress such as anxiety (51) and suicide (63). The women did not rate any of the statements in this cluster as highly problematic for help-seeking. Within the cluster, destruction of family and relationships, men endorsed five items as stigma-related barriers to help-seeking — family shock at the severity of the problem (2), relationship rifts/conflicts (3), family anger (23) and destruction of relationship/marriages (45) and dishonesty (57). These items reflect the shame of knowing that a problem behavior has destroyed family/relationship connections. Among women, dishonesty (57) was the only statement endorsed as stigma-related barrier in this cluster.

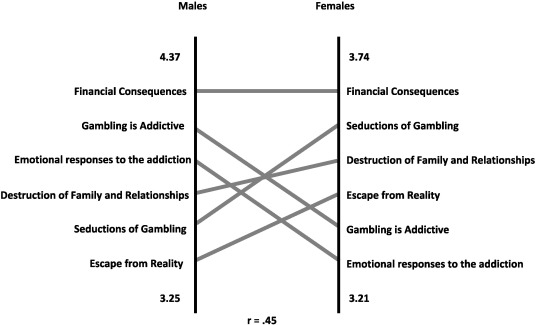

3.4. Pattern matches

To further understand the ratings we generated a pattern match graph. Fig. 3 shows the average rating for each cluster for the researcher-generated map. This also allowed us to examine the strength of the correlation between male and female perceptions of stigma-related barriers to help-seeking. Both men and women ranked financial consequences of gambling as the most important stigma-related barrier to help-seeking. While gambling is addictive was ranked second most important for men, it was ranked as the fifth most important by women. Interestingly, while men ranked the emotional responses to the addiction as the third most important stigma-related barrier to help-seeking, this was ranked last by women. The seductions of gambling cluster was ranked second by women and fourth by men. These differences in ranking for men and women are not unexpected given the correlation between the clusters for men and women was moderate (r = 0.5).

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Pattern match of stigma-related barriers to help-seeking by gender. |

4. Discussion

This study used concept mapping as a way to understand gendered perceptions of felt stigma in relation to help-seeking behavior for gambling problems. Both men and women felt that the associated shame of financial difficulties that develop from gambling problems was detrimental to help-seeking. For men, the addictive qualities of and emotional responses to gambling were the next most salient barriers to help-seeking when they were considering felt stigma. For example having to admit (to self or others) that gambling had taken over ones life or that you were using it to cope; the feelings of shame, the loss of self-respect and sense of failure and distress (anxiety and suicide) that go along with gambling and the breakdown of relationships were perceived by men to be stigmatizing and a deterrent to help-seeking. For women, admitting that you were seduced by the ‘bells and whistles’ of the gambling venue where they felt important, their denial of their addiction, their belief in luck and that the casino can be beat, and the shame of being dishonest were perceived as barriers to help-seeking.

We often think in terms of women internalizing distress which is then manifested in depression and/or anxiety. The men in this sample identified emotional concerns that they perceived to be stigmatizing and would discourage someone from reaching out for help. Women did not focus so much on emotional concerns but on the seductive nature of the gambling environment and irrational beliefs such as the casino can be beat or had a feeling you were going to be lucky. For both men and women, having to admit to these irrational or distressful beliefs and emotions, either to self or to others, might prove to be barriers to help-seeking. It may not be surprising, then, that men felt that there would be shame associated with admitting emotional vulnerability (e.g., using gambling to cope), while women might feel shame admitting that they were seduced by the casino environment and such irrational beliefs that the casino can be beat. Our findings are in line with those of Rockloff and Schofield (2004) who found that men, more than women, felt that feelings such as shame and embarrassment of the addiction would prevent individuals from getting the help that they needed. Consistent with previous literature, women in this study perceived that gamblers may not seek help because of denial and reluctance to change their lifestyle out of fear of losing their social networks (Rockloff and Schofield, 2004; Suurvali et al., 2012 ; Suurvali et al., 2009).

Research by Horch and Hodgins (2008) showed that people want social distance from people they perceive as having a gambling problem and this is particularly true when the gambler is male. If shame and embarrassment over their addiction stands in the way of getting help, there is a role for public education approaches to address the negative perceptions of people who experience gambling problems in the community and reduce the stigma they face. Further research is needed to understand what factors are most influential in the decision-making process of individuals who overcome barriers and seek treatment for problem gambling.

Our study seems to suggest that men and women may have different visions of self in relation to problem gambling or at least there are particular behaviors/beliefs/feelings that they perceive might be particularly difficult to admit to or share with others; yet sharing these vulnerabilities is a necessary step in the journey to recovery. Men were concerned with the stigma of emotional responses to gambling and mental health concerns in relation to help-seeking, while women perceived gambling to be an attractive lifestyle and this was perceived as a deterrent to help-seeking. It is possible that male and female perceptions of damage to reputation lie along different conceptual domains. More research to understand how male and female perceptions of self are intertwined with motivations for gambling might move us closer to understanding how identity, shame and management of the public self may play a role in whether people reach out for help or continue to suffer. For example, some suggest that women regard gambling as a liberating experience; one that provides an opportunity to escape worries and stress. This seems reflective of the perceptions of women in our study (Hallebone, 1997; Johnson and McLure, 1997 ; Thomas, 1995).

A strength of this study is the richness of the information that was collected on perceptions of barriers to help-seeking as well as the ability of the data to delineate male–female differences in this regard. A potential constraint of the small sample size and use of a purposive sampling method is that we cannot generalize to the larger population of people who may experience gambling problems, but this was not the intent. Our goal was to focus on information rich cases that would provide in-depth insight into gambling behaviors, particularly perceptions of gambling among people who were in some way engaged in gambling culture, directly or indirectly. The cluster domains generated might have differed with a more representative sample of people who engage in social gambling or experience gambling problems. For example, the older mean age of our participants may have influenced the types of items generated in response to the focal topic and the cluster solutions; future research in this area would benefit from exploring issues of stigma and help-seeking among different age groups. Youth, for example, may experience stigma differently than seniors. Furthermore, we recruited participants from a single urban site and a single gambling venue so we may have missed people from suburban and rural areas of Ontario; a consideration for future studies.

In considering the implications that the findings of this study have for practice, it is clear that efforts to engage people who gamble in treatment need to consider the differences in how men and women experience problem gambling and associated stigma. Peer outreach and support is a possible approach to engage male problem gamblers in treatment as people with lived experience may be able to break through the stigma and establish a connection with men who are experiencing problem gambling and facilitate engagement in treatment that will help them cope with mental health concerns. Gomes and Pascual-Leone (2009) discovered that people involved in the self-help/mutual aid group Gamblers Anonymous (GA) were much more likely to be ready to change their gambling behaviours and more open to seeking professional help than people who were not involved in GA. People who received treatment for problem gambling and had prior GA involvement were more likely to be successful than people who did not attend GA (Petry, 2003). GA may create greater personal awareness of the harms associated with problem gambling. In addition to providing social support, peers in the GA self-help model take on an educational role which helps people experiencing gambling problems overcome felt stigma and seek treatment for their concerns.

A peer outreach strategy for women may be particularly useful to help them understand how the negative consequences of gambling can outweigh their positive experiences. This strategy could include a peer support model that encourages women to participate in more prosocial activities that provide the same pleasurable feelings as gambling and that provides alternative avenues for social engagement. For example Bulcke (2008) found that women feel lonely without gambling in their life. Research suggests that women who attended GA established informal networks with other women in the mutual support group and maintained these relationships outside the GA environment (Laracy, 2011).

Role of funding sources

This research was supported by a grant from the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors

Baxter: drafting of manuscript, manuscript revisions, approval of final version.

Salmon: data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript revisions, approval of final manuscript.

Carasco-Lee: participant recruitment, data collection.

Dufresne: drafting the manuscript, manuscript revisions, approval of final manuscript.

Matheson: study concept, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, manuscript revisions, approval of final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to you, our participants, who willingly gave a considerable amount of time and energy to the group activities. The project and this report would not have been possible without you and your insights into gambling.

References

- Bromley, 1993 D.B. Bromley; Reputation, Image and Impression Management; John Wiley & Sons, Oxford, England (1993)

- Bulcke, 2008 G.M. Bulcke; Identifying barriers to treatment among women gamblers; Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 69 (2-A) (2008), p. 751

- Burke et al., 2006 J.G. Burke, P. O'Campo, G.L. Peak; Neighborhood influences and intimate partner violence: Does geographic setting matter?; Journal of Urban Health, 83 (2) (2006), pp. 182–194

- Campbell and Salem, 1999 R. Campbell, D.A. Salem; Concept mapping as a feminist research method: Examining the community response to rape; Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23 (1) (1999), pp. 65–89

- CIHR, 2012 CIHR; Guide to Knowledge Translation Planning at CIHR: Integrated and End-of-Grant Approaches; Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Ottawa, Ontario (2012)

- Goffman, 1959 E. Goffman; The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Doubleday, New York (1959)

- Gomes and Pascual-Leone, 2009 K. Gomes, A. Pascual-Leone; Primed for change: Facilitating factors in problem gambling treatment; Journal of Gambling Studies, 25 (1) (2009), pp. 1–17

- Grunfeld et al., 2004 R. Grunfeld, M. Zangeneh, A. Grunfeld; Stigmatization dialogue: Deconstruction and content analysis; International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1 (2) (2004), pp. 1–14

- Hallebone, 1997 E.L. Hallebone; Saturday night at the Melbourne Casino; Australian Journal of Social Issues, 32 (4) (1997), pp. 365–390

- Hing et al., 2013 N. Hing, L. Holdsworth, M. Tiyce, H. Breen; Stigma and problem gambling: Current knowledge and future research directions; International Gambling Studies, 14 (1) (2013), pp. 64–81 http://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2013.841722

- Hing and Nuske, 2011 N. Hing, E. Nuske; Assisting problem gamblers in the gaming venue: a counsellor perspective; International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9 (6) (2011), pp. 696–708

- Horch, 2011 Horch, J. D. (2011). Problem gambling stigma: Stereotypes, labels, self-stigma, and treatment-seeking. (Dissertation).

- Horch and Hodgins, 2008 J.D. Horch, D.C. Hodgins; Public stigma of disordered gambling: Social distance, dangerousness, and familiarity; Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27 (5) (2008), pp. 505–528

- Johnsen et al., 2000 J.A. Johnsen, D.E. Biegel, R. Shafran; Concept mapping in mental health: Uses and adaptations; Evaluation and Program Planning, 23 (1) (2000), pp. 67–75

- Johnson and McLure, 1997 K. Johnson, S. McLure; Women and gambling: A progress report on research in the western region of Melbourne; Paper presented at the Responsible Gambling: A Future Winner, Proceedings of the 8th National Association for Gambling Studies, Melbourne, Australia (1997)

- Kane and Trochim, 2007 M. Kane, W.M.K. Trochim; Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation; Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA (2007)

- Kewell, 2007 B. Kewell; Linking risk and reputation: A research agenda and methodological analysis; Risk Management, 9 (4) (2007), pp. 238–254

- Kruskal and Wish, 1978 J.B. Kruskal, M. Wish; Multidimensional Scaling; M. Wish (Ed.)Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, Calif. (1978)

- Laracy, 2011 A.J. Laracy; The Promise of Another Spin: Identity and Stigma Among Video Lottery Players in St. Johns, Newfoundland and Labrador; (AAIMR88011), Memorial University of Newfoundland (2011)

- Lesieur and Blume, 1987 H.R. Lesieur, S.B. Blume; The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers; The American Journal of Psychiatry, 144 (9) (1987), pp. 1184–1188

- O’Campo et al., 2009 P. O’Campo, C. Salmon, J. Burke; Neighbourhoods and mental well-being: What are the pathways?; Health & Place, 15 (1) (2009), pp. 56–68 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.004

- O'Campo et al., 2005 P. O'Campo, J. Burke, G.L. Peak, K.A. Mcdonnell, A.C. Gielen; Uncovering neighbourhood influences on intimate partner violence using concept mapping; Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59 (7) (2005), pp. 603–608

- Panel, 2003 G.R. Panel; Stage One Report: The Experiences of Problem Gamblers, Their Families and Service Providers; (2003) (Retrieved from Victoria, Australia)

- Petry, 2003 N.M. Petry; Patterns and correlates of gamblers anonymous attendance in pathological gamblers seeking professional treatment; Addictive Behaviors, 28 (6) (2003), pp. 1049–1062

- Pulford et al., 2009 J. Pulford, M. Bellringer, M. Abbott, D. Clarke, D. Hodgins, J. Williams; Barriers to help-seeking for a gambling problem: The experiences of gamblers who have sought specialist assistance and the perceptions of those who have not; Journal of Gambling Studies, 25 (1) (2009), pp. 33–48

- Rockloff and Schofield, 2004 M.J. Rockloff, G. Schofield; Factor analysis of barriers to treatment for problem gambling; Journal of Gambling Studies, 20 (2) (2004), pp. 121–126

- Rosecrance, 1985 J. Rosecrance; Compulsive Gambling and the medicalization of deviance; Social Problems, 32 (3) (1985), pp. 275–284

- Sandmaier, 1980 M. Sandmaier; Alcoholics Invisible: The ordeal of the female alcoholic; Social Policy, 10 (1980), pp. 25–30

- Shaffer and Korn, 2002 H.J. Shaffer, D.A. Korn; Gambling and related mental disorders: A public health analysis; Annual Review of Public Health, 23 (1) (2002), pp. 171–212

- Slutske et al., 2009 W.S. Slutske, A. Blaszczynski, N.G. Martin; Sex differences in the rates of recovery, treatment-seeking, and natural recovery in pathological gambling: Results from an Australian community-based twin survey; Twin research and human genetics: the official journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 12 (5) (2009), p. 425

- Strong et al., 2003 D.R. Strong, R.B. Breen, H.R. Lesieur, C.W. Lejuez; Using the Rasch model to evaluate the South Oaks Gambling Screen for use with nonpathological gamblers; Addictive Behaviors, 28 (8) (2003), pp. 1465–1472

- Suurvali et al., 2009 H. Suurvali, J. Cordingley, D. Hodgins, J. Cunningham; Barriers to seeking help for gambling problems: A review of the empirical literature; Journal of Gambling Studies, 25 (3) (2009), pp. 407–424

- Suurvali et al., 2008 H. Suurvali, D. Hodgins, T. Toneatto, J. Cunningham; Treatment seeking among Ontario problem gamblers: Results of a population survey; Psychiatric Services, 59 (11) (2008), pp. 1343–1346

- Suurvali et al., 2012 H. Suurvali, D.C. Hodgins, T. Toneatto, J.A. Cunningham; Hesitation to seek gambling-related treatment among Ontario problem gamblers; Journal of Addiction Medicine, 6 (1) (2012), p. 39

- Tavares et al., 2003 H. Tavares, S.S. Martins, D.S.S. Lobo, C.M. Silveira, V. Gentil, D.C. Hodgins; Factors at play in faster progression for female pathological gamblers: An exploratory analysis; Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64 (4) (2003), pp. 433–438

- Thomas, 1995 S. Thomas; More than a flutter: Women and problem gambling; Paper Presented at the High Stakes in the Nineties, Sixth National Conference of the National Association for Gambling Studies, Fremantle, Australia (1995)

- Tongco, 2007 M.D.C. Tongco; Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection; Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 5 (2007), p. 147

- Trochim, 1989 W.M.K. Trochim; Concept Mapping: Soft science or hard art?; Evaluation and Program Planning, 12 (1) (1989), pp. 87–110

- Trochim, 2006 W.K. Trochim; Retrieved October 4th, 2015 from http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/conmap.php (2006)

- Volberg, 1994 R.A. Volberg; The prevalence and demographics of pathological gamblers: Implications for public health; American Journal of Public Health, 84 (2) (1994), pp. 237–241

Notes

1. Concept Systems. The Concept System. Ithaca, NY: Concept Systems Inc.; 2004.http://www.conceptsystems.com.http://www.conceptsystems.com.

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?