Abstract

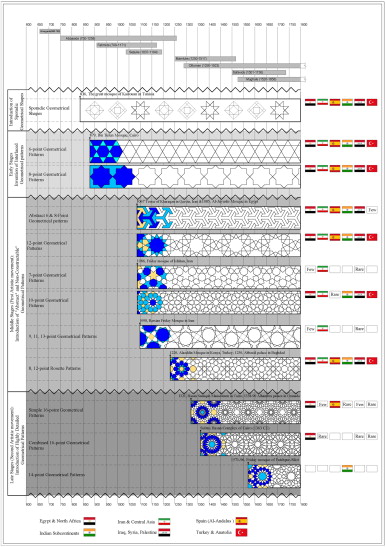

This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century.

Keywords

Islamic geometrical patterns ; Islamic art ; Islamic architecture ; History of Islamic architecture ; History of architecture

1. Introduction

For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads to inappropriate use in terms of time scale accuracy and architectural style matching.

This study investigates IGPs under historical and regional perspectives to elucidate the issues related to their suitability and appropriate use as decorative elements for buildings. The three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout the history of Islamic architecture is also presented.

2. Method

This research is based on descriptive approaches, for which our goals were to collect data on surviving geometrical patterns and classify them on the basis of time scale and regionalism. Such approaches provide dialectic answers to a wide range of philosophical and architectural questions, such as when or where a particular pattern was extensively used. The literature review presents a selected collection of 100 well-known surviving buildings from West Africa to the Indian subcontinent; the collection historically spans nearly 12 centuries, dating back to the early stages of Islam up to the 18th century. It covers the most important classic architectural treasures of the Islamic world. For this reason, this study comprehensively referred to not only encyclopedias on architectural history, but also regional/local architectural studies.

3. When and how did geometry penetrate Islamic architecture?

The expansion and development of geometry through Islamic art and architecture can be related to the significant growth of science and technology in the Middle East, Iran, and Central Asia during the 8th and 9th centuries; such progress was prompted by translations of ancient texts from languages such as Greek and Sanskrit (Turner, 1997 ). By the 10th century, original Muslim contributions to science became significant. The earliest written document on geometry in the Islamic history of science is that authored by Khwarizmi in the early 9th century (Mohamed, 2000 ). Thus, history of Islamic geometrical ornaments is characterized by a gap of nearly three centuries—from the rise of Islam in the early 7th century to the late 9th century, when the earliest example of geometrical decorations can be traced from the surviving buildings of the Muslim world (Table 1 ).

4. Types of Islamic geometrical patterns

The definitions and classifications of IGPs are beyond the scope of this article, but a brief description of IGP types is provided.

For centuries, the compass and straight edge were the only tools used to construct polygons and required angles. Therefore, all IGPs originate from the harmonious subdivisions of circles and are based on templates of circle grids. Some researchers stated that the use of the circle is a way of expressing the Unity of Islam (Critchlow, 1976 ; Akkach, 2005 ). According to this doctrine, the circle and its center is the point at which all Islamic patterns begin; the circle is a symbol of a religion that emphasizes One God and the role of Mecca, which is the center of Islam toward which all Moslems face in prayer.

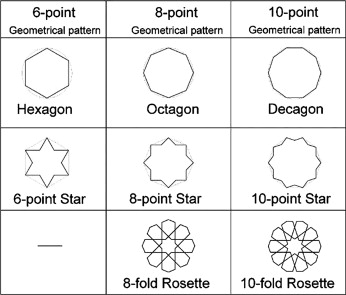

Most IGPs are based on constructive polygons, such as the hexagon and octagon. Star polygons, which are fundamental elements of IGPs, are created by connecting the vertices of constructive polygons. From this category emerged the first level of IGP classification (El-Said et al ., 1993 ; Broug, 2008 ). For instance, all patterns whose main elements are from a hexagon or a hexagram are classified as 6-point geometrical patterns; a star is called a 6-point star (Fig. 1 ). Accordingly, patterns are labeled as 8-, 10-, 12-…point geometrical patterns. Fig. 1 shows that at a certain level, the sides of the two adjacent rays of the 6-point star become parallel or divergent, thereby creating a deformed hexagon (i.e., rosette petals). Interestingly, the evolution of IGPs follows a difficult path of construction, in which polygons are built from the most easily formed shape (i.e., hexagon) to more complicated polygons and stars.

|

|

|

Fig. 1. First level of IGP classification. |

4.1. Umayyad architecture (660–750 CE)

By the end of the 7th and early 8th centuries, vegetal and floral patterns derived from Sassanid and Byzantine architecture became common in Islamic architecture. A popular surviving building from this period is the Dome of Rock , which was built in 688–691 CE (Grube and Michell, 1995 ). This structure is lavishly decorated with vegetal and geometrical motifs, but most of its ornaments—geometrical motifs in particular—are later additions and are not classified as products of the Umayyad era.

In 705 CE, substantial parts of the Damascus Christian Temple were converted into the Great Mosque of Damascus (Flood, 2001 ). The original decorative patterns were floral, resembling the rich gardens and natural landscape of Damascus. The floor finishing of the courtyard was repaired and refurbished a number of times; its geometrical designs are therefore also later additions and not original. The finishing surfaces and facades of Umayyad buildings are mostly molded stucco, mosaic, and wall paintings, with figural and floral motifs. By the end of the Umayyad era, however, the use of figural patterns in mosques became limited. Our survey shows no sign of the use of geometrical motifs, but vegetal ornaments remain common features of Umayyad architecture.

4.2. Abbasids architecture (750–1258 CE)

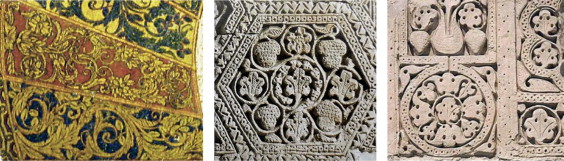

The Great Mosque of Kairouan (Tunisia), originally constructed in 670 CE and rebuilt in 836 CE, is an excellent example of Abbasid-Aghlabid buildings. The ornaments on this building are designed primarily with vegetal and floral motifs, but some elementary geometrical shapes are also observed. These solitary geometrical shapes (Fig. 2 ) are among the earliest attempts to apply geometrical ornaments in Islamic architecture.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. The Great Mosque of Kairouan; basic geometrical shapes of interior decoration. |

The simple 6- and 8-point geometrical patterns used in the Mosque of Ibn-Tulun (876–879 CE) are among the earliest examples of woven geometrical patterns in Muslim decorative arts (Fig. 3 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 3. Mihrab of Great Mosque of Cordoba (left) and 9th century carved stucco from Samarra in Iraq. |

The Mosque of Ibn-Tulun is considered a milestone in terms of its introduction of geometrical patterns to Islamic architecture. By the end of the 9th century, geometrical motifs received a warm welcome from Muslim architects and artisans. The extensive influence of geometry considerably affected other aspects of Islamic architecture. For example, the transformation from the naturalism of early Islamic ornaments to new levels of abstraction was an immediate effect of geometry on floral ornaments. Samarra vegetal motifs are the products of this era, during which application shifted from the stem scrolling of continuously running volutes (sinusoidal growth) to circle grids and tangential circles (Fig. 3 ).

The Abbasid Palace in Baghdad (1230 CE) and the Madrasa of Mustansiriyeh (1233 CE) are adorned with Muqarnas decorations and detailed geometrical patterns of carved brickwork and terracotta. These structures are excellent representatives of the architectural traditions and techniques of the late Abbasid and early Seljuk eras. From such structures, one finds some of the earliest examples of rosette petals introduced to 8- and 12-point star patterns (Fig. 4 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Ibn-Tulun Mosque in Egypt (first two panels from left); Abbasid Palace in Baghdad (last two panels). |

Architectural decorations and ornaments, such as wall paintings, carved wood, stone, stucco, terracotta, and brickwork, became highly popular in the Abbasid era. By the late 8th and early 9th centuries, geometrical shapes were introduced to surface decoration. However, woven geometrical patterns (6- and 8-point patterns) began dominating Islamic architecture only during the late 9th century.

4.3. Fatimids architecture (909–1171 CE)

Al-Azhar Mosque (970–972 CE) was the first mosque and Madrasa to be built by the Fatimids in Cairo. Parts of the original stucco panels (with vegetal motifs) and window screens (with geometrical designs) survived. However, the stucco works above the windows and on the walls (with an abstract 6-point geometrical design) were added during the Caliph al-Hafiz (1129–1149). Another Mihrab with significant geometrical decorations was built during the Ottoman restoration in the 18th century (Behrens-Abouseif, 1992 ). The Al-Juyushi Mosque (1085 CE) in Cairo is a relatively small structure, whose most significant surviving element is the lavishly carved stucco of its Mihrab, with floral and geometrical patterns. The abstract 6-point patterns over the spandrel of the Mihrab are similar to Seljuk style. The Al-Aqmar Mosque (1125 CE) in Cairo is an outstanding example of mature Fatimid architecture. Its façade is elaborately filled with calligraphic, vegetal, and geometrical decorations. However, the motifs are a replication of previously introduced designs. Another remarkable Fatimid building is the Mosque of Al-Salih-Tala'i (1160 CE), which is closely similar to the Al-Aqmar Mosque in terms of structure and decorative techniques (Fletcher and Cruickshank, 1996 ). As with the Al-Aqmar Mosque, 6- and 8-point star shapes can be found in the form of projected sculptural decorations over the walls. A perfectly proportioned 12-point pattern is carved over the Minbar—an addition during the Mamluk era in 1300 CE. The carved wooden door, which dates back to 1303, is also decorated with 8- and 12-point geometrical rosette patterns.

Early Fatimid decorative ornaments are commonly in the form of isolated elements, rather than entire surface-covering patterns. Geometrical patterns became prevalent because of the heavy influence of Seljuk architecture in the late Fatimid era.

4.4. Seljuk architecture (1038–1194 CE): first artistic movement

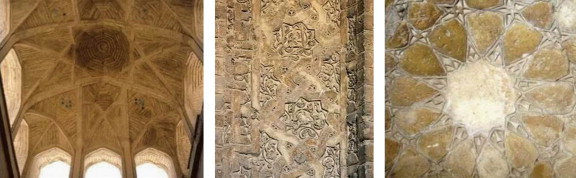

The Seljuks exerted tremendous efforts in transforming their ornaments from floral and figural into geometrical decorations, and their architecture is strongly characterized by geometrical patterns. Seljuk architects and artisans designed sophisticated patterns; abstract 6- and 8-point geometrical patterns can be observed throughout this era (Table 1 ). The abstract 6-point patterns, which are based on Tetractys motifs, were extensively used by Muslim architects in both Seljuk and late Fatimid buildings, such as the Al-Juyushi Mosque.

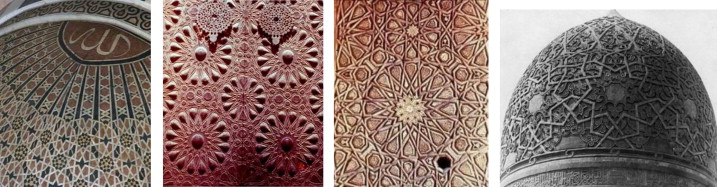

The Tomb Towers of Kharaqan (Fig. 5 ), built from 1067 to 1093 CE in the Qazvin province of Iran, are examples of early Seljuk architecture. The Towers' facades are elaborately decorated with very fine ornamental panels, each having different patterns, including stars and abstract geometrical motifs.

|

|

|

Fig. 5. Tower of Kharaqan in Qazvin, 12-point, 6-point, abstract 6-point, and 8-point geometrical patterns. |

Constructed almost at the same time as the Abbasid Palace in Baghdad, Madrasa Al-Firdaws (1236 CE) in Aleppo, Syria features a Mihrab crown over which rosette petals adorn the star patterns. The marble Mihrab is decorated with geometrical patterns that have remarkably detailed 8-point rosette arrangements. The Friday Mosque of Isfahan was developed largely during the Seljuk era. It is a perfect example of a structure adorned with detailed Seljuk decorative patterns made of brickwork (Grube and Michell, 1995 ).

Fig. 6 shows that during the late 11th and early 12th century, 5- and 8-point star concepts were frequently used in decorative elements and the techniques of integrating these decorative concepts with structural elements had already been invented. Apart from the common 6- and 8-point geometrical patterns, other amazing patterns can be found on the walls of the southern domed area, which dates back to 1086 CE. The first wall features the rarest examples of patterns containing a heptagon, and another wall is adorned with what may be one of the earliest examples of 10-point geometrical patterns.

|

|

|

Fig. 6. Great Mosque of Isfahan in Iran (left); Barsian Friday Mosque, 9- and 13-point patterns (center-left). |

Geometrical patterns were developed to a significant extent by the Seljuks. A survey of the decorative patterns of this era—from the early stages to the time at which the Friday Mosque of Isfahan was constructed—reveals an artistic movement that drove radical change in the application of conventional geometrical patterns (e.g., the introduction of highly complex and sophisticated 10-point geometrical patterns, as well as abstract 6- and 8-point geometrical patterns). This movement continued on to the Barsian Friday Mosque (1098), to the early 13th century when unique 7-, 9-, 11-, and 13-point patterns (patterns of nonconstructible polygons) were used (Fig. 6 ).

4.5. Mamluk architecture (1250–1517 CE): second artistic movement

The Mosque of Baybar (1267 CE) is one of the earliest buildings built by the Mamluks in Cairo. The only noticeable geometrical ornaments in this building are window grilles with the same 12-point patterns as those found in the Kharaqan tombs in Iran.

The Qalawun Complex in Cairo (1283–1285 CE) has attractive finishing surfaces with geometrical motifs. Its window grilles, doors, walls, and ceilings are adorned with repeated 6-, 8-, and 12-point patterns, making this monument one of the most outstanding representatives of Mamluk heritage. The mausoleums Mihrab is decorated with 10-point geometrical patterns, which may be the earliest of their type. Aside from these patterns, all the other ornaments are replicas of Seljuk and Fatimid styles.

Highly advanced 6- and 8-point geometrical patterns similar to those in the Qalawun Mosque adorn the Mosque of Al-Nasir Mohammad (1318–1334 CE). An almost identical 10-point geometrical pattern also appears in the hood of its Mihrab (Fig. 7 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 7. From left: hood of Mihrab in the Mosque of Al-Nasir Mohammad; Sultan Hassan Complex in Cairo; 16-point geometrical patterns on the entrance doors; carved wooden Minbar and dome of Qaybtay Mosque. |

The Sultan Hassan Complex (1356–1361 CE) has brilliant floral decorative patterns, but its most striking features are the most advanced types of 6-, 8-, 10-, and 12-point patterns and one of the earliest examples of 16-point patterns, found in the panels of its wooden Minbar (Fig. 7 ). Although 16-point stars adorn the dome of the Hasan Sadaqah Mausoleum (1321 CE in Cairo), the 16-point patterns in the Sultan Hassan Complex are astonishingly complex and combined with 9-, 10-, and 12-point stars and rosettes. Surprisingly, signs of a 20-point star can be found on the suspended grand bronze lantern of the sanctuary. The Sultan Hassan Complex was built during the early stages of the second artistic movement in the history of IGPs; during this period, Muslim architects and artisans began combining multiple types of patterns (such as 6-, 8-, 9-, and 10-point patterns) in a single decorative arrangement (Table 1 ).

Similar examples of 6-, 8-, 10-, 12-, and 16-point patterns characterize the decorative elements of the Khanqah of Sultan Faraj-Ibn-Barquq (1399–1411 CE) and the Muayyad Mosque (1415–1421 CE), both located in Cairo. The external decoration of the Sultan Qaybtay Mosques (1472–1475 CE) dome is a carved geometrical pattern, one of the earliest examples of its type in Cairo (Yeomans, 2006 ). Combined and complex geometrical patterns are also found in this building, and combinations of 10-, 9-, and 16-point (over the apex) patterns embellish the carved patterns of the dome. Another design element is the combination of 10- and 16-point patterns over the carved vertical panels of the mosques wooden Minbar (Fig. 7 ).

The same styles were repeated in the buildings constructed during the next decades. These buildings include the Amir Qijmas Al-Ishaqi Mosque (1480–1481 CE), Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri Complex, and Wikala of al-Ghori (1505–1515 CE). All three are demonstrations that during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, 16-point and combined geometrical patterns were highly popular among Mamluk architects and artisans. A few examples of 10-point patterns are also evident in the Amir Qijmas Al-Ishaqi Mosque and the Wikala of al-Ghori.

4.6. Ottoman architecture (1290–1923 CE)

A survey of early Ottoman buildings, such as the Yesil Mosque of Iznik (1378–1392 CE) and Ulu-Cami or the Great Mosque of Bursa (1396–1400 CE), shows that early Ottoman buildings are characterized by moderately decorative patterns and that by the end of the 14th century, geometrical patterns were not popular among Ottoman architects and artisans. Except for the extensive 6-, 8-, and 10-point patterns on the walls, ceilings, and doors (Fig. 8 ) of the Yesil Mosque of Bursa (1421 CE), geometrical ornaments are generally only secondary decorative elements in Ottoman buildings. For instance, only a few attractive 6- and 10-point patterns can be found over the main entrance doors, portal, and Minbar of the Bayezid II Complex (1501–1508 CE; Fig. 8 ). The same approach was applied to the Shezade Complex (1544–1548 CE), designed by Ottoman master architect Sinan. Although this mosque is one of the most ambitious architectural masterpieces of the Ottoman Empire (Blair and Bloom, 1995 ), the application of geometrical patterns was limited to only a few 10-point patterns over the mosques Minbar and wooden doors (Fig. 8 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 8. From left: Yesil Mosque in Bursa (first two images); Minbar of Bayezid Complex; wooden doors of Shezade Complex; window crown of Selimiye Complex. |

Some other striking buildings, such as the Suleymaniye Complex (1551–1558 CE), Sokollu-Mehmet-Pasha in Luleburgaz (1560–1565 CE), Haseki-Hurrem Baths (1556 CE), and Sokollu-Mehmet-Pasha in Istanbul (1571–1574 CE), were constructed by Ottomans during the mid-16th century onward. In these structures, geometrical patterns are only secondary decorative features; instead, Iznik tiles with floral motifs form the essential decorative element of these buildings. Among them, the Rustam Pasha Mosque (1560–1563 CE) in Istanbul is the most famous for its exquisite Iznik tile works with floral patterns that cover most of the finishing surfaces. A few 10- and 12-point patterns characterize the design of the wooden doors, Minbar, and wooden ceiling of the right gallery of the main praying hall. These patterns are replicas of the styles that were used in earlier buildings. The Selimiye Complex (1568–1575 CE) in Edirne is the most celebrated and most exquisite building designed by the great architect Sinan (Freely, 2011 ). Similar to most Ottoman buildings, however, the complex features only a few geometrical patterns on its carved marble Minbar and window crowns (Fig. 8 ).

In general, Ottoman architects favored floral and vegetal patterns over geometrical decorations, whose use was limited to door and Minbar panels. Ottoman architects and artisans preferred 6-, 5-, and eventually 10- and 12-point patterns over the 8- and 16-point geometrical patterns that were very popular among Mamluk artisans.

4.7. Safavid architecture (1501–1736 CE)

Safavid architects used geometrical ornaments in both religious and secular buildings. An example of a nonreligious building with geometrical patterns is the Ali-Qapu Palace in Isfahan (1598 CE), having 8- and 10-point patterns on its high columned balcony (Fig. 9 ). Another secular building characterized by an extensive use of geometrical patterns is the Chehel Sutun Palace (1645–1647 CE), also located in Isfahan. The wooden ceiling at its entrance is designed with a variety of geometrical patterns that consist of different 8- and 10-point patterns. Usually in secular buildings, inside elements of geometrical patterns are filled with vegetal motifs, while in many survived religious buildings of this period, geometric ornaments and calligraphic inscriptions are mixed. A remarkable example of this style is the Hakim Mosque of Isfahan (1656–1662 CE). Its facades are highly decorated with tiles and brickwork of geometrical motifs, as well as inscriptions of Nastaliq calligraphy. Similar to the other buildings from this period, the mosque is dominantly embellished with 8- and 10-point patterns; other types of patterns are limited to either grilles or furniture (Fig. 9 ).

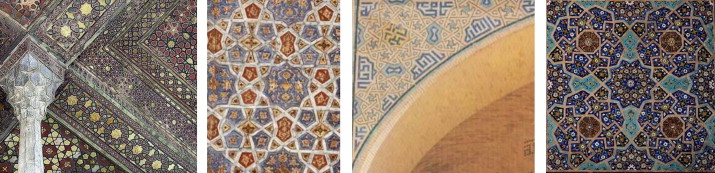

|

|

|

Fig. 9. From left: Ali-Qapu Palace; Chehel-Sutun Palace; Hakim Mosque of Isfahan; Friday Mosque of Isfahan. |

Decorative patterns with geometrical and floral motifs were commonly used in both secular and religious Safavid buildings. These patterns were applied all over internal and external surfaces using carved stucco, wood, colored glasses, polychromatic tiles, lattice, and stone. The processing detail of surviving Safavid decorative patterns shows that these artisans preferred 8- and 10-point geometrical patterns. In contrast to Mamluk architecture, Safavid architecture features fewer combined patterns, but these complex patterns were still common throughout the 16th and 17th centuries in Iran and central Asia.

4.8. Mughal architecture (1526–1737 CE)

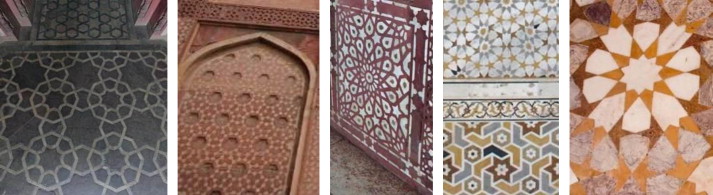

Early surviving Mughal buildings, including the Sher-Shah Mausoleum (1545 CE), are decorated with paintings and tiles of floral motifs. Some highly attractive examples of 6- and 8-point patterns are found on the marble flooring, window grilles, and balcony railings of the Mausoleum of Humayun in Delhi (1566 CE). Dominant 6- and 8-point patterns are also repeated in the Red Fort of Agra (1580 CE). Additionally, some examples of 12-point and very few simple 10-point patterns can be found in this complex (Fig. 10 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 10. From left: Humayun Tomb in Delhi; Red Fort in Agra; Friday Mosque of Fatehpur-Sikri; Etimad-ud-Daulah tomb; Lahore Fort in Pakistan. |

By the end of the 16th century, Mughal architects began to more frequently use 10-point geometrical patterns. The Friday Mosque of Fatehpur-Sikri (1596 CE) is a representative structure of this era. Aside from the various elegant types of 6-, 8-, and 10-point patterns, 14-point geometrical patterns adorn the piers of its main dome (Fig. 10 ); such patterns are the rarest of their kind. Throughout the next decades, geometrical ornaments became an essential decorative element in Mughal architecture, in which vegetal motifs were used as subsidiary and filler decoratives in some cases. The Tomb of Akbar the Great (1612 CE) and the Etimad-ud-Daulah Tomb (1628 in Agra) are representative structures of this period. Both structures are completely covered with inlaid marble and sandstone with 6-,8-, 10-, and 12-point patterns. In terms of geometrical ornaments, another remarkable Mughal building is the Lahore Fort Complex , built during the 16th and 17th centuries. Appealing geometrical patterns embellish the stone floor finishing of the Sheesh-Mahal, the fountain courtyard, and the mosaics of the surrounding wall (Fig. 10 ).

In Mughal architecture, red sandstone, white marble, and polychromatic tiles are the main cladding and decorative materials (Asher, 1992 ). IGPs are one of the key decorative elements of both secular and religious buildings. Unlike their predecessors, particularly the Mamluks, Mughal architects avoided highly detailed geometrical arrangements, such as 12- and 16-point patterns. Instead, they exerted great effort to create accurate and perfect proportions of pattern shapes and angles. Nonetheless, the rarest 14-point geometrical patterns can be found in some Mughal buildings. Another distinguishable feature is that Mughal architects used geometrical patterns in floor finishing designs and carved window railings more than any other Islamic architectural styles.

4.9. Muslims of Spain

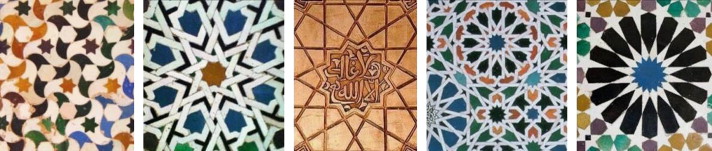

The important surviving buildings of Spains Muslims are the Great Mosque of Cordoba (785–987 CE), Aljaferia Palace in Zaragoza (mid-11th century), and Great Mosque of Seville (1182 CE) (Goodwin, 1991 ). The Alhambra Palace (1338–1390 CE) in Granada is considered one of the most splendid palaces made by Muslims (Clévenot and Degeorge, 2000 ). Almost all the surfaces are richly decorated with the finest floral and geometrical motifs. Although geometrical ornaments were extensively used with profusely colored and intricate renders, highly complex patterns, such as 7-, 9-, and 14-point patterns, are missing. Even a 10-point pattern cannot be found and only the simplest 16-point pattern was applied (Fig. 11 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 11. Alhambra Palace in Spain, showing details of 6-, 8-, 12-, and 16-point geometrical patterns. |

5. Conclusion

This research chronologically and regionally traced the evolution of Islamic geometrical patterns. The results show how regional influence and the prevailing lifestyles during ruling dynasties determined the diversity of Islamic ornaments and geometrical patterns. For example, basic 6- and 8-point geometrical patterns, introduced during the late 9th century, are the most pervasive Islamic ornaments. Aside from their originality, the simplicity in construction of these patterns drove architects to use such ornaments in almost all building elements, from floor finishes to minaret surfaces. Whilst the difficulty of the abstract and the complexity of nonconstructible geometrical patterns limited their application to accessible elements (Qibla walls, window screens), particularly in Iran and central Asia. Another interesting result is that in contrast to the architects and artisans from other Islamic states, those from Anatolia paid less attention to ornaments and geometrical patterns; they focused more extensively on other aspects of architecture, such as form and master planning. For this reason, only a few examples of complex and sophisticated patterns (aside from the simplest ones) can be found in Anatolia.

The relatively stable government and economy during the Mamluk period encouraged architects to design very fine and detailed ornaments that are unique in terms of complexity. The intricate 16-point patterns remained popular in North Africa and Islamic Spain, but only minimally influenced eastern regions, such as Persia, Anatolia, and the Mughal region.

Simpler patterns were popular in the Indian subcontinent, which may be attributed to the passion of Indian artisans for symmetrical designs and their insistence on covering all exterior surfaces with ornaments. Such coverage would be difficult to achieve when complex patterns are used.

5.1. Scientific progress

This research also illustrated scientific progress and knowledge expansion in the history of Islamic architecture. These developments began with simple geometrical shapes constructed from a circle and a set of tangential circles with the same radius (Critchlow, 1976 ), as seen in the Great Mosque of Kairouan during the early 9th century. By the late 9th century, grids of circles were introduced in the Ibn-Tulun Mosque. The grids were used as constructive bases for the simplest regular and semi-regular tiling with equilateral triangles, squares, hexagons, and octagons.

Then, contemporary to rise of Persian philosophers and cosmologists from Abu Sahl Al-Tustari to Sohravadi who had debates and important contribution to nature of numbers and their relation with that of nature (Critchlow, 1989 ), mystical Tetractys motifs and symbol merged to traditional geometric patterns. The result was the invention of abstract 6-point geometrical patterns based on the Tetractys symbol and 12-point star patterns that are associated with 12 zodiacal sectors. These decorative elements adorn the facades of the Tomb of Kharaqan (1067) in Iran. Another number associated with mysticism and cosmology was seven, which represents the seventh heaven in the Islamic perspective. In construction, this number is used to generate a 14-point star, which is a symbol of the Fourteen Infallibles, particularly for Shiite Muslims. Thus, despite the difficulties of building a heptagon, for which no definite method had been established (nonconstructible polygon), Muslim architects built decent approximation methods for drawing heptagons, 7-point stars, and geometrical patterns. This achievement came in concurrence with the rise of the Shiite dynasties in the central provinces of Iran. The earliest examples can be found in the Friday Mosque of Isfahan (1086 CE).

The earliest 10-point geometrical pattern also dates back to the 11th century. The number 10 is not only linked to the Tetractys symbol, but is also a double of a pentagon; an entire book can be written on the golden proportions and sacred properties of the pentagon.

A 9-point geometrical pattern is another example of the influence of cosmological ideas on Islamic geometrical ornaments, particularly during the 11th century. The Enneagram is associated with the Great Conjunction (Jupiter and Saturn conjunction cycle). Enneagon is also a nonconstructible polygon, but Muslim architects discovered its method of approximation in the late 11th century. The introduction of the approximation methods for 7- and 9-sided polygons and stars helped Muslim architects and artisans invent practical approaches to illustrating other nonconstructible polygons and producing relatively accurate 11- and 13-sided polygons and their stars. Some of the earliest examples of these ornaments can be seen in the Barsian Friday Mosque (1098 CE) in Iran.

By the late 12th century, methods of constructing polygons, stars, and patterns on the basis of simple or single-layer circle grids were known throughout the Muslim architectural realm. This development was followed by the introduction of more sophisticated and dynamic patterns based on multi-circle grids. Simpler types were developed by a subgrid associated with an original grid and central points, but under a different scale. This development further popularized the use of more detailed patterns in the early 13th century.

By the early 14th century, along with the advent of the wealthy Mamluk dynasty, more detailed patterns (e.g., 16- and 18-point geometrical patterns) were developed through multiples of primary 8- and 9-point patterns. Finally, highly complex patterns developing from multi-girds of different geometries were discovered. An exquisite example is the door panels in the Sultan Hassan Mosque (1363 CE), which shows a combination of an underlying grid for 16-point geometry and a sub-grid of a 12-point geometrical pattern.

The time chart in Table 1 depicts the evolution of IGPs from their early stages to the late 18th century. In this context, this study demonstrates the suitability of patterns for the buildings inspired by a particular era in terms of relevant time scale accuracy and architectural style matching.

References

- Akkach, 2005 S. Akkach; Cosmology and Architecture in Premodern Islam: An Architectural Reading of Mystical Ideas; State University of New York Press (2005)

- Asher, 1992 C.E.B. Asher; Architecture of Mughal India; Cambridge University Press (1992)

- Behrens-Abouseif, 1992 D. Behrens-Abouseif; Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction; Brill (1992)

- Blair and Bloom, 1995 S. Blair, J.M. Bloom; The Art and Architecture of Islam; Yale University Press (1995)

- Broug, 2008 E. Broug; Islamic Geometric Patterns; Thames & Hudson (2008)

- Clévenot and Degeorge, 2000 D. Clévenot, G. Degeorge; Ornament and Decoration in Islamic Architecture; Thames & Hudson (2000)

- Critchlow, 1976 K. Critchlow; Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach; Schocken Books (1976)

- El-Said et al., 1993 I. El-Said, et al.; Islamic Art and Architecture: The System of Geometric Design; Garnet Pub (1993)

- Fletcher and Cruickshank, 1996 B. Fletcher, D. Cruickshank; History of Architecture; (20th ed.)Architectural Press (1996)

- Flood, 2001 F.B. Flood; The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture; Brill (2001)

- Freely, 2011 J. Freely; History of Ottoman Architecture; WIT Press (2011)

- Goodwin, 1991 G. Goodwin; Islamic Spain; Penguin (1991)

- Grube and Michell, 1995 E.J. Grube, G. Michell; Architecture of the Islamic World: Its History and Social Meaning with a Complete Survey of Key Monuments and 758 Illustrations, 112 in Colour; Thames & Hudson (1995)

- Mohamed, 2000 M. Mohamed; Great Muslim Mathematicians; Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (2000)

- Turner, 1997 H.R. Turner; Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction; University of Texas (1997)

- Yeomans, 2006 R. Yeomans; The Art and Architecture of Islamic Cairo; Garnet Pub. Ltd (2006)

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?