Summary

Background

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an emerging technique for treating superficial neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract. Clinical experience of ESD for superficial colorectal neoplasms remains limited in Taiwan. The aim of this study was to assess ESD performed in a series of patients at our hospital and report the results.

Materials and methods

Thirty-three patients who underwent ESD were retrospectively analyzed for tumor size, rate of en bloc resection, complete resection, curative resection, technical results, and complications.

Results

The tumors treated using ESD were situated in the cecum (n = 6), ascending colon (n = 2), transverse colon (n = 2), descending colon (n = 4), sigmoid colon (n = 9), and rectum (n = 10). The median size of the tumors was 30 mm (range, 10–55 mm). The en bloc resection rate was 72.7%, and the complete resection rate was 66.7%. In patients with en bloc resection, the curative resection rate was 87.5%. Histopathological analysis revealed adenoma with low-grade dysplasia (n = 18), adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (n = 7), and adenocarcinoma (n = 8). Five patients experienced perforation, and the overall complication rate was 15.2%. None of these five patients received surgical treatment.

Conclusion

ESD is a challenging but relatively safe procedure to treat large superficial colorectal neoplasms. However, additional experience is required to achieve higher en bloc resection, complete resection, and curative resection rates.

Keywords

Colon neoplasm ; Endoscopic submucosal dissection ; Rectal neoplasm

Introduction

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) have been used for minimally invasive endoscopic removal of benign or early malignant tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. ESD is a revolutionary procedure enabling en bloc resection of large tumors of the GI tract [1] .

ESD has the advantage over EMR in having higher en bloc resection rate for larger early colorectal tumors [2] . However, ESD to treat colorectal tumors is thought to be particularly dangerous and challenging because the walls of the colon are thinner than those of the stomach, and the leakage of fecal material may lead to serious clinical complications. We therefore evaluated the outcomes of colorectal ESD performed at our hospital.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria for ESD

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of patients with colorectal neoplasms from October 2009 to June 2013 at our institution. Thirty-three patients with colorectal neoplasms who underwent ESD were identified and included in this study. Sixteen patients were asymptomatic and received colonoscopic examinations due to positive fecal occult blood test screening, whereas the other seventeen patients visited our outpatient department due to particular GI symptoms or signs.

The patients who underwent ESD were selected on the basis of the following indications for colorectal ESD proposed by Tanaka et al [3] : (1) large (diameter > 20 mm) tumors for which en bloc resection using snare EMR may be challenging, including nongranular-type laterally spreading tumors, tumors with a type Vi pit pattern, carcinomas with suspected minute submucosal infiltration, and large elevated tumors suspected to be carcinomas; (2) mucosal tumors with fibrosis due to biopsy or mucosal prolapse of the tumor; and (3) local residual tumors after endoscopic resection [3] .

Each lesion was examined preoperatively with narrow-band imaging, chromoendoscopy, and magnifying colonoscopy. To predict the histopathology and depth of tumor invasion, magnifying colonoscopy was used with narrow-band imaging system to identify the pit pattern through its mucosal surface and capillary vessel. Then, 0.4% of indigo carmine dye was sprayed over the lesion to enhance its surface detail to differentiate invasive or noninvasive tumor.

ESD preparation and equipment

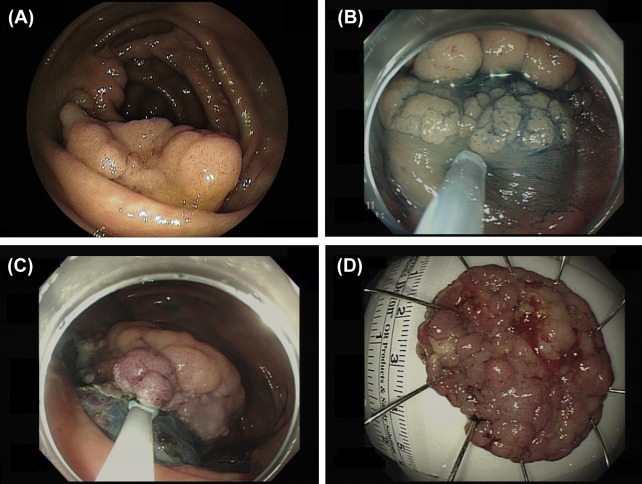

Adequate cleansing of the whole colorectum was conducted before performing endoscopy. We prescribed sodium phosphate solution (Fleet Phosphate-Soda, C.B. Fleet Company, Lynchburg,USA) or polyethylene glycol (Klean-Prep; Helsinn Birex Pharmaceuticals, UK) prior to each procedure to achieve good bowel preparation. The choice of sodium phosphate solution or polyethylene glycol depended on the patient’s age, and renal and hepatic function. For patients receiving examination in the morning, the first bottle/package of sodium phosphate solution (Fleet Phosphate-Soda) or polyethylene glycol (Klean-Prep) is given the night prior to examination at 6 pm , and another bottle/package is given the next morning at 5 am For those receiving examination in the afternoon, the first bottle/package of Fleet Phosphate-Soda or Klean-Prep is given a night prior to examination at 6 pm , and another bottle/package is given the next morning at 9 am Stool color was assessed prior to colonoscopy by a trained nurse and additional bowel preparation was done when necessary. Intravenous midazolam and meperidine were administered to achieve moderate sedation for the procedure. The patients were treated by two endoscopists (H.-H.Y. and C.-W.Y.) in our hospital (Fig. 1 ).

|

|

|

Figure 1. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a colorectal neoplasm. (A) A large laterally spreading granular-type tumor in the cecum. (B) Distal edge of the tumor after submucosal injection of sodium hyaluronate solution. (C) Good visualization of the submucosal tissue during the procedure using the direction of gravity in relation to the location of the tumor. (D) En bloc resection of the entire tumor (42 mm × 31 mm in diameter). A histopathological examination confirmed complete resection (tubulovillous adenoma). |

The equipment used for ESD included Olympus endoscopes (GIF-Q260JI and GIF-H260Z; Olympus) with distal attachment (D-201-12704; Olympus), dual knife (KD-650U; Olympus), IT Knife-2 (KD-611L; Olympus), and an electrosurgical generator (ESG-100; Olympus). The injection solution to lift up the submucosal layer was composed of 10% glycerin, epinephrine (1:100,000), and indigo carmine. We used a CO2 insufflation system (UCR; Olympus) to reduce patient discomfort during the ESD procedure.

ESD procedure and technique

The ESD technique was as follows: The circumference of the lesion was first outlined by marking dots with a dual knife (KD-650U; Olympus) with coagulation current of 40 W (forced coagulation, effect 2) created by the electrosurgical generator (ESG-100). The injection solution was then injected into the submucosal layer around the target lesion to lift the lesion upward, and it was separated from the surrounding normal mucosa by incisions around the lesion using the dual knife (KD-650U) with an electrosurgical current of 50 W (pulse-cut-slow mode). After the circumferential mucosal incisions had been made, the submucosal layer was dissected with the IT Knife-2 or dual knife using an electrosurgical current of 40 W (forced coagulation, effect 2). A distal attachment cap was used to create a better visual field during the mucosal exfoliation procedure. Bleeding control during the procedure was achieved using the IT Knife-2 or dual knife (forced coagulation, effect 2, 40 W), hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper, FD-410LR; Olympus), or hemoclip (HX-610-135; Olympus). The hemostatic forceps were used in the soft coagulation mode (80 W) for vessel hemostasis.

Pathologic assessment

Each resected neoplasm was fixed onto a Styrofoam plate and then placed in a specimen jar, appropriately labeled and reviewed by a pathologist at our hospital. Histological diagnoses were based on the revised Vienna classification of GI epithelial neoplasia.

Definitions of outcomes

En bloc resection was defined as a one-piece resection of an entire tumor observed endoscopically. The residual classification system used to denote completeness of surgical resection was R0, R1, and Rx, where R0 denoted a complete resection with both lateral and basal margins free, R1 denoted incomplete resection at either lateral or basal margins, and Rx denoted margins that were not evaluable due to piecemeal resection or coagulation necrosis. Curative resection was defined as negative resection margins, carcinoma with differentiated histopathology and depth of submucosal invasion < 1000 μm, and no lymphatic or vascular involvement.

Definitions of complications

A complication was defined as either perforation (including immediate perforation or delayed perforation) or postoperative bleeding within 0–14 days after resection. Perforation was defined as a hole recognized during the procedure or free air found in radiography.

Follow-up

We performed follow-up colonoscopies every 6 months during the 1st year after the procedure, and then annually thereafter to assess recurrence. If tumor recurrence was suspected, a biopsy was performed for confirmation.

Results

Thirty-three patients (15 males and 18 females; mean age, 63 years; range, 38–83 years) with colorectal neoplasms underwent ESD at our hospital from October 2009 to June 2013 (Table 1 ). Sixteen of the patients received colonoscopic examinations due to positive fecal occult blood test screening, all of whom were asymptomatic and had no family history of colorectal cancer. Ten patients received colonoscopic examinations due to blood-tinged stools, and another seven received colonoscopic examinations due to abdominal discomfort (tenesmus and abdominal fullness).

| Characteristics of patients and lesions treated using ESD (n = 33) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 15/17 |

| Age, mean (y) | 63 (range, 38–83) |

| Asymptomatic, FOBT positive | 16 (48.5) |

| Symptoms/signs | |

| Blood-tinged stool | 10 (30.3) |

| Abdominal discomfort | 7 (21.2) |

| Smoking | 8 (24.2) |

| Alcohol | 3 (9.0) |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | 3 (9.0) |

| Lesions’ location | |

| Cecum | 6 (18.2) |

| Ascending colon | 2 (6.05) |

| Transverse colon | 2 (6.05) |

| Descending colon | 4 (12.1) |

| Sigmoid colon | 9 (27.3) |

| Rectum | 10 (30.3) |

| Gross finding | |

| LST | 32 (97) |

| Granular type | 25 |

| Nongranular type | 7 |

| Sessile | 1 (3) |

| Pit pattern, Kudo’s classification | |

| IIIs | 8 (20) |

| IIIl | 8 (20) |

| IV | 11 (30) |

| Vi | 5 (20) |

| Vn | 1 (10) |

| Tumor size, mean (mm) | 30 (range 10–55) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

ESD = endoscopic submucosal dissection; FOBT = fecal occult blood test; LST = lateral spreading tumor.

The tumors treated using ESD were located in the cecum (n = 6), ascending colon (n = 2), transverse colon (n = 2), descending colon (n = 4), sigmoid colon (n = 9), and rectum (n = 10). Macroscopically, the appearance of the lesions revealed sessile (n = 1), laterally spreading tumor granular (n = 25), and laterally spreading tumor nongranular (n = 7) types. Using magnifying endoscopy and narrow-band imaging, we identified pit pattern type IIIs (n = 8), IIIl (n = 8), IV (n = 11), Vi (n = 5), and Vn (n = 1). The median size of the tumors was 30 mm (range, 10–55 mm). Two patients with tumors measuring 10 mm and 12 mm (<20 mm), respectively, were included due to incomplete resection of previous EMR with scar tissue, which the pathology showed to be adenoma with low-grade dysplasia. One patient with pit pattern type Vn was included in this study. The tumor was located over the inlet of the rectum, and was 32 mm in size with a nonstructural pit pattern over the center without fold convergence. However, the patient insisted to try ESD resection even though the risks of additional surgery were carefully explained. We then performed endoscopic ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography to evaluate the suitability for ESD. The endoscopic ultrasound showed that the tumor involved mostly the mucosal layer; however, partial submucosal invasion was suspected. Abdominal computed tomography showed no evidence of lymph node metastasis. ESD was therefore performed and achieved en bloc resection and complete resection (R0). The pathology revealed well-to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma without lymphatic or vascular invasion; however, the depth of submucosal invasion was > 1,000 μm. We subsequently referred this patient for surgery due to the risk of lymph node metastasis.

The outcomes of the ESD procedures are presented in Table 2 . En bloc resections were performed successfully in 72.7% of the patients, with a complete resection (R0) rate of 66.7%. None of the patients had lymphatic or vascular invasion microscopically. Of the 24 patients with en bloc resection, two had incomplete resection clear margins and one had adenocarcinoma with submucosal invasion. The curative resection rate was 87.5%.

| Colorectal neoplasms (n = 33) | |

|---|---|

| En bloc resection | 24 (72.7) |

| Completeness of surgical resection | |

| R0 | 22 (66.7) |

| R1 | 9 (27.2) |

| Rx | 2 (6.1) |

| Curative resection | 21 (87.5) |

| Complication | |

| Perforation | 5 (15.2) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 0 (0) |

| Pathology | |

| Adenoma | |

| Low-grade dysplasia | 18 (54.6) |

| High-grade dysplasia | 7 (21.2) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 8 (24.2) |

| Lymphatic invasion | 0 (0) |

| Vascular invasion | 0 (0) |

| Submucosal invasion > 1000 μm | 1 (3) |

| Follow-up time, d a | Range, 92–1125 |

| Recurrence | 0 (0) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

a. One patient was lost to follow-up.

We found it technically difficult to dissect the lesion as a whole piece in nine patients, and they subsequently underwent piecemeal EMR. Among these nine patients without en bloc resection, five were among the first 10 ESD procedures we attempted. This result may therefore be related to our inadequate experience in handling the ESD technique, and the en bloc resection success rate improved as we gained experience. Among the nine unsuccessful en bloc resections, six had no tumor recurrence in follow-up colonoscopy, two were referred for surgery due to incomplete resection, and one patient was lost to follow-up.

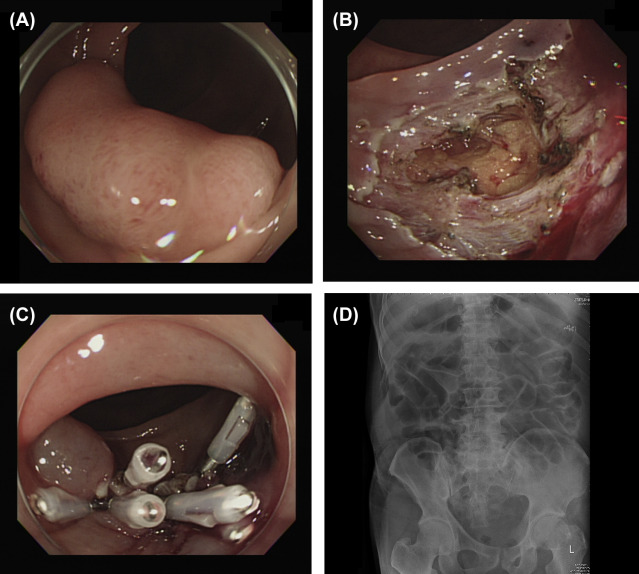

Histopathology revealed adenoma with low-grade dysplasia (n = 18), adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (n = 7), and adenocarcinoma (n = 8). None of these patients had recurrence in follow-up colonoscopy, with the longest follow-up period being 1125 days and the shortest being 92 days. However, two patients, including the one with piecemeal resection, did not receive follow-up colonoscopy at our hospital. Perforations occurred in two patients who underwent ESD, which were successfully closed with endoscopic hemoclips ( Fig. 2 ). These patients were hospitalized without oral feeding for 3 days and 5 days, respectively, and given broad-spectrum antibiotics with close monitoring for possible leakages. Another three patients were found to have pneumoperitoneum after the procedure but without any peritoneal signs, and they were observed for a few days in our hospital. All five patients were discharged smoothly without other complications.

|

|

|

Figure 2. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) perforation. (A) A laterally spreading tumor about 3.0 cm in size in the transverse colon. (B) Perforation of about 2 cm with the omentum underneath identified after ESD. (C) Hole sealed with endoscopic hemoclips. (D) No free air was found on radiography after ESD. |

Discussion

Endoscopic resection of superficial GI tumors has advanced with the development of new endoscopic tools and techniques. Advancements in device-dependent techniques including high-magnification endoscopy, image-enhanced endoscopy, and endoscopic ultrasound have enabled instant and precise diagnoses prior to surgery.

ESD using an insulation-tipped diathermic knife (IT knife) was first reported in the literature by Hosokawa and Yoshida [4] in 1998. Gotoda et al [5] reported the first use of rectal ESD in 1999. Both EMR and ESD have been recommended for their minimally invasive and organ-sparing tumor removal. However, ESD has several benefits compared with EMR. First, it enables en bloc resection of large tumors (usually > 2 cm) in the GI tract [1] , whereas piecemeal resection usually requires EMR. Second, it is more reliable for en bloc resection of a targeted mucosal area, providing a higher complete resection rate with a lower recurrence rate compared with piecemeal EMR [2] . Since the first reports on the use of ESD, it has been employed in the gastric area, esophagus, colon, and rectum [6] . However, performing colorectal ESD is still considered dangerous and challenging, particularly because of the thin colorectal walls with higher perforation risk and serious clinical complications, such as peritonitis, resulting from fecal material leakage.

Currently, ESD for GI tract tumors is performed in only a limited number of hospitals in Taiwan [7] ; [8] ; [9] ; [10] ; [11] ; [12] ; [13] ; [14] ; [15] ; [16] . Our initial experience with colorectal ESD in 33 patients demonstrated an en bloc resection rate of 72.7%, complete resection rate of 66.7%, and curative resection rate of 87.5%. We encountered difficulties with en bloc resection in nine patients, in whom two tumors were located in the cecum, two in the sigmoid colon, one in the ascending colon, one in the descending colon, and three in the rectum. Despite careful dissection and a long procedure time, we accidentally made deep submucosal dissections and had problems dissecting the tumors behind the fold during the procedure. We subsequently discontinued en bloc resection and performed piecemeal EMR due to the concerns of perforation. These unsuccessful en bloc resections were mainly due to our inadequate experience in handling the colorectal ESD technique. This highlights the importance of having experienced ESD colonoscopists conduct and supervise colorectal ESD procedures, and this may also be one of the limitations encountered by a gastroenterologist department hoping to use this procedure.

One case with a relatively controversial indication for colorectal ESD had a nonstructural pit pattern over the center of the 30-mm laterally spreading granular-type tumor. This suggested submucosal invasion and surgery should have been the treatment option; however, although we explained the risks of additional surgery after ESD, the patient still wanted to undergo ESD. The pathology study later showed adenocarcinoma with submucosal invasion (> 1000 μm below the muscularis mucosae), and the patient received additional surgery. Some long-term outcome studies for endoscopic resection of submucosal invasive colorectal tumor, either with EMR or ESD, have shown that endoscopic resection alone for a tumor with high-risk features has higher recurrence rate than surgery, with reported recurrence rates of 6.6–16.2% [17] ; [18] . The high-risk features are lesions not fulfilled with (1) complete resection, (2) well-differentiated or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, (3) absence of vascular invasion, and (4) depth of submucosal invasion < 1000 μm. Additional surgery is recommended for tumors with high-risk features [17] ; [18] Colonoscopists should be familiar with narrow-band imaging, chromoendoscopy, and magnifying endoscopy to predict the histopathology of the neoplasms and judge the depth of the tumor preoperatively, and then decide the most suitable treatment option for the patient.

Bleeding was controlled intraoperatively in all patients by thermal coagulation, hemostatic forceps, or mechanical clipping. We recognized holes in two of the patients during the resection. These holes were identified immediately, and endoscopic rescue procedures were carried out using hemoclips to seal the holes. Neither patient received further surgical treatment, and both were discharged after conservative treatment. Another three patients were found to have intra-abdominal free air by KUB after ESD; however, none of them had abdominal pain or fever. Conservative treatment was provided and they all recovered smoothly. No postoperative bleeding occurred in the patients. A summary of previous reports on 2719 patients from 13 single-institution studies demonstrated an en bloc resection rate of 82.8% and a complete resection rate of 75.7%, with perforation and postoperative bleeding rates of 4.7% and 1.5%, respectively [19] . The lower en bloc resection and complete resection rates in our study were most likely related to our limited experience in handling the ESD technique for colorectal neoplasms.

It is essential to plan a suitable strategy to approach the tumors, and this strategy should consider the incision angle and the gravitational effect on the colonic neoplasm. Gravity facilitates better visualization of the submucosal tissue after tumor dissection because blood flows away from instead of pooling at the bleeding point, making hemostasis easier. In addition, some reports have suggested that this position can minimize the possibility of diffuse peritonitis in cases of perforation, because air flows out of the lumen first rather than colonic fecal material [20] . The soft, thin colorectal walls and paradoxical movement of the colon also increases the risk and challenges in manipulation of colorectal ESD. Moreover, despite using a retroflex approach, we found it difficult to dissect tumors that were located over or behind the prominent fold of the colon in some of the initial cases. This problem was later overcome as we performed more colorectal ESD procedures and became more familiar with the use of the distal attachment, which provided a better view of the site and also easier manipulation of the procedure.

At our hospital, the prerequisites for endoscopists to proceed with colorectal ESD include possessing the skills necessary for successful insertion of colonoscopes, performing EMR and piecemeal EMR, and completing a certain number of gastric ESD procedures. Our experience demonstrates that piecemeal EMR may be an option when en bloc ESD is unsuccessful. The tumors in the nine patients, which involved particularly challenging en bloc resections, were subsequently resected using piecemeal EMR without any serious complications. Among these nine unsuccessful en bloc resection lesions, six had no tumor recurrence in follow-up colonoscopy, two were referred for surgery due to incomplete resection, and one patient was lost to follow-up. Large-scale endoscopic resection studies demonstrated that although ESD had a higher en bloc resection rate for larger tumor, EMR or piecemeal EMR had a similar low recurrence rate and could manage most early colonic tumor adequately [21] ; [22] ; [23] .

Besides the long learning curve of colonic ESD, teamwork among endoscopists, nurses, surgeon, and pathologist is essential in colonic ESD. The training of the ESD assistant is another issue that should be overcome while performing some complex technique. Our hospital pathologist has given effort in determining the resected specimen and conferences are held to discuss the pathologic outcome of the specimen. Endoscopic specimen is assessed using a standard 5-mm slice interval. However, specimen with high-risk features will be inspected using 2-mm slice interval. During our initial 10 cases of colonic ESD, we informed our surgeon about the risk of colonic perforation and requested them to standby prior to the resection in case of accidental complication.

ESD training programs using ex vivo pig models in Taiwanese hospitals allow young endoscopists to familiarize with ESD techniques [24] . After an endoscopist is familiar with ESD techniques in animals, including the delineation of adequate safety margins, adequate management of challenging ESD, and endo-knife manipulation, the endoscopist can proceed to human ESD. In the interim, appropriate maneuvers such as EMR, piecemeal EMR, ESD, laparoscopic resection, or laparotomy should be selected depending on the status and characteristics of the tumor, the operator’s technical skill, and the facilities at the hospital.

The limitations of the current study include the results being from only a single hospital and the small number of cases enrolled.

In summary, our experience demonstrated that ESD remains a challenging but relatively safe procedure for treating large superficial colorectal neoplasms. However, additional experience is required to achieve higher en bloc resection, complete resection, and curative resection rates, with lower complication rate.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented at the 2011 Annual Meeting of the Gastroenterological Society of Taiwan and The Digestive Endoscopy Society of Taiwan. The authors thank Professor Kuang-I Fu (Department of Gastroenterology, Juntendo University Nerima Hospital, Tokyo, Japan) for setting up and teaching the essential ESD techniques at Changhua Christian Hospital.

References

- [1] T. Gotoda, H. Kondo, H. Ono, Y. Saito, H. Yamaguchi, D. Saito, et al.; A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases; Gastrointest Endosc, 50 (1999), pp. 560–563

- [2] Y. Saito, M. Fukuzawa, T. Matsuda, S. Fukunaga, T. Sakamoto, T. Uraoka, et al.; Clinical outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal tumors as determined by curative resection; Surg Endosc, 24 (2010), pp. 343–352

- [3] S. Tanaka, S. Oka, K. Chayama; Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: present status and future perspective, including its differentiation from endoscopic mucosal resection; J Gastroenterol, 43 (2008), pp. 641–651

- [4] K. Hosokawa, S. Yoshida; Recent advances in endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer; Gan To Kagaku Ryoho, 25 (1998), pp. 476–483

- [5] T. Gotoda, H. Kondo, H. Ono, Y. Saito, H. Yamaguchi, D. Saito, et al.; A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases; Gastrointest Endosc, 50 (1999), pp. 560–563

- [6] T. Oyama, A. Tomori, K. Hotta, S. Morita, K. Kominato, M. Tanaka, et al.; Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 3 (2005), pp. S67–S70

- [7] N. Uedo, H.Y. Jung, M. Fujishiro, I.L. Lee, P.H. Zhou, P.W. Chiu, et al.; Current situation of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial neoplasms in the upper digestive tract in East Asian countries: a questionnaire survey; Dig Endosc, 24 (2012), pp. 124–128

- [8] C.T. Lee, C.Y. Chang, C.M. Tai, W.L. Wang, C.H. Tseng, J.C. Hwang, et al.; Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal neoplasia: a single center experience in South Taiwan; J Formos Med Assoc, 111 (2012), pp. 132–139

- [9] C.H. Li, P.J. Chen, H.C. Chu, T.Y. Huang, Y.L. Shih, W.K. Chang, et al.; Endoscopic submucosal dissection with the pulley method for early-stage gastric cancer (with video); Gastrointest Endosc, 73 (2011), pp. 163–167

- [10] H.H. Yen, C.J. Chen; Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp; J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 25 (2010), p. 1465

- [11] C.W. Yang, H.H. Yen, Y.Y. Chen, M.S. Soon, C.J. Chen; Novel use of the tip of a standard diathermic snare for endoscopic submucosal dissection of a large gastric adenomatous polyp; J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, 22 (2012), pp. 910–912

- [12] H.M. Chiu, J.T. Lin, M.S. Wu, H.P. Wang; Current status and future perspective of endoscopic diagnosis and treatment for colorectal neoplasia—situation in Taiwan; Dig Endosc, 21 (2009), pp. S17–S21

- [13] C.C. Chang, I.L. Lee, P.J. Chen, H.P. Wang, M.C. Hou, C.T. Lee, et al.; Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial tumors: a multicenter study in Taiwan; J Formos Med Assoc, 108 (2009), pp. 38–44

- [14] I.L. Lee, C.S. Wu, S.Y. Tung, P.Y. Lin, C.H. Shen, K.L. Wei, et al.; Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers: experience from a new endoscopic center in Taiwan; J Clin Gastroenterol, 42 (2008), pp. 42–47

- [15] C.C. Chang, C. Tiong, C.L. Fang, S. Pan, J.D. Liu, H.Y. Lou, et al.; Large early gastric cancers treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection with an insulation-tipped diathermic knife; J Formos Med Assoc, 106 (2007), pp. 260–264

- [16] I.L. Lee, P.Y. Lin, S.Y. Tung, C.H. Shen, K.L. Wei, C.S. Wu; Endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of intraluminal gastric subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer; Endoscopy, 38 (2006), pp. 1024–1028

- [17] Y. Yoda, H. Ikematsu, T. Matsuda, Y. Yamaguchi, K. Hotta, N. Kobayashi, et al.; A large-scale multicenter study of long-term outcomes after endoscopic resection for submucosal invasive colorectal cancer; Endoscopy, 45 (2013), pp. 718–724

- [18] H. Ikematsu, Y. Yoda, T. Matsuda, Y. Yamaguchi, K. Hotta, N. Kobayashi, et al.; Long-term outcomes after resection for submucosal invasive colorectal cancers; Gastroenterology, 144 (2013), pp. 551–559

- [19] S. Tanaka, M. Terasaki, H. Kanao, S. Oka, K. Chayama; Current status and future perspectives of endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors; Dig Endosc, 24 (2012), pp. 73–79

- [20] H. Yamamoto; Endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors; Front Gastrointest Res, 27 (2010), pp. 287–295

- [21] A. Moss, M.J. Bourke, S.J. Williams, L.F. Hourigan, G. Brown, W. Tam, et al.; Endoscopic mucosal resection outcomes and prediction of submucosal cancer from advanced colonic mucosal neoplasia; Gastroenterology, 140 (2011), pp. 1909–1918

- [22] T. Nakajima, Y. Saito, S. Tanaka, H. Iishi, S.E. Kudo, H. Ikematsu, et al.; Current status of endoscopic resection strategy for large, early colorectal neoplasia in Japan; Surg Endosc, 27 (2013), pp. 3262–3270

- [23] H.M. Chiu, J.T. Lin; Clinical application and standardization of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: is it a viable approach?; J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 28 (2013), pp. 391–393

- [24] T.E. Wang, H.Y. Wang, C.C. Lin, T.Y. Chen, C.W. Chang, C.J. Chen, et al.; Simulating a target lesion for endoscopic submucosal dissection training in an ex vivo pig model ; Gastrointest Endosc, 74 (2011), pp. 398–402

Document information

Published on 15/05/17

Submitted on 15/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?