Abstract

This study focused on the structure and the platform of the road space of historic districts. We analyzed the road networks of 16 historic districts in Japan from the perspectives of circularity, accessibility and indirection based on graph theory. By calculating and comparing the indexes of each road network (NW1 and NW2) forms, we quantitatively describe the effects of the main prefectural roads (more than 4 m in width) and narrow streets (less than 4 m in width) on the spatial characteristics. And it turned out that we could divided the 16 objective historic districts into 4 types. Moreover, we qualitatively studied the characteristics of each type of historic districts based on their development background and the structure of road network.

Keywords

Road network forms ; Historic districts ; Graph theory ; Circularity ; Accessibility

1. Introduction

Many cities and villages in Japan have a long history. The spatial form of these historic districts has changed with the progression of urbanization, but many such districts and villages still apply old road networks as spatial frameworks. These frameworks contain not only old streets that serve as the main prefectural roads but also winding narrow alleys that are less than 4 m wide. Although traffic capacities vary, these streets complement one another and jointly constitute the road network form that fits the local lifestyle while maintaining the uniqueness of the area. People wandering in these historic districts are often fascinated by the sequence landscape along the road and the rich variations in the road itself. Thus, these historic streets must be preserved in merging modern urban design with the characteristics of the local area.

Since Japan established the Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings in 1975, an active movement has been initiated to protect and re-develop historic districts throughout the country. Given the sub-optimal awareness regarding the spatial structure of historic districts in preparing local development plans, many old streets were modified after being regarded as unfavorable factors that impede traffic. As a result, the road network in some originally unique historic districts changed and a few historical surroundings were demolished. Apart from recognizing the importance of historic streets from the perspectives of landscape and culture, the features of spatial structures must be interpreted objectively to avoid conflicts between the re-development of historic districts and the preservation of the historic environment.

On the basis of the afore mentioned viewpoints, 16 historic districts of various formation backgrounds in Japan were taken as examples in this study to analyze the circularity, accessibility, and indirection of the road network individually. This procedure can help quantitatively clarify the features of the road network form in these districts and explore the relationship between road formation and spatial characteristics further.

2. Previous studies

To date, researchers in many disciplines have studied the spatial features of historic roads in Japan. In geographic research, for example, historic streets in Japan were classified according to natural and artificial road formation conditions, and the relationship between the characteristics of road sections and the use of land along the road was identified (Rin et al., 1995 ; Kamae et al., 1995 ). In landscape-related studies, the roles of the historic roads in the area within the sequence landscape were explored by analyzing the shapes and angles of the roads and of the surrounding physical environment (Iwakuma, 1997 ; Miyawaki, 2012 ; Kawakami et al., 2012 ). In papers discussing local communities, the influence of road spatial features in various scales on the communication behavior within the neighborhood inside blocks was determined through field investigations into the environment of historic roads in Kyoto and the functions of the buildings along the roads (Okada and Miyazaki, 2012 ).

The results from the afore mentioned studies indicate that historic road space plays an important role in the formation of local communities and in the continued implementation of urban characteristics in Japan. However, most previous works described the physical characteristics of road spaces from their respective viewpoints. Moreover, research on the overall composition and potential non-visual characteristics of historic road networks in Japan remains scarce.

In studies that examine the re-development of historic regions, many historic districts may emphasize accessibility and circularity; researchers argue that some old streets are highly circuitous and thus contribute little to traffic (Kozuka et al ., 2005 ; Shimizu and Ono, 2006 ; Aoki et al ., 2010 ). Hence, proposals to demolish and change original road network structures have been presented. However, problems regarding the exact situation of the original road network and the extent to which certain roads affect the overall characteristics of the area are rarely addressed objectively (Tanaka and Akasaki, 2000 ; Nishiguchi, 2004 ).

In the current study, we focus on the structure and the platform of the road space. Furthermore, we analyze the spatial characteristics of the road networks in historic districts with different formation backgrounds in terms of three aspects that have attracted much attention in regional development, namely, circularity, accessibility, and indirection (Punnoi et al ., 2010 ; Miyashita et al ., 2013 ). This analysis can help quantitatively illustrate the spatial characteristics and the status quo of the historic roads. This study also presents methods and basic data to effectively recognize road space for coordinating future development plans related to historic regions (Fig. 1 ).

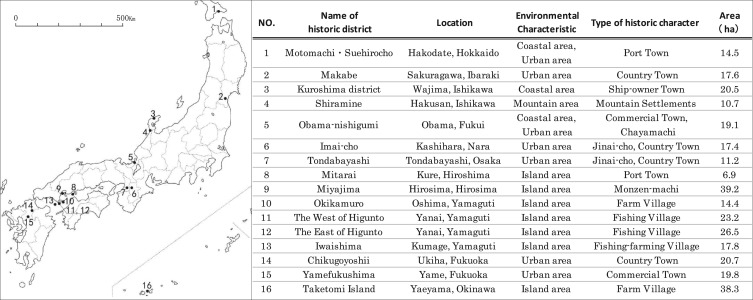

|

|

|

Fig. 1. The basic information of the research areas. |

3. Research method

3.1. Indicators

In this study, the circularity, accessibility, and indirection of road networks are defined based on graph theory (Watanabe et al., 1983 ). The selected indicators that can be used to quantitatively describe the geometric features of these aspects are listed in Table 1 .

| Categories | Indices | Formula | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circularity | Cyclomatic number: µ | µ =e −ν +p | e : Number of links ν : Number of nodes P : Number of component |

| Average Cyclomatic number: µa (n/ha) | µa =µ /S | S : Area | |

| α -index (%) | α=µ /(2ν −5) | In copmplete connected network, µc =2ν −5 Ratio of µ /µc | |

| β -index | β =e /ν | Average number of pass per node | |

| γ -index (%) | γ =e /3(ν −2) | In copmplete connected network, ec =3(ν −2) Ratio of e /ec | |

| Accessibility | Average accessibility: Ai | Average minimum distance from all nodes to node i , d (i ,j ): minimum distance of inter nodes | |

| Average dispersion: Di | Excepted effect of number of nodes from sum of Ai | ||

| Road density: Dl (m/ha) | Dl =L /S | L : Total length S : Area | |

| Node density: Dc (n/ha) | Dc =νc /S | νc : Number of intersection S : Area | |

| Indirection | Detour ratio A ′ | Average ratio of minimum distance to straight-line distance from all nodes to node i , d (i ,j ) | |

| Average detour ratio A | Average ratio of minimum distance to straight-line distance of inter network |

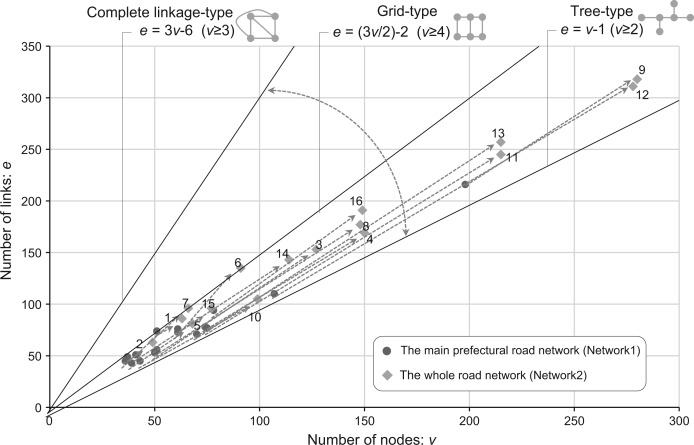

First, the circularity of the road network refers to the extent of repetition by people wandering around the road network purposelessly (Takagi et al., 1991 ). From a geometrical point of view, this metric depends on the number of circular roads in the network and the number of nodes and links that constitute the circular road (Beineke and Wilson, 1978 ; Ando et al., 2001 ). Therefore, circularity can be evaluated through three indicators α , β , and γ ( Sakai and Naya, 1992 ; Saito, 2002,2011 ). If any given link in a network is removed, thereby preventing the formation of a complete graph, then the graph is considered a “tree-type” graph. If every node in the graph can be connected directly, then the graph is regarded as a “complete link age-type” graph. As shown in Fig. 2 , plane network graphs are generally either “tree-type” or “complete link age-type” graph. The form type of the graph can be determined based on the mathematical relationship between the links and the nodes. In this study, the number of circular roads in the network is represented by μ . The α indicator refers to the ratio of the number of circular roads when the nodes in the graph are completely linked to one another to the actual number of the circular roads. The β indicator denotes the ratio of the number of nodes to the number of links in the graph. This ratio represents the average number of corresponding links to each of the nodes. The γ indicator refers to the ratio of the number of the links required to completely link all the nodes in the graph to the actual number of roads. These indicators complement one another and jointly depict the extent of road network circularity. The higher the value is, the better the relative road network circularity is.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. Road network form of research area (Relationship between numbers of links and nodes). |

Second, Ai , which is the average of the minimum distances between any given nodes to any other nodes in the graph, is used to assess the accessibility of a given no debased on the concept of distance (Graham et al., 1977 ). In addition, Di , which is the average of the Ai values of all the nodes, is applied to assess the accessibility of the overall road network. Therefore, the smaller the value of Di is, the shorter the relative distance required for the wanderers in the road network to reach each of the nodes and the better the accessibility of the overall road network. A few studies have indicated that the extent and densities of the nodes and links in the network graphs are directly related to the Di indicator ( Koshizuka, 1978 ; Takagi et al ., 1991 ). In the present study, road network density (Dl ) and node density (Dc ) are utilized to jointly evaluate road network accessibility.

Finally, indirection is defined as the ratio of the actual distance from a certain node to any of the other nodes to the linear distance between the two nodes in the graph. Detour rate (A ) is applied to represent the extent of overall road network indirection ( Tamura et al., 2001 ). The higher the detour rate is, the stronger the indirection of the road network is, i.e., the more circuitous a path a person must take to reach a given node.

3.2. Research area

Sixteen villages and city blocks whose historic roads have been well preserved were selected as the objects of analysis based on the following three criteria. The location and features of each district are shown in Fig. 1 .

- Taking into account the effect of the formation background of the historic district on the form of its road network, representative districts were selected. These districts range from traditional villages that rely on agriculture, forestry, and fishery to historic city blocks that depend on industrial or religious facilities.

- In consideration of the effects of geographical conditions, the subjects included relatively independent areas located in between the island and mountain and areas situated in or are close to cities.

- To minimize the influence of modern roads on the form of the historic road network as much as possible, the appropriate subjects were selected as follows: (1) villages with well-preserved original road networks that remain in use based on historical records and local archives; (2) areas that are close to cities but are only slightly affected by urbanization, with most of the road network remaining unchanged; and (3) areas that belong to the Important Preservation Districts for Groups of Traditional Buildings and the city blocks that maintain their original historic road form.

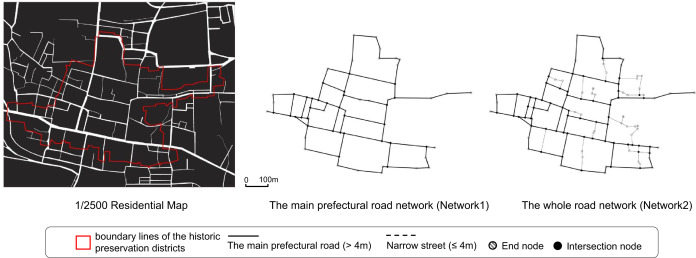

3.3. Road network mapping

According to the general method of graph theory and considering the different actual road formations of each of the subjects, four rules were set to generate a road network for each of the subjects (Fig. 3 b).

- First, the range of graphs for national or local historical preservation districts is based on the boundary lines that are clearly marked on the city plan. Second, the range of the boundary lines in naturally formed traditional villages is wide given the inclusion of mountain areas and farmland. To compare the subjects at a similar scale, the major residence areas of the traditional villages with relatively densely populated roads were selected to represent the graphing range of the road network.

- Considering that the types of roads within the road network differ and thus exert varied influences on the characteristics of the overall form (Yamazaki et al., 2013 ), the road network structure was divided into main prefectural roads (more than 4 m wide) and narrow streets (less than 4 m wide) based on the information reflected in the 1/2500 Residential Map of Japan. Accordingly, the relationship between road formation and each of the spatial characteristics was clarified. The main prefectural road network (NW1) and the narrow streets in the entire road network (NW2) were analyzed individually (Fig. 3 a).

- The plane forms of the road in this study are divided into straight lines, tortuous lines, and curves. A road that has a low extent of tortuousness has a straight line form if the two ends of the road can be linked by one straight line within the width of the road.

- In Fig. 3 , the terminal node (no link at the other end) of each line is represented by

, and the intersection node is represented by •.

|

|

|

Fig. 3. (a) The type of road network (Take 14. Chikugoyoshii for example). (b) Road network in the research areas. |

4. Result and analysis

4.1. Circularity characteristics

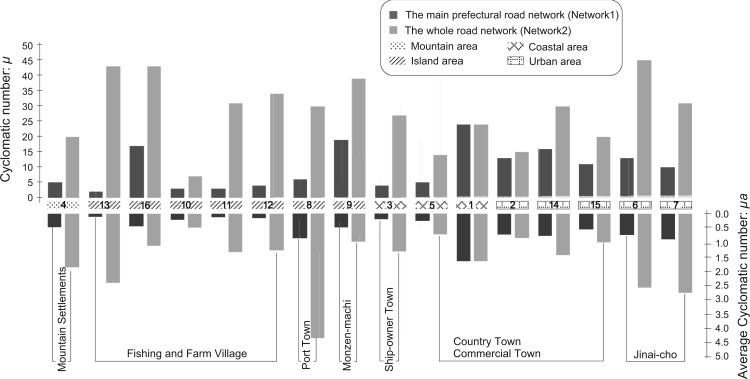

The analysis results of the 16 districts are presented in Table 2 . First, in terms of the number of circular roads (μ ), the value for the historic city blocks of 1.Motomachi·Suehirocho and other cities is over 10 for the main road network (NW1). This value is higher than that of other areas. By contrast, the number of circular roads corresponding to the unit area of 1 ha in Miyajima and Taketomi is low because of the large area of the districts, although the μ values of these regions are high (Fig. 4 ). Therefore, the historic city blocks in cities formed more circular roads than the traditional villages in island and mountain areas did as per a comprehensive examination of the status of the main prefectural road. As a result, road network circularity improves. Upon analyzing the entire road network (NW2) that includes narrow streets less than 4 m wide, the total number of circular roads (μ ) and the average of the unit areas of the traditional villages in 13.Iwaishima and 11.Higunto are significantly higher than the results obtained in the NW1 analysis; in fact, the findings for NW2 are roughly equivalent to the results for the historic city blocks in cities ( Fig. 4 ). This finding suggests that roads less than 4 m wide between two resident houses strongly influence the formation of circular roads in the road network of the traditional villages. This effect strengthens the link among the main prefectural roads and further subdivides the road network.

| Type | NO. | Name of historic district | Road length (m ) | Network1 (The main prefectural road network) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length | Main Road (>4 m) | Narrow Street (<4 m) | e | ν | Number of end point | Number of intersection | µ | µa | α (%) | β | γ (%) | Di (m) | Dl (m/ha) | Dc | A | |||

| Type1 | 4 | Shiramine | 3725 | 2418 | 1307 | 78 | 74 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0.5 | 3 | 1.1 | 36 | 347 | 226 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| 13 | Iwaishima | 6311 | 2599 | 3711 | 71 | 70 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 1.0 | 35 | 515 | 146 | 0.4 | 1.6 | |

| 16 | Taketomi Island | 7914 | 4546 | 3368 | 94 | 78 | 0 | 30 | 17 | 0.4 | 11 | 1.2 | 41 | 474 | 119 | 0.8 | 1.3 | |

| 10 | Okikamuro | 2857 | 1565 | 1293 | 45 | 43 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 0.2 | 4 | 1.0 | 37 | 252 | 109 | 0.6 | 1.2 | |

| 11 | The West of Higunto | 5861 | 2854 | 3007 | 77 | 75 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 0.1 | 2 | 1.0 | 35 | 527 | 123 | 0.5 | 1.3 | |

| 12 | The East of Higunto | 7867 | 3965 | 3902 | 110 | 107 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.0 | 35 | 697 | 150 | 0.5 | 1.7 | |

| Type2 | 3 | Kuroshima district | 3993 | 2144 | 1849 | 53 | 50 | 0 | 9 | 4 | 0.2 | 4 | 1.1 | 37 | 339 | 105 | 0.4 | 1.5 |

| 5 | Obama-nishigumi | 3656 | 2502 | 1154 | 43 | 39 | 1 | 12 | 5 | 0.3 | 7 | 1.1 | 39 | 384 | 131 | 0.6 | 1.3 | |

| 8 | Mitarai | 4124 | 2236 | 1889 | 56 | 51 | 1 | 13 | 6 | 0.9 | 6 | 1.1 | 38 | 306 | 324 | 1.9 | 1.4 | |

| 9 | Miyajima | 9424 | 7181 | 2243 | 216 | 198 | 0 | 36 | 19 | 0.5 | 5 | 1.1 | 37 | 738 | 183 | 0.9 | 1.7 | |

| Type3 | 1 | Motomachi·Suehirocho | 6572 | 6361 | 212 | 74 | 51 | 0 | 37 | 24 | 1.7 | 25 | 1.5 | 50 | 430 | 439 | 2.6 | 1.2 |

| 2 | Makabe | 4608 | 4245 | 363 | 49 | 37 | 0 | 23 | 13 | 0.7 | 19 | 1.3 | 47 | 350 | 241 | 1.3 | 1.2 | |

| 14 | Chikugoyoshii | 6835 | 5207 | 1628 | 76 | 61 | 0 | 30 | 16 | 0.8 | 14 | 1.2 | 43 | 428 | 252 | 1.4 | 1.3 | |

| 15 | Yamefukushima | 5697 | 4428 | 1269 | 51 | 41 | 0 | 20 | 11 | 0.6 | 14 | 1.2 | 44 | 474 | 224 | 1.0 | 1.3 | |

| Type4 | 6 | Imai-cho | 6820 | 4929 | 1891 | 73 | 61 | 0 | 27 | 13 | 0.7 | 11 | 1.2 | 41 | 400 | 283 | 1.6 | 2.3 |

| 7 | Tondabayashi | 4036 | 2757 | 1279 | 45 | 36 | 0 | 19 | 10 | 0.9 | 15 | 1.3 | 44 | 259 | 246 | 1.7 | 1.4 | |

| Type | NO. | Name of historic district | Road length (m ) | Network2 (The whole road network) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total length | Main Road (>4 m) | Narrow Street (<4 m) | e | ν | Number of end point | Number of intersection | µ | µa | α (%) | β | γ (%) | Di (m) | Dl (m/ha) | Dc | A | |||

| Type1 | 4 | Shiramine | 3725 | 2418 | 1307 | 169 | 150 | 10 | 47 | 20 | 1.9 | 7 | 1.1 | 38 | 336 | 348 | 4.4 | 1.3 |

| 13 | Iwaishima | 6311 | 2599 | 3711 | 257 | 215 | 13 | 87 | 43 | 2.4 | 10 | 1.2 | 40 | 323 | 355 | 4.9 | 1.4 | |

| 16 | Taketomi Island | 7914 | 4546 | 3368 | 191 | 149 | 5 | 78 | 43 | 1.1 | 15 | 1.3 | 43 | 456 | 207 | 2.0 | 1.2 | |

| 10 | Okikamuro | 2857 | 1565 | 1293 | 105 | 99 | 13 | 28 | 7 | 0.5 | 4 | 1.1 | 36 | 274 | 198 | 1.9 | 1.4 | |

| 11 | The West of Higunto | 5861 | 2854 | 3007 | 245 | 215 | 22 | 75 | 31 | 1.3 | 7 | 1.1 | 38 | 461 | 253 | 3.2 | 1.2 | |

| 12 | The East of Higunto | 7867 | 3965 | 3902 | 311 | 278 | 34 | 102 | 34 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.1 | 38 | 639 | 297 | 3.8 | 1.4 | |

| Type2 | 3 | Kuroshima district | 3993 | 2144 | 1849 | 153 | 127 | 6 | 57 | 27 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.2 | 41 | 281 | 195 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| 5 | Obama-nishigumi | 3656 | 2502 | 1154 | 81 | 68 | 6 | 32 | 14 | 0.7 | 11 | 1.2 | 41 | 339 | 191 | 1.7 | 1.3 | |

| 8 | Mitarai | 4124 | 2236 | 1889 | 177 | 148 | 17 | 65 | 30 | 4.3 | 10 | 1.2 | 40 | 242 | 598 | 9.4 | 1.3 | |

| 9 | Miyajima | 9424 | 7181 | 2243 | 318 | 280 | 12 | 81 | 39 | 1.0 | 7 | 1.1 | 38 | 571 | 240 | 2.1 | 1.4 | |

| Type3 | 1 | Motomachi·Suehirocho | 6572 | 6361 | 212 | 86 | 63 | 6 | 43 | 24 | 1.7 | 20 | 1.4 | 47 | 417 | 453 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| 2 | Makabe | 4608 | 4245 | 363 | 63 | 49 | 4 | 31 | 15 | 0.9 | 16 | 1.3 | 45 | 353 | 262 | 1.8 | 1.3 | |

| 14 | Chikugoyoshii | 6835 | 5207 | 1628 | 143 | 114 | 2 | 57 | 30 | 1.4 | 13 | 1.3 | 43 | 406 | 330 | 2.8 | 1.6 | |

| 15 | Yamefukushima | 5697 | 4428 | 1269 | 96 | 77 | 6 | 41 | 20 | 1.0 | 13 | 1.2 | 43 | 425 | 288 | 2.1 | 1.3 | |

| Type4 | 6 | Imai-cho | 6820 | 4929 | 1891 | 135 | 91 | 0 | 66 | 45 | 2.6 | 25 | 1.5 | 51 | 315 | 392 | 3.8 | 1.7 |

| 7 | Tondabayashi | 4036 | 2757 | 1279 | 96 | 66 | 0 | 43 | 31 | 2.8 | 24 | 1.5 | 50 | 253 | 360 | 3.8 | 1.3 | |

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Cyclomatic number (µ ) and Average Cyclomatic number (µa ). |

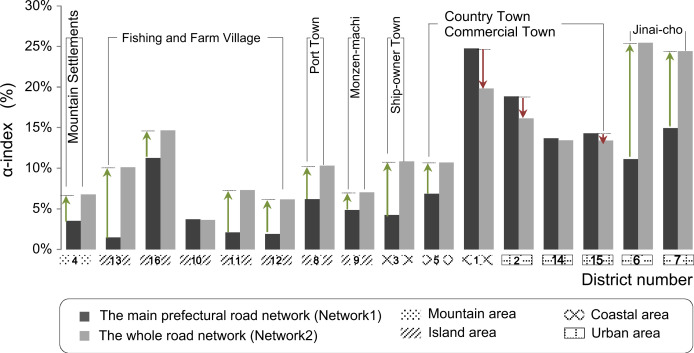

Second, the α indicator values for both the main prefectural road and the entire road network are higher in the historic blocks of cities than in traditional villages (Fig. 5 ). This finding indicates that the road network form of the historic blocks in cities is closer to the “complete link age” type; that is, traffic efficiency is higher when people move in a circular manner. In addition, the change in the values for NW1 and NW2 in the same district is compared, and the values of the historic blocks in all cities decrease, except for those in 6.Imai-cho and 7.Tondabayashi. As per Table 2 , the number of nodes in these districts increases when narrow streets are considered in the analysis of the entire road network. This result suggests that the narrow streets in these districts are mostly impassable, pouch-shaped roads. Therefore, the number of circular roads (μ ) changes less in NW2 than in NW1. The number of nodes and links that form the network increase, thus reducing the α value of the entire road network. With respect to the formation background of the historic blocks, the districts are mostly port and commercial towns; in these areas, roads that are more than 4 m wide were previously used as public spaces and functioned as path ways for transportation and trade. Thus, the roads are interconnected and are complete. Roads that are less than 4 m wide are located in the gap between two housing complexes and are utilized for drainage and residential access. These roads are not responsible for the traffic connections in the overall road network; therefore, the formation of circular roads is difficult in this case.

|

|

|

Fig. 5. α -index. |

On the contrary, 6.Imai-cho and 7.Tondabayashi are “Jinai-cho” towns that were independent settlements formed with temples at the center. The areas surrounding the towns are enclosed by trenches or high walls, and the town is isolated (Horiuchi et al., 2006 ). The road layout is depicted in Fig. 3 . Theintegration of internal transport was emphasized, and the “grid-type” road network form was jointly formed by the roads that were more and less than 4 m wide. Therefore, the number of circular roads is significantly higher in NW2 than inNW1; moreover, the former is more complete in form than the latter. The α value also increases.

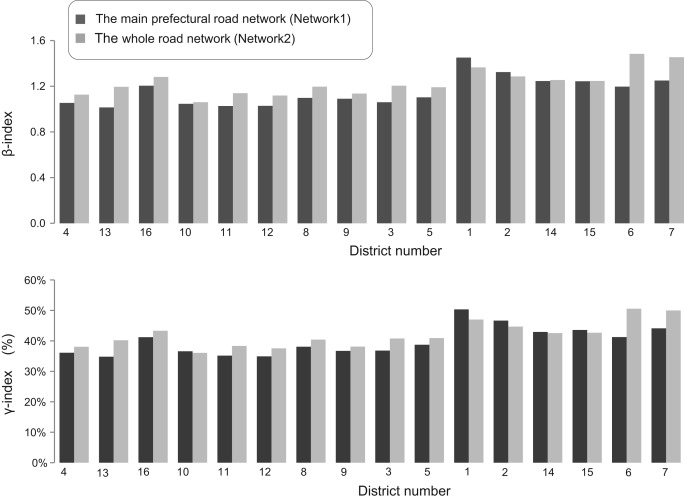

Finally, the road network of each district is evaluated based on the β and γ indicators. As shown in Fig. 2 , the values of β and γ increase with the number of links when the network form is close to the complete linkage type. Therefore, the numbers of nodes and links required for circular network formation can be determined with the β and γ indicators when no intersecting link is detected and the road network forms in the districts are similar. These indicators reflect the road network circularity to a certain extent. The higher the values are, the fewer the nodes and links required for circular road network formation. Moreover, few paths are traversed by ramblers during rambling activities; thus, road network circularity improves. Table 2 shows that in the main prefectural roads (NW1), the value for 1.Motomachi is 1.5; this value is 50.3% higher than that of the other districts. As indicated in Fig. 2 , the road network form in this district is closest to the “grid-type.” Therefore, this district has better circularity than other historic blocks in cities such as 2.Makabe and 7.Tondabayashi. On the contrary, the values of most of the districts in the entire road network (NW2) increase significantly, as displayed in Fig. 6 . Considering the change in road network forms, the narrow old streets in these districts strengthen the connection between the roads and enhance the closeness of the road network form to the complete linkage type. This connection strengthens the circularity in the district.

|

|

|

Fig. 6. β -index and γ -index. |

4.2. Accessibility characteristics

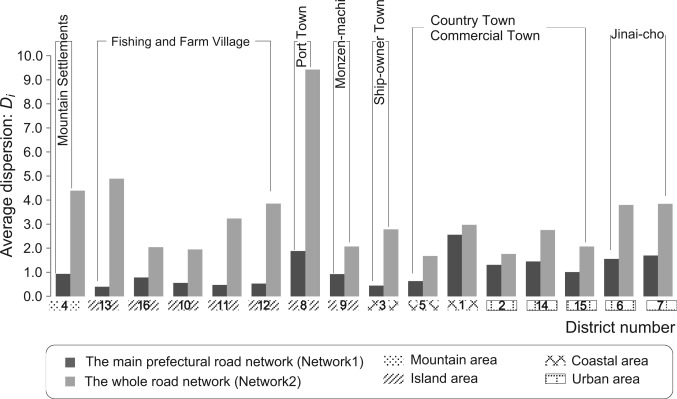

This section describes the evaluation of road network accessibility based on road network density (Dl and Dc ) and the average shortest distance Di between each of the two nodes. First, the road density (Dl ) and node density (Dc ) values for the main prefectural roads in the historic blocks of cities such as 1.Motomachi, 2.Makabe, and 14.Chikugoyoshii are considerably higher than those of the traditional villages. This result suggests that such road networks are dense and large in scale. By contrast, the increase rate of the values for traditional villages is more significant than that for the historic blocks in cities when the effect of narrow streets and of the analysis on the entire road network is considered. This finding reveals that the formation of the road network in traditional villages mainly relies on narrow streets that are less than 4 m wide.

Second, the districts with the highest Di values for the main prefectural roads are 9.Miyajima (738 m), 12.East of Higunto (696 m), and 11.West of Higunto (526 m). This outcome indicates that in these districts, the average distances between the two nodes are great; thus, overall accessibility is poor. When the forms and densities of the road networks in these districts are combined, the main road network formation is sparse and takes the “tree-type form” due to the monotonous connections between the two nodes. Although the area, scale, and node density of the 16.Taketomi Island district are similar to those of 9.Miyajima, the road network form of the former is of the “grid-type”; therefore, the connections among nodes are tight and direct. Hence, accessibility in the district improves. The analysis results of the entire road network suggest that the values for most of the districts decrease, thus indicating that narrow old streets shorten the distances between two nodes of the road network in the districts. This scenario plays a role in enhancing accessibility in the district. As shown in Fig. 7 , the values for traditional villages located on islands decrease significantly. Based on the high Dl and Dc values of the traditional villages in NW2, the dense and complex road network forms composed of narrow streets that are less than 4 m wide as well as the lack of drainage channels linked to the mountain forests and alleys among residential structures play a significant role in the accessibility and traffic convenience in the districts. By contrast, the changes in the values of most of the historic blocks in the cities are unremarkable. This result indicates that the roads less than 4 m wide weakly affect accessibility in these districts. The reasons for this outcome can be deduced by combining the densities and forms of the road networks. First, narrow old streets comprise only a small proportion of the overall road network formations given commercial-type historic blocks in cities such as commercial and port towns. Therefore, these streets exert little influence on the overall road network structures. Second, the road network forms of most of the historical blocks in cities are closer to the grid pattern than those in traditional villages. Given that this form is more stable and the distances between two nodes are close to the minimum distances, narrow streets shorten distance only in certain local road network sunder the condition of preserving this type of road network form. Therefore, these streets exert little influence on the entire road network. As shown in Table 2 , the changes in the Di values of NW1 and NW2 are insignificant although the narrow streets constitute a large proportion of the road network formations in 6.Imai-cho and 7.Tondabayashi.

|

|

|

Fig. 7. Average dispersion (Di ). |

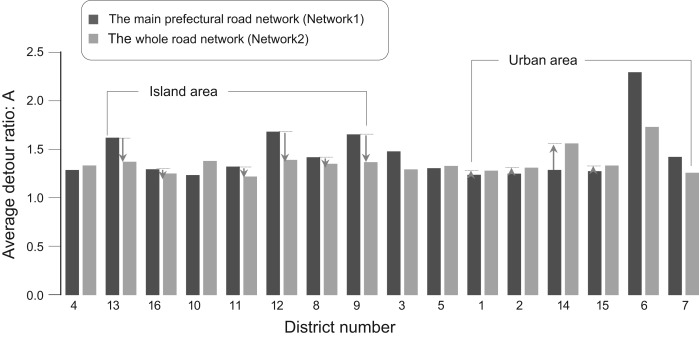

4.3. Indirection characteristics

The detour rate (A ) for 6.Imai-choin NW1 is 2.3; this value is considerably higher than that of the other districts. Thus, the connections among the nodes in this district are weak in the road network consisting of roads that are more than 4 m wide. People on these roads must walk more than twice the linear distance on average to reach a destination point. Therefore, the indirection of the main roads in this district is strong, whereas the extent of traffic convenience is poor. The A values for 13.Iwaishima and 12.Higunto are also high because of their topographic environment. Given that island villages are generally distributed along the bay, are backed by mountains, and stand on tilted terrain, the roads in NW1 mainly assume winding forms; as a result, indirection increases in these districts. As displayed in Fig. 8 , the A values from NW1 to NW2 decrease in most island villages; thus, the narrow streets that are less than 4 m wide strengthen the linear connections among the points in the road network, improve the overall indirection, and enhance traffic efficiency within the district. By contrast, the narrow streets in the historic blocks of the cities in NW2 are primarily impassable, pouch-shaped spaces; therefore, the A value of the overall road network is higher than that of NW1.

|

|

|

Fig. 8. Average detour ratio (A). |

4.4. Clustering analysis

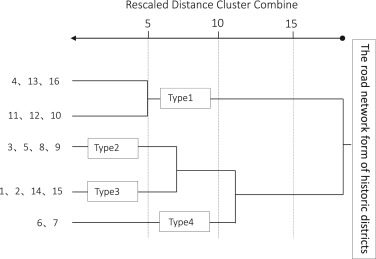

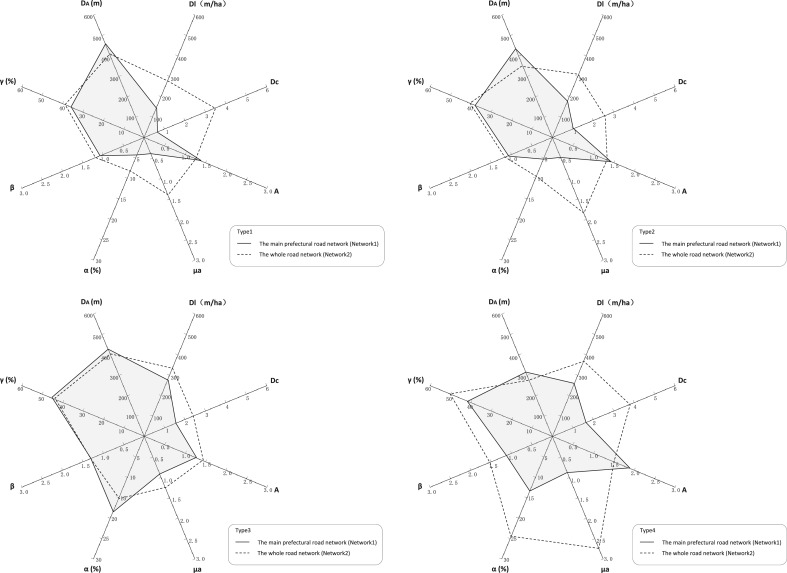

As detailed in the previous sections, the road network of each historic district was quantitatively analyzed in terms of circularity, accessibility, and indirection. To comprehensively understand the spatial form and structure reflected by the aforementioned characteristics, this section discusses the use of the values of the 11 indicators (e , ν , μ , μa , α , β , γ , Di , Dl , Dc , and A ) in NW1 and NW2 as variables in a clustering analysis on the 16 historic districts. The ward method was used, and the values of each indicator were standardized to unify the units of the variables. The results are shown in Fig. 9 . Four types were identified based on the differences in the road network form characteristics of various historic districts. In addition, the characteristics of each type can be clearly recognized and detailed as follows according to the radar chart of the average values of the major variables in each type (Fig. 10 ).

|

|

|

Fig. 9. Similarity of road networks in the research area. |

|

|

|

Fig. 10. The spatial characteristics of each type. |

Type 1 includes traditional villages that are located on islands and in mountain areas. These villages were naturally formed according to the primary industry. The main road networks contain few circular roads, and the road network tends to take the tree-type form; thus, the network exhibits low density, circularity, accessibility, and indirection. In the overall road network that includes narrow old streets, each indicator changes significantly; for instance, circularity and accessibility improve considerably, whereas indirection declines. Therefore, the formation of this type of road network mainly relies on roads that are less than 4 m wide. In terms of α , β , γ , the indirection of the overall road network remains poor across all the districts.

Type 2 includes settlements in the coastal areas and mainland-connected islands. These settlements were developed through ports and religious facilities. In this study, the values of each NW1 indicator are better than those of the traditional villages under Type 1; however, circularity and road network density are low among the investigated subjects. By contrast, circularity, accessibility, and indirection improve in NW2, and the values are within mid-range in general.

Type 3 includes historic districts that were developed by relying on commercial production. The main road network follows the grid pattern form, and the values of each indicator are better than those of the other types. In fact, the circularity, accessibility, and indirection of this type are ideal among all the subjects studied. Nevertheless, the values of the indicators in the overall road network (NW2) that includes narrow old streets hardly vary from those inNW1.Evendetour rate increases, thus indicating that the road networks of this type mainly consist of roads that are more than 4 m wide and stable structures. The narrow streets weakly influence the characteristics of the overall road network form.

Type 4 includes the “Jinai-cho” towns 6.Imai-cho and 7.Tondabayashi. As mentioned previously, the spatial structure of Type 4roads emphasize the traffic connections within the districts because their formation backgrounds differ from those of other districts. Therefore, the overall road network is jointly composed of roads that are more and less than 4 m wide. The analysis results reveal that, the road network forms in NW1 is incomplete because only roads that are over 4 m wide are considered. Thus, the indicators report lower values than those of other historic blocks in the same cities. Moreover, the characteristics of the road network forms are weak. In NW2 (the complete road network form), each indicator improves, and road network circularity increases significantly. In fact, this circularity is the best among all the subjects investigated in this study.

5. Conclusion

This study focused on the well-preserved road network forms of historic districts and analyzed the road spaces of 16 historic districts in Japan in terms of circularity, accessibility, and indirection based on graph theory. This work aimed to systematically clarify the spatial characteristics of the historic road spaces in districts with different formation backgrounds and their corresponding types. This research also endeavored to quantitatively describe the effect of road network formation on spatial characteristics. The main conclusions are presented as follows:

- In traditional villages dominated by agriculture and fishery and are dependent on natural conditions, narrow streets that are less than 4 m wide serve as auxiliary road systems to strengthen the overall connection of the road network. In a road network that functions as traffic connections to external communities and consists of roads that are more than 4 m wide, narrow streets that are less than 4 m wide further subdivide the internal grid of the districts; as a result of the highly elevated road density, the road form becomes dense and complex. Nonetheless, the narrow streets improve the circularity, accessibility, and indirection of the overall road spaces.

- In settlements of port and commercial towns formed for port trade and commercial production purposes, the main frame of the road network is composed of roads that are over 4 m wide. This network displays a complete overall form as well as ideal circularity, accessibility, and indirection. The roads that are less than 4 m wide merely serve as subsidiary spaces; they further dividing some roads in local areas and exert little effect on the spatial characteristics of the overall road network.

- Due to a historical isolated spatial mode, the districts in “Jinai-cho” towns emphasize inward traffic connection. The overall road network in such areas is jointly composed of horizontal roads that are more than 4 m wide and vertical roads that are less than 4 m wide. The removal of any of these portions renders the road network form incomplete and deteriorates road network circularity, accessibility, and indirection. The overall road network tends to take the grid form; thus, the circularity of this district type is higher than that of the remaining historic districts.

References

- Ando et al., 2001 Ando, Y., Zhao, S., Hagishima, S., 2001. A study on the road network forms of former foreign possession in tenshin, china: part 1. Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, pp. 335–336.

- Aoki et al., 2010 S. Aoki, M. Osawa, T. Kishii; On the city planning roads in important preservation districts of traditional buildings; J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn., 45 (3) (2010), pp. 367–372

- Beineke and Wilson, 1978 Lowell W. Beineke, Robin J. Wilson; Selected Topics in Graph Theory; Academic Press, USA (1978)

- Graham et al., 1977 R.L. Graham, A.J. Hoffman, H. Hosoya; On the distance matrix of a directed graph; J. Graph Theory, 1 (1977), pp. 85–88

- Horiuchi et al., 2006 Horiuchi, Y., Watanabe, T., Tsuchiya, T., Fukuta, T., Asano, S., 2006. A Study on the Isshinden-Jinaicho Ring Moat, Tsu city : part 2 the Management Situation of the Composition, Private use Objects, Belonging Objects, Water Conveyance and Drainage of the Ring Moat and the Periphery Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, pp. 1043–1044.

- Iwakuma, 1997 T. Iwakuma; Study on rural land scape planning as viewed from the spatial structure of roads : Planning method developed in Koura-Chou, Shiga prefecture; J. Archit. Plan. Environ. Eng., AIJ, 492 (1997), pp. 143–148

- Kamae et al., 1995 Kamae, H., Enya, T., Rin, S., Matsuura, J., Asano, S., 1995. A study on the classification of historical ways in Mie Pref.: part 3 the classification by the sectional from and the topography condition the land use along the route. Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, 79–80.

- Kawakami et al., 2012 M. Kawakami, Y. Yamashita, H. Kuroi, T. Nishino; Study on planning of residential environment considering townscape preservation in historical congested area : a case study in kanazawa city; J. Archit. Plan., AIJ, 77 (673) (2012), pp. 573–582

- Kozuka et al., 2005 Kozuka, M., Mitera, J., Kawamoto, Y., Honda, Y., 2005. A study on regional maintenance course for making efficient use of the historic highway. Nature and environment of the Sea of Japan districts the memoirs of the Research and Education Center for Regional Environment, University of Fukui, 12, pp. 51–60.

- Koshizuka, 1978 T. Koshizuka; A new method for analyzing road networks; J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn., 103 (1978), pp. 36–41

- Miyashita et al., 2013 T. Miyashita, N. Nakajima, T. Ichinose; A study on changes of evaluations to the street structure as to urban planning in center of Shizuoka city : noticing the consciousness of urban design based on streets; J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn., 48 (3) (2013), pp. 489–494

- Miyawaki, 2012 M. Miyawaki; A study on the historic landscape characterization: historic landscape character assessment of temples, streets, blocks, watercourses, and land use in the central Kamakura; J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn., 47 (3) (2012), pp. 607–612

- Nishiguchi, 2004 Nishiguchi, T., 2004. A study on review of city planning road in historical urban area:Tajimi city, Kashihara city and Kawagoe city in the main Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, pp. 1131–1132.

- Okada and Miyazaki, 2012 Okada, Y., Miyazaki, T., 2012. A study on community formation of the street space in a historical area (1): about the characteristic of street space, and potential relation of a local community. Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. E-2, 1421–1422.

- Punnoi et al., 2010 Punnoi, N., Kubota, A., Suzuki, R., Sakuraba, K., Okuma, M., 2010. Analysis of promoting factors for visitors׳ rambling activities: a study for the improvement of visitors׳ rambling activities in historic area in Sawara (part.1). Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, pp. 557–558.

- Rin et al., 1995 Rin, S., Enya, T., Kamae, H., Matsuura, J., Asano, S., 1995. A study on the classification of historical ways in Mie Pref.: part 1 the frame work of this study and the classification by topography condition. Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, pp. 79–80.

- Sakai and Naya, 1992 H. Sakai, K. Naya; Relationships between α and β -indices for measuring network connectivity and relationships between the development of forest-road networks and these indices ; J. Jpn. For. Soc, 70 (1992), pp. 245–250

- Saito, 2002 Saito, C., 2002. Urban block pattern and effciency of road network: a study on simulation method of block generation by building arrangement. City planning review. Special issue Papers on city planning, 37, pp. 85–90.

- Saito, 2011 Saito, C., 2011. Prediction of buildings emergent position from accessibility, independence and distribution of shortest path between buildings: logistic regression model of buildings arrangement in typical urban block. Papers on city planning, 46(3), pp. 397–402.

- Shimizu and Ono, 2006 Shimizu, H., Ono, H., 2006. Process and significance of improvement plan of narrow streets in Shuri-kinjo district in Naha city. Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. E-2, pp. 625–626.

- Takagi et al., 1991 M. Takagi, H. Taniguchi, J. Kim; Basic study of indexes of graphs and networks and analysis of street structures of underground towns by applying them: studies on an analysis method of trafic lines of architectural planing applying indexes and the theory of graphs and networks part 1; J. Archit. Plan. Environ. Eng., AIJ, 422 (1991), pp. 37–44

- Tamura et al., 2001 Tamura, K., Koshizuka, T., Ohsawa, Y., 2001. Relationship between road distance and euclidean distance on road networks. City planning review. Special issue, Papers on city planning, 36, 877–882.

- Tanaka and Akasaki, 2000 Tanaka, H., Akasaki, K., 2000. A Study on the decisions and revisions on conservation district of traditional buildings and Planned road in TondabayashiJinaimachi: A study on the conficts of historic environment conservation and urban planning. Summaries of technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan. F-1, pp. 1037–1038.

- Watanabe et al., 1983 Watanabe, K., Hara, H., Fujii, A., Yamanaka, T., 1983. Application of graph theory on architectural planning: Part 1 Basic analysis. Technical papers of Annual Meeting Architectural Institute of Japan, 334, pp. 117–127.

- Yamazaki et al., 2013 A. Yamazaki, H. Tamagawa, I. Nakabayashi; The relation of the narrow street arrangement measures and the district feature of the built-up area in a community rearrangement work area: a study on the direction of narrow street arrangement measures and the district characteristic in Tokyo ward (ku)-area; J. Archit. Plan., AIJ, 78 (694) (2013), pp. 2547–2556

Document information

Published on 12/05/17

Submitted on 12/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?