Robotic continuous ultrasonic welding (cUSW) is a promising technique for joining carbon fiber-reinforced thermoplastics (CFR-TP), offering high efficiency and fast processing times. However, maintaining weld quality and process robustness presents significant challenges. The characteristics of the weld, such as joint strength and long-term performance, are heavily influenced by key parameters during both heat generation and consolidation phases.

Understanding the interactions between the robotic system and the ultrasonic welding process is essential, as they directly impact the quality and consistency of the weld. The robot must precisely control the sonotrode’s movement in the heat generation phase to maintain constant force, trajectory accuracy, and speed uniformity, ensuring efficient energy transfer and uniform melting. During consolidation, both speed and force are critical, controlling the heat dissipation to bring the interface temperature below the crystallization point and preventing defects. To address these challenges, real-time monitoring of key process parameters is essential. Advanced sensor integration and data-driven control strategies enable dynamic adjustments to optimize welding conditions and prevent defects.

This paper explores the challenges associated with robotic continuous ultrasonic welding of CFR-TP and discusses monitoring techniques and control strategies to enhance weld consistency and process reliability.

Keywords: continuous ultrasonic welding, thermoplastic composites, in-situ monitoring, controlling

- '1.' Introduction

With growing concerns about sustainability and the demand for higher production rates, the aviation industry is increasingly exploring the use of thermoplastic composites. These materials offer weldable and reformable characteristics, making them well-suited for ultrasonic welding (USW), which is a promising alternative to conventional mechanical fastening methods [1]. Unlike mechanical fastening, which leads to drawbacks such as fiber breakage, stress concentrations, increased weight, and reduced structural performance, USW enables a lightweight design and efficient joining solution.

USW is a fusion bonding technique that generates heat at the interface through high-frequency (20–40 kHz) and low-amplitude (50–100 µm peak-to-peak) vibrations during the heating phase [2]. To concentrate the vibrational energy at the interface, resin-rich features called Energy Directors, ED, are placed between the adherends [3]. The ED is usually made up of the same thermoplastic material as that in the composite. After the vibration phase, the molten matrix at the interface is allowed to cool down below its glass transition temperature ( ) during the consolidation phase.

The high heating rate of USW is a result of a combination of surface friction and viscoelastic heating. At the beginning of the vibration phase, the process is dominated by interfacial frictional heating, which is strongly influenced by the welding force and relative displacement between the ED and the adherends [4]. The relative displacement is a result of the cyclic deformation of ED due to the vibrational amplitude. It is also important to understand that the normal stress ( ) applied on the interface consists of two parts: a static term, which is applied by an actuator (sonotrode), and a dynamic term, which is generated by the vibrations during welding. Levy et al. have demonstrated that the dynamic term ( ) significantly exceeds the static term ( ) in magnitude [5].

|

|

(1) |

When the sonotrode’s base uniformly overlaps with the top adherend, the static pressure can be calculated as shown in Eq. (2), where is the static force applied and A is the area of the overlap under the sonotrode.

|

|

(2) |

As the temperature reaches the , the thermoplastic matrix at the interface exhibits both elastic and viscous behaviours. Viscoelastic heating then becomes the dominant heat generation mechanism where the heating rate, Eq. (3), is directly proportional to the cyclic strain in the ED due to the vibrational amplitude , loss modulus of the resin ( and vibration frequency (𝜔) [6].

|

(3) |

Welding force, amplitude, and frequency are critical parameters that govern the heating mechanisms in the process. Therefore, ensuring the consistency of these parameters, along with proper sonotrode alignment and position, is key to a successful weld.

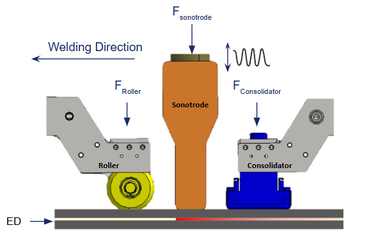

As depicted in Fig. 1, Continuous Ultrasonic Welding (cUSW) efficiently joins materials by using a continuously vibrating sonotrode that moves along an overlap, generating a molten interface [7]. A roller first applies a pre-clamping force to the adherends. Then, the vibrating sonotrode applies pressure, followed immediately by a consolidation block that maintains the pressure until the weld cools down sufficiently. In this process, the speed of the tool or end effector governs the amount of heating and cooling time of the weld, which makes it an equally important parameter as mentioned above.

To meet the high production demands of the aviation industry and facilitate the welding of long, complex joints, robotic systems are essential for both spot and continuous welding. They make the welding process agile by their ability to automate a vast range of intricate motion paths with efficiency. However, industrial robots with serial kinematics often struggle with absolute accuracy, particularly under high applied forces, due to their low stiffness. Therefore, a robotic continuous ultrasonic welding process involves challenges associated with significant robot and process interactions. Understanding these interactions and the implementation of suitable compensation strategies are key to ensuring a robust welding process. The initial section of this paper details the challenges arising from these interactions. Following this, the second section focuses on the strategies developed to overcome these challenges and increase the robustness of the process. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the key findings and discusses the potential future decisions.

- '2.' Challenges

- '2.1.' Path Deviations and Misalignments

Industrial robots lack sufficient absolute accuracy, especially when subjected to the high static and dynamic forces characteristic of ultrasonic welding processes. This limitation arises primarily due to the inherently lower structural stiffness of industrial robots. Contributing factors include joint compliance, flexible links, transmission backlash, joint friction, and varying environmental influences such as temperature [8]. Furthermore, the end effector is also not a rigid body with very high stiffness, which affects the performance of the process. The high forces generated by the sonotrode and consolidator in cUSW, often exceeding several kilonewtons, lead to deflections in the robot and end-effector. Such deflections not only cause deviations from the intended weld path but also lead to misalignment of the sonotrode. For optimal energy transfer, the sonotrode must maintain a perpendicular orientation to the surface of the top adherend. However, angular misalignments result in non-uniform contact with the top adherend and restrict the even distribution of applied force. These issues directly impact the efficiency of vibration transmission and can significantly degrade the weld quality [9]. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the observed path deviations in the Y direction, 90 degrees to the weld line, and rotational measurements around the X and Y axes of the end effector during the welding process.

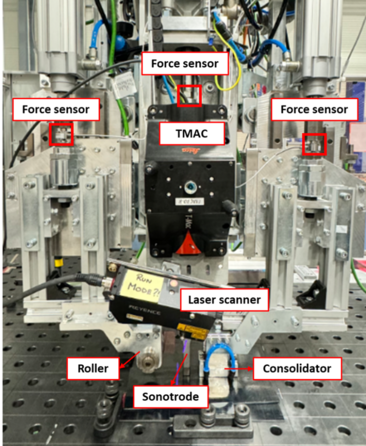

These measurements were obtained using a laser tracker from Hexagon in combination with a T-Mac, sensor capable of 6D measurements, mounted on the end effector, as shown in Fig. 2. The perpendicular alignment of the sonotrode to the top adherend was ensured via the measurements conducted using reflectors and a laser tracker before welding. As shown in Fig. 4, the rotational deviations observed during welding were minimal, suggesting that the force distribution across the contact surface was relatively uniform. However, it is important to note that these measurements reflect the orientation of the end effector, not the sonotrode itself. In practice, sonotrode misalignments may still occur, particularly at points along the weld path where frictional forces are high. Since there is currently no method available to directly measure the orientation or angular deviations of the sonotrode during welding, such misalignments can only be inferred indirectly, posing a limitation for precise in-situ evaluation of sonotrode alignment.

- '2.2.' Force Deviations

As mentioned above, welding and the consolidation forces are important parameters that require not only careful selection but also to be contained within the allowable window. This is also valid for the pre-clamping force applied by the roller since it affects the boundary conditions of the heat-affected zone. The forces are applied using pneumatic cylinders, pressures in which are regulated via proportional pressure regulators and maintained at to set point. However, for a more accurate monitoring of the forces, force sensors from Burster GmbH were integrated between the piston rod and the components, as shown in Fig. 2, to observe the deviations in the forces during welding (if any) and the effectiveness of the built-in pressure regulation.

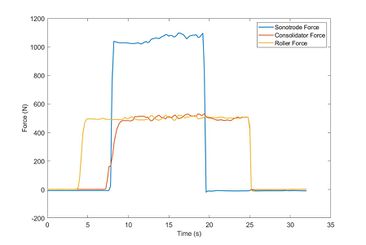

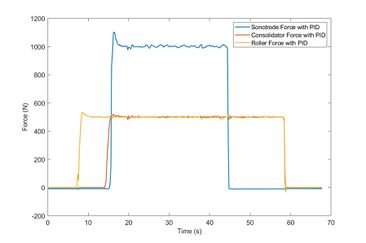

Fig.5 shows the measured force values during the welding process. The set values for the sonotrode, roller and the consolidator were 1000N, 500N and 500N, respectively. The data shows that the measured forces deviated from the set point during the process, especially in the case of the sonotrode (> 7%). Such deviations are not desirable for achieving a consistent weld quality. In addition to this, a fluctuation in the force values in one component was seen when other components were activated or deactivated on the adherend. Such effects are linked to the low stiffness of the end effector, where the change in forces also plays a role in the tilting of the end effector. Therefore, these momentary effects of force application and removal need to be corrected quickly, in addition to ensuring accuracy in the applied force during the welding process.

2.3. Speed Deviations

A correct and stable speed of the components at the end effector ensures consistent heating under the sonotrode and cooling under the consolidator, leading to uniform welds. To monitor this, the robot’s speed was tracked using a Robot Sensor Interface (RSI) program integrated into the robot’s welding program. Within the RSI program, velocity values were computed every 4 ms based on changes in the X and Y positions of the Tool Center Point (TCP), which in this case corresponds to the sonotrode.

Despite the robot being programmed for a constant welding speed, noticeable acceleration and deceleration phases were observed during the welding process. These variations are attributed to the high contact forces generated as the sonotrode and consolidator slide over the surface of the top adherend. The resulting frictional forces trigger the stick-slip effect, a phenomenon where motion alternates between sticking and slipping due to the difference between static and kinetic friction. The stick-slip behavior arises because static friction, which resists initial motion, is greater than kinetic friction, which governs motion once sliding begins. Initially, static friction resists motion until the applied force exceeds a threshold, triggering kinetic friction and a sudden acceleration beyond the set speed. As resistance builds, the system slows, static friction returns, and velocity drops below the target. These cycles repeat, especially when system stiffness is insufficient [10]. The stiffness of the combined robot and end effector structure plays a crucial role in this behavior. Lower stiffness leads to greater compliance, resulting in elastic deformation and amplification of stick-slip dynamics. This inconsistent velocity can lead to inconsistent heat generation and consolidation along the weld line, leading to inhomogeneous weld quality with potential defects.

Figures 6 and 7 present the measured speed during dry run and welding conditions, respectively, when all components were already actuated and moved on the top adherend, with the target welding speed set to 12 mm/s. The applied forces for the sonotrode, consolidator, and roller were 1000 N, 1000 N, and 500 N, respectively. Due to the low stiffness of the robot and the end effector, the positions taken from the robot’s controller varied from the real pose information of the sonotrode. Even though the RSI program indicated the constant movement of the robot at the set velocity along the weld line, the actual measured velocity via the laser tracker and T-Mac exhibited significant fluctuations. Due to the presence of additional dynamic forces during welding, speed deviations are greater compared to the dry run, where only static forces are involved in the absence of vibrations.

- 3. Strategies

To overcome challenges in continuous ultrasonic welding and meet the strict tolerances required in the aviation industry, a robust and reliable process is essential. Consistent, high-quality welds must be achieved for workpieces of various shapes and geometries. Selecting the suitable process parameters is essential, but it is not sufficient on its own. Continuous monitoring is necessary to ensure that parameters remain within the allowable range and that deviations between set and actual values are minimized, especially when the process is performed using industrial robots with low absolute accuracy. This can be accomplished through continuous monitoring with advanced sensors capable of keeping up with the fast and dynamic nature of cUSW. These sensors detect deviations from intended values in real-time, allowing for immediate corrective actions when tolerances are exceeded. By integrating such monitoring systems, the welding process remains stable, ensuring repeatability and optimal weld quality.

- '3.1.' In-line Pose Correction and Path-Planning

As mentioned in the previous section, the robot’s absolute inaccuracies and the forces involved in the process cause deflections in both the robot and the end effector, leading to deviations from the desired path and misalignments. Therefore, it is essential to develop a compensation strategy to correct any deviations in the sonotrode’s position along the Y axis and its orientation relative to the top workpiece. To meet the demands of the highly dynamic robotic ultrasonic welding process, a fast-response sensor system is essential. For this purpose, a 2D laser scanner from Keyence was integrated into the end effector, as shown in Fig. 2. The scanner captures edge position data every 12 ms and transmits it to the RSI. At each sampling interval, the position and orientation of a target point on the weld path are measured. The deviation between the actual and desired pose of the sonotrode is calculated to generate an error signal. This signal is then fed into the robot controller, which adjusts the sonotrode’s pose accordingly. The correction is updated every 12 ms to maintain accurate tracking of the weld path. The implemented compensation strategy consisted of two RSI Programs. In the first programme (RSI-I), the laser scanner identified the initial weld point along the edge and determined the orientation of the top adherend. Based on this information, the sonotrode was positioned and aligned perpendicularly to the adherend’s surface. In the second programme (RSI-II), after the application of the necessary contact forces, the sonotrode followed the weld path perpendicular to the top adherend while compensating for real-time deviations using a proportional-integral (PI) controller. The results are illustrated in the figures 8 and 9. The only information that was given to the robot was the length of the weld line in the X direction.

- '3.2.' In-Situ Monitoring and Control of Forces

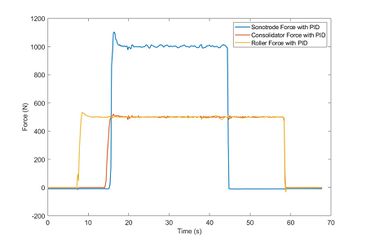

As previously mentioned, welding and consolidation forces are critical parameters that influence heat generation and cooling rates at the interface. Therefore, deviations in these forces must remain within an acceptable range. As shown in Fig. 2, the mounted force sensors continuously transmit force data to the Siemens controller system, facilitating real-time communication and analysis. By implementing a closed-loop PID control, the system automatically compensates for any deviations from the target force every 4 ms. This rapid adjustment mechanism ensures that the applied force remains stable and consistent throughout the process. Fig. 10 shows the measured forces during welding with PID control. Force deviations, as well as the effects of component activation and deactivation, were minimized.

- 3.3. In-Situ Monitoring and Control of Speed

The robot's speed, being a critical process parameter, must be continuously monitored throughout the operation, and strategies should be explored to minimize any deviations from the target velocity. In the KUKA KR500, each joint is driven by a dedicated AC servomotor, forming a multi-axis articulated system. The robot is equipped with an internal closed-loop control system that continuously monitors velocity data from encoders mounted on the motor shafts. This system calculates any deviations from the desired values and sends compensation signals to the AC servomotors, ensuring the required current is applied to achieve the target performance. However, this internal control loop can only compensate for internal deviations. It is not capable of correcting disturbances caused by external factors. As illustrated in Figures 6 and 7, while the Robot Sensor Interface values indicated that the robot maintained the set velocity, actual speed measurements revealed that coincidental external disturbances result in speed fluctuations. To minimize deviations, implementing external velocity control for the robot is not practical in the case of sudden changes. External systems typically respond slowly to abrupt variations and may even interfere with the robot's internal control loops. Sudden changes in velocity could result in high jerks, which in turn cause vibrations and overall system instability. Given that external control is not a feasible solution, alternative approaches must be explored to reduce these deviations. This requires a thorough investigation to identify the root cause of the error.

To address this, a series of experiments were conducted to analyze and understand the underlying issues. The first step involved developing an interface that enables real-time monitoring of the robot's speed. For this purpose, the T-Mac and the Laser Tracker were used to capture the precise pose data of the end effector. The 6D discrete data was recorded using SpatialAnalyzer software. A C++ program was then developed in Visual Studio to receive the data stream from SpatialAnalyzer and perform the necessary velocity calculations. Subsequent experiments were carried out by implementing the TMAC on Axis 6 of the robot to investigate the contribution of the robot to the speed fluctuations happening during the process. As shown in Fig. 11, it was found that the velocity deviations originating from the robot itself were minimal and closely match the data recorded via the RSI, indicating that the robot’s motion control is not a major source of fluctuation and the robot itself is stiff enough. Therefore, the stick-slip effect is primarily triggered by the relatively low stiffness of the end effector. It is important to note that these experiments were carried out when the activation and deactivation of the components also took place during the process, which can be seen in the form of peaks in the data. The first peak refers to the activation of the consolidator, and the second peak refers to the deactivation of the roller. To mitigate such speed fluctuations, the design of the end effector must be optimized for enhanced stiffness. Strengthening the end effector structure will help minimize compliance, reduce velocity fluctuations, and improve overall process stability during welding. In addition, redesigning certain components of the end effector should be considered to reduce friction during the welding process. Since the roller generates minimal friction due to its rolling motion and the sonotrode is a precisely tuned component in terms of geometry, material, and dynamic behavior that cannot be freely altered without compromising its performance, attention must be directed toward the consolidator. By optimizing the design of the consolidator to reduce sliding resistance, overall friction can be minimized, leading to more consistent robot speed and improved weld quality.

These findings offer important insights into the sources of resistance within the overall system, which directly impact speed stability during the welding process and highlight the need for component redesign in the next development phase.

- '4.' Conclusion

The development of a robust robotic continuous ultrasonic welding (cUSW) process is intrinsically linked to understanding and effectively addressing the complex interactions between the robotic system and the welding process itself. These interactions introduce several critical challenges that can significantly hinder the achievement of consistent weld quality. Specifically, the key issues identified include path deviations and sonotrode misalignment due to the low absolute accuracy and stiffness of industrial robots under high forces, as well as undesirable fluctuations in applied forces and welding speed. These deviations directly impact the efficiency of vibration transmission, uniform force distribution, consistent heating, and cooling, ultimately leading to inhomogeneous weld quality and potential defects. From an automation perspective, in-situ monitoring and real-time control strategies offer effective solutions for minimizing the impact of these challenges. As demonstrated, continuous monitoring of the end effector's path and orientation, combined with in-line pose correction via fast-response sensor systems and PI controllers, can significantly reduce deviations and ensure perpendicular sonotrode alignment. Similarly, integrating the force sensors and implementing closed-loop PID control for process forces effectively minimizes force deviations and the undesirable effects of component activation and deactivation. However, effectively minimizing the impact of the stick-slip effect, which primarily arises from the relatively low stiffness of the end effector, requires a different approach beyond external velocity control. The investigation revealed that while the robot's internal motion control is robust, the end effector's design is the primary contributor to these speed fluctuations. Therefore, future efforts must focus on optimizing the end effector's design for enhanced stiffness and actively redesigning certain components, particularly the consolidator, to reduce sliding resistance and overall friction during the welding process.

This research is funded by dtec.bw – Digitalization and Technology Research Center of the Bundeswehr within the project “LaiLa - Laboratory for intelligent lightweight production”. We would like to thank the Composite Technology Center / CTC GmbH (An Airbus Company) for supporting this work.

[1] G. Gardner, “Welding Thermoplastic Composites,” Composites World, https://www.compositesworld.com/articles/welding-thermoplastic-composites (accessed Apr. 22, 2025).

[2] I. F. Villegas, “Ultrasonic welding of thermoplastic composites,” Front. Mater., vol. 6, p. 291, 2019.

[3] B. Jongbloed, J. Teuwen, G. Palardy, I. Fernandez Villegas, and R. Benedictus, “Continuous ultrasonic welding of thermoplastic composites: Enhancing the weld uniformity by changing the energy director,” J. Compos. Mater., vol. 54, no. 15, pp. 2023–2035, 2020.

[4] I. F. Villegas, “In situ monitoring of ultrasonic welding of thermoplastic composites through power and displacement data,” J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 66–85, 2015.

[5] A. Levy, I. F. Villegas, and S. Le Corre, “Ultrasonic welding of thermoplastic composites: Modeling the heating phenomena,” in Proc. 19th Int. Conf. Compos. Mater., Montreal, Canada, vol. 28, 2013.

[6] A. Benatar and T. G. Gutowski, "Ultrasonic welding of PEEK graphite APC-2 composites," Polym. Eng. Sci., vol. 29, no. 23, pp. 1705–1721, Dec. 1989. doi: 10.1002/pen.760292313.

[7] F. Senders, M. van Beurden, G. Palardy, and I. F. Villegas, "Zero flow: A novel approach to continuous ultrasonic welding of CF/PPS thermoplastic composite plates," Adv. Manuf. Polym. Compos. Sci., vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 83–92, 2016. doi: 10.1080/20550340.2016.1253968.

[8] K. Wu, J. Li, H. Zhao und Y. Zhong, "Review of Industrial Robot Stiffness Identification and Modelling, " Appl. Sci., vol. 12, 2022.

[9] M. Ahanpanjeh, F. Köhler, V. Adomat, C. Kober, and M. Fette, "Impact of alignment of the sonotrode on the quality of thermoplastic composite joints in continuous ultrasonic welding," in Proc. SAMPE Eur. Conf., Hamburg, Germany, 2022.

[10] A. D. Berman, W. A. Ducker, and J. N. Israelachvili, "Origin and characterization of different stick-slip friction mechanisms," Langmuir, vol. 12, no. 19, pp. 4559–4563, 1996.

Document information

Published on 30/07/25

Accepted on 20/07/25

Submitted on 16/05/25

Volume 09 - Comunicaciones MatComp25 (2025), Issue Núm. 1 - Fabricación y Aplicaciones Industriales, 2025

DOI: 10.23967/r.matcomp.2025.09.06

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?