| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

* '''Results''' ( [[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_5527_Icon_Results.png|20px]]). Options to visualize the SWMM and Iber results. | * '''Results''' ( [[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_5527_Icon_Results.png|20px]]). Options to visualize the SWMM and Iber results. | ||

* '''Check project''' ( [[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_2183_Icon_Iber.png|20px]]). Dialog that starts a check project. | * '''Check project''' ( [[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_2183_Icon_Iber.png|20px]]). Dialog that starts a check project. | ||

| + | |||

Additionally, the '''Processing Toolbox''' will show two specific option for IberGIS plugin (Fig. 1d). '''Processing Toolbox >> IberGIS''' is related to automatize general procedures such as project checking, import necessary features (ground, roof, inlets layers), import results, and associate Iber inlets/roofs to SWMM junctions. The other one, accessible though ''''Processing Toolbox >> IberGIS – Mesh''', is a pack of particular options to obtain a well-conditioned calculation mesh. | Additionally, the '''Processing Toolbox''' will show two specific option for IberGIS plugin (Fig. 1d). '''Processing Toolbox >> IberGIS''' is related to automatize general procedures such as project checking, import necessary features (ground, roof, inlets layers), import results, and associate Iber inlets/roofs to SWMM junctions. The other one, accessible though ''''Processing Toolbox >> IberGIS – Mesh''', is a pack of particular options to obtain a well-conditioned calculation mesh. | ||

| Line 108: | Line 109: | ||

** Weir (layer of lines) | ** Weir (layer of lines) | ||

** Outlet (layer of lines) | ** Outlet (layer of lines) | ||

| + | * IBER | ||

| + | ** Inlet (layer of points) | ||

| + | ** Hyetograph (layer of points) | ||

| + | ** Boundary conditions (layer of lines) | ||

| + | ** Bridge (layer of lines) | ||

| + | ** Culvert (layer of lines) | ||

| + | ** Pinlet (layer of surfaces) | ||

| + | ** Landuses (layer of dataset) | ||

| + | * MESH | ||

| + | ** Mesh anchor points (layer of points) | ||

| + | ** Mesh anchor lines (layer of lines) | ||

| + | ** Roof (layer of surfaces) | ||

| + | ** Ground (layer of surfaces) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The generation of '''this group of layers''' is automatic during the models creation. It '''can be edit manually''', using the available tools of QGIS, '''or automatically''', using the tools of IberGIS developed ad-hoc (Fig. 1d). Thus, a manual edition requires the generation of the geometric entities of some layer of INPUT group. I.e., if the user wants to simulate only a SWMM model, the proper layer must contain all the information together with the IBER and MESH data. Whereas, an Iber model, without sewer network, requires the definition of, at least, Ground and Boundary conditions layers. Roof layer is optional and when exists it can be linked directly to the Ground or to the Junction layer (if an Iber-SWMM model is simulated). In this sense, an Iber-SWMM model, i.e., a coupled urban drainage simulation, also requires the definition of the Inlet layer and, if there is no flow, the definition of the rainfall data, whether it is by hyetographs or rasters of rain. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It is worth noticing that raster data as topography or infiltration losses can be added to any layer’s group. During the Mesh generation process ( [[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_1076_Icon_Mesh.png|20px]]) these data, if exists in the project, can be selected. Other raster data, such as rainfall raster, must be defined as a timeseries ([[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_8317_Icon_TS.png|20px]]) by defining the raster name per each time interval. The directory where the raster are located must be provided. | ||

| + | Previous to the simulation process ([[File:Sanz-Ramos_et_al_2025a_6615_Icon_Run.png|20px]]), a new folder will be created containing the files that calculation engine Iber-SWMM will be used to carry out the simulation, even save the results. As each simulation scenario can be saved independently, different folders will be created. Note if you share the model (*.gpkg and/or *.gps), the folder that contains the results will be lost. So, the model must be re-simulated to generate again the results or consider to share all this information together with the model. | ||

Revision as of 15:52, 30 October 2025

Abstract

Urban drainage systems are facing increasing challenges due to climate change, urban growth, and the need for more sustainable water management. To address these issues, the Digital DRAIN project has developed an open-source tool that integrates different models within a GIS environment to analyse the performance of drainage systems. The tool helps assess both water flows and pollution, while also supporting the design of sustainable solutions and adaptation strategies. Delivered as the QGIS plugin IberGIS, it provides an accessible framework to improve urban water management and enhance resilience against floods and environmental impacts.

Keywords: urban drainage, 1D/2D modelling, Iber-SWMM, QGIS

Resumen

Los sistemas de drenaje urbano se enfrentan a retos cada vez mayores debido al cambio climático, el crecimiento urbano y la necesidad de una gestión del agua más sostenible. Para abordar estos problemas, el proyecto Digital DRAIN ha desarrollado una herramienta de código abierto que integra diversos modelos en un entorno SIG para analizar el rendimiento de los sistemas de drenaje. Esta herramienta permite evaluar tanto el caudal como la contaminación del agua, además de facilitar el diseño de soluciones sostenibles y estrategias de adaptación. Implementada como complemento de QGIS, IberGIS ofrece un marco accesible para mejorar la gestión del agua urbana y aumentar la resiliencia ante inundaciones e impactos ambientales.

Palabras clave: drenaje urbano, simulación 1D/2D, Iber-SWMM, QGIS

1 Introduction

In recent years, the planning, design, construction, and management of urban drainage elements has evolved towards an integrated approach, known as dual drainage. This process focuses on the joint understanding of all physical processes involved, both in terms of water quantity and quality, as well as surface and sewer network flows, and the final receiving environment (rivers, estuaries, seas, and oceans). This requires modelling and analysis tools that account for such coupling (dual drainage). Furthermore, these tools must address today’s global challenges, moving towards a more sustainable world, improving the ecological status of the environment, incorporating climate change adaptation strategies, and ensuring public safety in the face of natural phenomena such as floods.

Along these lines, the project entitled ‘Digital DRAIN. An Integrated Urban Drainage Model’ (DRAIN, CPP2021-008756) aims to develop an open-source, free modelling tool for analysing all processes of urban drainage, integrated within a graphical information system (GIS) environment. Its purpose is to assess hydraulic performance and the effects of diffuse pollution both on the surface, within the drainage network, and in the receiving environment. The tool will also include specific modules for the implementation of Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SuDS) and for analysing actions related to climate change adaptation.

The project derived in a plugin of QGIS, called IberGIS. This plugin is a full integration of the one-dimensional urban drainage software SWMM and a integration of the two-dimensional hydrodynamic software Iber, particularly its calculation module Iber-SWMM [1]. Thus, not all capabilities neither calculation modules of Iber are available. Only particular characteristics of the Iber-SWMM module are described below.

Data

Data to build-up the models presented in this document is stored here.

Important note

This document does not attempt to be a QGIS manual. Despite the whole model’s build-up process is properly defined, the input data might require a pre-process and previous knowledge in GIS environments. The authors encourage users to familiarise with QGIS by reading the documentation and, in case of general doubts, by contacting to the community.

2 Graphical user interface of IberGIS

2.1 Generalities

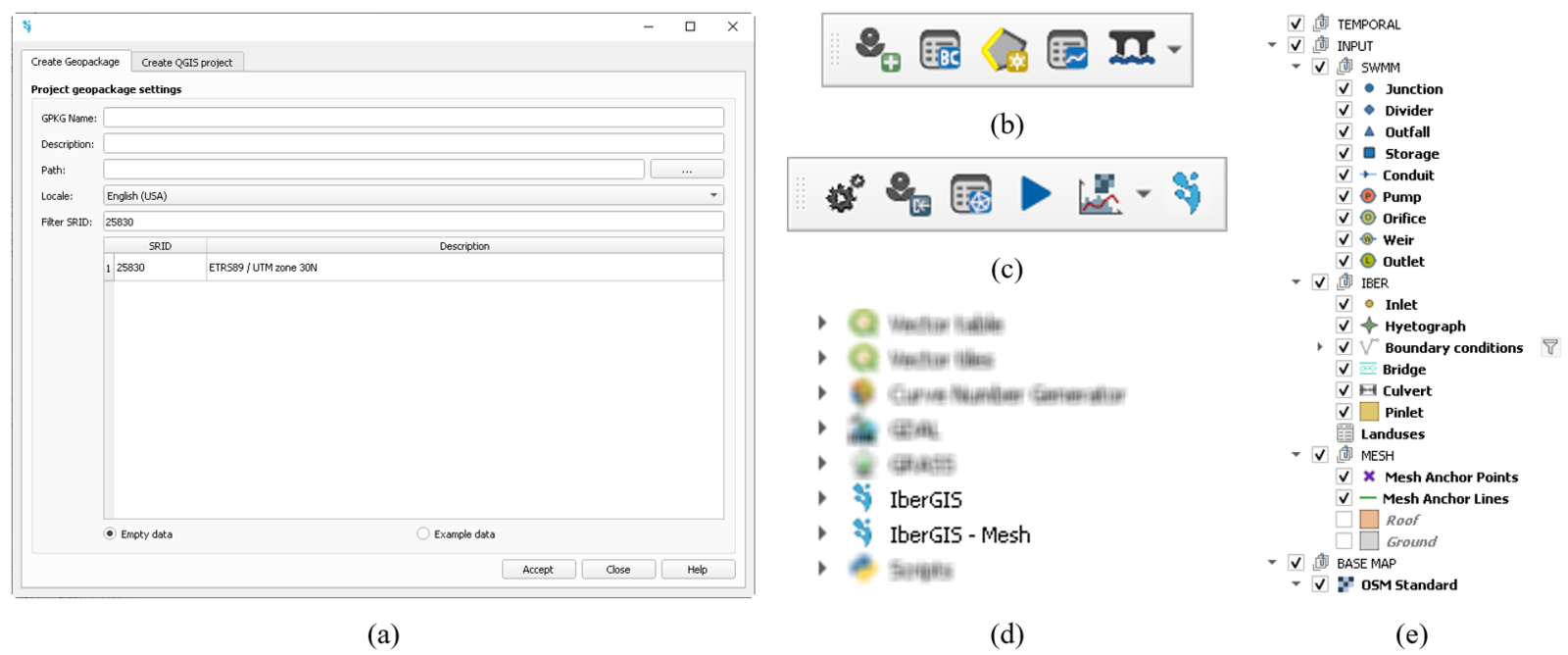

The graphical user interface (GUI) of the plugin IberGIS has been developed within the QGIS environment, and it follows the visual style guide. As for any plugin of QGIS, IberGIS can be installed through Plugins >> Manage and Install Plugins menu. Type “IberGIS” to search it and then click on Install Plugin button. Once installed, and according to the User’s Profile, it will be loaded automatically during the QGIS initialization.

2.2 Particularities

2.2.1 Model structure

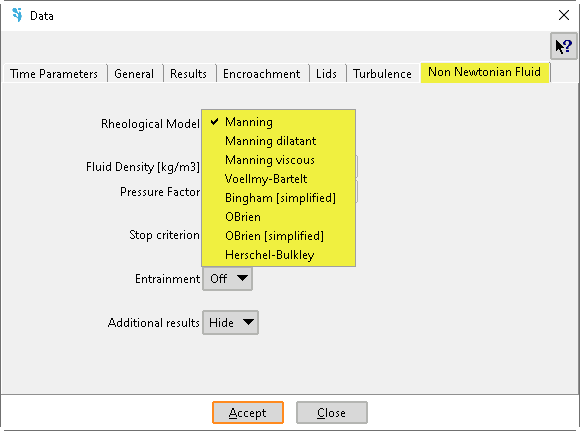

The IberGIS has a workflow fully integrated in the QGIS software. Once installed, the IberGIS button ( ![]() ) will automatically appear in the toolbars of QGIS. Clicking there, a new window will ask for the geopackage and QGIS project creation (Fig. 1a).

) will automatically appear in the toolbars of QGIS. Clicking there, a new window will ask for the geopackage and QGIS project creation (Fig. 1a).

After that, two new groups of toolbars of IberGIS will appear. One is related to the model’s build-up process (Fig. 1b) and the other to the model’s configuration, checks, run the simulation and visualize the results (Fig. 1c). A brief description of each option is detailed below:

- Import INP (

). Imports the *.inp and *.ini files of any SWMM model.

). Imports the *.inp and *.ini files of any SWMM model. - Boundary conditions manager (

). Window that enables saving different boundary condition scenarios.

). Window that enables saving different boundary condition scenarios. - Create boundary condition (

). It automatizes the implementation of boundary conditions.

). It automatizes the implementation of boundary conditions. - Non visual objects manager (

). Window that enables saving different non visual objects, such as timeseries, rules, etc.

). Window that enables saving different non visual objects, such as timeseries, rules, etc. - Bridges actions (

). Options to implement and edit bridges.

). Options to implement and edit bridges. - Options (

). Main model options window.

). Main model options window. - Generate INP (

). Exports the current SWMM layers to a SWMM project.

). Exports the current SWMM layers to a SWMM project. - Mesh manager (

). Window that enables saving different calculation mesh scenarios.

). Window that enables saving different calculation mesh scenarios. - Execute model (

). Window that enables defining general options, selecting the calculation mesh and launch the simulation.

). Window that enables defining general options, selecting the calculation mesh and launch the simulation. - Results (

). Options to visualize the SWMM and Iber results.

). Options to visualize the SWMM and Iber results. - Check project (

). Dialog that starts a check project.

). Dialog that starts a check project.

Additionally, the Processing Toolbox will show two specific option for IberGIS plugin (Fig. 1d). Processing Toolbox >> IberGIS is related to automatize general procedures such as project checking, import necessary features (ground, roof, inlets layers), import results, and associate Iber inlets/roofs to SWMM junctions. The other one, accessible though 'Processing Toolbox >> IberGIS – Mesh, is a pack of particular options to obtain a well-conditioned calculation mesh.

] ]

|

Fig. 1. IberGIS workflow: (a) geopackage and project creation window; (b) build-up processing toolbar; (c) other options toolbar; (d) processing toolbox of IberGIS; (e) layers structure.

Note that any IberGIS model is saved in two files: a geopackage and the QGIS project. Both are linked and when the user opens the QGIS project, automatically it will look for the geopackage. Additionally, the geopackage contains the model itself, so the user can share it without the QGIS project.

2.2.2 Workflow

All this options and functionalities are oriented to facilitate the model build-up process. Since the model is saved in a unique geopackage, different kind of entities can be saved on it. On one hand, non-visual objects is managed in the abovementioned option ( ![]() ). On the other hand, the creation and edition of visual objects is based on a strict group of layers (Fig. 1e) that contains TEMPORAL information (e.g., meshes, results), INPUT data (e.g., data of SWMM and Iber models) and a BASE MAP image. It is mandatory to preserve the structure of the INPUT group, since other data saved in different layers will be omitted during the calculation process:

). On the other hand, the creation and edition of visual objects is based on a strict group of layers (Fig. 1e) that contains TEMPORAL information (e.g., meshes, results), INPUT data (e.g., data of SWMM and Iber models) and a BASE MAP image. It is mandatory to preserve the structure of the INPUT group, since other data saved in different layers will be omitted during the calculation process:

INPUT

- SWMM

- Junction (layer of points)

- Junction (layer of points)

- Divider (layer of points)

- Outfall (layer of points)

- Storage (layer of points)

- Conduit (layer of lines)

- Pump (layer of lines)

- Orifice (layer of lines)

- Weir (layer of lines)

- Outlet (layer of lines)

- IBER

- Inlet (layer of points)

- Hyetograph (layer of points)

- Boundary conditions (layer of lines)

- Bridge (layer of lines)

- Culvert (layer of lines)

- Pinlet (layer of surfaces)

- Landuses (layer of dataset)

- MESH

- Mesh anchor points (layer of points)

- Mesh anchor lines (layer of lines)

- Roof (layer of surfaces)

- Ground (layer of surfaces)

The generation of this group of layers is automatic during the models creation. It can be edit manually, using the available tools of QGIS, or automatically, using the tools of IberGIS developed ad-hoc (Fig. 1d). Thus, a manual edition requires the generation of the geometric entities of some layer of INPUT group. I.e., if the user wants to simulate only a SWMM model, the proper layer must contain all the information together with the IBER and MESH data. Whereas, an Iber model, without sewer network, requires the definition of, at least, Ground and Boundary conditions layers. Roof layer is optional and when exists it can be linked directly to the Ground or to the Junction layer (if an Iber-SWMM model is simulated). In this sense, an Iber-SWMM model, i.e., a coupled urban drainage simulation, also requires the definition of the Inlet layer and, if there is no flow, the definition of the rainfall data, whether it is by hyetographs or rasters of rain.

It is worth noticing that raster data as topography or infiltration losses can be added to any layer’s group. During the Mesh generation process ( ![]() ) these data, if exists in the project, can be selected. Other raster data, such as rainfall raster, must be defined as a timeseries (

) these data, if exists in the project, can be selected. Other raster data, such as rainfall raster, must be defined as a timeseries (![]() ) by defining the raster name per each time interval. The directory where the raster are located must be provided.

) by defining the raster name per each time interval. The directory where the raster are located must be provided.

Previous to the simulation process (![]() ), a new folder will be created containing the files that calculation engine Iber-SWMM will be used to carry out the simulation, even save the results. As each simulation scenario can be saved independently, different folders will be created. Note if you share the model (*.gpkg and/or *.gps), the folder that contains the results will be lost. So, the model must be re-simulated to generate again the results or consider to share all this information together with the model.

), a new folder will be created containing the files that calculation engine Iber-SWMM will be used to carry out the simulation, even save the results. As each simulation scenario can be saved independently, different folders will be created. Note if you share the model (*.gpkg and/or *.gps), the folder that contains the results will be lost. So, the model must be re-simulated to generate again the results or consider to share all this information together with the model.

2.3.1 Velocity-dependent terms

Velocity-dependent terms of the rheological model must be implemented as a friction slope at each mesh element (Data >> Roughness >> Friction slope…). These parameters can be defined manually or automatically (by a raster file), and are associated to the concept known as ‘Land use’; thus, they can vary spatially.

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Fig. 1. Land uses windows: (a) database of land uses for non-Newtonian flows; (b) list of velocity-dependent parameters according to each rheological model.

2.3.2 Non–Velocity-dependent terms

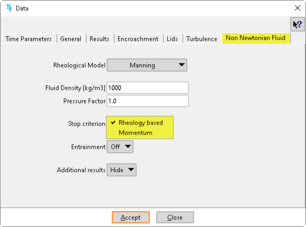

By contrast, non–Velocity-dependent terms can be interpreted as a characteristic of the fluid; thus, they cannot vary spatially –perhaps temporally– and they must be defined as a constant value (Data >> Problem data > Non Newtonian Fluid). This is the case of the flow density, the pressure factor, the Coulomb friction coefficient, the yield stress, etc.

Fig. 2. Problem data window. Non-Newtonian fluid tab allows the selection of the rheological model to be used and other properties.

2.4 Stop criterion

The detention of any fluid is consequence of a balance between resistance and driving forces. Iber-NNF uses an ad hoc numerical scheme that allows the stop of the fluid according to the fluid properties [2], i.e. the rheological model.

Another popular numerical model uses a stopping criterion based on controlling the momentum, where the fluid is made to stop when its momentum is lower than a user-defined fraction of its maximum momentum. However, this criterion lacks a physical basis, as the maximum momentum depends on the avalanche’s characteristics at very different location and time than those when it stops.

Both stop criterion are implemented into Iber-NNF; nevertheless, we encourage to use the ‘Rheology based’ criterion because is physically based.

Fig. 3. Problem data window. Selection of the stop criterion.

3 Governing equations

This section is a brief description of the governing equations of Iber-NNF. Further details about this hydrodynamic module and the numerical scheme used to solve the equations can be found in Sanz-Ramos et al. [2].

3.1 2D shallow water equations for non-Newtonian shallow flows

Iber-NNF solves a particular case of the two-dimensional shallow water equations (2D-SWE), a hyperbolic nonlinear system of three partial differential equations described in Equation (1):

|

|

(1) |

where is the water depth, and are the two components of the specific discharge, is the gravitational acceleration, and are the two bottom slope components computed as , where is the bed elevation, and and are the two friction slope components computed throughout the rheological model. The friction forces exerted over an inclined bed and the pressure terms can be corrected by replacing the gravity acceleration by [9,10,11]. Since the hydrostatic and isotropic pressure distribution cannot be assumed for non-Newtonian flows, as it is done for free surface water flows [12], a factor multiplying the pressure terms in the momentum equations was applied [13]. A value equal to 1 implies hydrostatic and isotropic pressure distribution. The term is entrainment, a process by which solid particles or fragments become incorporated into a moving fluid. The current code partially integrates entrainment formulas based on flow velocity criterion [14], flow height criterion [15] and bed shear stress criterion [16]. The acknowledgment of entrainment is essential for ensuring reliable outcomes and, thus, preventing the underestimation of the volume of snow descending a slope.

3.2 Rheological models

Rheological models to describe both dynamic and static phase of non–Newtonian shallow flows exist for a wide field of applications. In particular, for those related to environmental flows, and more specially for shallow flows, several rheological models have been developed to describe the relationship between the shear stress and the shear rate [17].

From the simplest Potential law to the full –and complex– Bingham model, several rheological models exist in the literature, the development of each one being oriented to achieve a particular reproduction of a fluid behaviour. The aim of Iber-NNF is not to include as rheological models as possible –or exist–; however, there are some models that, although they have been omitted, can be easily integrated into the proposed numerical scheme by slightly adapting the code. This would allow a broader simulation of the behaviour of non–Newtonian shallow fluids.

Two hypotheses are usually considered in non-Newtonian shallow flows modelling: a monophasic fluid, in which the fluid is formed by a unique phase where all components are perfectly mixed, and shear stress grouping, in which the effect of different shear stresses are grouped as five components of a single term [18] as follows:

|

|

(2) |

where represents the dispersive term, the turbulent term, the viscous term, the Mohr–Coulomb terms, and the cohesive term. In these components, the appropriate rheological model for the particular purpose of each work is obtained by selecting one or several components of Equation (2).

Iber-NNF integrates several rheological models to represent the resistance forces that act against flow motion of non–Newtonian flows, such as mudflows, debris flows, snow avalanches, lahars, etc. [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The following sections describe the rheological models implemented expressed in friction slope form ( ).

3.2.1 Manning

The Manning rheological model, an empirical equation widely utilised in hydraulics and hydrology, applies to uniform flow in open channels and is a function of the channel velocity, flow area and channel slope:

|

|

(3) |

where is the Manning coefficient, is the flow velocity and is the flow depth. It is related to turbulent friction ( ), being utilised by several authors for simulating hyperconcentrated flows [19,20,21,22]. The unique value for calibration is the Manning coefficient ( ).

3.2.2 Bingham (simplified)

Since the proposal of the Bingham rheological model [23], several approaches have been introduced to deal with the difficulties on directly obtaining the shear stress proportional to the flow velocity [24]. Assuming an incompressible and homogeneous flow [25,26], the following expression for the viscous ( ) and the Mohr–Coulomb ( ) contributions:

|

|

(4) |

where is the yield stress, is the fluid density, is the flow depth, is the fluid viscosity, is the flow velocity, and is the gravitational acceleration.

3.2.3 Voellmy

Voellmy [27] presented a rheological model that considers the turbulent ( ) and the Mohr–Coulomb ( ) terms as follows:

|

|

(5) |

where is the turbulent friction coefficient, is the Coulomb friction coefficient, is the flow depth and is the flow velocity.

3.2.4 Bartelt

Bartelt et al. [28] developed a new resistance term related to the cohesion, a physical property of the fluid. This rheological model is commonly used together with the Voellmy model, and expresses as follows:

|

|

(6) |

where is the fluid density, is the gravitational acceleration, is the flow depth, is the cohesion, and is the Coulomb friction coefficient.

3.2.5 Dilatant

Similarly to the Manning rheological models, and considering constant sediment concentration and uniform flow, Macedonio and Pareschi [29] derived the following expression: , where is the yield stress, is a proportionality coefficient and is the flow behaviour index.

When = 2 a dilatant flow behaviour is expected:

|

|

(7) |

3.2.6 Viscous

Macedonio and Pareschi [29] also presented the application of the Manning equation to viscous flows by particularizing the parameter = 1. This allows for the representation of viscous flows:

|

|

(8) |

3.2.7 O’Brien

On the other hand, O’Brien and Julien [30] derived an expression for the representation of the shear stress of mudflows, being a quadratic equation that integrates the Mohr–Coulomb term ( ), the viscous term ( ) and the turbulent term ( ) as follows:

|

|

(9) |

where is the yield stress, is the fluid density, is the gravitational acceleration, is the flow depth, is a resistance parameter, is the flow viscosity, is the flow velocity, and is the Manning coefficient.

3.2.8 Herschel-Bulkley

The formulation of Herschel and Bulkley [31] is a generalization of various expressions in which, depending on the value of the coefficient , dilatant, viscous, plastic, etc. behaviours can be derived. This formula follows the following expression:

|

|

(10) |

where is the yield stress, is the fluid density, is the gravitational acceleration, is the flow depth, is a consistency parameter, and is the flow velocity.

3.3 Entrainment

The entrainment is a relevant phenomenon in non-Newtonian flow dynamic modelling because the shear stress between the moving fluid and the terrain generally erode the bottom. This eroded material is then aggregated to the bulk, and might affect it properties (e.g., fluid density) and behaviour.

The effects of entrainment extend beyond altering mass and energy balances. Predicted velocities along the bulk path and the kinetic energy upon reaching the runout zone are also affected. These changes directly influence runout distances and have substantial implications for hazard and risk mapping. Particularly for snow avalanche modelling, entrainment leads to higher predicted flow heights and volumes of avalanches [15,32,33,34,35].

Accurate predictions are crucial for designing infrastructure, such as barriers or dams, as incorrect estimations may result in inadequate protection or increased costs. Therefore, precise consideration of entrainment is essential for determining runout distances and optimizing infrastructure design to mitigate hazards effectively.

3.3.1 Velocity model

This is a simple model that considers mass entrainment as function of the flow velocity. In contrast with another popular model, Iber-NNF considers entrainment when the flow velocity is greater than a threshold ( ).

|

|

(11) |

where is the entrainment rate, which commonly range from 5 to 40·10-5.

3.3.2 Height model

In this model, the entrainment depends on the load of the underlying snow cover as long as its height reaches a fixed minimum value ( ); otherwise, the entrainment will be considered inexistent [15]. This model also integrates an upper limit for the height based on the dry friction law to avoid the dry friction increasing limitless [36]:

|

|

(12) |

where is the entrainment rate, which commonly range from 1 to 8·10-3 s-1, and being the maximum avalanche flux height at which yielding at the basal surface occurs:

|

|

(13) |

3.3.3 Squared velocity model

This equation is similar to the velocity model although the entrainment rate is considered to vary with the squared velocity of the avalanche [15]:

|

|

(14) |

where is the entrainment rate, which commonly range from 4 to 32·10-6.

3.3.4 Bed shear stress model

Similar to how the sediment transport is computed, a new equation to calculate the entrainment as a function of the bed shear stress between the lower snow layer and the avalanche:

|

|

(15) |

where is the entrainment rate, which a range from 1.5 to 12·10-6 m·s-1·Pa-1 is proposed [16].

4 Results

As in the hydrodynamic module for water flows, Iber-NNF also integrates flow depths, velocities, elevation, etc. However, particular results can be activated through Data >> Problem data >> NonNewtonian fluid tab, such as extra topographical information (terrain slope) and impact forces [37,38]. This results essentially applies for dense snow avalanche modelling, but they are not limited to.

Particularly for impact forces, Iber-NNF calculates the dynamic pressure (Equation (16)), the peak dynamic pressure (Equation (17)) and its maximus as follows:

|

|

(16) | |

|

|

(17) |

where is the fluid density and is the fluid velocity.

References

[1] E. Bladé, L. Cea, G. Corestein, E. Escolano, J. Puertas, E. Vázquez-Cendón, J. Dolz, A. Coll, Iber: herramienta de simulación numérica del flujo en ríos, Rev. Int. Métodos Numéricos Para Cálculo y Diseño En Ing. 30 (2014) 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rimni.2012.07.004.

[2] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, P. Oller, G. Furdada, Numerical modelling of dense snow avalanches with a well-balanced scheme based on the 2D shallow water equations, J. Glaciol. (2023) 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.48.

[3] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, El rol de los términos de fricción y cohesión en la modelización bidimensional de fluidos no Newtonianos: avalanchas de nieve densa, Ing. Del Agua. 27 (2023) 295–310. https://doi.org/10.4995/ia.2023.20080.

[4] M. Sanz-Ramos, C.A. Andrade, P. Oller, G. Furdada, E. Bladé, E. Martínez-Gomariz, Reconstructing the Snow Avalanche of Coll de Pal 2018 (SE Pyrenees), GeoHazards. 2 (2021) 196–211. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards2030011.

[5] V. Ruiz-Villanueva, B. Mazzorana, E. Bladé, L. Bürkli, P. Iribarren-Anacona, L. Mao, F. Nakamura, D. Ravazzolo, D. Rickenmann, M. Sanz-Ramos, M. Stoffel, E. Wohl, Characterization of wood-laden flows in rivers, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms. 44 (2019) 1694–1709. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4603.

[6] M. Sanz-Ramos, J.J. Vales-Bravo, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, Reconstructing the spill propagation of the Aznalcóllar mine disaster, Mine Water Environ. 43 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-01000-5.

[7] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, T. Dysarz, Extension of Iber for Simulating Non–Newtonian Shallow Flows: Mine-Tailings Spill Propagation Modelling, Water. 16 (2024) 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16142039.

[8] M. Sanz-Ramos, L. Cea, E. Bladé, D. López-Gómez, E. Sañudo, G. Corestein, G. García-Alén, J. Aragón-Hernández, Iber v3. Reference manual and user’s interface of the new implementations, CIMNE, 2022. https://doi.org/10.23967/iber.2022.01.

[9] Y. Ni, Z. Cao, Q. Liu, Mathematical modeling of shallow-water flows on steep slopes, J. Hydrol. Hydromechanics. 67 (2019) 252–259. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0012.

[10] A. Maranzoni, M. Tomirotti, New formulation of the two-dimensional steep-slope shallow water equations. Part I: Theory and analysis, Adv. Water Resour. 166 (2022) 104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104255.

[11] D. Zugliani, G. Rosatti, TRENT2D❄: An accurate numerical approach to the simulation of two-dimensional dense snow avalanches in global coordinate systems, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 190 (2021) 103343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103343.

[12] V. Te Chow, Open-Channel Hydraulics, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc. New York, USA, 1959.

[13] S.B. Savage, K. Hutter, The motion of a finite mass of granular material down a rough incline, J. Fluid Mech. 199 (1989) 177–215. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089000340.

[14] M. Christen, J. Kowalski, P. Bartelt, RAMMS: Numerical simulation of dense snow avalanches in three-dimensional terrain, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 63 (2010) 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2010.04.005.

[15] M.E. Eglit, K.S. Demidov, Mathematical modeling of snow entrainment in avalanche motion, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 43 (2005) 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2005.03.005.

[16] J. Castelló, Enhancement and application of numerical methods for snow avalanche modelling, Master thesis. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain, 2020.

[17] K. Msheik, Non-Newtonian Fluids: Modeling and Well-Posedness, Universite Grenoble Alpes, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2020. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03099969.

[18] P.Y. Julien, C.A. León, Mudfloods, mudflows and debrisflows, classification in rheology and structural design, in: Int. Work. Debris Flow Disaster 27 November–1 December 1999, 2000: pp. 1–15.

[19] T. Takahashi, Debris flow: mechanics and hazard mitigation, in: ROC-JAPAN Jt. Semin. Mul- Tiple Hazards Mitig., National Taiwan Univerisity, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC, 1985: pp. 1075–1092.

[20] A. Laenen, R.P. Hansen, Simulation of three lahars in the Mount St. Helens area, Washington, using a one-dimensional, unsteady-state streamflow model, 1988. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/wri884004.

[21] M. Syarifuddin, S. Oishi, R.I. Hapsari, D. Legono, Empirical model for remote monitoring of rain-triggered lahar at Mount Merapi, J. Japan Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 (Hydraulic Eng. 74 (2018) I_1483-I_1488. https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.74.I_1483.

[22] A.R. Darnell, J.C. Phillips, J. Barclay, R.A. Herd, A.A. Lovett, P.D. Cole, Developing a simplified geographical information system approach to dilute lahar modelling for rapid hazard assessment, Bull. Volcanol. 75 (2013) 713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-013-0713-6.

[23] E.C. Bingham, An investigation of the laws of plastic flow, Bull. Bur. Stand. 13 (1916) 309–353. https://doi.org/10.6028/bulletin.304.

[24] M. Pastor, B. Haddad, G. Sorbino, S. Cuomo, V. Drempetic, A depth‐integrated, coupled SPH model for flow‐like landslides and related phenomena, Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 33 (2009) 143–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.705.

[25] H. Chen, C.F. Lee, Runout Analysis of Slurry Flows with Bingham Model, J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 128 (2002) 1032–1042. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2002)128:12(1032).

[26] D. Naef, D. Rickenmann, P. Rutschmann, B.W. McArdell, Comparison of flow resistance relations for debris flows using a one-dimensional finite element simulation model, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 6 (2006) 155–165. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-155-2006.

[27] A. Voellmy, Über die Zerstörungskraft von Lawinen, Schweizerische Bauzeitung. 73 (1955) 15. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-61891.

[28] P. Bartelt, C.V. Valero, T. Feistl, M. Christen, Y. Bühler, O. Buser, Modelling cohesion in snow avalanche flow, J. Glaciol. 61 (2015) 837–850. https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126.

[29] G. Macedonio, M.T.T. Pareschi, Numerical simulation of some lahars from Mount St. Helens, J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 54 (1992) 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(92)90115-T.

[30] J.S. O’Brien, P.Y. Julien, Laboratory Analysis of Mudflow Properties, J. Hydraul. Eng. 114 (1988) 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1988)114:8(877).

[31] W.H. Herschel, R. Bulkley, Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi-Benzollösungen, Kolloid-Zeitschrift. 39 (1926) 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01432034.

[32] L. Dreier, Y. Bühler, W. Steinkogler, T. Feistl, M. Christen, P. Bartelt, Modelling Small and Frequent Avalanches, in: Int. Snow Sci. Work. 2014 Proc., 29 Sep - 3 Oct, Banff, Canada, 2014: p. 8. http://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item/2128.

[33] V. Medina, M. Hürlimann, A. Bateman, Application of FLATModel, a 2D finite volume code, to debris flows in the northeastern part of the Iberian Peninsula, Landslides. 5 (2008) 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-007-0102-3.

[34] M. Eglit, A. Yakubenko, J. Zayko, A Review of Russian Snow Avalanche Models—From Analytical Solutions to Novel 3D Models, Geosciences. 10 (2020) 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10020077.

[35] M. Garcia, G. Parker, Entrainment of Bed Sediment into Suspension, J. Hydraul. Eng. 117 (1991) 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1991)117:4(414).

[36] P. Bartelt, B. Salm, U. Gruber, Calculating dense-snow avalanche runout using a Voellmy-fluid model with active/passive longitudinal straining, J. Glaciol. 45 (1999) 242–254. https://doi.org/10.3189/s002214300000174x.

[37] C.J. Keylock, M. Barbolini, Snow avalanche impact pressure - vulnerability relations for use in risk assessment, Can. Geotech. J. 38 (2011) 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-100.

[38] F. Rudolf-Miklau, S. Sauermoser, A.I. Mears, F. Rudolf‐Miklau, S. Sauermoser, A.I. Mears, The Technical Avalanche Protection Handbook, Wiley, Berlin, Germany, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783433603840.

Document

Document information

Published on 27/10/25

DOI: 10.23967/iber.2025.03

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?