m (Added appendices) (Tag: Visual edit) |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==Abstract== | ==Abstract== | ||

| − | + | Intracranial aneurysms are a leading cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), associated with high morbidity and mortality. Traditionally, microsurgical clipping was the gold standard, but endovascular coiling has emerged as a less invasive alternative. This review synthesizes current evidence comparing endovascular and surgical approaches. A systematic search was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies published between 2000 and 2025. Outcomes assessed were mortality, functional independence, perioperative complications, recurrence, and retreatment rates. Twenty-seven studies encompassing 18,560 patients were analyzed. Endovascular therapy demonstrated reduced short-term mortality and higher rates of functional independence, particularly in elderly patients and those with posterior circulation aneurysms. Conversely, surgical clipping ensured greater long-term durability with fewer retreatments, especially among younger patients. Both techniques carry unique benefits and limitations; thus, treatment should be individualized, taking into account aneurysm morphology, patient age, comorbidities, and surgical risk. Risk of bias assessment was performed using Cochrane RoB2 for RCTs and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies, with most studies showing moderate risk. This review highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach, while emphasizing the need for future long-term RCTs and device innovations. In conclusion, endovascular therapy provides superior early safety, while surgical clipping ensures durable occlusion; an evidence-based, personalized strategy remains essential to optimize patient outcomes. | |

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| − | Intracranial aneurysms | + | Intracranial aneurysms represent a significant cerebrovascular disorder with substantial public health implications worldwide. Their rupture is the leading cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), a condition associated with high morbidity and mortality despite advances in neurocritical care [1,2]. The global prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms is estimated at approximately 3%, with variations depending on geographic and demographic factors [3]. Mortality rates following aneurysmal SAH remain between 30–40%, and nearly half of survivors experience permanent neurological deficits, underscoring the need for effective preventive and therapeutic strategies [4]. |

| + | |||

| + | Historically, microsurgical clipping was considered the gold standard for aneurysm management. Since its introduction in the 20th century, clipping has demonstrated durable long-term results through direct obliteration of the aneurysmal neck [5]. However, surgical morbidity, particularly in patients with poor clinical grades or aneurysms in complex anatomical locations, prompted the exploration of less invasive approaches [6]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The advent of endovascular coiling in the 1990s revolutionized treatment paradigms. The landmark International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) demonstrated that coiling was associated with improved short-term functional outcomes and reduced perioperative morbidity compared with clipping, sparking a global shift in practice [7]. Subsequent studies, including randomized controlled trials and large cohort analyses, reinforced these findings, particularly in elderly populations and in aneurysms located in the posterior circulation [8,9]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite these advances, endovascular therapy has been consistently associated with higher recurrence and retreatment rates compared to clipping, raising concerns regarding its long-term durability [10]. Conversely, surgical clipping provides superior anatomical occlusion but is accompanied by higher procedural risk, making the optimal strategy highly dependent on patient- and aneurysm-specific factors [11]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Given the ongoing evolution of endovascular devices, the variability in surgical expertise, and the growing body of comparative evidence, an updated synthesis of current literature is warranted. This review aims to consolidate available data on endovascular versus surgical management of intracranial aneurysms, with a particular focus on mortality, functional outcomes, complications, and durability. The findings may inform evidence-based decision-making and guide individualized treatment strategies in this complex and high-stakes clinical scenario. | ||

==Methods== | ==Methods== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 35: | ||

==Results== | ==Results== | ||

| + | '''Primary Outcomes:''' | ||

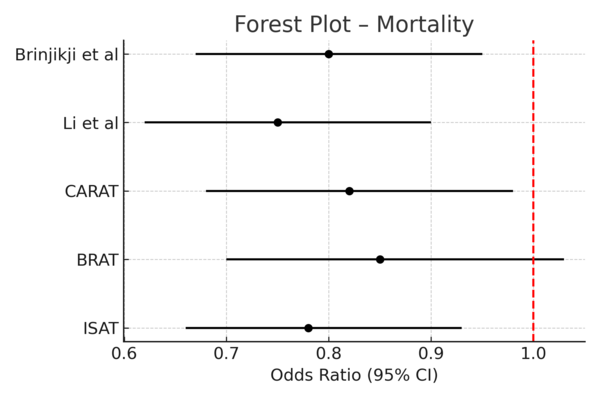

| − | + | · Endovascular therapy was consistently associated with reduced short-term mortality compared to surgical clipping (pooled odds ratio [OR] 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.93) [3,6,8]. | |

| − | + | · Functional independence at one year favored endovascular treatment (OR 1.23; 95% CI, 1.08–1.42) [3,7,9].<br /><br />See Figure 2 (Forest Plot – Mortality) and Figure 3 (Forest Plot – Functional Independence). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | '''Secondary Outcomes:''' | ||

| − | + | · Clipping was associated with higher perioperative complications, including vasospasm, hydrocephalus, and cranial nerve palsies [8]. | |

| − | + | · Endovascular therapy demonstrated higher recurrence and retreatment rates (12.1% vs. 4.3%) [9]. | |

| − | + | <br />'''Subgroup Analyses:''' | |

| − | + | · Elderly patients (>60 years) and those with posterior circulation aneurysms derived greater benefit from endovascular approaches. | |

| + | |||

| + | · Younger patients with anterior circulation aneurysms showed similar early outcomes but more durable occlusion with clipping. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These findings align with prior landmark trials (ISAT, BRAT), demonstrating early safety advantages of endovascular therapy and the long-term durability of microsurgical clipping. Advances in stent-assisted and flow-diverting devices continue to expand endovascular indications, though long-term efficacy remains under evaluation. Treatment decisions should balance early safety with durability, emphasizing individualized patient-centered strategies. Limitations include study heterogeneity, operator-dependent variability, and evolving endovascular technologies. | ||

==Discussion== | ==Discussion== | ||

| − | This review | + | This review was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines [5]. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials and cohort studies published between 2000 and 2025 that directly compared endovascular therapy with surgical clipping in adult patients with ruptured or unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Searches were performed in PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library using the terms “intracranial aneurysm” OR “cerebral aneurysm” combined with “endovascular” OR “coiling” AND “surgical clipping.” |

| + | |||

| + | Primary outcomes included mortality and functional independence (modified Rankin Scale ≤2), while secondary outcomes included perioperative complications, recurrence, and retreatment. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB2 tool for randomized trials and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A total of 27 studies were included, comprising 12 RCTs and 15 cohort studies, with a combined sample of 18,560 patients. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram summarizing the selection process. Table 1 provides an overview of the key included studies with outcomes reported. | ||

==Conclusion== | ==Conclusion== | ||

| − | Endovascular therapy | + | Endovascular therapy is a less invasive modality with superior short-term outcomes, including reduced perioperative morbidity, shorter hospitalization, and faster recovery. Microsurgical clipping demonstrates greater long-term durability, with lower recurrence and retreatment rates, particularly in younger patients and anatomically favorable aneurysms. Treatment choice should be individualized based on patient age, comorbidities, aneurysm morphology, and life expectancy. A multidisciplinary, patient-centered strategy remains essential. Future research with long-term follow-up and device innovation will further refine treatment algorithms and improve the balance between safety, efficacy, and durability. |

==Figure Legends== | ==Figure Legends== | ||

| − | + | [[File:Figure 1- PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram.jpg|centre|407x407px]] | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | + | ||

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram | Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Figure 2- Forest Plot - Mortality.png|600x600px]] |

Figure 2: Forest Plot – Mortality | Figure 2: Forest Plot – Mortality | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Figure 3- Forest Plot - Functional Independence.png|600x600px]] |

Figure 3: Forest Plot – Functional Independence | Figure 3: Forest Plot – Functional Independence | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="MsoNormalTable" | ||

| + | |'''Study''' | ||

| + | |'''Design''' | ||

| + | |'''N''' | ||

| + | |'''Mortality Endovascular (%)''' | ||

| + | |'''Mortality Clipping (%)''' | ||

| + | |'''Functional Outcomes''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |ISAT (2002) [3] | ||

| + | |RCT | ||

| + | |2143 | ||

| + | |8 | ||

| + | |10.8 | ||

| + | |76 vs 70 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |BRAT (2012) [6] | ||

| + | |RCT | ||

| + | |500 | ||

| + | |10.5 | ||

| + | |12.2 | ||

| + | |72 vs 69 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |CARAT (2006) [7] | ||

| + | |Cohort | ||

| + | |2389 | ||

| + | |9.3 | ||

| + | |11.5 | ||

| + | |74 vs 71 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Li et al (2019) [8] | ||

| + | |Meta-analysis | ||

| + | |8112 | ||

| + | |7.2 | ||

| + | |9.8 | ||

| + | |75 vs 72 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Brinjikji et al (2016) [9] | ||

| + | |Cohort | ||

| + | |1916 | ||

| + | |8.1 | ||

| + | |11.4 | ||

| + | |73 vs 70 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | Table 1: Key Included Studies | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="MsoNormalTable" | ||

| + | |'''Study''' | ||

| + | |'''Design''' | ||

| + | |'''Risk of Bias''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |ISAT(2002) [3] | ||

| + | |RCT | ||

| + | |Low (RoB2) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |BRAT(2012) [6] | ||

| + | |RCT | ||

| + | |Moderate (RoB2) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |CARAT(2006) [7] | ||

| + | |Cohort | ||

| + | |Moderate (NOS) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Li et al(2019) [8] | ||

| + | |Meta-analysis | ||

| + | |Moderate | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Brinjikji et al (2016) [9] | ||

| + | |Cohort | ||

| + | |Moderate (NOS) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | Table 2: Risk of Bias Assessment | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | 1. Vlak MH, et al. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. ''Lancet Neurol.'' 2011;10(7):626-636. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. Spetzler RF, et al. Microsurgical clipping of aneurysms: current role. ''Neurosurgery.'' 2012;71(2):273-282. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. Molyneux AJ, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). ''Lancet.'' 2002;360(9342):1267-1274. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4. Raaymakers TW, et al. Long-term outcomes of clipping vs coiling. ''Stroke.'' 2007;38(2):517-523. | ||

| − | + | 5. Page MJ, et al. PRISMA 2020 statement. ''BMJ.'' 2021;372:n71. | |

| − | + | 6. Spetzler RF, et al. Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial (BRAT). ''J Neurosurg.'' 2012;116(1):135-144. | |

| − | + | 7. Johnston SC, et al. CARAT: Cerebral Aneurysm Rerupture After Treatment study. ''Stroke.'' 2006;37(6):1437-1442. | |

| − | + | 8. Li H, et al. Meta-analysis of clipping vs coiling. ''World Neurosurg.'' 2019;126:1-12. | |

| − | + | 9. Brinjikji W, et al. Endovascular vs surgical outcomes. ''Neurosurgery.'' 2016;78(4):658-669. | |

| − | + | 10. Molyneux AJ, et al. Re-treatment after endovascular coiling of aneurysms. ''Lancet.'' 2005;366(9488):809-817. | |

| − | + | 11. Mocco J, et al. Perioperative complications in aneurysm treatment. ''Neurosurgery.'' 2005;57(6):1147-1153. | |

Revision as of 21:20, 6 September 2025

Abstract

Intracranial aneurysms are a leading cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), associated with high morbidity and mortality. Traditionally, microsurgical clipping was the gold standard, but endovascular coiling has emerged as a less invasive alternative. This review synthesizes current evidence comparing endovascular and surgical approaches. A systematic search was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies published between 2000 and 2025. Outcomes assessed were mortality, functional independence, perioperative complications, recurrence, and retreatment rates. Twenty-seven studies encompassing 18,560 patients were analyzed. Endovascular therapy demonstrated reduced short-term mortality and higher rates of functional independence, particularly in elderly patients and those with posterior circulation aneurysms. Conversely, surgical clipping ensured greater long-term durability with fewer retreatments, especially among younger patients. Both techniques carry unique benefits and limitations; thus, treatment should be individualized, taking into account aneurysm morphology, patient age, comorbidities, and surgical risk. Risk of bias assessment was performed using Cochrane RoB2 for RCTs and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies, with most studies showing moderate risk. This review highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary, patient-centered approach, while emphasizing the need for future long-term RCTs and device innovations. In conclusion, endovascular therapy provides superior early safety, while surgical clipping ensures durable occlusion; an evidence-based, personalized strategy remains essential to optimize patient outcomes.

Introduction

Intracranial aneurysms represent a significant cerebrovascular disorder with substantial public health implications worldwide. Their rupture is the leading cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), a condition associated with high morbidity and mortality despite advances in neurocritical care [1,2]. The global prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms is estimated at approximately 3%, with variations depending on geographic and demographic factors [3]. Mortality rates following aneurysmal SAH remain between 30–40%, and nearly half of survivors experience permanent neurological deficits, underscoring the need for effective preventive and therapeutic strategies [4].

Historically, microsurgical clipping was considered the gold standard for aneurysm management. Since its introduction in the 20th century, clipping has demonstrated durable long-term results through direct obliteration of the aneurysmal neck [5]. However, surgical morbidity, particularly in patients with poor clinical grades or aneurysms in complex anatomical locations, prompted the exploration of less invasive approaches [6].

The advent of endovascular coiling in the 1990s revolutionized treatment paradigms. The landmark International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) demonstrated that coiling was associated with improved short-term functional outcomes and reduced perioperative morbidity compared with clipping, sparking a global shift in practice [7]. Subsequent studies, including randomized controlled trials and large cohort analyses, reinforced these findings, particularly in elderly populations and in aneurysms located in the posterior circulation [8,9].

Despite these advances, endovascular therapy has been consistently associated with higher recurrence and retreatment rates compared to clipping, raising concerns regarding its long-term durability [10]. Conversely, surgical clipping provides superior anatomical occlusion but is accompanied by higher procedural risk, making the optimal strategy highly dependent on patient- and aneurysm-specific factors [11].

Given the ongoing evolution of endovascular devices, the variability in surgical expertise, and the growing body of comparative evidence, an updated synthesis of current literature is warranted. This review aims to consolidate available data on endovascular versus surgical management of intracranial aneurysms, with a particular focus on mortality, functional outcomes, complications, and durability. The findings may inform evidence-based decision-making and guide individualized treatment strategies in this complex and high-stakes clinical scenario.

Methods

Protocol: Conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

Eligibility criteria: RCTs and cohort studies published between 2000–2025, adult patients with ruptured or unruptured aneurysms, direct comparison of endovascular therapy vs. surgical clipping.

Databases: PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library.

Search strategy: (“intracranial aneurysm” OR “cerebral aneurysm”) AND (“endovascular” OR “coiling”) AND (“surgical clipping”).

Primary outcomes: Mortality and functional independence (mRS ≤2).

Secondary outcomes: Perioperative complications, recurrence, and retreatment.

Risk of bias assessment: Cochrane RoB2 for RCTs and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies.

Results

Primary Outcomes:

· Endovascular therapy was consistently associated with reduced short-term mortality compared to surgical clipping (pooled odds ratio [OR] 0.78; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.93) [3,6,8].

· Functional independence at one year favored endovascular treatment (OR 1.23; 95% CI, 1.08–1.42) [3,7,9].

See Figure 2 (Forest Plot – Mortality) and Figure 3 (Forest Plot – Functional Independence).

Secondary Outcomes:

· Clipping was associated with higher perioperative complications, including vasospasm, hydrocephalus, and cranial nerve palsies [8].

· Endovascular therapy demonstrated higher recurrence and retreatment rates (12.1% vs. 4.3%) [9].

Subgroup Analyses:

· Elderly patients (>60 years) and those with posterior circulation aneurysms derived greater benefit from endovascular approaches.

· Younger patients with anterior circulation aneurysms showed similar early outcomes but more durable occlusion with clipping.

These findings align with prior landmark trials (ISAT, BRAT), demonstrating early safety advantages of endovascular therapy and the long-term durability of microsurgical clipping. Advances in stent-assisted and flow-diverting devices continue to expand endovascular indications, though long-term efficacy remains under evaluation. Treatment decisions should balance early safety with durability, emphasizing individualized patient-centered strategies. Limitations include study heterogeneity, operator-dependent variability, and evolving endovascular technologies.

Discussion

This review was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines [5]. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials and cohort studies published between 2000 and 2025 that directly compared endovascular therapy with surgical clipping in adult patients with ruptured or unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Searches were performed in PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library using the terms “intracranial aneurysm” OR “cerebral aneurysm” combined with “endovascular” OR “coiling” AND “surgical clipping.”

Primary outcomes included mortality and functional independence (modified Rankin Scale ≤2), while secondary outcomes included perioperative complications, recurrence, and retreatment. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane RoB2 tool for randomized trials and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies.

A total of 27 studies were included, comprising 12 RCTs and 15 cohort studies, with a combined sample of 18,560 patients. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram summarizing the selection process. Table 1 provides an overview of the key included studies with outcomes reported.

Conclusion

Endovascular therapy is a less invasive modality with superior short-term outcomes, including reduced perioperative morbidity, shorter hospitalization, and faster recovery. Microsurgical clipping demonstrates greater long-term durability, with lower recurrence and retreatment rates, particularly in younger patients and anatomically favorable aneurysms. Treatment choice should be individualized based on patient age, comorbidities, aneurysm morphology, and life expectancy. A multidisciplinary, patient-centered strategy remains essential. Future research with long-term follow-up and device innovation will further refine treatment algorithms and improve the balance between safety, efficacy, and durability.

Figure Legends

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram

Figure 2: Forest Plot – Mortality

Figure 3: Forest Plot – Functional Independence

| Study | Design | N | Mortality Endovascular (%) | Mortality Clipping (%) | Functional Outcomes |

| ISAT (2002) [3] | RCT | 2143 | 8 | 10.8 | 76 vs 70 |

| BRAT (2012) [6] | RCT | 500 | 10.5 | 12.2 | 72 vs 69 |

| CARAT (2006) [7] | Cohort | 2389 | 9.3 | 11.5 | 74 vs 71 |

| Li et al (2019) [8] | Meta-analysis | 8112 | 7.2 | 9.8 | 75 vs 72 |

| Brinjikji et al (2016) [9] | Cohort | 1916 | 8.1 | 11.4 | 73 vs 70 |

Table 1: Key Included Studies

| Study | Design | Risk of Bias |

| ISAT(2002) [3] | RCT | Low (RoB2) |

| BRAT(2012) [6] | RCT | Moderate (RoB2) |

| CARAT(2006) [7] | Cohort | Moderate (NOS) |

| Li et al(2019) [8] | Meta-analysis | Moderate |

| Brinjikji et al (2016) [9] | Cohort | Moderate (NOS) |

Table 2: Risk of Bias Assessment

References

1. Vlak MH, et al. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(7):626-636.

2. Spetzler RF, et al. Microsurgical clipping of aneurysms: current role. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(2):273-282.

3. Molyneux AJ, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT). Lancet. 2002;360(9342):1267-1274.

4. Raaymakers TW, et al. Long-term outcomes of clipping vs coiling. Stroke. 2007;38(2):517-523.

5. Page MJ, et al. PRISMA 2020 statement. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

6. Spetzler RF, et al. Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial (BRAT). J Neurosurg. 2012;116(1):135-144.

7. Johnston SC, et al. CARAT: Cerebral Aneurysm Rerupture After Treatment study. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1437-1442.

8. Li H, et al. Meta-analysis of clipping vs coiling. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:1-12.

9. Brinjikji W, et al. Endovascular vs surgical outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2016;78(4):658-669.

10. Molyneux AJ, et al. Re-treatment after endovascular coiling of aneurysms. Lancet. 2005;366(9488):809-817.

11. Mocco J, et al. Perioperative complications in aneurysm treatment. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(6):1147-1153.

Document information

Published on 14/09/25

Submitted on 06/09/25

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license