| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | <big>''' | + | <big>'''Information release right of scientific research institutions in health emergencies: Taking China as the research object'''</big></div> |

| − | <div | + | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> |

| − | + | Shuai Li<sup>a</sup>''<sup>*</sup>''</div> | |

| − | ''<sup>a</sup> | + | ''<sup>a </sup>Law School, Beijing Foreign Studies University, Beijing, 100089, People’s Republic of China'' |

| − | <span id='OLE_LINK28'></span>''<sup>*</sup>Corresponding address: [mailto: | + | <span id='OLE_LINK28'></span>''<sup>*</sup>Corresponding address: [mailto:Norbertlau2019@163.com Norbertlau2019@163.com]'' |

-->==Abstract== | -->==Abstract== | ||

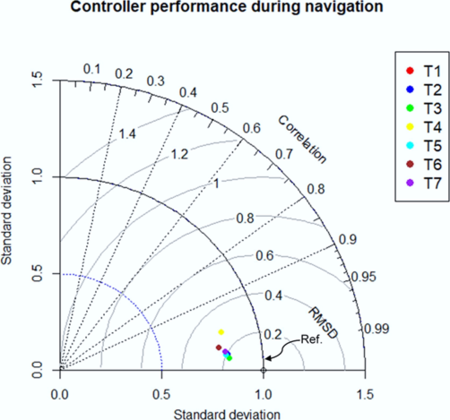

| − | + | The integration of autonomous robotic systems is pivotal for advancing agricultural mechanization. A critical challenge impeding their widespread adoption is the achievement of reliable, self-sufficient navigation, particularly in environments where conventional positioning systems are compromised. While Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), often fused with auxiliary sensors, represent a primary solution for outdoor robot guidance, their susceptibility to signal occlusion necessitates alternative, stable methodologies for consistent operation. Addressing this limitation, this paper presents a novel, model-based navigation algorithm engineered specifically for orchard robots operating under prolonged GNSS denial. The core methodology leverages a deterministic kinematic model, deliberately neglecting higher-order dynamic effects justified by the inherently low operational speeds mandated in precision agricultural settings. This model directly processes commanded trajectory coordinates and real-time vehicle state estimates derived solely from incremental wheel encoders and a steering angle sensor. Within the MATLAB/Simulink environment, this transformation is implemented to generate precise longitudinal velocity and angular steering rate commands necessary for path tracking. Empirical validation was conducted through rigorous simulation and field trials employing a non-holonomic mobile robot platform in representative outdoor conditions. Performance evaluation confirmed the robot’s capability for satisfactory autonomous navigation. Quantitatively, the normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) for lateral path deviation during turning maneuvers ranged between 0.2 and 0.4, while straight-line travel exhibited minimal steering offset, typically within ±0.05 degrees. Furthermore, the correlation coefficient between the model’s predicted steering output and the actual commanded input consistently approached 0.99. Collectively, the results demonstrate that the proposed sensor-minimized, model-driven approach provides a viable and realistic foundation for achieving resilient vehicle navigation in structurally complex agricultural domains where GNSS reliability cannot be assured. | |

| + | |||

| + | '''Keywords''': Autonomous Navigation; Agricultural Robotics; GNSS-Denied Environments; Kinematic Modeling; Path Tracking Control | ||

| − | |||

==1. Introduction== | ==1. Introduction== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The deployment of self-governing robotic platforms within agriculture has accelerated, driven by the need for novel vehicle solutions that elevate farm output, operational efficiency, and the capacity to execute diverse tasks within inherently variable agricultural settings. This trend offers a promising mitigation strategy for the growing scarcity of agricultural labor. Fundamental to the realization of such autonomous mobile systems is the capability for self-directed navigation. While the conceptual foundation for agricultural robotics was established as early as the mid-1980s [1], practical implementation has surged significantly in recent times. This acceleration is largely attributable to concurrent breakthroughs in computational capabilities, sensor technologies [2], and the advent of powerful, affordable processors. Progress in electronics and the commercialization of cost-effective sensors have rendered the development of economically viable robotic platforms for farm environments increasingly feasible. Nevertheless, the aspiration for fully autonomous robotic or vehicular movement remains partially unrealized within contemporary robotics, constrained by persistent technical hurdles. Outdoor navigation for agricultural robots presents particular difficulties, stemming from the challenge of obtaining precise environmental perception amidst fluctuating weather patterns, diverse terrain, and dynamic vegetation. Consequently, developing robust sensing and control strategies capable of accommodating these environmental characteristics is paramount. Supporting this, research by Bac et al. specifically investigated the detrimental impact of environmental variability on the operational efficacy of a harvesting robot [3]. Achieving a precise interpretation of environmental features and deploying resilient technologies for navigation and environmental detection under demanding conditions is crucial for striking an optimal balance between system cost and technological sophistication [4]. | |

| + | |||

| + | Affordability is a critical consideration in agricultural technology development, given the primary end-users are farmers operating within constrained financial frameworks compared to other vehicle markets. System complexity inherently drives cost escalation, making the specific operational environment a vital factor in design philosophy. Orchards, characterized by their semi-structured spatial organization and defined biological architecture, present a highly conducive environment for the initial large-scale adoption of robotics and automation in farming [5]. This suitability is further amplified by a pressing concern: the diminishing availability of skilled seasonal labor poses a substantial risk to orchard sustainability, thereby establishing orchard automation as a critical priority [5]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ongoing research and development efforts signal positive growth indicators for the agricultural robotics sector and the vital transition of these technologies from laboratory prototypes to practical field deployment, irrespective of current manufacturing volumes. Indeed, the pace of innovation in autonomous navigation specifically within agricultural robotics parallels trends observed in the broader automotive market, though the absolute scale of development may currently differ. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Accurate localization constitutes a fundamental pillar for autonomous navigation in mobile robots, demanding sophisticated sensor integration and algorithmic processing. It remains a highly active area demanding continued advancement. Wang et al. explored the utilization of machine vision for robotic positioning and pathfinding [6]. Blok et al. demonstrated a combined Particle Filter and Kalman Filter approach for probabilistic localization, employing a 2D LIDAR scanner to enable in-row navigation for orchard robots [7]. Their empirical findings indicated superior performance of the Particle Filter model over the Kalman Filter in this specific context. The critical influence of the environment on localization efficacy is well-recognized; Schwarting et al. detailed the principal localization challenges encountered by terrestrial robots operating in diverse settings [8]. They offered a comprehensive analysis of existing methodologies tackling these challenges, their inherent limitations, and prospective future directions. Bechar and Vigneault provided a parallel overview of design, development, and operational considerations for agricultural robots, including their constraints, emphasizing the necessity for sensor fusion to achieve adequate localization and environmental awareness, alongside the development of adaptive path planning and navigation algorithms for variable conditions [9]. Contemporary research frequently focuses on enhancing navigation reliability through the fusion of Global Positioning System (GPS) data with complementary sensor modalities. For instance, Winterhalter et al. proposed an approach combining GNSS-referenced maps with GNSS signals for in-field localization and autonomous traversal along crop rows [10]. Thomasson et al. documented progress in automatic guidance and steering control, highlighting commercially available systems primarily reliant on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) [11]. However, these commercial solutions are predominantly tailored for tractors and often necessitate human intervention when encountering unexpected field or navigation anomalies. Alternative configurations include the use of dual RTK-GPS receivers for navigating 4-wheel-steering agricultural rovers, or localization relying on laser scanners combined with wheel and steering encoders, albeit without integrated obstacle avoidance [12,13]. Zaidner and Shapiro presented a model-based state estimation approach for a vineyard robot utilizing sensor fusion. Recognizing the complexity of real-world testing [14], Linz et al. developed a 3D simulation environment using Gazebo for preliminary virtual validation of robotic navigation algorithms employing image-based sensors, laser scanners, and GPS, prior to outdoor deployment [15]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As evidenced by the literature, agricultural machinery and automated guidance systems extensively leverage GNSS for navigation and positioning. However, a significant limitation of GNSS-centric approaches is their inability to dynamically perceive and respond to the immediate environment [16]. Furthermore, sole reliance on GPS proves unreliable within orchards due to signal degradation and multipath interference caused by dense tree canopies during in-row operation [17]. Standard GPS offers limited positional accuracy (typically 1-2 meters), insufficient for precise autonomous navigation. While centimeter-level accuracy solutions (e.g., RTK-GNSS) exist, their high cost presents a barrier. The economic viability of systems is further compromised when integrating other expensive sensors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Beyond localization, achieving full autonomy necessitates integrated environmental mapping and motion planning modules. Understanding the seamless interaction between these sub-systems is essential for the effective verification of overall control software. The inherent complexity of agricultural robotic vehicles, arising from diverse subsystems and demanding operational requirements, suggests that a model-based design (MBD) methodology offers a promising framework for current development efforts. While MBD is well-established and continually evolving within the automotive industry, particularly for embedded systems, its application in agricultural contexts presents distinct modeling and simulation challenges. Therefore, this paper details the development of a navigation control system for an orchard mobile robot utilizing a model-based design paradigm. The core objective is to create a robot capable of autonomous navigation in GNSS-restricted zones, employing minimal sensor interactions, computationally efficient algorithms, and requiring only minor modifications to its base platform configuration. The system leverages a localization strategy predicated on the provision of a pre-existing environmental map. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==2. System description and overview== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The orchard robot used in this research is illustrated in '''Figure 1''', this modular robotic base facilitates the integration of diverse application-specific modules pertinent to horticultural tasks and continues to undergo iterative development [15]. The present research employs this specific platform instance to validate a novel control paradigm designed for autonomous robotic navigation. | ||

| − | + | <div id='img-1'></div> | |

| − | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | |

| − | + | |-style="background:white;" | |

| − | + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image1.png|330px]] | |

| − | + | ||

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | + | |

| − | |- style="background:white;" | + | |

| − | | style="text-align: center;padding:10px;" | [[Image: | + | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;" | '''Figure 1'''. | + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 1'''. Modular carrier robot |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Propulsion is delivered via a hybrid diesel-electric powertrain configuration. A 30 kW diesel engine functions as the primary power source, mechanically coupled to drive a synchronous generator. Traction is provided by four independently powered wheels, each energized by a dedicated 7 kW electric motor. Omnidirectional maneuvering is achieved through an all-wheel steering mechanism, where each wheel’s steering angle is actuated by a separate electric motor. This combined four-wheel drive and four-wheel steering capability necessitates the simultaneous control of eight distinct motion axes. Consequently, the core energy management system employs an industrial multi-axis drive unit. Electrical power, generated by the synchronous alternator reaching up to 380 V AC output at 3000 rpm engine speed, supplies this system. | |

| − | {| class=" | + | |

| − | + | A Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) onboard incorporates rectification circuitry for initial AC to DC power conditioning. This establishes a centralized 600 V DC intermediate power bus. Energy from this high-voltage DC link is subsequently distributed to the multi-axis drive system’s frequency converters. Specifically, eight independent frequency converters are supplied: four dedicated to regulating the traction motors and four managing the steering actuators. | |

| − | | style=" | + | |

| + | Each frequency converter dynamically modulates output voltage and frequency to precisely govern the rotational speed of its assigned motor. Operational safety protocols impose an absolute maximum travel velocity constraint of 8 km/h. Essential sensory inputs for the autonomous navigation controller derive from incremental encoders integrated into the wheel hubs and steering assemblies. The steering encoders deliver precise angular position feedback for each steerable wheel, while the wheel encoders provide real-time measurements of individual wheel rotational velocity during motion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==3. System modelling and simulation== | ||

| + | |||

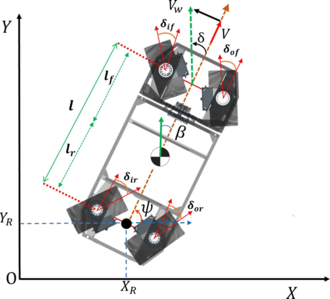

| + | The robotic system depicted in '''Figure 2''' is configured as a four-wheel steering (4WS) vehicle, conceptually akin to a conventional automobile. Its operation is constrained to a two-dimensional (2D) planar domain, wherein idealized rolling motion is presumed in the absence of skidding. The robot’s state is formally defined within a configuration space <math>C</math> described by: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <math>C = (x,y,\psi ,\delta )</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(1) | |

| − | + | |} | |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | + | |

| − | |- style="background:white;" | + | <div id='img-1'></div> |

| − | | style="text-align: center;padding:10px;" | [[Image: | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" |

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image3.png|330px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;" | '''Figure | + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 2'''. Schematic representation of the kinematic configuration employed in the four-wheel steering robotic platform |

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | In this study, a kinematic representation of the 4WS robotic platform has been adopted. Considering the regime of low-velocity traversal, and under the assumption that wheel velocity vectors align with the instantaneous direction of travel while tire forces remain negligible, a non-dynamic kinematic framework has been employed. The resultant formulation is expressed as: | |

| − | + | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | |

| − | {| | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style=" | + | | <math>\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} |

| + | {}&{\dot x = vcos\left( {\psi + \beta } \right)}\\ | ||

| + | {}&{\dot y = vsin\left( {\psi + \beta } \right)}\\ | ||

| + | {}&{\dot \psi = \frac{{vcos\beta }}{{{l_f} + {l_r}}}(tan{\delta _f} - tan{\delta _r})}\\ | ||

| + | {}&{\beta = arctan\left( {\frac{{{l_f}tan{\delta _r} + {l_r}tan{\delta _f}}}{{{l_f} + {l_r}}}} \right)}\\ | ||

| + | {}&{\delta = arctan\left( {\frac{{\omega ({l_f} + {l_r})}}{v}} \right)}\\ | ||

| + | {}&{{\delta _f} = - {\delta _r}} | ||

| + | \end{array}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(2) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Here, <math>\dot x</math> and <math>\dot y</math> designate the Cartesian coordinates of the geometric center located along the rear axle, while ''v'' denotes the linear forward speed. The angular orientation of the vehicle is symbolized by <math>\dot \psi </math>, with <math>\dot \psi = \omega </math> corresponding to the yaw rate. The angular displacements of the front and rear wheels are represented by <math>{\delta _f}</math> and <math>{\delta _r}</math>, respectively, and their combined effect is consolidated in the equivalent steering angle <math>\delta</math>. These steering angles are designed to be equal in magnitude but directed oppositely across the front and rear wheel assemblies. The parameters <math>{l_f}</math> and <math>{l_r}</math> indicate the longitudinal distances from the vehicle’s center of mass to the respective axles. The parameter <math>\beta </math>, denoting the slip angle, is regarded as negligible in the context of low-speed locomotion, with similar assumptions applied to individual wheel side-slip angles. | |

| − | + | The range of admissible values for the steering configuration is constrained within the following interval: <math>\delta \in [ - {45^ \circ }, + {45^ \circ }]</math>, which defines the upper and lower bounds of the equivalent steering angle. This angle serves as a surrogate for representing the aggregate steering effect of both front and rear wheels as if a single wheel were positioned at each end. The equivalent angle is formulated as: | |

| − | {| class=" | + | |

| − | + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | |

| − | + | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | |

| − | {| | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style=" | + | | <math>{\delta _{(r,f)}} = \frac{{{\delta _{iw}} + {\delta _{ow}}}}{2}</math> |

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(3) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | where <math>{\delta _{iw}}</math> and <math>{\delta _{ow}}</math> denote the steering angles of the robot’s inner and outer wheels, respectively. This formulation remains valid under the assumption of symmetrical steering inputs, and the value of <math>\delta</math> is constrained to lie within a specified range, expressed as: |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style=" | + | | |

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>{\delta _{min}} \le \delta \le {\delta _{max}}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | ===3. | + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(4) |

| − | + | |} | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.1 Steering module=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3.1 Steering module | ||

| + | |||

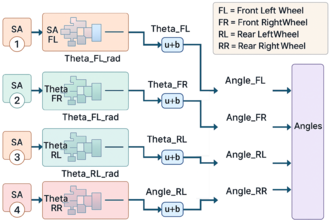

| + | The steering angle of the robotic platform is determined on the basis of the angular displacement of each individual wheel. As illustrated in '''Figure 3''', the model is configured to receive, via the respective wheel module, the incremental rotation angle of each steering motor, measured in radians, which is relayed directly from the motor encoder. | ||

| − | + | <div id='img-1'></div> | |

| − | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" |

| − | |- style="background:white;" | + | |-style="background:white;" |

| − | | style="text-align: center;padding:10px;" | [[Image: | + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image22.png|330px]] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;" | '''Figure | + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 3'''. Structural composition of the steering angle computation module |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | These raw signals are subsequently subjected to a transformation process, whereby the angular increments are converted into their degree equivalents. The steering angle module is mathematically formulated according to the following expression: | |

| − | + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | |

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\theta = \frac{{ - (\emptyset - wheeloffset)*2\pi }}{{Steeringgearratio*Encoderconstant}}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(5) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | 4. The | + | In this formulation, <math>\theta </math> denotes the absolute steering angle in degrees. <math>\emptyset </math> represents the angular increment as recorded by the encoder. The term “offset” compensates for initial misalignments, and the expression incorporates both the mechanical gear reduction ratio and the encoder resolution to ensure accurate angular estimation. |

| + | |||

| + | Steering angle computation is inherently dependent upon the operational steering configuration, which may encompass two-wheel or four-wheel modalities, among others. As illustrated in '''Figure 3''', a modeled computational block was established to determine the steering angle. The input signal for this module originates from the steering encoder output, which undergoes algorithmic transformation to yield angular values, expressed in degrees, as formalized in Equation (5). The associated notational framework utilized in the steering model is itemized in '''Table 1'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Table 1.''' Designated nomenclature for positional states of the steerable wheels | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Symbol''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Designation''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|FL | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|Front left wheel | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|FR | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|Front right wheel | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|RL | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|Rear left wheel | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|RR | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|Rear right wheel | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | As previously outlined, the steering angle determination is dictated by the selected control mode, which may involve either two-wheel steering (2WS) or four-wheel steering (4WS). Under 2WS conditions, the directional modulation is constrained to either the front or rear pair of wheels. In contrast, 4WS systems permit all four wheels to participate in synchronized steering, wherein a coordinated motion pattern is exhibited—two wheels rotate concordantly while the remaining pair adopts an oppositional trajectory. In the present investigation, the system’s behavior has been assessed under the four-wheel steering paradigm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.2 Velocity module=== | ||

| + | |||

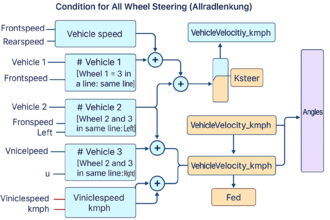

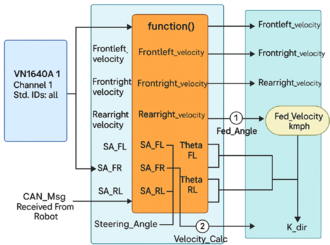

| + | The velocity estimation block ('''Figure 4''') derives robot velocity states from wheel rotational speeds and steering angles. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image26.png|330px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 4'''. Functional architecture of the vehicular velocity estimation module | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the context of robotic locomotion employing an all-wheel steering configuration, the assessment of linear velocity is necessitated for each individual wheel, wherein the influence of both steering angle and directional dynamics is considered paramount. The foundational equations characterizing the linear velocities of the inner and outer wheels, as well as the velocity at the centroid of the robot’s mass distribution, are formally expressed as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\begin{array}{l} | ||

| + | {V_o} = vs \cdot \frac{{2 + bk}}{{2\cos {\theta _o}}}\quad \\ | ||

| + | {V_i} = vs \cdot \frac{{2 - bk}}{{2\cos {\theta _i}}}\\ | ||

| + | V = \frac{{2\pi \eta }}{{irad \cdot 60}}\\ | ||

| + | {V_s} = 2\pi \eta \cdot \frac{{2\cos {\theta _{i,j}}}}{{irad \cdot 60 + 2 \pm bk}} | ||

| + | \end{array}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(6) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Here, <math>{V_o}</math> and <math>{V_i}</math> denote the linear velocities of the outer and inner wheels, respectively; <math>{V}</math> reprsents the forward velocity of the vehicle under rectilinear motion, expressed in metres per second; and <math>{V_s}</math> defines the velocity at the robot’s centre of gravity. The variables <math>{\theta _o}</math> and <math>{\theta _i}</math> correspond to the respective steering angles of the outer and inner wheels. The drive ratio for the actuated wheels is symbolised by '''''irad''''', while '''''b''''' designates the wheelbase length. The curvature parameter '''''k''''', defined as the reciprocal of the turning radius, encapsulates the geometric turning constraint. The composite steering angle <math>{\theta _{i,j}}</math> accounts for steering direction, wheel placement (inner versus outer), and kinematic characteristics specific to wheel position—where '''𝑖''' signifies lateral orientation (left or right) and '''𝑗''' designates the longitudinal axis (front or rear). The angular wheel velocity, '''𝜂''', is expressed in revolutions per minute. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To facilitate velocity estimation, the steering angle and rotational speed of the driving wheels are employed as input parameters. The velocity estimation module is hierarchically structured into three distinct computational sub-blocks, each responsible for deriving the robot’s velocity under specific operational modalities. The upper sub-block is designated for estimating the vehicle’s linear speed under straight driving conditions. The intermediate sub-block is tasked with velocity computation during left-turn maneuvers, whereas the bottom sub-block undertakes analogous calculations for right-turn scenarios. The resulting velocity output—whether under linear or curved trajectory—is subsequently propagated to downstream control layers to inform actuation logic. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.3 Orientation module === | ||

| + | |||

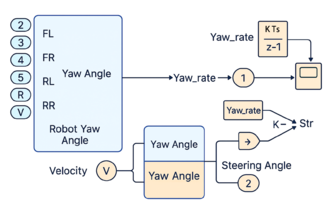

| + | To ensure precise localization of the robot within a defined operational environment, accurate knowledge of its pose—comprising both positional and orientational attributes—is indispensable. Traditionally, the robot’s heading is acquired through external sensory instrumentation. However, in this study, robotic navigation has been designed to function with minimal sensor reliance, particularly in GNSS-denied conditions. Accordingly, a dedicated orientation module was devised to infer the robot’s heading based solely on kinematic parameters, including wheel steering angles and translational velocity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The orientation component is pivotal to the overall localization framework and was developed in accordance with the principles of the kinematic bicycle model. The model is adapted here for integration with a four-wheel steering (4WS) robotic platform. The governing differential equation of the orientation dynamics is expressed as: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\dot \psi = \frac{{VCos\beta }}{{{l_f} + {l_r}}}(tan{\delta _f} - \tan {\delta _r})</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(7) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this formulation, vehicle orientation is derived from the equivalent front and rear steering angles, incorporating necessary offset corrections alongside real-time vehicular velocity. The slip angle '''𝛽''', pertinent under conditions of counter-phase steering in 4WS configurations, is omitted to simplify turning radius computations and enhance directional accuracy. A block-level representation of the orientation module, as implemented in MATLAB for system integration, is depicted in '''Figure 5'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image37.png|330px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 5'''. Computational framework for determining vehicular orientation | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===3.4 CAN transceiver module=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This subsystem facilitates bidirectional data exchange between the robotic platform and the host controller via a Controller Area Network (CAN) bus protocol. It handles signal transmission to the robot while concurrently processing incoming telemetry for machine control applications. The architecture incorporates three core elements: A CAN configuration profile defining bus parameters; A standardized database file (DBC) specifying signal encoding rules; Hardware-specific device initialization settings. | ||

| + | |||

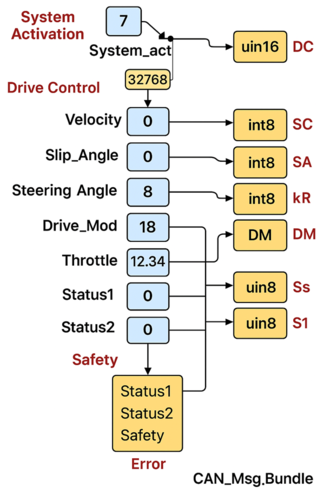

| + | The DBC file critically maps all input/output signal attributes (including scaling, units, and routing), enabling deterministic communication between the robotic agent and supervisory host. '''Figure 6''' illustrates the transmission subsystem implemented in MATLAB® 2018b using Simulink® blocksets, while '''Figure 7''' details the complementary reception architecture developed with the Vehicle Network Toolbox™. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image38.png|330px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 6'''. Data transmission protocol module implemented via the CAN interface | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image39.png|330px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 7'''. CAN-based data reception module integrated within the control system | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The transmission subsystem dispatches command signals at fixed 200 ms intervals to satisfy deterministic timing requirements, whereas the reception block acquires sensor data at a higher 10 ms refresh rate for responsive control. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Raw CAN frames received by the acquisition module undergo signal extraction before being routed to downstream steering and velocity estimation subsystems. This provides the physical parameters (wheel speeds, joint angles, etc.) essential for closed-loop control synthesis. The transmission block additionally integrates: Mode selection registers for dynamically reconfiguring drive profiles (steering mode/throttle mapping); A safety layer generating ISO 11783-compliant diagnostic messages; Continuous bus loading metrics and node health monitoring | ||

| + | |||

| + | The architecture actively verifies network integrity through cyclic redundancy checks while enforcing protocol-specific error confinement strategies during arbitration phases. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==4. Controller design architecture== | ||

| + | |||

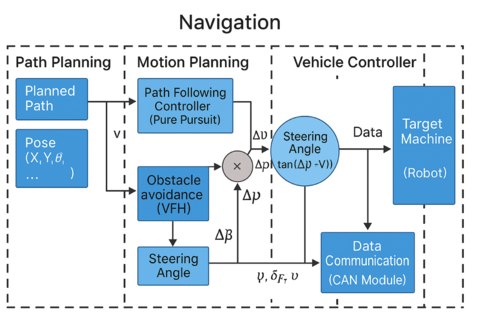

| + | The controller software architecture delineates the high-level structure of constituent modules and their inter-module interactions. As illustrated in '''Figure 8''', the robot’s navigational control system is fundamentally structured around three core computational modules: the path planner, the motion planner, and the vehicle controller. This integrated navigation algorithm is implemented exclusively within the MATLAB® and Simulink® simulation environment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image40.png|480px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 8'''. Hierarchical control architecture devised for autonomous navigational decision-making | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The path planning module processes environmental imagery, translating it into a binary probabilistic map representing navigable space. Specifically, satellite imagery sourced from providers like Google is converted into this occupancy grid format, which subsequently serves as the foundational spatial representation for both robot navigation and self-localization tasks. This generated map explicitly demarcates traversable regions from non-drivable areas (e.g., obstacles, boundaries) within the operational environment. Leveraging this grid map, the module derives an optimal navigable trajectory for the robot. Detailed exposition of the specific path generation algorithms employed is omitted here, as it constitutes a distinct research domain beyond the present article’s scope. Upon successful path computation, this module outputs the requisite sequence of driving coordinates essential for guiding the robot through the designated environment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The motion planning module integrates two critical sub-units: path tracking and obstacle avoidance. Efficient vehicular guidance necessitates robust path tracking control. It is acknowledged that path tracking controller performance and required control laws exhibit significant dependency on the specific robotic platform employed [18]. Nevertheless, the controller implemented herein demonstrates adaptability, requiring minimal recalibration to accommodate variations in physical platform parameters for navigation. Path tracking is accomplished using a Pure Pursuit controller, a geometric method predicated on vehicle kinematics, commonly applied where dynamic effects are secondary considerations [19]. This controller utilizes the current robot pose (position and orientation), the planned waypoint sequence, and a configurable look-ahead distance to compute instantaneous linear and angular velocity commands. The look-ahead distance, defining the point ahead of the vehicle towards which it steers, functions both as a tunable parameter and a dynamically shifting local target during navigation. Concurrently, the obstacle avoidance sub-unit, employing the Vector Field Histogram (VFH) algorithm, calculates steering directives free from collisions with static environmental features such as tree rows, fixed landmarks, bales, or terrain depressions. Consideration of dynamic obstacles necessitates additional sensor layers; consequently, the present model focuses exclusively on static obstacles, which are also inherently accounted for during the initial mapping and path planning phases. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The vehicle controller actuates the commands generated by the motion planner module. It translates the computed linear and angular velocity setpoints into specific translational velocity and steering angle commands appropriate for the target robotic platform. These actionable directives are transmitted to the physical robot via a dedicated data communication interface. Crucially, sensor feedback – including wheel encoder data and steering angle measurements – is relayed back to the path tracking controller, enabling continuous closed-loop correction to maintain the desired trajectory under kinematic constraints. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===4.1 Lateral control design strategy=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | To ensure strict adherence to the pre-defined navigation path, the implementation of an effective lateral control strategy is indispensable for governing vehicular steering dynamics. In the present study, robotic trajectory tracking has been facilitated through a pure pursuit control scheme, integrated with vehicle odometry data and a two-dimensional reference map. The realization of accurate navigation necessitates the simultaneous orchestration of both lateral and longitudinal control actions. Specifically, the steering control law—mathematically represented in Eq. (8)—is composed of a heading error correction (yaw/orientation compensation) and lateral position deviation suppression relative to the designated path: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>{\delta _{str}} = Heading\;{\rm{error}} + Latera{l_\;}_{}{\rm{error}}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(8) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The heading error <math>{\psi _e}</math> is defined as the angular deviation between the target path orientation <math>{\psi _{desired}}</math> and the robot’s actual heading <math>{\psi _{vehicle}}</math>, whereas the lateral error quantifies the perpendicular displacement between the vehicle’s center of gravity and the reference trajectory: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} | ||

| + | {{\psi _e} = {\psi _{desired}} - {\psi _{vehicle}}}\\ | ||

| + | {{e_{ra}} = {V_x}sin\psi + {V_y}cos\psi } | ||

| + | \end{array}} \right.</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(9) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Here, <math>{V_x}</math> and <math>{V_y}</math> respectively represent the vehicle’s longitudinal and lateral velocity components. As detailed in Section 3, under the employed four-wheel steering (4WS) configuration—illustrated in '''Figure 9'''—the lateral velocity component is considered negligible at low speeds to facilitate optimal steering precision. Consequently, Eq. (9) may be reexpressed as: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>{\delta _{str}} = {V_x}sin\psi + {\psi _{desired}} - {\psi _{vehicle}}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(10) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image49.png|360px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 9'''. Depiction of the elWobot’s inverse four-wheel steering configuration under zero lateral slip conditions | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | This specific control regime, wherein the lateral slip is eliminated, is termed the Zero-side-slip maneuver, a condition characteristically achieved under reduced velocity conditions. Under such circumstances, the heading angle <math>\gamma </math> is equated with the vehicle’s course direction <math>\psi</math>, i.e., the actual trajectory orientation: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="vertical-align: top;margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\gamma = \psi + \beta </math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(11) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | However, due to physical constraints imposed by steering geometry and the attainable side-slip angle <math>\beta </math> , the permissible steering angle <math>{\delta _{str}}</math> required for trajectory realization is bounded as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="vertical-align: top;margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\psi - {\beta _{\max }} \le {\delta _{str}} \le \psi + {\beta _{max}}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(12) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Alternatively, Eq. (12) provides the steering angle condition necessary to achieve the desired orientation alignment for trajectory following. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\psi - {\beta _{max}} \le {\delta _{str}} \le \psi + {\beta _{max}}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(13) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The configuration illustrated in '''Figure 9''' represents the elWobot in a 4WS-negative alignment during the Zero-side-slip maneuver. | ||

| + | |||

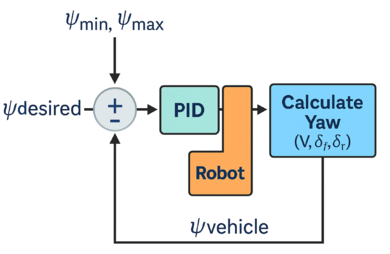

| + | To guarantee robust navigation, the selection of the appropriate steering actuation is critical. In this context, the desired heading rate <math>{\psi _{desired}}</math> is generated by the motion planning module and subsequently converted into vehicle steering commands. To enhance controller efficacy, a hybrid control architecture—integrating a pure pursuit controller with a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) mechanism—has been adopted, as shown in '''Figure 10'''. The choice of this structure is motivated by the pure pursuit controller’s strong performance across a broad speed range, while the PID block ensures stabilizing feedback control, effectively addressing transient deviations from the desired path. Although PID tuning is nontrivial, such controllers remain the most extensively utilized and trusted feedback mechanisms in industrial systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Due to limitations in sensor-based localization, the robot’s actual heading '''𝜓''' is inferred indirectly via its steering angle and velocity. The heading error is regulated by the PID controller, which is structured as a nonlinear, discrete-time single-input single-output (SISO) system constrained by predefined saturation bounds: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>\begin{array}{l} | ||

| + | {\psi _{desired}}\\ | ||

| + | {\psi _{min}}/{\psi _{max}}\\ | ||

| + | PID\\ | ||

| + | Robot\\ | ||

| + | Calculat{e_{}}Yaw({V_x},{\delta _{str}},{e_{tra}})\\ | ||

| + | {\psi _{vehicle}} | ||

| + | \end{array}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(14) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The control architecture for heading correction is delineated in '''Figure 10'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image58.png|390px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 10'''. PID control topology formulated for directional correction | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===4.2 Vehicle longitudinal control=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | To regulate the robot’s longitudinal dynamics, a velocity control strategy has been adopted to ensure both sustained cruising at a predefined speed and reliable braking performance. The principal objective of this control module is the minimization of the velocity tracking error, defined as the discrepancy between the reference velocity ( <math>{V_{set}}</math>) and the actual velocity of the robot ( <math>{V_{a}}</math>). Additionally, the system is designed to exhibit rapid dynamic response characteristics with minimal velocity overshoot. In pursuit of these objectives, a proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controller has been implemented. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>{v_c} = P{V_e} + I\int_0^t {{V_e}} dt + D{V_e}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(15) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {| style="margin:auto;width: 100%;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <math>{V_e} = {V_{set}} - {V_a}</math> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | | style="width: 5px;text-align: right;white-space: nowrap;"|(16) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Here, <math>{v_c}</math> denotes the controller’s output command for velocity adjustment, while <math>{V_e}</math> represents the instantaneous velocity error. The parameters 𝑃, 𝐼, and 𝐷 correspond to the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively. To prevent excessive acceleration and ensure system safety, the maximum permissible controller output velocity <math>{\nu _{c,max}}</math> has been constrained to 2.25 m/s. This ceiling serves both as a protective measure against over-speed conditions and as an anti-windup mechanism integrated within the PID control structure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The selection of the 2.25 m/s upper bound for <math>{v_c}</math> is motivated by the mechanical limitations of the robotic platform, whose rated top speed is approximately 8 km/h (equivalent to 2.22 m/s). A marginal tolerance of +0.03 m/s was introduced to accommodate transient fluctuations, which typically oscillated between 8.0 and 8.1 km/h during empirical evaluation. By imposing this constraint, potential escalation of controller output beyond the safe operational envelope is effectively mitigated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===4.3 Model-based PID controller tuning=== | ||

| + | |||

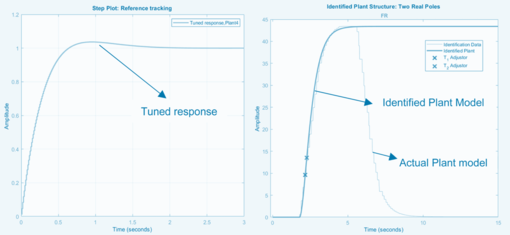

| + | Effective controller implementation necessitates precise calibration of gain parameters to achieve optimal system performance. Post-design PID tuning constitutes a critical phase for determining ideal proportional, integral, and derivative coefficients that govern controller behavior. While conventional manual tuning remains prevalent, this approach demands considerable expertise from control engineers and frequently evolves into a protracted, iterative process. To circumvent these limitations, our research adopts an automated model-based tuning framework leveraging MATLAB/Simulink’s computational ecosystem. Specifically, we employ Simulink Control Design™ alongside the System Identification Toolbox™ to implement this data-driven methodology. The technique requires a linearized plant approximation, presenting implementation challenges for our inherently nonlinear robotic system. To address this, operational open-loop response datasets are acquired under controlled input conditions. These experimental datasets enable localized linearization within defined operational envelopes, permitting the PID tuner to construct region-specific transfer function approximations. Our implementation utilizes reference trajectory tracking with bounded output constraints during optimization, applying this standardized approach to both steering and velocity control subsystems. '''Figure 11''' illustrates this model-based workflow for steering control, where a dedicated plant model is empirically derived from robotic steering response characteristics. Subsequent system identification procedures generate the foundational transfer function model essential for PID coefficient optimization. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image66.png|510px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 11'''. Steering controller calibration via model-informed PID parameter tuning | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The velocity control subsystem undergoes specialized tuning within the navigational velocity spectrum (0.45–2.25 m/s), reflecting operational boundary conditions. Strategic tuning prioritizes lower velocity regimes to prevent destabilization during slow-speed maneuvers while maintaining acceptable higher-speed responsiveness. As documented in '''Table 2''', the finalized gain parameters reflect platform-specific optimization for both control dimensions. Analysis of tuned responses reveals an intentional design compromise: Minor overshoot (observable in steering response plots) is deliberately preserved to enhance transient performance characteristics. Complete overshoot elimination induces excessive system lethargy, extending stabilization periods beyond functional requirements. Consequently, controller calibration embodies a deliberate equilibrium between dynamic responsiveness and stabilization precision—a fundamental tradeoff in transient performance optimization. This balance ensures adequate reference tracking agility without compromising operational stability, particularly crucial during trajectory execution under variable inertial conditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Table 2.''' Optimized gain parameters for PID-based regulation of velocity and steering dynamics | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Control''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''P''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''I''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''D''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Velocity''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|0.5106 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|2.153 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|-0.005 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Steering''' | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|1.35 | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|3.537 | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|0.30 | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

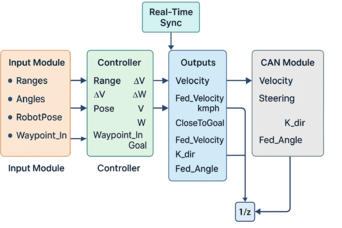

| + | ===4.3 Model integration=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The comprehensive navigation framework synthesizes unit-level and subsystem components into an integrated operational model. This architectural integration establishes deterministic data exchange protocols across functional segments, enabling holistic system validation. A significant advantage of this modular design lies in its cross-project reusability: Pre-validated components accelerate development cycles for future autonomous platforms. Debugging efficiency is substantially enhanced through fault isolation capabilities, allowing targeted module inspection rather than full-system analysis. As visualized in '''Figure 12''', the implemented robotic navigation system partitions functionality into four principal domains: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image67.png|342px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 12'''. Fully integrated and operational model of the robotic navigation framework | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | (1) Sensor Fusion Interface: Processes both live sensor streams and simulated inputs essential for localization. This includes ingestion of trajectory waypoint sequences generated by path planning algorithms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (2) Motion Control Core: Embeds the Pure Pursuit tracking controller that computes steering directives using egocentric localization estimates and navigational waypoints. Pose data originates from odometric measurements correlated against prior path planning operations on occupancy grid maps. These environmental representations derive from georeferenced 2D raster workspace models. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (3) Kinematic Output Hub: Transmits derived velocity setpoints and steering directives to drive systems. Continuously monitors Euclidean distance to target coordinates, issuing null motion commands when the robot enters predefined terminal proximity thresholds. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (4) CAN Communication Gateway: Translates kinematic directives into Controller Area Network messages for actuator control. Incorporates diagnostic telemetry channels and failsafe triggers for real-time system health monitoring. | ||

| + | |||

| + | All computational processes execute within a rigorously enforced 10ms deterministic cycle. Since native Simulink® lacks inherent real-time capability, temporal synchronization is achieved through dedicated Real-Time Sync blocks. These enforce hardware-timed execution intervals that emulate embedded deployment conditions during simulation. The fail-safe subsystem autonomously triggers protective shutdown protocols upon detecting critical anomalies, including actuator faults or deviation beyond safe operating envelopes. Diagnostic messaging provides continuous state observability through standardized SAE J1939 telemetry frames. This temporal formalization ensures controller outputs maintain phase alignment with sensor inputs - a critical requirement for closed-loop stability during high-speed navigation. The synchronized execution environment further enables valid performance benchmarking against real-world timing constraints prior to physical deployment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==5. Simulation results and discussion== | ||

| + | |||

| + | This segment presents empirical validation results for the elWObot robotic platform’s navigation controller through co-simulation and field trials. The integrated development framework leveraged MATLAB/Simulink for model-based design, incorporating both virtual simulation and hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) verification. Successful algorithm deployment occurred in unstructured outdoor environments, specifically cobblestone pathways and densely vegetated terrain engineered to simulate agricultural field irregularities and off-road conditions. Under these challenging substrates, the system exhibited consistently reliable operational performance and trajectory adherence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===5.1 Robot velocity response=== | ||

| + | |||

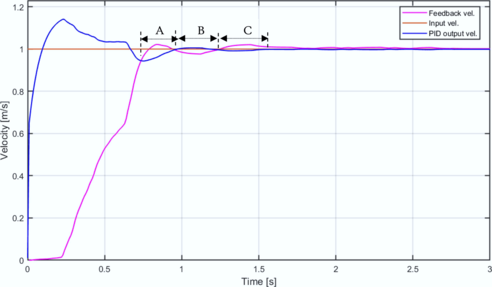

| + | Performance characterization was conducted at a target operational velocity of 1 m/s within the Wenzhou Vocational College of Science and Technology. While orchard validation remains pending platform refinements, the AST terrain provided sufficient stochastic disturbances for preliminary evaluation. '''Figure 13''' demonstrates the optimized velocity tracking behavior, with model execution at 10ms intervals contrasting with 200ms CAN bus update cycles. The PID controller exhibits characteristic transient dynamics: an intentional overshoot to 1.1 m/s occurs within the initial 200ms, subsequently decaying exponentially to converge within ±1% of the setpoint at t=1s. This overshoot magnitude constitutes a deliberate design parameter to overcome stiction-induced torque requirements at the wheel-terrain interface. Actual velocity feedback (measured via wheel encoders) demonstrates second-order following behavior, achieving asymptotic stability at t=1.8s with near-zero steady-state error. Segments A-C confirm consistent tracking fidelity during sustained operation without observable oscillation. Though enhanced disturbance rejection could theoretically be achieved through gain elevation, such tuning induces hypersensitivity to inertial perturbations and reduces stability margins. Consequently, the implemented PID configuration represents an optimal compromise between transient acceleration capability and robust velocity regulation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image68.png|492px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 13'''. Temporal response of the robot’s velocity following PID gain optimization | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===5.2 Robot steering response=== | ||

| + | |||

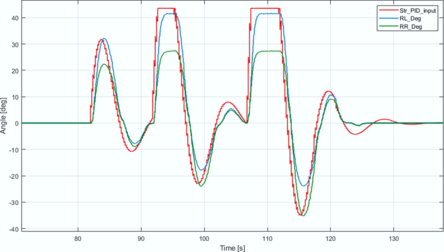

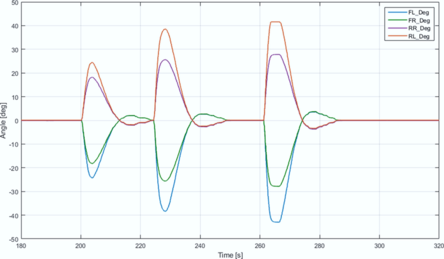

| + | To evaluate directional control fidelity, the elWObot executed pre-mapped trajectories at its optimized operational velocity of 1 m/s (established in Section 5.5 following comparative velocity trials). All turning maneuvers were digitally recorded and synchronously compared against commanded steering inputs and actuator responses. During critical testing sequences observed from the vehicle’s frontal perspective, the robotic system initiated right-turn maneuvers. Leveraging its four-wheel-independent-steering (4WS) architecture, the platform implemented negative-phase coordination where front and rear axles counter-steered to minimize turning radius. As evidenced in '''Figure 14''', the steering controller effectively translated reference inputs (Str_PID_input) into wheel-angle outputs while maintaining Ackermann-compliant kinematics. This necessitates greater deflection of inner wheels relative to outer wheels during curvature negotiation - a behavior confirmed by rear-left wheel (RL_deg) consistently exceeding rear-right wheel (RR_deg) angular displacement. | ||

| + | |||

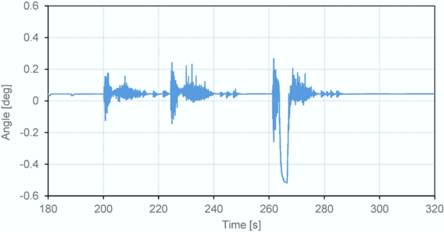

| + | Initial turn execution demonstrated exceptional tracking performance across all wheels. Subsequent maneuvers, however, revealed a systematic discrepancy at extreme steering demands: the inner wheel plateaued at 42°±0.5° tolerance versus the 45° command input ('''Figure 14'''). This limitation stems from inherent kinematic boundaries hard-coded during developmental modeling, where ±42° constitutes the mechanical steering stop. Consequently, the control algorithm intentionally clamps inputs at 45° to emulate physical stops with operational margin. Additional signal phase offsets observed between commanded and achieved angles derive from deterministic CAN bus communication latency operating at 200ms cycles. Comprehensive wheel-angle trajectories during transitional states appear in '''Figure 15''', further validating the 42° saturation threshold. Crucially, sideslip angle (β) variations remained below 1.2° throughout testing ('''Figure 16'''), exhibiting negligible influence on vehicle orientation or steering dynamics per Eqs. 2 and 15. This insensitivity confirms the theoretical advantage of negative-phase 4WS over conventional 2WS systems in slip mitigation. Persistent β offsets of 0.3°±0.1° originated from minor wheel-alignment inconsistencies at neutral positions, though these remained within operational tolerances for agricultural contexts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image69.png|444px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 14'''. Steering angle dynamics in response to PID-regulated input signals | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image70.png|444px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 15'''. Multi-wheel steering angle response elicited by the applied control input | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image71.png|444px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 16'''. Quantitative evaluation of the robot’s sideslip angle (β) during maneuvering | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===5.3 Robot yaw response=== | ||

| + | |||

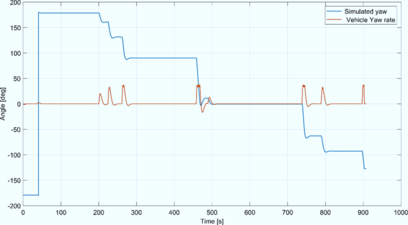

| + | '''Figure 17''' demonstrates close correlation between simulated yaw predictions and experimentally measured yaw rates during trajectory execution. Initial conditions established the robot’s heading at ψ₀ = 180° (π radians) relative to magnetic north. Throughout linear navigation from t=0–200s, both datasets maintained directional stability with angular deviations below ±0.5°. A deliberate 10° yaw rate perturbation introduced at t=200s was accurately replicated in the simulation model within 0.3° RMS error. This tracking fidelity persisted during subsequent maneuvers, with synchronized responses observed at t=480s when commanded directional changes occurred. Here, the simulation registered a 90° orientation shift while physical constraints limited the actual yaw rate to 45° – a discrepancy attributable to steering linkage saturation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image72.png|408px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 17'''. Comparative analysis of simulated versus empirical yaw rate responses | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fundamental to this analysis is the established sign convention: positive values denote counterclockwise rotation (viewed top-down), while negative values indicate clockwise motion. The simulation’s negative yaw manifestation at t=760s correctly represented the vehicle’s reversed directional state upon path completion. Notably, the platform returned to its initial geospatial coordinates but with inverted orientation (heading = -180°), confirming successful loop closure despite directional reversal. This terminal state aligns with conventional vehicle dynamics frameworks where magnetic north corresponds to 0° yaw. The persistent 180° offset throughout testing originated from intentional initialization parameters rather than measurement drift, as confirmed by post-mission inertial validation. Kinematic discrepancies at extreme steering demands (e.g., t=480s) highlight the model’s capacity to capture saturation effects inherent to physical systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===5.4 Robot navigation testing=== | ||

| + | |||

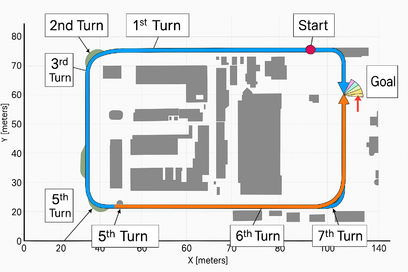

| + | Conventional navigation strategies for car-like robotic platforms typically operate within reduced-configuration planar spaces defined solely by Cartesian x-y coordinates. '''Figure 18''' demonstrates trajectory execution within such an environment, simulating agricultural row-traversal behaviors including linear inter-row navigation and headland turning maneuvers. Path planning was implemented via Probabilistic Road Map (PRM) methodology on occupancy grid maps, where white regions denote navigable terrain and black zones represent obstructions. Notably, this approach disregards non-holonomic constraints inherent in wheeled platforms. The triangular representation in '''Figure 18''' illustrates the robot’s orientation during traversal at Wenzhou Vocational College of Science and Technology’ test facility. Velocity trials (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 m/s) revealed optimal tracking fidelity at 1.0 m/s ('''Figure 18'''f), with comprehensive velocity-dependent analysis detailed in Section 5.5. Trajectory adherence was quantified through superimposed path visualization (blue trajectory), though Turn 4 exhibited corner-cutting behavior—manifesting as increased turning radius relative to waypoint positioning. This phenomenon stems from discretized path planning and non-holonomic limitations preventing instantaneous directional changes, necessitating minimum rotational radii. Such constraints are particularly pronounced in Ackermann-steered platforms (2WS/4WS) compared to differential/skid-steer systems capable of zero-radius turns. Mitigation strategies include implementing continuous-curvature path planners and optimizing pure pursuit controllers through velocity-adaptive lookahead distances. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[File:20250620 174112.png|408x408px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 18'''. Real-world trajectory tracking of the robot along a predefined path at the AST test facility, Wenzhou Vocational College of Science and Technology | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

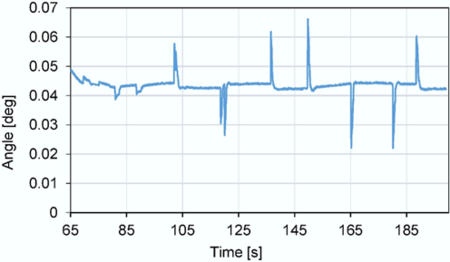

| + | Beyond qualitative assessment, rigorous quantitative evaluation examined linear tracking (Start → Turn 1) and turning performance across four maneuvers. '''Figure 19''' documents straight-line traversal errors bounded within ±0.05° tolerance, with transient overshoots attributable to surface-induced disturbances challenging controller robustness. Turning characteristics ('''Figure 18''') were statistically analyzed in '''Table 3''', revealing a maximum instantaneous peak error of 27% at Turn 1. Crucially, this metric represents localized deviation rather than holistic steering fidelity—a consequence of modeling simplifications where steering angle was computed as the absolute average of front-wheel displacements. Physical systems exhibit asymmetric wheel angles due to Ackermann kinematics, constraining achievable yaw rates. This approximation propagates to yaw estimation (Eq. 2), where velocity-dependent transients precede steady-state convergence. True maneuvering precision is better quantified by average angular offsets below 5° across all turns ('''Table 3'''). Negative steering values indicate leftward deflection, with kinematic saturation evidenced by the front-right wheel’s inability to achieve the 42.97° command angle—validating modeled mechanical limits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id='img-1'></div> | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="margin: 0em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;width:auto;" | ||

| + | |-style="background:white;" | ||

| + | |style="text-align: center;padding:10px;"| [[Image:Draft_Wu_280690876-image74.png|450px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="background:#efefef;text-align:left;padding:10px;font-size: 85%;"| '''Figure 19'''. Navigation performance of the robot during linear path traversal | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Table 3. '''Comparative metrics of steering input angles and corresponding yaw responses across multiple turning scenarios | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Turn''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Peak Input angle (deg.)''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Peak yaw angle (deg.)''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Peak error (%)''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Avg.offset (deg.)''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''FL angle''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''FR angle''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''RL angle''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''RR angle''' | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|'''Equivalent Steering angle''' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|1st | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|28.28 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|20.50 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|27.5 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|1.19 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|-24.10 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|-18.11 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|24.18 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|18.15 | ||

| + | | style="border-top: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|22.12 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|2nd | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|38.42 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|33.04 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|14.0 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|3.06 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-38.27 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-25.57 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|38.45 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|25.60 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|32.18 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|3rd | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|42.97 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|36.44 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|15.2 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|4.26 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-41.95 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-27.83 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|41.59 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|27.82 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|34.70 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|4th | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|42.97 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|36.44 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|15.2 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|5.04 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-41.95 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-27.83 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|41.59 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|27.82 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|34.71 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|5th | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|15.95 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|12.69 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|20.4 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|1.15 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-13.95 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-12.26 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|14.13 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|12.22 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|13.63 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|6th | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|42.97 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|36.44 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|15.2 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|5.04 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-41.95 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|-27.83 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|41.59 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|27.82 | ||

| + | | style="vertical-align: top;"|34.47 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|7th | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|38.23 | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|32.28 | ||

| + | | style="border-bottom: 1pt solid black;vertical-align: top;"|15.5 | ||