| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==Abstract== | ==Abstract== | ||

| − | Iber is a two-dimensional hydraulic model for the simulation of free surface flow in rivers and estuaries, and the simulation of environmental processes in fluvial hydraulics. Since the release of the first version of Iber, which included a hydrodynamic calculation engine fully coupled with sediment transport processes and turbulence, it has evolved to become a free surface flow modelling tool for highly complex environmental processes. This document presents the developments made for version 3, specifically, for the new calculation module for the simulation of shallow non-Newtonian flows called | + | Iber is a two-dimensional hydraulic model for the simulation of free surface flow in rivers and estuaries, and the simulation of environmental processes in fluvial hydraulics. Since the release of the first version of Iber, which included a hydrodynamic calculation engine fully coupled with sediment transport processes and turbulence, it has evolved to become a free surface flow modelling tool for highly complex environmental processes. This document presents the developments made for version 3, specifically, for the new calculation module for the simulation of shallow non-Newtonian flows called Iber-NNF. The shallow water equations are solved using an ad-hoc numerical scheme focused on the simulation of this type of flow in nature (e.g., steep slopes, irregular geometries). The graphical user interface (GUI) has been adapted to the module's new features to achieve a simple and user-friendly workflow. |

'''Keywords''': non-Newtonian flows, snow avalanches, mud/debris flows, hypercongested flows, Iber | '''Keywords''': non-Newtonian flows, snow avalanches, mud/debris flows, hypercongested flows, Iber | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

==Resumen== | ==Resumen== | ||

| − | Iber es un modelo numérico bidimensional de simulación de flujo turbulento en lámina libre en régimen no-permanente, y de procesos medioambientales en hidráulica fluvial. Desde el lanzamiento de la primera versión, que incluía un motor de cálculo hidrodinámico para completamente acoplado con procesos de transporte de sedimento y turbulencia, Iber ha ido evolucionando hasta convertirse en una herramienta de modelización de flujo de agua en lámina libre de procesos ambientales de elevada complejidad. En este documento se presentan los desarrollos realizados para la versión 3, concretamente para el nuevo módulo de cálculo para la simulación de flujos no-newtonianos someros denominado | + | Iber es un modelo numérico bidimensional de simulación de flujo turbulento en lámina libre en régimen no-permanente, y de procesos medioambientales en hidráulica fluvial. Desde el lanzamiento de la primera versión, que incluía un motor de cálculo hidrodinámico para completamente acoplado con procesos de transporte de sedimento y turbulencia, Iber ha ido evolucionando hasta convertirse en una herramienta de modelización de flujo de agua en lámina libre de procesos ambientales de elevada complejidad. En este documento se presentan los desarrollos realizados para la versión 3, concretamente para el nuevo módulo de cálculo para la simulación de flujos no-newtonianos someros denominado Iber-NNF. La resolución de las ecuaciones de aguas someras se lleva a cabo mediante un esquema numérico propio enfocado a la simulación de este tipo de flujos en la naturaleza (p.ej., pendientes elevadas, geometrías irregulares). La interfaz gráfica de usuario (GUI) se ha adaptado para con las nuevas características del módulo con el fin de obtener un flujo de trabajo sencillo y amigable. |

'''Palabras clave''': flujos no-newtonianos, aludes, flujo de lodos/escombros, flujos hipercongestionados, Iber | '''Palabras clave''': flujos no-newtonianos, aludes, flujo de lodos/escombros, flujos hipercongestionados, Iber | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

Numerical modelling of natural phenomena, particularly weather-related which are the 90 % of global disasters, is essential to analyse and predict hazardous situations for the people, the economy and the environment. The evolution of these numerical tools, from simple one-dimensional to complex three-dimensional models, to simulate hydrological hazards like floods, mass movements, and avalanches is challenging, especially those in which the fluid can be characterized as non–Newtonian flows. | Numerical modelling of natural phenomena, particularly weather-related which are the 90 % of global disasters, is essential to analyse and predict hazardous situations for the people, the economy and the environment. The evolution of these numerical tools, from simple one-dimensional to complex three-dimensional models, to simulate hydrological hazards like floods, mass movements, and avalanches is challenging, especially those in which the fluid can be characterized as non–Newtonian flows. | ||

| − | + | Iber-NNF was developed, based on Iber [<span id='cite-_Bib001'></span>[[#_Bib001|1]]], as a depth-averaged two-dimensional hydrodynamic numerical tool to simulate non–Newtonian shallow flows. To that end, a particular numerical scheme based on an upwind discretisation to ensure a proper balance between the non–velocity-dependent terms of the shear stresses and the pressure forces has been developed [<span id='cite-_Bib007'></span>[[#_Bib002|2]]]. This ensures the stop of the fluid according to the rheological properties of the fluid, even in steep slopes and complex geometries. The code besides being validated and applied in theoretical, analytical, and real situations of common and non–common non–Newtonian shallow flows [<span id='cite-_Bib002'></span>[[#_Bib002|2]],<span id='cite-_Bib003'></span>[[#_Bib003|3]],<span id='cite-_Bib004'></span>[[#_Bib004|4]],<span id='cite-_Bib005'></span>[[#_Bib005|5]],<span id='cite-_Bib006'></span>[[#_Bib006|6]],<span id='cite-_Bib007'></span>[[#_Bib007|7]]], it has been fully integrated in the graphical user interface of Iber. This facilitates the model build-up, setup and results visualization converting the new code in a software suite fully operational for all practitioners. | |

| − | The common applications of | + | The common applications of Iber-NNF are the numerical modelling of dense snow avalanches, mine tailings propagation (e.g., after a dam-break), lahars, and hypercongested flows (e.g., wood laden flows). To that end, several rheological models were implemented making Iber-NNF versatile and widen applicable for non-Newtonian shallow flows. |

<span id='_Toc203976057'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976057'></span> | ||

| − | ==2 Graphical user interface of | + | ==2 Graphical user interface of Iber-NNF== |

<span id='_Toc203976058'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976058'></span> | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

===2.1 Generalities=== | ===2.1 Generalities=== | ||

| − | The current version of | + | The current version of Iber-NNF is fully integrated into Iber. Thus, the same properties, options and main workflow used in Iber also applies to Iber-NNF. Only particular characteristics of this module are described below. Further information can be found in the Iber v3 Refence manual [<span id='cite-_Bib008'></span>[[#_Bib008|8]]]. |

| − | It is worth noticing that | + | It is worth noticing that Iber-NNF currently works as an independent hydrodynamic module. None interaction between the rest of calculation modules is permitted due to the kind of flow that Iber-NNF simulate is not water. Future interactions are not discarded. |

<span id='_Toc203976059'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976059'></span> | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

===2.2 Particularities=== | ===2.2 Particularities=== | ||

| − | + | Iber-NNF, as for the rest of modules, must be activated. The activation of Iber-NNF can be done by: | |

:* The menu Iber tools >> Plug-ins… | :* The menu Iber tools >> Plug-ins… | ||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

:* The shortcut [[Image:Draft_Sanz-Ramos_617790713-image1.png|12px]] (located on the left side of the interface, by default) | :* The shortcut [[Image:Draft_Sanz-Ramos_617790713-image1.png|12px]] (located on the left side of the interface, by default) | ||

| − | Once selected ‘NonNewtonian fluid’ as a module, and then applied, the interface will be adapted to this new hydrodynamic module oriented to simulate non–Newtonian flows. The main difference between Iber and | + | Once selected ‘NonNewtonian fluid’ as a module, and then applied, the interface will be adapted to this new hydrodynamic module oriented to simulate non–Newtonian flows. The main difference between Iber and Iber-NNF module relays on the implementation of the flow resistant terms, or rheological model, which have been split in two: |

:* Velocity-dependent, available through Data >> Roughness >> Friction slope… | :* Velocity-dependent, available through Data >> Roughness >> Friction slope… | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

:* Non–Velocity-dependent, available through Data >> Problem data > Non-Newtonian Fluid | :* Non–Velocity-dependent, available through Data >> Problem data > Non-Newtonian Fluid | ||

| − | This separation is a consequence of the numerical scheme developed ad hoc for | + | This separation is a consequence of the numerical scheme developed ad hoc for Iber-NNF. More information is available in Sanz-Ramos et al. [<span id='cite-_Bib002'></span>[[#_Bib002|2]]]. |

<span id='_Toc203976060'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976060'></span> | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

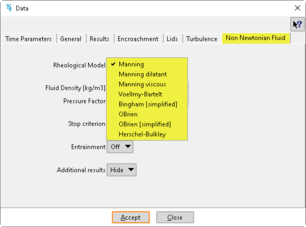

===2.3 Implementation of rheological properties of the fluid=== | ===2.3 Implementation of rheological properties of the fluid=== | ||

| − | As mentioned previously, there is a different way to implement the rheological properties of the fluid in | + | As mentioned previously, there is a different way to implement the rheological properties of the fluid in Iber-NNF. |

<span id='_Toc203976061'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976061'></span> | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

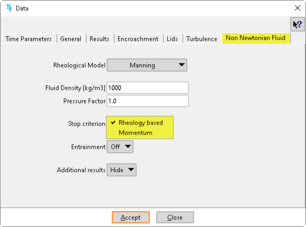

===2.4 Stop criterion=== | ===2.4 Stop criterion=== | ||

| − | The detention of any fluid is consequence of a balance between resistance and driving forces. | + | The detention of any fluid is consequence of a balance between resistance and driving forces. Iber-NNF uses an ad hoc numerical scheme that allows the stop of the fluid according to the fluid properties [<span id='cite-_Bib002'></span>[[#_Bib002|2]]], i.e. the rheological model. |

Another popular numerical model uses a stopping criterion based on controlling the momentum, where the fluid is made to stop when its momentum is lower than a user-defined fraction of its maximum momentum. However, this criterion lacks a physical basis, as the maximum momentum depends on the avalanche’s characteristics at very different location and time than those when it stops. | Another popular numerical model uses a stopping criterion based on controlling the momentum, where the fluid is made to stop when its momentum is lower than a user-defined fraction of its maximum momentum. However, this criterion lacks a physical basis, as the maximum momentum depends on the avalanche’s characteristics at very different location and time than those when it stops. | ||

| − | Both stop criterion are implemented into | + | Both stop criterion are implemented into Iber-NNF; nevertheless, '''we encourage to use the ‘Rheology based’ criterion because is physically based'''. |

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

==3 Governing equations== | ==3 Governing equations== | ||

| − | This section is a brief description of the governing equations of | + | This section is a brief description of the governing equations of Iber-NNF. Further details about this hydrodynamic module and the numerical scheme used to solve the equations can be found in Sanz-Ramos et al. [<span id='cite-_Bib002'></span>[[#_Bib002|2]]]. |

<span id='_Toc203976065'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976065'></span> | ||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

===3.1 2D shallow water equations for non-Newtonian shallow flows=== | ===3.1 2D shallow water equations for non-Newtonian shallow flows=== | ||

| − | + | Iber-NNF solves a particular case of the two-dimensional shallow water equations (2D-SWE), a hyperbolic nonlinear system of three partial differential equations described in Equation <span id='cite-_Ref202869890'></span>[[#_Ref202869890|(1)]]: | |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;border-collapse: collapse;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

| − | <span id='_Hlk123797141'></span>where <math display="inline">h</math> is the water depth, <math display="inline">{q}_{x}</math> and <math display="inline">{q}_{y}</math> are the two components of the specific discharge, <math display="inline">g</math> is the gravitational acceleration, <math display="inline">{S}_{o,x}</math> and <math display="inline">{S}_{o,y}</math> are the two bottom slope components computed as <math display="inline">{\mathit{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{\mathit{\boldsymbol{o}}}=</math><math>{\left( \frac{\partial {z}_{b}}{\partial x},\frac{\partial {z}_{b}}{\partial y}\right) }^{T}</math>, where <math display="inline">{z}_{b}</math> is the bed elevation, and <math display="inline">{S}_{f,x}</math> and <math display="inline">{S}_{f,y}</math> are the two friction slope components computed throughout the rheological model. The friction forces exerted over an inclined bed and the pressure terms can be corrected by replacing the gravity acceleration <math display="inline">g</math> by <math display="inline">{g}^{'}=</math><math>\mathrm{g{cos}^{2}}\,\theta</math> [ | + | <span id='_Hlk123797141'></span>where <math display="inline">h</math> is the water depth, <math display="inline">{q}_{x}</math> and <math display="inline">{q}_{y}</math> are the two components of the specific discharge, <math display="inline">g</math> is the gravitational acceleration, <math display="inline">{S}_{o,x}</math> and <math display="inline">{S}_{o,y}</math> are the two bottom slope components computed as <math display="inline">{\mathit{\boldsymbol{S}}}_{\mathit{\boldsymbol{o}}}=</math><math>{\left( \frac{\partial {z}_{b}}{\partial x},\frac{\partial {z}_{b}}{\partial y}\right) }^{T}</math>, where <math display="inline">{z}_{b}</math> is the bed elevation, and <math display="inline">{S}_{f,x}</math> and <math display="inline">{S}_{f,y}</math> are the two friction slope components computed throughout the rheological model. The friction forces exerted over an inclined bed and the pressure terms can be corrected by replacing the gravity acceleration <math display="inline">g</math> by <math display="inline">{g}^{'}=</math><math>\mathrm{g{cos}^{2}}\,\theta</math> [<span id='cite-_Bib009'></span>[[#_Bib009|9]],<span id='cite-_Bib010'></span>[[#_Bib010|10]],<span id='cite-_Bib011'></span>[[#_Bib011|11]]]. Since the hydrostatic and isotropic pressure distribution cannot be assumed for non-Newtonian flows, as it is done for free surface water flows [<span id='cite-_Bib012'></span>[[#_Bib012|12]]], a factor <math display="inline">{K}_{p}</math> multiplying the pressure terms in the momentum equations was applied [<span id='cite-_Bib013'></span>[[#_Bib013|13]]]. A <math display="inline">{K}_{p}</math> value equal to 1 implies hydrostatic and isotropic pressure distribution. The term <math display="inline">E</math> is entrainment, a process by which solid particles or fragments become incorporated into a moving fluid. The current code partially integrates entrainment formulas based on flow velocity criterion [<span id='cite-_Bib014'></span>[[#_Bib014|14]]], flow height criterion [<span id='cite-_Bib015'></span>[[#_Bib015|15]]] and bed shear stress criterion [<span id='cite-_Bib016'></span>[[#_Bib016|16]]]. The acknowledgment of entrainment is essential for ensuring reliable outcomes and, thus, preventing the underestimation of the volume of snow descending a slope. |

<span id='_Toc203976066'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976066'></span> | ||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

===3.2 Rheological models=== | ===3.2 Rheological models=== | ||

| − | Rheological models to describe both dynamic and static phase of non–Newtonian shallow flows exist for a wide field of applications. In particular, for those related to environmental flows, and more specially for shallow flows, several rheological models have been developed to describe the relationship between the shear stress and the shear rate [17]. | + | Rheological models to describe both dynamic and static phase of non–Newtonian shallow flows exist for a wide field of applications. In particular, for those related to environmental flows, and more specially for shallow flows, several rheological models have been developed to describe the relationship between the shear stress and the shear rate [<span id='cite-_Bib017'></span>[[#_Bib017|17]]]. |

| − | From the simplest Potential law to the full –and complex– Bingham model, several rheological models exist in the literature, the development of each one being oriented to achieve a particular reproduction of a fluid behaviour. The aim of | + | From the simplest Potential law to the full –and complex– Bingham model, several rheological models exist in the literature, the development of each one being oriented to achieve a particular reproduction of a fluid behaviour. The aim of Iber-NNF is not to include as rheological models as possible –or exist–; however, there are some models that, although they have been omitted, can be easily integrated into the proposed numerical scheme by slightly adapting the code. This would allow a broader simulation of the behaviour of non–Newtonian shallow fluids. |

| − | Two hypotheses are usually considered in non-Newtonian shallow flows modelling: ''a monophasic fluid'', in which the fluid is formed by a unique phase where all components are perfectly mixed, and ''shear stress grouping'', in which the effect of different shear stresses are grouped as five components of a single term [18] as follows: | + | Two hypotheses are usually considered in non-Newtonian shallow flows modelling: ''a monophasic fluid'', in which the fluid is formed by a unique phase where all components are perfectly mixed, and ''shear stress grouping'', in which the effect of different shear stresses are grouped as five components of a single term [<span id='cite-_Bib018'></span>[[#_Bib018|18]]] as follows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 167: | Line 167: | ||

where <math display="inline">{\tau }_{d}</math> represents the dispersive term, <math display="inline">{\tau }_{t}</math> the turbulent term, <math display="inline">{\tau }_{v}</math> the viscous term, <math display="inline">{\tau }_{mc}</math> the Mohr–Coulomb terms, and <math display="inline">{\tau }_{c}</math> the cohesive term. In these components, the appropriate rheological model for the particular purpose of each work is obtained by selecting one or several components of Equation <span id='cite-_Ref202871261'></span>[[#_Ref202871261|(2)]]. | where <math display="inline">{\tau }_{d}</math> represents the dispersive term, <math display="inline">{\tau }_{t}</math> the turbulent term, <math display="inline">{\tau }_{v}</math> the viscous term, <math display="inline">{\tau }_{mc}</math> the Mohr–Coulomb terms, and <math display="inline">{\tau }_{c}</math> the cohesive term. In these components, the appropriate rheological model for the particular purpose of each work is obtained by selecting one or several components of Equation <span id='cite-_Ref202871261'></span>[[#_Ref202871261|(2)]]. | ||

| − | + | Iber-NNF integrates several rheological models to represent the resistance forces that act against flow motion of non–Newtonian flows, such as mudflows, debris flows, snow avalanches, lahars, etc. [<span id='cite-_Bib002'></span>[[#_Bib002|2]],<span id='cite-_Bib003'></span>[[#_Bib003|3]],<span id='cite-_Bib004'></span>[[#_Bib004|4]],<span id='cite-_Bib005'></span>[[#_Bib005|5]],<span id='cite-_Bib006'></span>[[#_Bib006|6]],<span id='cite-_Bib007'></span>[[#_Bib007|7]]]. The following sections describe the rheological models implemented expressed in friction slope form ( <math display="inline">\tau =</math><math>\, \rho gh{S}_{f}</math>). | |

<span id='_Toc176677472'></span><span id='_Toc203976067'></span> | <span id='_Toc176677472'></span><span id='_Toc203976067'></span> | ||

| Line 186: | Line 186: | ||

| − | <span id='_Hlk164577165'></span>where <math display="inline">n</math> is the Manning coefficient, <math display="inline">v</math> is the flow velocity and <math display="inline">h</math> is the flow depth. It is related to turbulent friction ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{t}</math>), being utilised by several authors for simulating hyperconcentrated flows [ | + | <span id='_Hlk164577165'></span>where <math display="inline">n</math> is the Manning coefficient, <math display="inline">v</math> is the flow velocity and <math display="inline">h</math> is the flow depth. It is related to turbulent friction ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{t}</math>), being utilised by several authors for simulating hyperconcentrated flows [<span id='cite-_Bib019'></span>[[#_Bib019|19]],<span id='cite-_Bib020'></span>[[#_Bib020|20]],<span id='cite-_Bib021'></span>[[#_Bib021|21]],<span id='cite-_Bib022'></span>[[#_Bib022|22]]]. The unique value for calibration is the Manning coefficient ( <math display="inline">n</math>). |

<span id='_Toc176677473'></span><span id='_Toc203976068'></span> | <span id='_Toc176677473'></span><span id='_Toc203976068'></span> | ||

| Line 192: | Line 192: | ||

====3.2.2 Bingham (simplified)==== | ====3.2.2 Bingham (simplified)==== | ||

| − | Since the proposal of the Bingham | + | Since the proposal of the Bingham rheological model [<span id='cite-_Bib023'></span>[[#_Bib023|23]]], several approaches have been introduced to deal with the difficulties on directly obtaining the shear stress proportional to the flow velocity [<span id='cite-_Bib024'></span>[[#_Bib024|24]]]. Assuming an incompressible and homogeneous flow [<span id='cite-_Bib025'></span>[[#_Bib025|25]],<span id='cite-_Bib026'></span>[[#_Bib026|26]]], the following expression for the viscous ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{v}</math>) and the Mohr–Coulomb ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{mc}</math>) contributions: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 211: | Line 211: | ||

====3.2.3 Voellmy==== | ====3.2.3 Voellmy==== | ||

| − | Voellmy | + | Voellmy [<span id='cite-_Bib027'></span>[[#_Bib027|27]]] presented a rheological model that considers the turbulent ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{t}</math>) and the Mohr–Coulomb ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{mc}</math>) terms as follows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 230: | Line 230: | ||

====3.2.4 Bartelt==== | ====3.2.4 Bartelt==== | ||

| − | Bartelt et al. | + | Bartelt et al. [<span id='cite-_Bib028'></span>[[#_Bib028|28]]] developed a new resistance term related to the cohesion, a physical property of the fluid. This rheological model is commonly used together with the Voellmy model, and expresses as follows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

====3.2.5 Dilatant==== | ====3.2.5 Dilatant==== | ||

| − | <span id='_Hlk164577197'></span>Similarly to the Manning rheological models, and considering constant sediment concentration and uniform flow, Macedonio and Pareschi | + | <span id='_Hlk164577197'></span>Similarly to the Manning rheological models, and considering constant sediment concentration and uniform flow, Macedonio and Pareschi [<span id='cite-_Bib029'></span>[[#_Bib029|29]]] derived the following expression: <math display="inline">\tau =</math><math>{\tau }_{y}+{\mu }_{1}{\left( \frac{dv}{dz}\right) }^{\alpha }</math>, where <math display="inline">{\tau }_{y}</math> is the yield stress, <math display="inline">{\mu }_{1}</math> is a proportionality coefficient and <math display="inline">\alpha</math> is the flow behaviour index. |

When <math display="inline">\alpha</math> = 2 a dilatant flow behaviour is expected: | When <math display="inline">\alpha</math> = 2 a dilatant flow behaviour is expected: | ||

| Line 268: | Line 268: | ||

====3.2.6 Viscous==== | ====3.2.6 Viscous==== | ||

| − | Macedonio and Pareschi | + | Macedonio and Pareschi [<span id='cite-_Bib029'></span>[[#_Bib029|29]]] also presented the application of the Manning equation to viscous flows by particularizing the parameter <math display="inline">\alpha</math> = 1. This allows for the representation of viscous flows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

====3.2.7 O’Brien==== | ====3.2.7 O’Brien==== | ||

| − | On the other hand, O’Brien and Julien | + | On the other hand, O’Brien and Julien [<span id='cite-_Bib030'></span>[[#_Bib030|30]]] derived an expression for the representation of the shear stress of mudflows, being a quadratic equation that integrates the Mohr–Coulomb term ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{mc}</math>), the viscous term ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{v}</math>) and the turbulent term ( <math display="inline">{\tau }_{t}</math>) as follows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 304: | Line 304: | ||

====3.2.8 Herschel-Bulkley==== | ====3.2.8 Herschel-Bulkley==== | ||

| − | The formulation of Herschel and Bulkley | + | The formulation of Herschel and Bulkley [<span id='cite-_Bib031'></span>[[#_Bib031|31]]] is a generalization of various expressions in which, depending on the value of the coefficient <math display="inline">\alpha</math> , dilatant, viscous, plastic, etc. behaviours can be derived. This formula follows the following expression: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 325: | Line 325: | ||

The entrainment is a relevant phenomenon in non-Newtonian flow dynamic modelling because the shear stress between the moving fluid and the terrain generally erode the bottom. This eroded material is then aggregated to the bulk, and might affect it properties (e.g., fluid density) and behaviour. | The entrainment is a relevant phenomenon in non-Newtonian flow dynamic modelling because the shear stress between the moving fluid and the terrain generally erode the bottom. This eroded material is then aggregated to the bulk, and might affect it properties (e.g., fluid density) and behaviour. | ||

| − | The effects of entrainment extend beyond altering mass and energy balances. Predicted velocities along the bulk path and the kinetic energy upon reaching the runout zone are also affected. These changes directly influence runout distances and have substantial implications for hazard and risk mapping. Particularly for snow avalanche modelling, entrainment leads to higher predicted flow heights and volumes of avalanches [15, | + | The effects of entrainment extend beyond altering mass and energy balances. Predicted velocities along the bulk path and the kinetic energy upon reaching the runout zone are also affected. These changes directly influence runout distances and have substantial implications for hazard and risk mapping. Particularly for snow avalanche modelling, entrainment leads to higher predicted flow heights and volumes of avalanches [<span id='cite-_Bib015'></span>[[#_Bib015|15]],<span id='cite-_Bib032'></span>[[#_Bib032|32]],<span id='cite-_Bib033'></span>[[#_Bib033|33]],<span id='cite-_Bib034'></span>[[#_Bib034|34]],<span id='cite-_Bib035'></span>[[#_Bib035|35]]]. |

Accurate predictions are crucial for designing infrastructure, such as barriers or dams, as incorrect estimations may result in inadequate protection or increased costs. Therefore, precise consideration of entrainment is essential for determining runout distances and optimizing infrastructure design to mitigate hazards effectively. | Accurate predictions are crucial for designing infrastructure, such as barriers or dams, as incorrect estimations may result in inadequate protection or increased costs. Therefore, precise consideration of entrainment is essential for determining runout distances and optimizing infrastructure design to mitigate hazards effectively. | ||

| Line 333: | Line 333: | ||

====3.3.1 Velocity model==== | ====3.3.1 Velocity model==== | ||

| − | This is a simple model that considers mass entrainment as function of the flow velocity. In contrast with another popular model, | + | This is a simple model that considers mass entrainment as function of the flow velocity. In contrast with another popular model, Iber-NNF considers entrainment when the flow velocity is greater than a threshold ( <math display="inline">{u}_{crit}</math>). |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 352: | Line 352: | ||

====3.3.2 Height model==== | ====3.3.2 Height model==== | ||

| − | In this model, the entrainment depends on the load of the underlying snow cover as long as its height reaches a fixed minimum value ( <math display="inline">{h}_{crit}</math>); otherwise, the entrainment will be considered inexistent [15]. This model also integrates an upper limit for the height based on the dry friction law to avoid the dry friction increasing limitless [36]: | + | In this model, the entrainment depends on the load of the underlying snow cover as long as its height reaches a fixed minimum value ( <math display="inline">{h}_{crit}</math>); otherwise, the entrainment will be considered inexistent [<span id='cite-_Bib015'></span>[[#_Bib015|15]]]. This model also integrates an upper limit for the height based on the dry friction law to avoid the dry friction increasing limitless [<span id='cite-_Bib036'></span>[[#_Bib036|36]]]: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 382: | Line 382: | ||

====3.3.3 Squared velocity model==== | ====3.3.3 Squared velocity model==== | ||

| − | This equation is similar to the velocity model although the entrainment rate is considered to vary with the squared velocity of the avalanche [15]: | + | This equation is similar to the velocity model although the entrainment rate is considered to vary with the squared velocity of the avalanche [<span id='cite-_Bib015'></span>[[#_Bib015|15]]]: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 414: | Line 414: | ||

| − | where <math display="inline">{K}_{\tau }</math> is the entrainment rate, which a range from 1.5 to 12·10<sup>-6</sup> m·s<sup>-1</sup>·Pa<sup>-1</sup> is proposed [16]. | + | where <math display="inline">{K}_{\tau }</math> is the entrainment rate, which a range from 1.5 to 12·10<sup>-6</sup> m·s<sup>-1</sup>·Pa<sup>-1</sup> is proposed [<span id='cite-_Bib016'></span>[[#_Bib016|16]]]. |

<span id='_Toc203976080'></span> | <span id='_Toc203976080'></span> | ||

| Line 420: | Line 420: | ||

==4 Results== | ==4 Results== | ||

| − | As in the hydrodynamic module for water flows, | + | As in the hydrodynamic module for water flows, Iber-NNF also integrates flow depths, velocities, elevation, etc. However, particular results can be activated through Data >> Problem data >> NonNewtonian fluid tab, such as extra topographical information (terrain slope) and impact forces [<span id='cite-_Bib037'></span>[[#_Bib037|37]],<span id='cite-_Bib038'></span>[[#_Bib038|38]]]. This results essentially applies for dense snow avalanche modelling, but they are not limited to. |

| − | Particularly for impact forces, | + | Particularly for impact forces, Iber-NNF calculates the dynamic pressure (Equation <span id='cite-_Ref202886400'></span>[[#_Ref202886400|(16)]]), the peak dynamic pressure (Equation <span id='cite-_Ref202886402'></span>[[#_Ref202886402|(17)]]) and its maximus as follows: |

{| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | {| class="formulaSCP" style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;width: 100%;text-align: center;" | ||

| Line 452: | Line 452: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib001'></span> | ||

[1] E. Bladé, L. Cea, G. Corestein, E. Escolano, J. Puertas, E. Vázquez-Cendón, J. Dolz, A. Coll, Iber: herramienta de simulación numérica del flujo en ríos, Rev. Int. Métodos Numéricos Para Cálculo y Diseño En Ing. 30 (2014) 1–10. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rimni.2012.07.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rimni.2012.07.004.] | [1] E. Bladé, L. Cea, G. Corestein, E. Escolano, J. Puertas, E. Vázquez-Cendón, J. Dolz, A. Coll, Iber: herramienta de simulación numérica del flujo en ríos, Rev. Int. Métodos Numéricos Para Cálculo y Diseño En Ing. 30 (2014) 1–10. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rimni.2012.07.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rimni.2012.07.004.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib002'></span> | ||

[2] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, P. Oller, G. Furdada, Numerical modelling of dense snow avalanches with a well-balanced scheme based on the 2D shallow water equations, J. Glaciol. (2023) 1–17. [https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.48. https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.48.] | [2] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, P. Oller, G. Furdada, Numerical modelling of dense snow avalanches with a well-balanced scheme based on the 2D shallow water equations, J. Glaciol. (2023) 1–17. [https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.48. https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.48.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib003'></span> | ||

[3] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, El rol de los términos de fricción y cohesión en la modelización bidimensional de fluidos no Newtonianos: avalanchas de nieve densa, Ing. Del Agua. 27 (2023) 295–310. [https://doi.org/10.4995/ia.2023.20080. https://doi.org/10.4995/ia.2023.20080.] | [3] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, El rol de los términos de fricción y cohesión en la modelización bidimensional de fluidos no Newtonianos: avalanchas de nieve densa, Ing. Del Agua. 27 (2023) 295–310. [https://doi.org/10.4995/ia.2023.20080. https://doi.org/10.4995/ia.2023.20080.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib004'></span> | ||

[4] M. Sanz-Ramos, C.A. Andrade, P. Oller, G. Furdada, E. Bladé, E. Martínez-Gomariz, Reconstructing the Snow Avalanche of Coll de Pal 2018 (SE Pyrenees), GeoHazards. 2 (2021) 196–211. [https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards2030011. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards2030011.] | [4] M. Sanz-Ramos, C.A. Andrade, P. Oller, G. Furdada, E. Bladé, E. Martínez-Gomariz, Reconstructing the Snow Avalanche of Coll de Pal 2018 (SE Pyrenees), GeoHazards. 2 (2021) 196–211. [https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards2030011. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards2030011.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib005'></span> | ||

[5] V. Ruiz-Villanueva, B. Mazzorana, E. Bladé, L. Bürkli, P. Iribarren-Anacona, L. Mao, F. Nakamura, D. Ravazzolo, D. Rickenmann, M. Sanz-Ramos, M. Stoffel, E. Wohl, Characterization of wood-laden flows in rivers, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms. 44 (2019) 1694–1709. [https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4603. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4603.] | [5] V. Ruiz-Villanueva, B. Mazzorana, E. Bladé, L. Bürkli, P. Iribarren-Anacona, L. Mao, F. Nakamura, D. Ravazzolo, D. Rickenmann, M. Sanz-Ramos, M. Stoffel, E. Wohl, Characterization of wood-laden flows in rivers, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms. 44 (2019) 1694–1709. [https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4603. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4603.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib006'></span> | ||

[6] M. Sanz-Ramos, J.J. Vales-Bravo, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, Reconstructing the spill propagation of the Aznalcóllar mine disaster, Mine Water Environ. 43 (2024). [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-01000-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-01000-5.] | [6] M. Sanz-Ramos, J.J. Vales-Bravo, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, Reconstructing the spill propagation of the Aznalcóllar mine disaster, Mine Water Environ. 43 (2024). [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-01000-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-01000-5.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib007'></span> | ||

[7] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, T. Dysarz, Extension of Iber for Simulating Non–Newtonian Shallow Flows: Mine-Tailings Spill Propagation Modelling, Water. 16 (2024) 2039. [https://doi.org/10.3390/w16142039. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16142039.] | [7] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, T. Dysarz, Extension of Iber for Simulating Non–Newtonian Shallow Flows: Mine-Tailings Spill Propagation Modelling, Water. 16 (2024) 2039. [https://doi.org/10.3390/w16142039. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16142039.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib008'></span> | ||

[8] M. Sanz-Ramos, L. Cea, E. Bladé, D. López-Gómez, E. Sañudo, G. Corestein, G. García-Alén, J. Aragón-Hernández, Iber v3. Reference manual and user’s interface of the new implementations, CIMNE, 2022. [https://doi.org/10.23967/iber.2022.01. https://doi.org/10.23967/iber.2022.01.] | [8] M. Sanz-Ramos, L. Cea, E. Bladé, D. López-Gómez, E. Sañudo, G. Corestein, G. García-Alén, J. Aragón-Hernández, Iber v3. Reference manual and user’s interface of the new implementations, CIMNE, 2022. [https://doi.org/10.23967/iber.2022.01. https://doi.org/10.23967/iber.2022.01.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib009'></span> | ||

[9] Y. Ni, Z. Cao, Q. Liu, Mathematical modeling of shallow-water flows on steep slopes, J. Hydrol. Hydromechanics. 67 (2019) 252–259. [https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0012. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0012.] | [9] Y. Ni, Z. Cao, Q. Liu, Mathematical modeling of shallow-water flows on steep slopes, J. Hydrol. Hydromechanics. 67 (2019) 252–259. [https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0012. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0012.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib010'></span> | ||

[10] A. Maranzoni, M. Tomirotti, New formulation of the two-dimensional steep-slope shallow water equations. Part I: Theory and analysis, Adv. Water Resour. 166 (2022) 104255. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104255.] | [10] A. Maranzoni, M. Tomirotti, New formulation of the two-dimensional steep-slope shallow water equations. Part I: Theory and analysis, Adv. Water Resour. 166 (2022) 104255. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104255.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib011'></span> | ||

[11] D. Zugliani, G. Rosatti, TRENT2D❄: An accurate numerical approach to the simulation of two-dimensional dense snow avalanches in global coordinate systems, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 190 (2021) 103343. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103343.] | [11] D. Zugliani, G. Rosatti, TRENT2D❄: An accurate numerical approach to the simulation of two-dimensional dense snow avalanches in global coordinate systems, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 190 (2021) 103343. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103343.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib012'></span> | ||

[12] V. Te Chow, Open-Channel Hydraulics, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc. New York, USA, 1959. | [12] V. Te Chow, Open-Channel Hydraulics, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc. New York, USA, 1959. | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib013'></span> | ||

[13] S.B. Savage, K. Hutter, The motion of a finite mass of granular material down a rough incline, J. Fluid Mech. 199 (1989) 177–215. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089000340. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089000340.] | [13] S.B. Savage, K. Hutter, The motion of a finite mass of granular material down a rough incline, J. Fluid Mech. 199 (1989) 177–215. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089000340. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089000340.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib014'></span> | ||

[14] M. Christen, J. Kowalski, P. Bartelt, RAMMS: Numerical simulation of dense snow avalanches in three-dimensional terrain, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 63 (2010) 1–14. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2010.04.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2010.04.005.] | [14] M. Christen, J. Kowalski, P. Bartelt, RAMMS: Numerical simulation of dense snow avalanches in three-dimensional terrain, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 63 (2010) 1–14. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2010.04.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2010.04.005.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib015'></span> | ||

[15] M.E. Eglit, K.S. Demidov, Mathematical modeling of snow entrainment in avalanche motion, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 43 (2005) 10–23. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2005.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2005.03.005.] | [15] M.E. Eglit, K.S. Demidov, Mathematical modeling of snow entrainment in avalanche motion, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 43 (2005) 10–23. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2005.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2005.03.005.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib016'></span> | ||

[16] J. Castelló, Enhancement and application of numerical methods for snow avalanche modelling, Master thesis. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain, 2020. | [16] J. Castelló, Enhancement and application of numerical methods for snow avalanche modelling, Master thesis. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain, 2020. | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib017'></span> | ||

[17] K. Msheik, Non-Newtonian Fluids: Modeling and Well-Posedness, Universite Grenoble Alpes, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2020. [https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03099969. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03099969.] | [17] K. Msheik, Non-Newtonian Fluids: Modeling and Well-Posedness, Universite Grenoble Alpes, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2020. [https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03099969. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03099969.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib018'></span> | ||

[18] P.Y. Julien, C.A. León, Mudfloods, mudflows and debrisflows, classification in rheology and structural design, in: Int. Work. Debris Flow Disaster 27 November–1 December 1999, 2000: pp. 1–15. | [18] P.Y. Julien, C.A. León, Mudfloods, mudflows and debrisflows, classification in rheology and structural design, in: Int. Work. Debris Flow Disaster 27 November–1 December 1999, 2000: pp. 1–15. | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib019'></span> | ||

[19] T. Takahashi, Debris flow: mechanics and hazard mitigation, in: ROC-JAPAN Jt. Semin. Mul- Tiple Hazards Mitig., National Taiwan Univerisity, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC, 1985: pp. 1075–1092. | [19] T. Takahashi, Debris flow: mechanics and hazard mitigation, in: ROC-JAPAN Jt. Semin. Mul- Tiple Hazards Mitig., National Taiwan Univerisity, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC, 1985: pp. 1075–1092. | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib020'></span> | ||

[20] A. Laenen, R.P. Hansen, Simulation of three lahars in the Mount St. Helens area, Washington, using a one-dimensional, unsteady-state streamflow model, 1988. [https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/wri884004. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/wri884004.] | [20] A. Laenen, R.P. Hansen, Simulation of three lahars in the Mount St. Helens area, Washington, using a one-dimensional, unsteady-state streamflow model, 1988. [https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/wri884004. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/wri884004.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib021'></span> | ||

[21] M. Syarifuddin, S. Oishi, R.I. Hapsari, D. Legono, Empirical model for remote monitoring of rain-triggered lahar at Mount Merapi, J. Japan Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 (Hydraulic Eng. 74 (2018) I_1483-I_1488. [https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.74.I_1483. https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.74.I_1483.] | [21] M. Syarifuddin, S. Oishi, R.I. Hapsari, D. Legono, Empirical model for remote monitoring of rain-triggered lahar at Mount Merapi, J. Japan Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 (Hydraulic Eng. 74 (2018) I_1483-I_1488. [https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.74.I_1483. https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.74.I_1483.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib022'></span> | ||

[22] A.R. Darnell, J.C. Phillips, J. Barclay, R.A. Herd, A.A. Lovett, P.D. Cole, Developing a simplified geographical information system approach to dilute lahar modelling for rapid hazard assessment, Bull. Volcanol. 75 (2013) 713. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-013-0713-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-013-0713-6.] | [22] A.R. Darnell, J.C. Phillips, J. Barclay, R.A. Herd, A.A. Lovett, P.D. Cole, Developing a simplified geographical information system approach to dilute lahar modelling for rapid hazard assessment, Bull. Volcanol. 75 (2013) 713. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-013-0713-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-013-0713-6.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib023'></span> | ||

[23] E.C. Bingham, An investigation of the laws of plastic flow, Bull. Bur. Stand. 13 (1916) 309–353. [https://doi.org/10.6028/bulletin.304. https://doi.org/10.6028/bulletin.304.] | [23] E.C. Bingham, An investigation of the laws of plastic flow, Bull. Bur. Stand. 13 (1916) 309–353. [https://doi.org/10.6028/bulletin.304. https://doi.org/10.6028/bulletin.304.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib024'></span> | ||

[24] M. Pastor, B. Haddad, G. Sorbino, S. Cuomo, V. Drempetic, A depth‐integrated, coupled SPH model for flow‐like landslides and related phenomena, Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 33 (2009) 143–172. [https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.705. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.705.] | [24] M. Pastor, B. Haddad, G. Sorbino, S. Cuomo, V. Drempetic, A depth‐integrated, coupled SPH model for flow‐like landslides and related phenomena, Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 33 (2009) 143–172. [https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.705. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.705.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib025'></span> | ||

[25] H. Chen, C.F. Lee, Runout Analysis of Slurry Flows with Bingham Model, J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 128 (2002) 1032–1042. [https://doi.org/10.1061/ https://doi.org/10.1061/](ASCE)1090-0241(2002)128:12(1032). | [25] H. Chen, C.F. Lee, Runout Analysis of Slurry Flows with Bingham Model, J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 128 (2002) 1032–1042. [https://doi.org/10.1061/ https://doi.org/10.1061/](ASCE)1090-0241(2002)128:12(1032). | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib026'></span> | ||

[26] D. Naef, D. Rickenmann, P. Rutschmann, B.W. McArdell, Comparison of flow resistance relations for debris flows using a one-dimensional finite element simulation model, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 6 (2006) 155–165. [https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-155-2006. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-155-2006.] | [26] D. Naef, D. Rickenmann, P. Rutschmann, B.W. McArdell, Comparison of flow resistance relations for debris flows using a one-dimensional finite element simulation model, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 6 (2006) 155–165. [https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-155-2006. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-155-2006.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib027'></span> | ||

[27] A. Voellmy, Über die Zerstörungskraft von Lawinen, Schweizerische Bauzeitung. 73 (1955) 15. [https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-61891. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-61891.] | [27] A. Voellmy, Über die Zerstörungskraft von Lawinen, Schweizerische Bauzeitung. 73 (1955) 15. [https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-61891. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-61891.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib028'></span> | ||

[28] P. Bartelt, C.V. Valero, T. Feistl, M. Christen, Y. Bühler, O. Buser, Modelling cohesion in snow avalanche flow, J. Glaciol. 61 (2015) 837–850. [https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126. https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126.] | [28] P. Bartelt, C.V. Valero, T. Feistl, M. Christen, Y. Bühler, O. Buser, Modelling cohesion in snow avalanche flow, J. Glaciol. 61 (2015) 837–850. [https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126. https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib029'></span> | ||

[29] G. Macedonio, M.T.T. Pareschi, Numerical simulation of some lahars from Mount St. Helens, J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 54 (1992) 65–80. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273 https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273](92)90115-T. | [29] G. Macedonio, M.T.T. Pareschi, Numerical simulation of some lahars from Mount St. Helens, J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 54 (1992) 65–80. [https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273 https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273](92)90115-T. | ||

| − | [30] J.S. O’Brien, P.Y. Julien, Laboratory Analysis of Mudflow Properties, J. Hydraul. Eng. 114 (1988) 877–887. [https://doi.org/10.1061/ https://doi.org/10.1061/ | + | <span id='_Bib030'></span> |

| + | [30] J.S. O’Brien, P.Y. Julien, Laboratory Analysis of Mudflow Properties, J. Hydraul. Eng. 114 (1988) 877–887. [https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1988)114:8(877) https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1988)114:8(877)]. | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib031'></span> | ||

[31] W.H. Herschel, R. Bulkley, Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi-Benzollösungen, Kolloid-Zeitschrift. 39 (1926) 291–300. [https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01432034. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01432034.] | [31] W.H. Herschel, R. Bulkley, Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi-Benzollösungen, Kolloid-Zeitschrift. 39 (1926) 291–300. [https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01432034. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01432034.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib032'></span> | ||

[32] L. Dreier, Y. Bühler, W. Steinkogler, T. Feistl, M. Christen, P. Bartelt, Modelling Small and Frequent Avalanches, in: Int. Snow Sci. Work. 2014 Proc., 29 Sep - 3 Oct, Banff, Canada, 2014: p. 8. [http://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item/2128. http://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item/2128.] | [32] L. Dreier, Y. Bühler, W. Steinkogler, T. Feistl, M. Christen, P. Bartelt, Modelling Small and Frequent Avalanches, in: Int. Snow Sci. Work. 2014 Proc., 29 Sep - 3 Oct, Banff, Canada, 2014: p. 8. [http://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item/2128. http://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item/2128.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib033'></span> | ||

[33] V. Medina, M. Hürlimann, A. Bateman, Application of FLATModel, a 2D finite volume code, to debris flows in the northeastern part of the Iberian Peninsula, Landslides. 5 (2008) 127–142. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-007-0102-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-007-0102-3.] | [33] V. Medina, M. Hürlimann, A. Bateman, Application of FLATModel, a 2D finite volume code, to debris flows in the northeastern part of the Iberian Peninsula, Landslides. 5 (2008) 127–142. [https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-007-0102-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-007-0102-3.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib034'></span> | ||

[34] M. Eglit, A. Yakubenko, J. Zayko, A Review of Russian Snow Avalanche Models—From Analytical Solutions to Novel 3D Models, Geosciences. 10 (2020) 77. [https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10020077. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10020077.] | [34] M. Eglit, A. Yakubenko, J. Zayko, A Review of Russian Snow Avalanche Models—From Analytical Solutions to Novel 3D Models, Geosciences. 10 (2020) 77. [https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10020077. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10020077.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib035'></span> | ||

[35] M. Garcia, G. Parker, Entrainment of Bed Sediment into Suspension, J. Hydraul. Eng. 117 (1991) 414–435. [https://doi.org/10.1061/ https://doi.org/10.1061/](ASCE)0733-9429(1991)117:4(414). | [35] M. Garcia, G. Parker, Entrainment of Bed Sediment into Suspension, J. Hydraul. Eng. 117 (1991) 414–435. [https://doi.org/10.1061/ https://doi.org/10.1061/](ASCE)0733-9429(1991)117:4(414). | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib036'></span> | ||

[36] P. Bartelt, B. Salm, U. Gruber, Calculating dense-snow avalanche runout using a Voellmy-fluid model with active/passive longitudinal straining, J. Glaciol. 45 (1999) 242–254. [https://doi.org/10.3189/s002214300000174x. https://doi.org/10.3189/s002214300000174x.] | [36] P. Bartelt, B. Salm, U. Gruber, Calculating dense-snow avalanche runout using a Voellmy-fluid model with active/passive longitudinal straining, J. Glaciol. 45 (1999) 242–254. [https://doi.org/10.3189/s002214300000174x. https://doi.org/10.3189/s002214300000174x.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib037'></span> | ||

[37] C.J. Keylock, M. Barbolini, Snow avalanche impact pressure - vulnerability relations for use in risk assessment, Can. Geotech. J. 38 (2011) 227–238. [https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-100. https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-100.] | [37] C.J. Keylock, M. Barbolini, Snow avalanche impact pressure - vulnerability relations for use in risk assessment, Can. Geotech. J. 38 (2011) 227–238. [https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-100. https://doi.org/10.1139/t00-100.] | ||

| + | <span id='_Bib038'></span> | ||

[38] F. Rudolf-Miklau, S. Sauermoser, A.I. Mears, F. Rudolf‐Miklau, S. Sauermoser, A.I. Mears, The Technical Avalanche Protection Handbook, Wiley, Berlin, Germany, 2014. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9783433603840. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783433603840.] | [38] F. Rudolf-Miklau, S. Sauermoser, A.I. Mears, F. Rudolf‐Miklau, S. Sauermoser, A.I. Mears, The Technical Avalanche Protection Handbook, Wiley, Berlin, Germany, 2014. [https://doi.org/10.1002/9783433603840. https://doi.org/10.1002/9783433603840.] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:48, 22 July 2025

Abstract

Iber is a two-dimensional hydraulic model for the simulation of free surface flow in rivers and estuaries, and the simulation of environmental processes in fluvial hydraulics. Since the release of the first version of Iber, which included a hydrodynamic calculation engine fully coupled with sediment transport processes and turbulence, it has evolved to become a free surface flow modelling tool for highly complex environmental processes. This document presents the developments made for version 3, specifically, for the new calculation module for the simulation of shallow non-Newtonian flows called Iber-NNF. The shallow water equations are solved using an ad-hoc numerical scheme focused on the simulation of this type of flow in nature (e.g., steep slopes, irregular geometries). The graphical user interface (GUI) has been adapted to the module's new features to achieve a simple and user-friendly workflow.

Keywords: non-Newtonian flows, snow avalanches, mud/debris flows, hypercongested flows, Iber

Resumen

Iber es un modelo numérico bidimensional de simulación de flujo turbulento en lámina libre en régimen no-permanente, y de procesos medioambientales en hidráulica fluvial. Desde el lanzamiento de la primera versión, que incluía un motor de cálculo hidrodinámico para completamente acoplado con procesos de transporte de sedimento y turbulencia, Iber ha ido evolucionando hasta convertirse en una herramienta de modelización de flujo de agua en lámina libre de procesos ambientales de elevada complejidad. En este documento se presentan los desarrollos realizados para la versión 3, concretamente para el nuevo módulo de cálculo para la simulación de flujos no-newtonianos someros denominado Iber-NNF. La resolución de las ecuaciones de aguas someras se lleva a cabo mediante un esquema numérico propio enfocado a la simulación de este tipo de flujos en la naturaleza (p.ej., pendientes elevadas, geometrías irregulares). La interfaz gráfica de usuario (GUI) se ha adaptado para con las nuevas características del módulo con el fin de obtener un flujo de trabajo sencillo y amigable.

Palabras clave: flujos no-newtonianos, aludes, flujo de lodos/escombros, flujos hipercongestionados, Iber

1 Introduction

Numerical modelling of natural phenomena, particularly weather-related which are the 90 % of global disasters, is essential to analyse and predict hazardous situations for the people, the economy and the environment. The evolution of these numerical tools, from simple one-dimensional to complex three-dimensional models, to simulate hydrological hazards like floods, mass movements, and avalanches is challenging, especially those in which the fluid can be characterized as non–Newtonian flows.

Iber-NNF was developed, based on Iber [1], as a depth-averaged two-dimensional hydrodynamic numerical tool to simulate non–Newtonian shallow flows. To that end, a particular numerical scheme based on an upwind discretisation to ensure a proper balance between the non–velocity-dependent terms of the shear stresses and the pressure forces has been developed [2]. This ensures the stop of the fluid according to the rheological properties of the fluid, even in steep slopes and complex geometries. The code besides being validated and applied in theoretical, analytical, and real situations of common and non–common non–Newtonian shallow flows [2,3,4,5,6,7], it has been fully integrated in the graphical user interface of Iber. This facilitates the model build-up, setup and results visualization converting the new code in a software suite fully operational for all practitioners.

The common applications of Iber-NNF are the numerical modelling of dense snow avalanches, mine tailings propagation (e.g., after a dam-break), lahars, and hypercongested flows (e.g., wood laden flows). To that end, several rheological models were implemented making Iber-NNF versatile and widen applicable for non-Newtonian shallow flows.

2 Graphical user interface of Iber-NNF

2.1 Generalities

The current version of Iber-NNF is fully integrated into Iber. Thus, the same properties, options and main workflow used in Iber also applies to Iber-NNF. Only particular characteristics of this module are described below. Further information can be found in the Iber v3 Refence manual [8].

It is worth noticing that Iber-NNF currently works as an independent hydrodynamic module. None interaction between the rest of calculation modules is permitted due to the kind of flow that Iber-NNF simulate is not water. Future interactions are not discarded.

2.2 Particularities

Iber-NNF, as for the rest of modules, must be activated. The activation of Iber-NNF can be done by:

- The menu Iber tools >> Plug-ins…

Once selected ‘NonNewtonian fluid’ as a module, and then applied, the interface will be adapted to this new hydrodynamic module oriented to simulate non–Newtonian flows. The main difference between Iber and Iber-NNF module relays on the implementation of the flow resistant terms, or rheological model, which have been split in two:

- Velocity-dependent, available through Data >> Roughness >> Friction slope…

- Non–Velocity-dependent, available through Data >> Problem data > Non-Newtonian Fluid

This separation is a consequence of the numerical scheme developed ad hoc for Iber-NNF. More information is available in Sanz-Ramos et al. [2].

2.3 Implementation of rheological properties of the fluid

As mentioned previously, there is a different way to implement the rheological properties of the fluid in Iber-NNF.

2.3.1 Velocity-dependent terms

Velocity-dependent terms of the rheological model must be implemented as a friction slope at each mesh element (Data >> Roughness >> Friction slope…). These parameters can be defined manually or automatically (by a raster file), and are associated to the concept known as ‘Land use’; thus, they can vary spatially.

|

|

| (a) | (b) |

Fig. 1. Land uses windows: (a) database of land uses for non-Newtonian flows; (b) list of velocity-dependent parameters according to each rheological model.

2.3.2 Non–Velocity-dependent terms

By contrast, non–Velocity-dependent terms can be interpreted as a characteristic of the fluid; thus, they cannot vary spatially –perhaps temporally– and they must be defined as a constant value (Data >> Problem data > Non Newtonian Fluid). This is the case of the flow density, the pressure factor, the Coulomb friction coefficient, the yield stress, etc.

Fig. 2. Problem data window. Non-Newtonian fluid tab allows the selection of the rheological model to be used and other properties.

2.4 Stop criterion

The detention of any fluid is consequence of a balance between resistance and driving forces. Iber-NNF uses an ad hoc numerical scheme that allows the stop of the fluid according to the fluid properties [2], i.e. the rheological model.

Another popular numerical model uses a stopping criterion based on controlling the momentum, where the fluid is made to stop when its momentum is lower than a user-defined fraction of its maximum momentum. However, this criterion lacks a physical basis, as the maximum momentum depends on the avalanche’s characteristics at very different location and time than those when it stops.

Both stop criterion are implemented into Iber-NNF; nevertheless, we encourage to use the ‘Rheology based’ criterion because is physically based.

Fig. 3. Problem data window. Selection of the stop criterion.

3 Governing equations

This section is a brief description of the governing equations of Iber-NNF. Further details about this hydrodynamic module and the numerical scheme used to solve the equations can be found in Sanz-Ramos et al. [2].

3.1 2D shallow water equations for non-Newtonian shallow flows

Iber-NNF solves a particular case of the two-dimensional shallow water equations (2D-SWE), a hyperbolic nonlinear system of three partial differential equations described in Equation (1):

|

|

(1) |

where is the water depth, and are the two components of the specific discharge, is the gravitational acceleration, and are the two bottom slope components computed as , where is the bed elevation, and and are the two friction slope components computed throughout the rheological model. The friction forces exerted over an inclined bed and the pressure terms can be corrected by replacing the gravity acceleration by [9,10,11]. Since the hydrostatic and isotropic pressure distribution cannot be assumed for non-Newtonian flows, as it is done for free surface water flows [12], a factor multiplying the pressure terms in the momentum equations was applied [13]. A value equal to 1 implies hydrostatic and isotropic pressure distribution. The term is entrainment, a process by which solid particles or fragments become incorporated into a moving fluid. The current code partially integrates entrainment formulas based on flow velocity criterion [14], flow height criterion [15] and bed shear stress criterion [16]. The acknowledgment of entrainment is essential for ensuring reliable outcomes and, thus, preventing the underestimation of the volume of snow descending a slope.

3.2 Rheological models

Rheological models to describe both dynamic and static phase of non–Newtonian shallow flows exist for a wide field of applications. In particular, for those related to environmental flows, and more specially for shallow flows, several rheological models have been developed to describe the relationship between the shear stress and the shear rate [17].

From the simplest Potential law to the full –and complex– Bingham model, several rheological models exist in the literature, the development of each one being oriented to achieve a particular reproduction of a fluid behaviour. The aim of Iber-NNF is not to include as rheological models as possible –or exist–; however, there are some models that, although they have been omitted, can be easily integrated into the proposed numerical scheme by slightly adapting the code. This would allow a broader simulation of the behaviour of non–Newtonian shallow fluids.

Two hypotheses are usually considered in non-Newtonian shallow flows modelling: a monophasic fluid, in which the fluid is formed by a unique phase where all components are perfectly mixed, and shear stress grouping, in which the effect of different shear stresses are grouped as five components of a single term [18] as follows:

|

|

(2) |

where represents the dispersive term, the turbulent term, the viscous term, the Mohr–Coulomb terms, and the cohesive term. In these components, the appropriate rheological model for the particular purpose of each work is obtained by selecting one or several components of Equation (2).

Iber-NNF integrates several rheological models to represent the resistance forces that act against flow motion of non–Newtonian flows, such as mudflows, debris flows, snow avalanches, lahars, etc. [2,3,4,5,6,7]. The following sections describe the rheological models implemented expressed in friction slope form ( ).

3.2.1 Manning

The Manning rheological model, an empirical equation widely utilised in hydraulics and hydrology, applies to uniform flow in open channels and is a function of the channel velocity, flow area and channel slope:

|

|

(3) |

where is the Manning coefficient, is the flow velocity and is the flow depth. It is related to turbulent friction ( ), being utilised by several authors for simulating hyperconcentrated flows [19,20,21,22]. The unique value for calibration is the Manning coefficient ( ).

3.2.2 Bingham (simplified)

Since the proposal of the Bingham rheological model [23], several approaches have been introduced to deal with the difficulties on directly obtaining the shear stress proportional to the flow velocity [24]. Assuming an incompressible and homogeneous flow [25,26], the following expression for the viscous ( ) and the Mohr–Coulomb ( ) contributions:

|

|

(4) |

where is the yield stress, is the fluid density, is the flow depth, is the fluid viscosity, is the flow velocity, and is the gravitational acceleration.

3.2.3 Voellmy

Voellmy [27] presented a rheological model that considers the turbulent ( ) and the Mohr–Coulomb ( ) terms as follows:

|

|

(5) |

where is the turbulent friction coefficient, is the Coulomb friction coefficient, is the flow depth and is the flow velocity.

3.2.4 Bartelt

Bartelt et al. [28] developed a new resistance term related to the cohesion, a physical property of the fluid. This rheological model is commonly used together with the Voellmy model, and expresses as follows:

|

|

(6) |

where is the fluid density, is the gravitational acceleration, is the flow depth, is the cohesion, and is the Coulomb friction coefficient.

3.2.5 Dilatant

Similarly to the Manning rheological models, and considering constant sediment concentration and uniform flow, Macedonio and Pareschi [29] derived the following expression: , where is the yield stress, is a proportionality coefficient and is the flow behaviour index.

When = 2 a dilatant flow behaviour is expected:

|

|

(7) |

3.2.6 Viscous

Macedonio and Pareschi [29] also presented the application of the Manning equation to viscous flows by particularizing the parameter = 1. This allows for the representation of viscous flows:

|

|

(8) |

3.2.7 O’Brien

On the other hand, O’Brien and Julien [30] derived an expression for the representation of the shear stress of mudflows, being a quadratic equation that integrates the Mohr–Coulomb term ( ), the viscous term ( ) and the turbulent term ( ) as follows:

|

|

(9) |

where is the yield stress, is the fluid density, is the gravitational acceleration, is the flow depth, is a resistance parameter, is the flow viscosity, is the flow velocity, and is the Manning coefficient.

3.2.8 Herschel-Bulkley

The formulation of Herschel and Bulkley [31] is a generalization of various expressions in which, depending on the value of the coefficient , dilatant, viscous, plastic, etc. behaviours can be derived. This formula follows the following expression:

|

|

(10) |

where is the yield stress, is the fluid density, is the gravitational acceleration, is the flow depth, is a consistency parameter, and is the flow velocity.

3.3 Entrainment

The entrainment is a relevant phenomenon in non-Newtonian flow dynamic modelling because the shear stress between the moving fluid and the terrain generally erode the bottom. This eroded material is then aggregated to the bulk, and might affect it properties (e.g., fluid density) and behaviour.

The effects of entrainment extend beyond altering mass and energy balances. Predicted velocities along the bulk path and the kinetic energy upon reaching the runout zone are also affected. These changes directly influence runout distances and have substantial implications for hazard and risk mapping. Particularly for snow avalanche modelling, entrainment leads to higher predicted flow heights and volumes of avalanches [15,32,33,34,35].

Accurate predictions are crucial for designing infrastructure, such as barriers or dams, as incorrect estimations may result in inadequate protection or increased costs. Therefore, precise consideration of entrainment is essential for determining runout distances and optimizing infrastructure design to mitigate hazards effectively.

3.3.1 Velocity model

This is a simple model that considers mass entrainment as function of the flow velocity. In contrast with another popular model, Iber-NNF considers entrainment when the flow velocity is greater than a threshold ( ).

|

|

(11) |

where is the entrainment rate, which commonly range from 5 to 40·10-5.

3.3.2 Height model

In this model, the entrainment depends on the load of the underlying snow cover as long as its height reaches a fixed minimum value ( ); otherwise, the entrainment will be considered inexistent [15]. This model also integrates an upper limit for the height based on the dry friction law to avoid the dry friction increasing limitless [36]:

|

|

(12) |

where is the entrainment rate, which commonly range from 1 to 8·10-3 s-1, and being the maximum avalanche flux height at which yielding at the basal surface occurs:

|

|

(13) |

3.3.3 Squared velocity model

This equation is similar to the velocity model although the entrainment rate is considered to vary with the squared velocity of the avalanche [15]:

|

|

(14) |

where is the entrainment rate, which commonly range from 4 to 32·10-6.

3.3.4 Bed shear stress model

Similar to how the sediment transport is computed, a new equation to calculate the entrainment as a function of the bed shear stress between the lower snow layer and the avalanche:

|

|

(15) |

where is the entrainment rate, which a range from 1.5 to 12·10-6 m·s-1·Pa-1 is proposed [16].

4 Results

As in the hydrodynamic module for water flows, Iber-NNF also integrates flow depths, velocities, elevation, etc. However, particular results can be activated through Data >> Problem data >> NonNewtonian fluid tab, such as extra topographical information (terrain slope) and impact forces [37,38]. This results essentially applies for dense snow avalanche modelling, but they are not limited to.

Particularly for impact forces, Iber-NNF calculates the dynamic pressure (Equation (16)), the peak dynamic pressure (Equation (17)) and its maximus as follows:

|

|

(16) | |

|

|

(17) |

where is the fluid density and is the fluid velocity.

References

[1] E. Bladé, L. Cea, G. Corestein, E. Escolano, J. Puertas, E. Vázquez-Cendón, J. Dolz, A. Coll, Iber: herramienta de simulación numérica del flujo en ríos, Rev. Int. Métodos Numéricos Para Cálculo y Diseño En Ing. 30 (2014) 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rimni.2012.07.004.

[2] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, P. Oller, G. Furdada, Numerical modelling of dense snow avalanches with a well-balanced scheme based on the 2D shallow water equations, J. Glaciol. (2023) 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2023.48.

[3] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, El rol de los términos de fricción y cohesión en la modelización bidimensional de fluidos no Newtonianos: avalanchas de nieve densa, Ing. Del Agua. 27 (2023) 295–310. https://doi.org/10.4995/ia.2023.20080.

[4] M. Sanz-Ramos, C.A. Andrade, P. Oller, G. Furdada, E. Bladé, E. Martínez-Gomariz, Reconstructing the Snow Avalanche of Coll de Pal 2018 (SE Pyrenees), GeoHazards. 2 (2021) 196–211. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards2030011.

[5] V. Ruiz-Villanueva, B. Mazzorana, E. Bladé, L. Bürkli, P. Iribarren-Anacona, L. Mao, F. Nakamura, D. Ravazzolo, D. Rickenmann, M. Sanz-Ramos, M. Stoffel, E. Wohl, Characterization of wood-laden flows in rivers, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms. 44 (2019) 1694–1709. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4603.

[6] M. Sanz-Ramos, J.J. Vales-Bravo, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, Reconstructing the spill propagation of the Aznalcóllar mine disaster, Mine Water Environ. 43 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10230-024-01000-5.

[7] M. Sanz-Ramos, E. Bladé, M. Sánchez-Juny, T. Dysarz, Extension of Iber for Simulating Non–Newtonian Shallow Flows: Mine-Tailings Spill Propagation Modelling, Water. 16 (2024) 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16142039.

[8] M. Sanz-Ramos, L. Cea, E. Bladé, D. López-Gómez, E. Sañudo, G. Corestein, G. García-Alén, J. Aragón-Hernández, Iber v3. Reference manual and user’s interface of the new implementations, CIMNE, 2022. https://doi.org/10.23967/iber.2022.01.

[9] Y. Ni, Z. Cao, Q. Liu, Mathematical modeling of shallow-water flows on steep slopes, J. Hydrol. Hydromechanics. 67 (2019) 252–259. https://doi.org/10.2478/johh-2019-0012.

[10] A. Maranzoni, M. Tomirotti, New formulation of the two-dimensional steep-slope shallow water equations. Part I: Theory and analysis, Adv. Water Resour. 166 (2022) 104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2022.104255.

[11] D. Zugliani, G. Rosatti, TRENT2D❄: An accurate numerical approach to the simulation of two-dimensional dense snow avalanches in global coordinate systems, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 190 (2021) 103343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2021.103343.

[12] V. Te Chow, Open-Channel Hydraulics, McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc. New York, USA, 1959.

[13] S.B. Savage, K. Hutter, The motion of a finite mass of granular material down a rough incline, J. Fluid Mech. 199 (1989) 177–215. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112089000340.

[14] M. Christen, J. Kowalski, P. Bartelt, RAMMS: Numerical simulation of dense snow avalanches in three-dimensional terrain, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 63 (2010) 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2010.04.005.

[15] M.E. Eglit, K.S. Demidov, Mathematical modeling of snow entrainment in avalanche motion, Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 43 (2005) 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2005.03.005.

[16] J. Castelló, Enhancement and application of numerical methods for snow avalanche modelling, Master thesis. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Barcelona, Spain, 2020.

[17] K. Msheik, Non-Newtonian Fluids: Modeling and Well-Posedness, Universite Grenoble Alpes, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2020. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03099969.

[18] P.Y. Julien, C.A. León, Mudfloods, mudflows and debrisflows, classification in rheology and structural design, in: Int. Work. Debris Flow Disaster 27 November–1 December 1999, 2000: pp. 1–15.

[19] T. Takahashi, Debris flow: mechanics and hazard mitigation, in: ROC-JAPAN Jt. Semin. Mul- Tiple Hazards Mitig., National Taiwan Univerisity, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC, 1985: pp. 1075–1092.

[20] A. Laenen, R.P. Hansen, Simulation of three lahars in the Mount St. Helens area, Washington, using a one-dimensional, unsteady-state streamflow model, 1988. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3133/wri884004.

[21] M. Syarifuddin, S. Oishi, R.I. Hapsari, D. Legono, Empirical model for remote monitoring of rain-triggered lahar at Mount Merapi, J. Japan Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. B1 (Hydraulic Eng. 74 (2018) I_1483-I_1488. https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejhe.74.I_1483.

[22] A.R. Darnell, J.C. Phillips, J. Barclay, R.A. Herd, A.A. Lovett, P.D. Cole, Developing a simplified geographical information system approach to dilute lahar modelling for rapid hazard assessment, Bull. Volcanol. 75 (2013) 713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-013-0713-6.

[23] E.C. Bingham, An investigation of the laws of plastic flow, Bull. Bur. Stand. 13 (1916) 309–353. https://doi.org/10.6028/bulletin.304.

[24] M. Pastor, B. Haddad, G. Sorbino, S. Cuomo, V. Drempetic, A depth‐integrated, coupled SPH model for flow‐like landslides and related phenomena, Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 33 (2009) 143–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/nag.705.

[25] H. Chen, C.F. Lee, Runout Analysis of Slurry Flows with Bingham Model, J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 128 (2002) 1032–1042. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2002)128:12(1032).

[26] D. Naef, D. Rickenmann, P. Rutschmann, B.W. McArdell, Comparison of flow resistance relations for debris flows using a one-dimensional finite element simulation model, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 6 (2006) 155–165. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-155-2006.

[27] A. Voellmy, Über die Zerstörungskraft von Lawinen, Schweizerische Bauzeitung. 73 (1955) 15. https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-61891.

[28] P. Bartelt, C.V. Valero, T. Feistl, M. Christen, Y. Bühler, O. Buser, Modelling cohesion in snow avalanche flow, J. Glaciol. 61 (2015) 837–850. https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126.

[29] G. Macedonio, M.T.T. Pareschi, Numerical simulation of some lahars from Mount St. Helens, J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 54 (1992) 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(92)90115-T.

[30] J.S. O’Brien, P.Y. Julien, Laboratory Analysis of Mudflow Properties, J. Hydraul. Eng. 114 (1988) 877–887. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1988)114:8(877).