(Created page with " =1. Introduction= One of the main problems with the thermoplastic consumption is the amount used in a day-to-day basis as well the way of disposal of the single-use plasti...") |

m (Marherna moved page Review 894336973829 to Carreiras et al 2025a) |

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 10:32, 6 July 2025

1. Introduction

One of the main problems with the thermoplastic consumption is the amount used in a day-to-day basis as well the way of disposal of the single-use plastic products (this includes for example plastic bottles, plastic bags and containers). Even though polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles represent a lower carbon footprint in terms of production and transportation, they still represent one of the biggest problems in landfill waste [1]. With the effects of the incorrect disposal of pet bottles in all ecosystems the search for alternative uses of these materials and the application of different types of PET recycling is of high priority [2]. This study focuses on testing a solution for one of the problems with PET waste of water and beverage bottles, in new engineering materials.

A lot of studies have been conducted to understand the environmental performance of some polymer alternatives to PET packaging [3]. Although the best solution is to close the loop in the usage of these materials and working on the expansion of the life cycle of PET, the recycling of this polymer can be chemical or mechanical, the main difference of the two types of recycling is the complexity of the process and the resulting material and amount of waste product [4]. Some studies have been successful in proving the possibly of maintaining the quality criteria and mechanical properties in the recycled material [5].

Knowing the possibility of recycling thermoplastic materials, and the fact that a large percentage of it still ends as landfill waste, brings the goal of transforming then into new materials [6]. That will be a new material with a lower carbon footprint.

Thermoplastic prepregs production and their consolidation processes are still a developing technology. One of the most efficient methods of processing is the pultrusion of constant cross section bars [7], being pultrusion of constant cross section bars one of the most efficient methods of processing. One of the improvements of this processing method is the application of pre-impregnated materials such as towpregs and pre-impregnated tapes that improve the consolidation quality of the resulting bars [8]. Pultruded thermoplastic composites have several advantages over thermosetting composites, ranging from lower risks for operators to improved quality. The higher impact toughness, the possibility of recycling and the reduction of the environmental impact are the most relevant advantages [9].

In this work the main objective is to create new combinations of materials were the polymers used are directly recycled and processed into their new form. The mechanical characterization of the materials is going to allow the comparison between the materials made from virgin material and understand the viability for this kind of recycling.

2. Experimental work

2.1. Selection of Raw materials

2.1.1. Fibres

Some aspects about the selection of fibres were studied, such as the linear density and sizing options available in the market, with the E-type glass fibres supplied by Owens Corning, reference 305E-TYPE 30 Direct Roving being selected. These fibres do not undergo any kind of sizing treatment and had a linear density of 2400 Tex. The carbon fibres used were supplied by SGL Group, with the reference C30 T050 TP1 having a sizing treatment for processing thermoplastic polymers, which is more adequate for the work here developed. The properties of this fibres are listed in Table 1.

| Glass Fibres | Carbon Fibres | ||

| Density ρ | g/cm3 | 2.56 | 1.80 |

| Linear density | g/m | 2.40 | 3.28 |

| Elasticity modulus E | GPa | 70 | 240 |

| Tensile strength | MPa | 1800 | 4000 |

| Filament Diameter | µm | 14 | 7 |

| Poisson ratio ν | - | 0.26 | 0.27 |

2.1.2. Thermoplastic matrix

The polyethylene terephthalate (PET) polymer used in the development of this work, as a comparative way to the new material under study, was supplied by Billion Industrial Co Lt., with reference 31W56/W and the relevant properties of the thermoplastic can be consulted in Table 2.

| PET | ||

| Density ρ | g/cm3 | 1.25 |

| Tensile strength τu | MPa | 40 |

| Elasticity modulus E | GPa | 2.0 |

| Melting temperature Tm | °C | 249 |

| Elongation at break ε | % | 20 |

| Heat Deflection Temp. HDT | °C | 115 |

| Poisson ratio ν | - | 0.43 |

This research used two types of recycled pet, one obtained in granules from DUY TAN PLASTIC RECYCLING CO. LTD and the second obtained by mechanically recycling water and soft drink bottles.

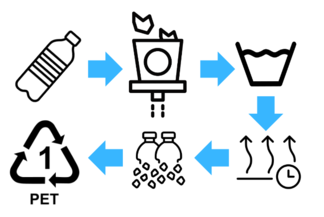

The first step to the method was the collecting of beverage bottles and the sorting and separation of every component that was not composed of PET. The selected material was then shredded into a desired size to facilitate its use. The next step was the disinfection and cleaning of the material, this process was done with a diluted solution of 1 part of acetone for 50 parts of water so it would not degrade the polymer. With the use of water, it was necessary to implement a drying process to guarantee the purity of the polymer granules. This process is represented in Figure 1.

There are still some gaps in this process, as the various types of PET collected sometimes have different additives, making it difficult to mix them. However, as the processes carried out bring the polymer to a temperature above its melting point, this problem has not been a limitation.

2.3. Pre-impregnated tapes

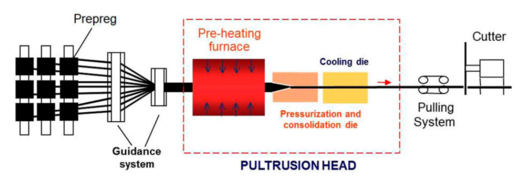

For this work pre-impregnated tapes were produced combining PET polymer with carbon fibres. The production of the tapes was carried out in the equipment schematically represented in Figure 2.

This pre-impregnated material is produced by passing continuous dry fibres through a polymer bath. Once the fibres are impregnated, they pass through a die where the geometry is defined. At the exit, the tape cools and it is possible to move on to other forming processes [10].

To produce the tapes for this study, it was used equipment that can heat the polymer up to 300ºC, with the pulling speed for these materials being set at 3 meters per minute. The geometry of the produced tapes was with 10 mm of width and 0.2 mm of thickness.

2.4. Consolidation of the material by pultrusion

The consolidation method by pultrusion is done according to the method and the steps described in Figure 3.

The processing parameters used in the processing of pultrusion profiles were the ones described in Table 3. It is also presented the number of roving’s used per condition. This number is calculated through the relation of linear density of the prepreg and the die dimension of the pultrusion system.

| Material | Pulling Speed

(m/min) |

Pre-heating

(°C) |

Consolidation

Die (°C) |

Cooling Die (°C) | Rovings |

| CF/PET | 0.2 | 135 | 275 | 25 | 10 |

| CF/rPET | 0.3 | 160 | 200 | 5 | |

| CF/rPET (bottles) | 0.3 | 160 | 200 | 5 | |

| GF/rPET (bottles) | 0.3 | 160 | 220 | 7 |

2.5. Mechanical testing

Mechanical testing was carried out in a Shimadzu AG-X equipment with a load cell of 100 kN for the tensile tests and a Shimadzu AG-I whit a load cell of 10 kN for the flexural tests. The flexural properties of the profiles obtained were determined under ISO 14125. This method was used to investigate the flexural behaviour of the profiles and determine the flexural strength and flexural modulus. The span was 80 mm, and the test speed was 2 mm/min.

The experimental results were compared with theoretical ones that can be predicted by using the ROM (Rule of Mixtures). Considering the void volume fraction to be equal to zero, the elastic modulus in the direction of fibres, 𝐸1, can be estimated by Equation 1.

|

|

(1) |

where 𝐸𝑓 and 𝐸𝑝 are the elastic modulus of fibres and polymer, respectively, and 𝑣𝑓 is the fibre volume fraction of composite.

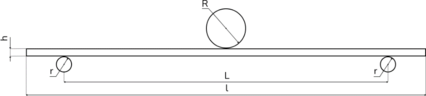

For these composites, a crosshead speed of 2 millimetres per minute is employed during the test and the stress interval for determining the material’s elastic modulus is derived from a strain ranging between 0.0005 and 0.0025. The placement of the specimen to proceed with the three-point test is shown at Figure 4.

Tensile test was carried out at a speed of 2 mm/min according to ISO 527, and distance between grippers was 150 mm. The tensile tests were done using an extensometer so the results of the Young´s Modulus could be more precise. The distance between the grippers of the extensometer was 50 mm.

3. Results

3.1. Production of the pre-impregnated tapes

The processing of the pre-impregnated tapes proved to be successful, both in the use of the raw material virgin and in the use of the recycled polymer. When using the polymer, it was essential to know its processing window, so it was essential to study the optimum flow temperature, and the degradation temperature studied.

The resulting tapes had the desired impregnation quality and a balanced fibre and polymer content, allowing them to be processed and the quantities of prepregs to be calculated to produce the pultrusion profiles.

3.2. Pultrusion of the pre-impregnated tapes

The pultrusion process showed some difficulties because of the amount of polymer present in the pre-impregnated tapes. For that reason, the processing temperatures had to be adjusted so the resulting material could show a good superficial quality.

There are some improvements that need to be made in future works on the quantity of material in relation with the processing speed.

After the production of the material the specimens were prepared, and the calcination tests were done. That way the theoretical properties could be calculated by the Rule of Mixtures and the values can be seen in Table 4.

| Composite | Theoretical Young´s Modulus

(GPa) |

Theoretical Strength (MPa) |

| CF/PET | 104.3 | 860 |

| CF/rPET | 126.5 | 1046 |

| CF/rPET(bottles) | 88.5 | 727 |

| GF/rPET(bottles) | 20.9 | 254 |

3.3. Mechanical testing results

The mechanical testing was made, and the results are the ones presented. The tensile tests results are presented in Table 5. Is also presented the Relative Elasticity modulus so it is easier to compare the properties of each material in relation with each fibre volume fraction.

| Composite | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Relative Young´s Modulus |

| CF/PET | 76.7 ± 6.7 | 499.4 ± 91.1 | 178.4 |

| CF/rPET | 50.3 ± 5.5 | > 468.7 ± 100.3 | 96.1 |

| CF/rPET (bottles) | 49.1 ± 5.4 | 441.1 ± 20.0 | 136.4 |

| GF/rPET (bottles) | 14.7 ± 2.4 | 129.5 ± 10.1 | 52.1 |

The flexural testing results are presented in Table 6 and as was done in the tensile characterization it was also calculated the relative flexural modulus.

| Composite | Flexural Modulus (GPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Relative Flexural Modulus |

| CF/PET | 31.5 ± 4.5 | 443.5 ± 59.3 | 137.9 |

| CF/rPET | 76.2 ± 9.9 | 468.7 ± 100.3 | 145.6 |

| CF/rPET (bottles) | 34.2 ± 4.3 | 384.6 ± 37.2 | 95 |

| GF/rPET (bottles) | 4.9 ± 1.4 | 25.4 ± 8.7 | 17.4 |

The results presented above show the significant difference between the composite material reinforced with carbon fibres when compared to the ones reinforced with glass fibres. The resulting material also showed better superficial quality and processing facility in the ones with carbon fibres then the ones with glass fibres.

Further work must be done to improve the process when using glass fibres as reinforcement. The flexural modulus of this material shows some difference from the ones predicted, this problem can be due to the poor consolidation of the specimen, being more evident when tested by applying a flexural stress.

On the other hand, the recycling process of the PET waste proved to be an excellent and easier method to reintroduce this material on the chain of materials and to improve the ecological footprint of the created material.

4. Conclusions

This study corroborated the theoretical predictions made when using recycled polymers. Despite using a more direct recycling process than that normally applied in industrial recycling, the material produced had properties close to those predicted by theory.

The production methods showed viability when working with recycled polymers, without a big change of parameters and processing capacity. The application of this direct polymer recycling process is therefore feasible in the production of composite materials. This study should be continued by applying the same methods, changing the polymers used and improving the process by using different continuous fibres.

In future work more thermal testing should be done in the polymers being recycled to understand how many temperatures cycles the polymer can stand without losing mechanical and chemical properties. This work should also be applied in more combinations of materials including more natural fibres and with different sizes of fibres to spread the applications of these materials obtained from more ecofriendly sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this work would like to thank M4S- Materials for sustainability research centre for all the support during the experimental component of this work.

5. Bibliography

[1] P. Benyathiar, P. Kumar, G. Carpenter, J. Brace, and D. K. Mishra, “Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Bottle‐to‐Bottle Recycling for the Beverage Industry: A Review,” Jun. 01, 2022, MDPI. doi: 10.3390/polym14122366.

[2] P. Bałdowska-Witos, I. Piasecka, J. Flizikowski, A. Tomporowski, A. Idzikowski, and M. Zawada, “Life cycle assessment of two alternative plastics for bottle production,” Materials, vol. 14, no. 16, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.3390/ma14164552.

[3] S. Papong et al., “Comparative assessment of the environmental profile of PLA and PET drinking water bottles from a life cycle perspective,” J Clean Prod, vol. 65, pp. 539–550, Feb. 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.030.

[4] T. Chilton, S. Burnley, and S. Nesaratnam, “A life cycle assessment of the closed-loop recycling and thermal recovery of post-consumer PET,” Resour Conserv Recycl, vol. 54, no. 12, pp. 1241–1249, 2010, doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.04.002.

[5] E. Pinter et al., “Circularity study on pet bottle-to-bottle recycling,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 13, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13137370.

[6] M. Asensio et al., “Processing of pre-impregnated thermoplastic towpreg reinforced by continuous glass fibre and recycled PET by pultrusion,” Compos B Eng, vol. 200, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108365.

[7] F. Tucci, F. Rubino, G. Pasquino, and P. Carlone, “Thermoplastic Pultrusion Process of Polypropylene/Glass Tapes,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 10, May 2023, doi: 10.3390/polym15102374.

[8] P. J. Novo, J. F. Silva, J. P. Nunes, F. W. J. Van Hattum, and A. T. Marques, “ECCM15-15 TH EUROPEAN CONFERENCE DEVELOPMENT OF A NEW PULTRUSION EQUIPMENT TO MANUFACTURE THERMOPLASTIC MATRIX COMPOSITE PROFILES.”

[9] K. Minchenkov, S. Gusev, A. Rogozheva, A. Tronin, M. Diatlova, and A. Safonov, “Pultrusion of thermoplastic composites with mechanical properties comparable to industrial thermoset profiles,” Composites Communications, vol. 44, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.coco.2023.101766.

[10] P. Esfandiari, J. F. Silva, P. J. Novo, J. P. Nunes, and A. T. Marques, “Production and processing of pre-impregnated thermoplastic tapes by pultrusion and compression moulding,” J Compos Mater, vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 1667–1676, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1177/00219983221083841.

Document information

Accepted on 06/07/25

Submitted on 14/04/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?