Jrodriguezc (talk | contribs) (Tag: Visual edit) |

m (Marherna moved page Review 155779800377 to Rodriguez et al 2025a) |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==2.1. Optimization strategy== | ==2.1. Optimization strategy== | ||

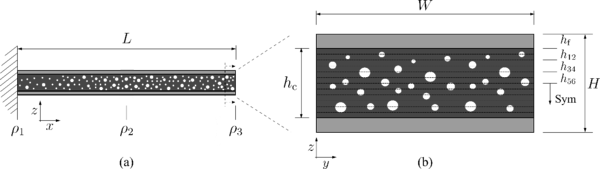

| − | In this study, rectangular sandwich plates with a length (''L'')'' ''of 180 mm, a width (''W'')'' ''of 90 mm and a height (''H'')'' ''of 6.8 mm were analyzed. The height consists of two aluminum face sheets (''h''<sub>f</sub>)of 1 mm and a 3D printed foamed PLA core (''h''<sub>c</sub>) of 4.8 mm, comprising 12 layers of 0.4 mm each. The boundary conditions included one embedded edge and three free edges, as shown in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]](a). Additionally, monolithic plates made entirely of foamed PLA were also analyzed, having the same size as the sandwich core. | + | In this study, rectangular sandwich plates with a length (''L'')'' ''of 180 mm, a width (''W'')'' ''of 90 mm and a height (''H'')'' ''of 6.8 mm were analyzed. The height consists of two aluminum face sheets (''h''<sub>f</sub>) of 1 mm and a 3D printed foamed PLA core (''h''<sub>c</sub>) of 4.8 mm, comprising 12 layers of 0.4 mm each. The boundary conditions included one embedded edge and three free edges, as shown in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]](a). Additionally, monolithic plates made entirely of foamed PLA were also analyzed, having the same size as the sandwich core. |

The design variables of the foamed PLA plates were reduced to three: the density in the embedded edge, the density in the middle of the length and the density at the free end of the plate. A linear distribution was applied in the longitudinal direction (the x axis direction in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]]) between each pair of density values, allowing the FG design in this direction. This criterion was applied to each layer pair (''h''<sub>12</sub>, ''h''<sub>34</sub> and ''h''<sub>56</sub>), ensuring symmetry of the core. Therefore, the longitudinal design strategy was defined for three independent layer pairs, as shown in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]](b). Thus, the total number of optimization variables was nine, corresponding to three densities per layer pair. | The design variables of the foamed PLA plates were reduced to three: the density in the embedded edge, the density in the middle of the length and the density at the free end of the plate. A linear distribution was applied in the longitudinal direction (the x axis direction in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]]) between each pair of density values, allowing the FG design in this direction. This criterion was applied to each layer pair (''h''<sub>12</sub>, ''h''<sub>34</sub> and ''h''<sub>56</sub>), ensuring symmetry of the core. Therefore, the longitudinal design strategy was defined for three independent layer pairs, as shown in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]](b). Thus, the total number of optimization variables was nine, corresponding to three densities per layer pair. | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | Optimization of the density distribution for each layer pair was | + | Optimization of the density distribution for each layer pair was performed by optimization studies using the commercial finite element method (FEM) package Abaqus and the genetic algorithm (GA) optimization method implemented on Matlab. The parametric FEM model configuration was implemented via a user-developed Python script for Abaqus. Reduced integration quadrilateral shell elements (S4R) were used in the model, with a general edge length of 5 mm. Each element of the FEM model was assigned a specific laminate. The material properties of each lamina is based on the centroid ''x'' position of the element, varying as a function of the density of the lamina. The GA Matlab code was configured with 20 generations and a population size of 60 per generation. The objective was to maximize the first two natural frequencies of a monolithic plate and a sandwich plate. The first natural frequency is a bending mode (<span id='cite-_Ref194565329'></span>[[#_Ref194565329|Figure 2]](a)) and the second one a torsional mode (<span id='cite-_Ref194565329'></span>[[#_Ref194565329|Figure 2]](b)). |

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

Table 1 presents the variable printing parameters, mechanical properties, and densities for both foamed and non-foamed parts. Tensile tests were performed to estimate the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio following the methodology described by Rodriguez et al. [13]. The fixed printing parameters were: 0.4 mm layer height and 0.8 mm raster width. | Table 1 presents the variable printing parameters, mechanical properties, and densities for both foamed and non-foamed parts. Tensile tests were performed to estimate the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio following the methodology described by Rodriguez et al. [13]. The fixed printing parameters were: 0.4 mm layer height and 0.8 mm raster width. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="_Ref193712693" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | Table 1. Printing parameters, density and elasticity properties of the reference cases. | ||

{| style="width: 66%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;" | {| style="width: 66%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

| Line 85: | Line 88: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 100: | Line 101: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

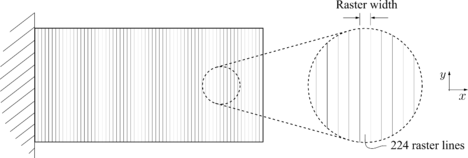

| − | Based on the optimization algorithm | + | Based on the results of the optimization algorithm, each raster line was assigned with a specific flow rate to adjust the density in that section. This process was repeated in all the 12 layers of the plates, always following the optimization results. The mechanical properties of the densities ranging between non-foamed and foamed values were estimated with a linear interpolation based on the characterization results at Table 1. |

==2.3. Vibration measurements== | ==2.3. Vibration measurements== | ||

| Line 121: | Line 122: | ||

The four reference cases are the monolithic non-foamed (MNF), monolithic foamed (MF), sandwich non-foamed (SNF), and sandwich foamed (SF) plates. The optimal cases are just two: the monolithic (MO) and the sandwich (SO) cases. The optimal density distribution obtained using the FEM-GA method to maximize the first two natural frequencies and the resulting natural frequencies are shown in <span id='cite-_Ref193787698'></span>[[#_Ref193787698|Table 2]]. The density distribution, represented as ''ρ''<sub>1</sub>, ''ρ''<sub>2</sub> and ''ρ''<sub>3</sub> in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]](a), corresponds to the flow rate value at each point: ''Fr''<sub>1</sub>, ''Fr''<sub>2</sub> and ''Fr''<sub>3</sub> in <span id='cite-_Ref193787698'></span>[[#_Ref193787698|Table 2]], which is proportional to the part density. | The four reference cases are the monolithic non-foamed (MNF), monolithic foamed (MF), sandwich non-foamed (SNF), and sandwich foamed (SF) plates. The optimal cases are just two: the monolithic (MO) and the sandwich (SO) cases. The optimal density distribution obtained using the FEM-GA method to maximize the first two natural frequencies and the resulting natural frequencies are shown in <span id='cite-_Ref193787698'></span>[[#_Ref193787698|Table 2]]. The density distribution, represented as ''ρ''<sub>1</sub>, ''ρ''<sub>2</sub> and ''ρ''<sub>3</sub> in <span id='cite-_Ref193719492'></span>[[#_Ref193719492|Figure 1]](a), corresponds to the flow rate value at each point: ''Fr''<sub>1</sub>, ''Fr''<sub>2</sub> and ''Fr''<sub>3</sub> in <span id='cite-_Ref193787698'></span>[[#_Ref193787698|Table 2]], which is proportional to the part density. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="_Ref193787698" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | Table 2. Results obtained with the FEM-GA method: reference and optimal configurations and the corresponding first two natural frequencies. | ||

{| style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;" | {| style="width: 100%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

| Line 168: | Line 172: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 192: | Line 194: | ||

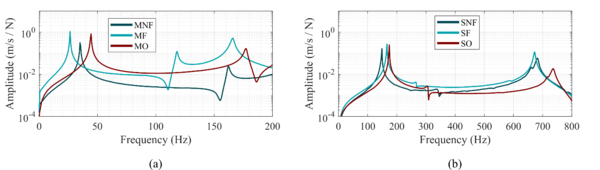

The two optimized plates were printed according to the optimization results and following the printing methodology defined in Section 2.2. The results of the optimized plates shown in Figure 3, along with those of the four reference plates, are presented in <span id='cite-_Ref193878534'></span>[[#_Ref193878534|Table 3]]. The experimental FRF curves for all cases are shown in <span id='cite-_Ref194586201'></span>[[#_Ref194586201|Figure 6]]. | The two optimized plates were printed according to the optimization results and following the printing methodology defined in Section 2.2. The results of the optimized plates shown in Figure 3, along with those of the four reference plates, are presented in <span id='cite-_Ref193878534'></span>[[#_Ref193878534|Table 3]]. The experimental FRF curves for all cases are shown in <span id='cite-_Ref194586201'></span>[[#_Ref194586201|Figure 6]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="_Ref193878534" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | Table 3. Comparison between the experimental and model results of the tested plates. | ||

{| style="width: 73%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;" | {| style="width: 73%;margin: 1em auto 0.1em auto;border-collapse: collapse;" | ||

| Line 253: | Line 258: | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:26, 2 July 2025

1. Introduction

Lightweight structural components are beneficial as they enhance energy efficiency. One effective approach is the use of sandwich composite structures, which provide a high stiffness-to-weight and a bending strength-to-weight ratio [1]. Further optimization is possible by replacing homogeneous cores with functionally graded (FG) structures, which allow for a gradual variation in material properties [2].

Manufacturing FG structures is challenging, making additive manufacturing (AM) an attractive alternative [3]. Fused deposition modeling (FDM) is a widely used AM technology that extrudes thermoplastic filament onto a build platform to produce complex geometries [4]. Among printable materials, polylactic acid (PLA) stands out due to its biodegradability, ease of processing, and environmental benefits [5].

A notable advancement in this area is foamed PLA, which incorporates a blowing agent activated by heat to create a stochastic porosity distribution. In 2019, ColorFabb introduced lightweight PLA (LW-PLA) [6], enabling the production of foamed PLA structures via FDM. Part densities ranging from 1240 kg/m³ to 400 kg/m³ can be achieved by adjusting the printing temperature and flow rate (FR), providing a high degree of control over the final properties of the printed parts [7-11].

Despite these advantages, to date only one study has focused on exploiting the benefits of FG structures using LW-PLA. Kanani et al. [12] employed LW-PLA to manufacture FG beams and analyzed their specific stiffness. However, their approach considered only a transverse FG distribution, varying the properties along the beam's thickness. They implemented this distribution by assigning different properties to each printed layer. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the vibratory behavior of FG cores made from 3D-printed foamed PLA. Furthermore, no established methodology exists for manufacturing FG structures with axial gradation, where the properties vary within the same printed layer.

The aim of the present study is to design and manufacture an optimized FG structure with both transverse and axial gradation to maximize the first two natural frequencies of a sandwich panel using a 3D-printed foamed PLA core and aluminum face sheets. FG structures were designed, produced, and tested, and their performance was compared to that of a conventional constant-density panel. This work provides a novel approach to enhancing the dynamic response of lightweight sandwich structural components.

2. Problem statement and methodology

This section details the optimization strategy of functionally graded LW-PLA cores using FEM and genetic algorithms, followed by FDM printing with controlled flow rates to achieve axial density gradation, and the methodology for vibration measurements in the plates.

2.1. Optimization strategy

In this study, rectangular sandwich plates with a length (L) of 180 mm, a width (W) of 90 mm and a height (H) of 6.8 mm were analyzed. The height consists of two aluminum face sheets (hf) of 1 mm and a 3D printed foamed PLA core (hc) of 4.8 mm, comprising 12 layers of 0.4 mm each. The boundary conditions included one embedded edge and three free edges, as shown in Figure 1(a). Additionally, monolithic plates made entirely of foamed PLA were also analyzed, having the same size as the sandwich core.

The design variables of the foamed PLA plates were reduced to three: the density in the embedded edge, the density in the middle of the length and the density at the free end of the plate. A linear distribution was applied in the longitudinal direction (the x axis direction in Figure 1) between each pair of density values, allowing the FG design in this direction. This criterion was applied to each layer pair (h12, h34 and h56), ensuring symmetry of the core. Therefore, the longitudinal design strategy was defined for three independent layer pairs, as shown in Figure 1(b). Thus, the total number of optimization variables was nine, corresponding to three densities per layer pair.

Figure 1. Case study of the sandwich plate: (a) longitudinal view and (b) cross section view. Only the height of the plate was kept proportional to the real dimensions; the length and width were shortened to save space and enhance comprehension.

Optimization of the density distribution for each layer pair was performed by optimization studies using the commercial finite element method (FEM) package Abaqus and the genetic algorithm (GA) optimization method implemented on Matlab. The parametric FEM model configuration was implemented via a user-developed Python script for Abaqus. Reduced integration quadrilateral shell elements (S4R) were used in the model, with a general edge length of 5 mm. Each element of the FEM model was assigned a specific laminate. The material properties of each lamina is based on the centroid x position of the element, varying as a function of the density of the lamina. The GA Matlab code was configured with 20 generations and a population size of 60 per generation. The objective was to maximize the first two natural frequencies of a monolithic plate and a sandwich plate. The first natural frequency is a bending mode (Figure 2(a)) and the second one a torsional mode (Figure 2(b)).

2.2. Printing methodology

The cores of the sandwich structure were manufactured using LW-PLA filament with a 1.75 mm diameter and printed using a Raise3D Pro3 HS desktop printer equipped with a 0.4 mm nozzle, and the ideaMaker 5.0.6 G-code slicer.

Table 1 presents the variable printing parameters, mechanical properties, and densities for both foamed and non-foamed parts. Tensile tests were performed to estimate the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio following the methodology described by Rodriguez et al. [13]. The fixed printing parameters were: 0.4 mm layer height and 0.8 mm raster width.

Table 1. Printing parameters, density and elasticity properties of the reference cases.

| Parameter | Unit | Foamed | Non-foamed |

| Flow rate | (%) | 45 | 110 |

| Hot-end temperature | (ᵒC) | 240 | 230 |

| Printing speed | (mm/s) | 60 | 80 |

| Density | (kg/m3) | 500 | 1190 |

| Elastic modulus | (MPa) | 488 | 2931 |

| Poisson’s ratio | (-) | 0.244 | 0.343 |

For printing the optimized plates with a functionally graded distribution, a 90° infill angle was used, aligning the raster lines perpendicular to the length of the beam (Figure 3). Each printed layer had a fixed raster width of 0.8 mm, so the 180 mm long plates contained a total of 224 raster lines. To achieve the target density in each raster line, the flow rate, hot-end temperature, and printing speed were adjusted using linear interpolation.

Figure 3. Infill angle of the functionally graded plates.

Based on the results of the optimization algorithm, each raster line was assigned with a specific flow rate to adjust the density in that section. This process was repeated in all the 12 layers of the plates, always following the optimization results. The mechanical properties of the densities ranging between non-foamed and foamed values were estimated with a linear interpolation based on the characterization results at Table 1.

2.3. Vibration measurements

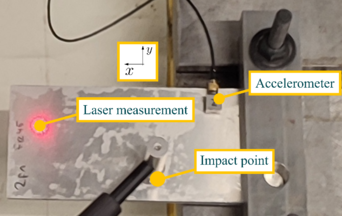

The most promising laminates were selected for manufacturing and testing. To facilitate clamping, the plates were made 30 mm longer and secured between two steel profiles bolted to a test platform (Figure 4). Their natural frequencies were determined from the characteristic frequency response functions (FRF). A medium-sized impact hammer (B&K 8206-003) was used for excitation, while a light triaxial accelerometer (B&K 4525 B) and laser vibrometer (Polytec) recorded the response.

To minimize the effect of the accelerometer’s mass, it was positioned near the mounting point, and the plate was excited with an impact hammer. Both points are shown in Figure 4. The plate was excited at the point shown in Figure 4. Data acquisition and processing were carried out using the PULSE Labshop spectrum analyzer. A 2 s time window was used, providing a frequency resolution of 0.5 Hz. With a sampling frequency of 8192 Hz, a frequency range of 3200 Hz was obtained.

3. Results and discussion

The following analysis compares the vibrational performance of homogeneous and functionally graded designs, examining both computational predictions and experimental measurements across monolithic and sandwich configurations.

3.1. Optimized sandwich core designs

The four reference cases are the monolithic non-foamed (MNF), monolithic foamed (MF), sandwich non-foamed (SNF), and sandwich foamed (SF) plates. The optimal cases are just two: the monolithic (MO) and the sandwich (SO) cases. The optimal density distribution obtained using the FEM-GA method to maximize the first two natural frequencies and the resulting natural frequencies are shown in Table 2. The density distribution, represented as ρ1, ρ2 and ρ3 in Figure 1(a), corresponds to the flow rate value at each point: Fr1, Fr2 and Fr3 in Table 2, which is proportional to the part density.

Table 2. Results obtained with the FEM-GA method: reference and optimal configurations and the corresponding first two natural frequencies.

| Design | hij (Fr1|Fr2|Fr3) | f1 (Hz) | f2 (Hz) | |

| MNF | Fr1 =Fr2 = Fr3 = 110 in all layers | 36.9 | 157.7 | |

| Monolithic | MF | Fr1 =Fr2 = Fr3 = 110 in all layers | 24.9 | 107.7 |

| MO | h12 (110|110|45); h34 (110|45|45); h56 (110|45|45) | 47.9 | 180.4 | |

| SNF | Fr1 =Fr2 = Fr3 = 110 in all layers | 177.1 | 675.8 | |

| Sandwich | SF | Fr1 =Fr2 = Fr3 = 110 in all layers | 201.4 | 653.4 |

| SO | h12 (110|45|45); h34 (110|45|45); h56 (110|45|45) | 206.6 | 729.5 |

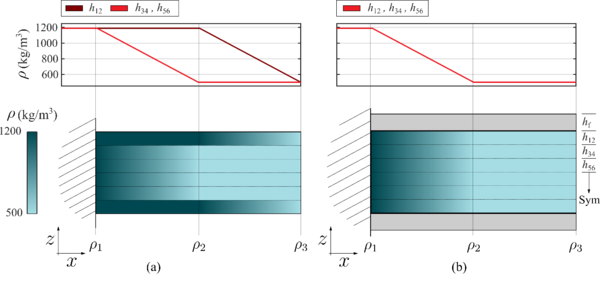

Figure 5(a) shows the optimized monolithic case, and Figure 5(b) the optimized sandwich case. The density distribution along the length for each layer pair is shown both schematically and with a chart.

Figure 5. Density distribution along the length of the plate in the (a) monolithic plate and (b) sandwich plate. The plate's length and height measurements were kept proportional.

Comparing the monolithic foamed case to the non-foamed one, both natural frequencies decrease. Even though it is lighter, the loss of stiffness exceeds the loss of mass, resulting in a 32.5% and 31.7% reduction in the first and second natural frequencies, respectively. In sandwich structures, where most of the bending stiffness is supported by the face sheets, the mass reduction in the core increases the first natural frequency. However, the second natural frequency is torsional, meaning core stiffness plays a larger role, preventing an increase.

For the optimized monolithic FG design, the optimization proposes a configuration where the outer layers are the stiffest, while the inner layers are lighter, maintaining the highest density at the clamp to ensure maximum rigidity in the clamped region By adopting a configuration similar to a sandwich structure, this configuration preserves most of the plate's structural rigidity while substantially reducing mass, resulting in a 29.8% and 14.4% increase in the first and second natural frequencies, respectively.

In the sandwich case, the outer layer stiffness is provided by the aluminum face sheets, so the entire core was designed to minimize weight. As in the monolithic case, the density at the clamped region is the highest to ensure maximum rigidity in this critical area.

3.2. Experimental validation

The two optimized plates were printed according to the optimization results and following the printing methodology defined in Section 2.2. The results of the optimized plates shown in Figure 3, along with those of the four reference plates, are presented in Table 3. The experimental FRF curves for all cases are shown in Figure 6.

Table 3. Comparison between the experimental and model results of the tested plates.

| f1 (Hz) | f2 (Hz) | ||||

| Design | Test | Model | Test | Model | |

| MNF | 35 | 36.9 | 162 | 157.7 | |

| Monolithic | MF | 26.5 | 24.9 | 118 | 107.7 |

| MO | 44.5 | 47.9 | 177.5 | 180.4 | |

| SNF | 149 | 177.1 | 682 | 675.8 | |

| Sandwich | SF | 167 | 201.4 | 672.5 | 653.4 |

| SO | 175 | 206.6 | 736 | 729.5 |

Figure 6. Experimental FRF curves for (a) monolithic plates and (b) sandwich plates.

Experimental results confirm the behavior predicted by the FEM model. The optimized monolithic panels increased the first and second natural frequencies by 27.1% and 10%, respectively. For sandwich structures, the achieved increase was 17.1% and 7.9%, respectively.

The model predicted higher natural frequencies than those measured for the first mode, overestimating values by approximately 8% in monolithic cases and 16% in sandwich cases. Maintaining good raster adhesion across all 224 raster lines along the plate length is challenging, especially when using the FG strategy. Local adhesion defects might reduce the plate’s stiffness in the longitudinal direction, resulting in lower natural frequencies than those predicted.

The prediction for the second natural frequency was more accurate, with errors below 3% in all cases. However, in both natural frequencies, the optimized plates successfully increased natural frequencies compared to their reference counterparts while reducing weight. Note that the optimized printed plates weighed 30.9% and 37.9% less than the homogeneous high-density reference counterparts, with the former being the monolithic plate and the latter the sandwich core.

4. Concluding remarks

This study has demonstrated that FDM printing with foamable filament is a viable method for manufacturing FG structures that enhance the dynamic response of both monolithic and sandwich structural plates. Compared to a homogeneous core, the first natural frequency increased by more than 27% in monolithic plates and 16% in sandwich plates. The second natural frequency rose by approximately 8% in both optimized plates.

These results encourage further research on 3D printing of FG components using foamable filaments. Other dynamic properties, such as damping, could also be effectively optimized while reducing component weight.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Basque government under MATFUN KK-2021/00066, and by the Provincial Council of Gipuzkoa under NUCAVA.

6. Bibliography

[1] P. R. Oliveira, M. May, T. H. Panzera, and S. Hiermaier, “Bio-based/green sandwich structures: A review,” Aug. 01, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. doi: 10.1016/j.tws.2022.109426.

[2] D. Chen, K. Gao, J. Yang, and L. Zhang, “Functionally graded porous structures: Analyses, performances, and applications – A Review,” Thin-Walled Structures, vol. 191, p. 111046, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1016/J.TWS.2023.111046.

[3] S. Yadav, S. Liu, R. K. Singh, A. K. Sharma, and P. Rawat, “A state-of-art review on functionally graded materials (FGMs) manufactured by 3D printing techniques: Advantages, existing challenges, and future scope,” Dec. 12, 2024, Elsevier Ltd. doi: 10.1016/j.jmapro.2024.10.026.

[4] X. Wang, M. Jiang, Z. Zhou, J. Gou, and D. Hui, “3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective,” Feb. 01, 2017, Elsevier Ltd. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.11.034.

[5] S. Farah, D. G. Anderson, and R. Langer, “Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications — A comprehensive review,” Dec. 15, 2016, Elsevier B.V. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.06.012.

[6] ColorFabb, “Technical datasheet LW-PLA.” Accessed: Sep. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://colorfabb.com/media/datasheets/tds/colorfabb/TDS_E_ColorFabb_LW-PLA.pdf

[7] I. Dinakaran, C. Sakib-Uz-Zaman, A. Rahman, and M. A. H. Khondoker, “Controlling degree of foaming in extrusion 3D printing of porous polylactic acid,” Rapid Prototyp J, vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 1958–1968, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1108/RPJ-02-2023-0044.

[8] A. R. Damanpack, A. Sousa, and M. Bodaghi, “Porous plas with controllable density by fdm 3d printing and chemical foaming agent,” Micromachines (Basel), vol. 12, no. 8, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.3390/mi12080866.

[9] F. de Freitas and H. Pegado, “Impact of nozzle temperature on dimensional and mechanical characteristics of low-density PLA,” International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, vol. 126, no. 3–4, pp. 1629–1638, May 2023, doi: 10.1007/s00170-023-11236-0.

[10] A. Alduais and S. Özerinç, “Tunable mechanical properties of thermoplastic foams produced by additive manufacturing,” Express Polym Lett, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 317–333, Mar. 2023, doi: 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2023.23.

[11] A. Yousefi Kanani, A. E. W. Rennie, and S. Z. Bin Abd Rahim, “Additively manufactured foamed polylactic acid for lightweight structures,” Rapid Prototyp J, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 50–66, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1108/RPJ-03-2022-0100.

[12] A. Yousefi Kanani and A. Kennedy, “Experimental and numerical analysis of additively manufactured foamed sandwich beams,” Compos Struct, vol. 312, May 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.116866.

[13] Jon Rodriguez, Mikel Iragi, Ondiz Zarraga, Jaione Iriondo, Aitziber Aizpuru, and Alex McCloskey, “3D printing of foamed PLA with variable mechanical properties for optimised lightweight sandwich cores,” in 21st European Conference on Composite Materials (ECCM21) Proceedings, Vol. 3, European Society for Composite Materials (ESCM), 2024, pp. 1584–1590.

Document information

Accepted on 02/07/25

Submitted on 11/04/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?