Asuncantera (talk | contribs) (Initial prof, the images don´t appeare) (Tag: Visual edit) |

Asuncantera (talk | contribs) (Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

=1. Introduction= | =1. Introduction= | ||

| − | In general, there are six types of natural fibres, depending on whether they are obtained from the stalk, leaves, seeds, straw or grass. The long plant fibres (flax, hemp, jute, kenaf and ramie) are the most effective of these, exhibiting excellent specific mechanical properties [1]. | + | In general, there are six types of natural fibres, depending on whether they are obtained from the stalk, leaves, seeds, straw, or grass. The long plant fibres (flax, hemp, jute, kenaf, and ramie) are the most effective of these, exhibiting excellent specific mechanical properties [1]. |

However, it is important to note that biofibres tend to adhere poorly to hydrophobic matrices. This means that either the fibres or the matrix need to be modified to enhance the mechanical properties of the composite [2]. An increasing number of scientific publications are focusing on treated natural fibres and modified matrices. Consequently, the wide variety of natural fibres (with and without treatments) and matrices (with and without additives) makes it difficult to estimate and compare their stiffness and strength, and to select the most suitable option for a specific application. | However, it is important to note that biofibres tend to adhere poorly to hydrophobic matrices. This means that either the fibres or the matrix need to be modified to enhance the mechanical properties of the composite [2]. An increasing number of scientific publications are focusing on treated natural fibres and modified matrices. Consequently, the wide variety of natural fibres (with and without treatments) and matrices (with and without additives) makes it difficult to estimate and compare their stiffness and strength, and to select the most suitable option for a specific application. | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

The invariants-based design theory used can be applied not only to man-made composites, but also to any orthotropic laminate [3]. Mathematically, the stiffness tensor trace, Tr, is a property of each material, regardless of the lay-up of the composite [4]. In this sense, the trace can be used to scale the stiffness of different materials and to rank them in a hierarchy. | The invariants-based design theory used can be applied not only to man-made composites, but also to any orthotropic laminate [3]. Mathematically, the stiffness tensor trace, Tr, is a property of each material, regardless of the lay-up of the composite [4]. In this sense, the trace can be used to scale the stiffness of different materials and to rank them in a hierarchy. | ||

| − | This study first establishes an empirical relationship between the trace Tr and the longitudinal, transversal and shear modulus of elasticity for flax [5], hemp [6] ,and kenaf [7]. This means that knowing one parameter such as the trace, enables the others to be determined. This is achieved for tension in the present study. Secondly, parameters related to the area of the Omni are proposed. These parameters are then used to calculate the empirical relationship in 14 configurations of Double-Double[8] with longitudinal tensile strength (X<sub>T</sub>) and longitudinal compressive strength (X<sub>C</sub>). Thirdly, it provides a means of comparing the NFRCs with each other and with other composites. | + | This study first establishes an empirical relationship between the trace Tr and the longitudinal, transversal, and shear modulus of elasticity for flax [5], hemp [6] ,and kenaf [7]. This means that knowing one parameter such as the trace, enables the others to be determined. This is achieved for tension in the present study. Secondly, parameters related to the area of the Omni are proposed. These parameters are then used to calculate the empirical relationship in 14 configurations of Double-Double[8] with longitudinal tensile strength (X<sub>T</sub>) and longitudinal compressive strength (X<sub>C</sub>). Thirdly, it provides a means of comparing the NFRCs with each other and with other composites. |

=2. Materials and Methods= | =2. Materials and Methods= | ||

Revision as of 13:18, 21 May 2025

1. Introduction

In general, there are six types of natural fibres, depending on whether they are obtained from the stalk, leaves, seeds, straw, or grass. The long plant fibres (flax, hemp, jute, kenaf, and ramie) are the most effective of these, exhibiting excellent specific mechanical properties [1].

However, it is important to note that biofibres tend to adhere poorly to hydrophobic matrices. This means that either the fibres or the matrix need to be modified to enhance the mechanical properties of the composite [2]. An increasing number of scientific publications are focusing on treated natural fibres and modified matrices. Consequently, the wide variety of natural fibres (with and without treatments) and matrices (with and without additives) makes it difficult to estimate and compare their stiffness and strength, and to select the most suitable option for a specific application.

This study examines how these modifications are reflected in significant parameters that are common to the NFRCs (Natural Fibers Reinforced Composites) under investigation. This enables direct comparisons to be made between different types of fibres and laminates. The aim is to avoid the excessive complexity of using multiple parameters, which often produce highly scattered experimental results. To reduce this scatter, the elementary parameters are normalised using the trace and radius of a circle with an area equivalent to that of the failure envelope in stress space.

The invariants-based design theory used can be applied not only to man-made composites, but also to any orthotropic laminate [3]. Mathematically, the stiffness tensor trace, Tr, is a property of each material, regardless of the lay-up of the composite [4]. In this sense, the trace can be used to scale the stiffness of different materials and to rank them in a hierarchy.

This study first establishes an empirical relationship between the trace Tr and the longitudinal, transversal, and shear modulus of elasticity for flax [5], hemp [6] ,and kenaf [7]. This means that knowing one parameter such as the trace, enables the others to be determined. This is achieved for tension in the present study. Secondly, parameters related to the area of the Omni are proposed. These parameters are then used to calculate the empirical relationship in 14 configurations of Double-Double[8] with longitudinal tensile strength (XT) and longitudinal compressive strength (XC). Thirdly, it provides a means of comparing the NFRCs with each other and with other composites.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental data with relevant information on the elastic properties of unidirectional flax, hemp, and kenaf composites are obtained from scientific publications, dissertations, and published reviews [5-7]. They are classified according to the type of load, and the presence or absence of chemical modification. Logically, each composite is manufactured with a different percentage by volume. Applying the normalization methodology used in the Composite Materials Handbook [9,10], a normalizing volume fraction of 0.4% was chosen, assuming that stiffness properties have a linear relationship with volume fraction as a first approximation. Then, a metadata analysis of unidirectional NFRC was carried out. The following scheme, Figure 1, illustrates the working process applied to the experimental data.

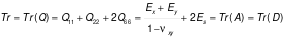

The trace Tr [4] is the in-plane stiffness matrix, also Known as the Tsa's modulus or trace Tr, it is calculated from the plane stress components ![]() or the elastic properties (see Eq. 1).

or the elastic properties (see Eq. 1).

|

(1) |

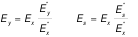

Some exact values of the trace-normalised values will be calculated in accordance with equation 2 for the longitudinal, transversal and shear moduli [5-7].

|

(2) |

The values of the longitudinal, transversal, shear modulus of NF fiber were back-calculated using micromechanical approaches: wh,re the traditional rule of mixtures was improved intrby oducing the void volume fraction [11]. The semiempirical Halpin-Tsai equation is also used, considering the shape factor for plant fibers coposites with an elliptical cross-section with a/b= 1.42 to 2.55 [10]. The estimation of the effective moduli in the transversal and shear direction is obtained using Eq.(3)

|

(3) |

If the longitudinal tensile modulus (𝐸x) is plotted against the trace, a unique property of NFRPs are revealed: the trace normalized modulus ![]() with a very low Coefficient Of Variation (CoV). Similarly, this can be done with transversal and shear moduli.

with a very low Coefficient Of Variation (CoV). Similarly, this can be done with transversal and shear moduli.

The concept of Master Ply [3] is be used to simplify the design by representing the average values of all laminates in a family and obtaining normalised values. These values are used to represent a specific family of composites, taking into account a scaled material factor (stiffness and strength). Tsai and Melo [3] proposed the Omni Strain Failure Envelopes. The area of the failure envelopes in both stress and strain space is an important parameter for representing the strength of a material/laminate and generating master envelopes. In strain space, the failure envelope of a ply is invariant, independent of the presence of adjacent plies. In a generic multidirectional laminate, the inner envelope covers any lay-up configuration and is controlled by the [0] and [90] plies. Therefore, it is a material propety . To avoid scatter, these radius values can be normalized

by dividing by the Master Ply radius, RMasterPly which is the average radius of all the Unidirectional composites considered in this study. The major diameter of the stress space envelopes D can also be used as a parameter for the strength of the composites.

3. Results

To compare the stiffness of different types of composites, natural and non-natural the same dimensionless parameter can be used. All values show a linear relationship on a double logarithmic scale, with different slope sand CoV ,as it is shown in Figure2 . The ratio of the tensile normalized modulus of different lay-ups with [0/90] as the baseline is shown in Figure 2b, for the synthetic and natural fibers listed in Table1

a)

b)

Figure 2 a) The linear relationship between the longitudinal tensile modulus and its trace for natural and non-natural composites. b) Comparison of trace-normalized longitudinal modulus and their ratio respect to [0/90].

The Table 1 shows the values and coefficients of variation for the trace normalised modulus and the ratio of material properties of different composites. The CoV of the Nis are reasonable, considering the typical scatter of mechanical properties in NFs. It is noteworthy that the relative mechanical behaviour of the unidirectional NFRP with respect to the cross-ply is very similar to that of human-made composites, and the ratio ![]() is better than synthetic composites.

is better than synthetic composites.

Table 1 Trace-normalized tensile mechanical properties of common composite families, the CoV is given in parentheses.

For strength comparison, another parameter is proposed the normalized radius R* . To obtain it, four important steps were taken:

- First, superposition in strain space is used to define an envelope that is independent of the lay-up.

- Second, convert it into the stress space. The Omni Stress Envelope The Last Ply Failure (LPF) of Omni Envelope depends on the tensile and compressive strength ,XT and XC. Assuming that, after matrix Degradation in the LPF hdoes not influencethe transverse and shear properties. The shape of the failure envelopes depends on the configuration of the laminate, as it is shown in Figure 3a

- Third, to simplify the structures, the largest diameter D and the area was identified for each case. To unify the area of all the envelopes, a radius R of a circle of equivalent area was calculated, as it is shown in Figure 3b. The average radius is related to the radius of the Master Ply and the absolute values and normalized to the radius of the Master Ply radius, giving R*.

- Finally, the experimental relationship between the R* value and the average tensile and compressive strengths was found for all the NFRPs investigated, as it is shown in Figure 3c

- 1)

- 2)

- 3) 336px

Figure3 a) The Omni Stress Envelope of different Flax composites with the same lay-up, b) equivalent circle of radius R with the same area than the stress envelope, c) linear relation between the trace normalize parameters of Radius and major Diameter

4. Discussion

Using the trace as a single parameter to quantify the stiffness of a composite greatly simplifies the collection and use of NFRC mechanical data. With only one value, it is possible to rank the stiffness of a specific fibre and compare it with that of other composites. Knowing the trace makes it easy to calculate and normalise the other stiffness parameters in the transverse and shear directions. Obtaining experimental values in the transverse and shear directions is challenging and time-consuming. However, the methodology explained in this article makes it possible to easily obtain values that can be used in the predesign stage.

The radius of a circle with an equivalent area to the stress envelopes is a useful parameter for quantifying and comparing the strength of composite materials. Using the radius of the master ply to normalise the radius R, a linear relationship was found between R* and the average tensile and compressive strength. R* can be used to rank composite materials by strength.

5. Conclussion

Remarkably, the relationship between the longitudinal modulus Ex and the trace Tr is linear for all analysed composites, whether natural or non-natural. This provides a material parameter ![]() associated with each fibre. These experimentally based parameters have a low Coefficient of Variation.

associated with each fibre. These experimentally based parameters have a low Coefficient of Variation.

Having a single parameter, R, that is directly connected with the area of the Omni Stress Envelope is also a great advantage in terms of strength.

Acknowledgments The author is particularly grateful to Professor Steve Tsai for the intensive exchange, many valuable discussions on this subject and beyond, and also for providing access to the Stanford’s Composites Workshop in various years.The author would like to thank Arushi Surve, Bruno Pech of the Alliance for European Flax-Linen & Hemp, and their reviewers for their time and useful comments. The author gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) in the Research Group GIU21/015 “Mechanics of Materials”

6. Biography

1. Sankar PS, Singh SB. Mechanical Characterization of Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites. In: Singh SB, Gopalarathnam M, Kodur VKR, Matsagar VA, editors. Fiber Reinforced Polymeric Materials and Sustainable Structures. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore978-981-19-8979-7, 2023. p. 65-80.

2. Koohestani B, Darban AK, Mokhtari P, Yilmaz E, Darezereshki E. Comparison of different natural fiber treatments: a literature review. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology ;2019;16(1):629-642;https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-018-1890-9.

3. Tsai SW, Melo JDD. An invariant-based theory of composites. Composites Sci Technol ;2014;100:237-243;https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2014.06.017.

4. Tsai SW, Pagano NJ. Invariant properties of composite materials. Composite materials workshop, St. Louis, Missouri, Technomic Publishing Company 1968:233-53.

5. Cantera MA. New Insights into the Stiffness and Strength of Flax Composites from Tsai’s Modulus and the Area of the Failure Envelope. Fibers and Polymers;2024;https://doi.org/10.1007/s12221-024-00779-y.

6. Cantera MA. Estimation of longitudinal and transverse stiffness of hemp fibers and their composites using experimental material parameters and invariants. Polymer Composites ;2025;n/a;10.1002/pc.29810.

7. Cantera MA, Stiffness prediction of kenaf composites and fibres. In: ICNF2025 – the 7th International Conference on Natural Fibers. 16-18 June, 2025.

8. Tsai SW. Double-Double: A New Perspective in Manufacture and Design of Composites. : Composites Design Group, Department of Aeronautics & Astronautics, Stanford University, 2022.

9. UsDeptOfDefense. Composite Materials Handbook-MIL 17, Volume I: Guidelines for Characterization of Structural Materials. : Routledge, 2019.

10. The Composite Materials Handbook (MIL Handbook 17). Volume 2: Materials Properties. United States: Lancaster, PA (United States); Technomic Publishing Company, Inc, 1999.

11. Madsen B, Lilholt H. Physical and mechanical properties of unidirectional plant fibre composites—an evaluation of the influence of porosity. Composites Sci Technol ;2003;63(9):1265-1272;https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00097-6.

Document information

Published on 21/10/25

Accepted on 17/08/25

Submitted on 24/07/25

Volume 09 - Comunicaciones MatComp25 (2025), Issue Núm. 2 - Reciclaje y Sostenibilidad, 2025

DOI: 10.23967/r.matcomp.2025.09.13

Licence: Other