| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Kirigami structures offer advantages such as relatively simple manufacturability, low-energy initial deployment, high load-bearing capacity, and deformation energy absorption once deployed and formed into a three-dimensional structure. These properties make them attractive for applications in aerospace, biomedical devices, and soft robotics [11]–[15], where initial compactness, lightweight, and portability are highly desired features. In this regard, a key advantage of kirigami-based structures is their ability to be transported in a compact, flat state and then deployed into their functional three-dimensional configurations. This characteristic reduces storage and transportation costs while enabling adaptability in constrained environments. However, one of the major challenges in kirigami-based structures is the formation of plastic hinges during deployment. Repeated folding and unfolding in traditional kirigami can lead to material fatigue and plasticity-related damage, ultimately reducing the structure's reliability and lifespan. This issue becomes even more critical when implementing kirigami with fiber-reinforced composites, where material anisotropy and layer adhesion further complicate mechanical performance. While kirigami-based structures have been explored in metallic and polymeric materials, their implementation in fiber-reinforced 3D-printed composites remains largely unexplored [12], [16], [17]. Integrating fiber reinforcement into kirigami structures presents opportunities for improving mechanical performance by optimizing load distribution, reducing stress concentrations at folds, and enhancing failure resistance. | Kirigami structures offer advantages such as relatively simple manufacturability, low-energy initial deployment, high load-bearing capacity, and deformation energy absorption once deployed and formed into a three-dimensional structure. These properties make them attractive for applications in aerospace, biomedical devices, and soft robotics [11]–[15], where initial compactness, lightweight, and portability are highly desired features. In this regard, a key advantage of kirigami-based structures is their ability to be transported in a compact, flat state and then deployed into their functional three-dimensional configurations. This characteristic reduces storage and transportation costs while enabling adaptability in constrained environments. However, one of the major challenges in kirigami-based structures is the formation of plastic hinges during deployment. Repeated folding and unfolding in traditional kirigami can lead to material fatigue and plasticity-related damage, ultimately reducing the structure's reliability and lifespan. This issue becomes even more critical when implementing kirigami with fiber-reinforced composites, where material anisotropy and layer adhesion further complicate mechanical performance. While kirigami-based structures have been explored in metallic and polymeric materials, their implementation in fiber-reinforced 3D-printed composites remains largely unexplored [12], [16], [17]. Integrating fiber reinforcement into kirigami structures presents opportunities for improving mechanical performance by optimizing load distribution, reducing stress concentrations at folds, and enhancing failure resistance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | [[File:Draft_Dolz_104064930_1212_Figure_1.png|center|800px]]</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="_Ref195524714" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 1: 3D Printed kirigami picture (a) flat undeployed state; (b) (c) deployed state and position of plastic hinges.''</span></div> | ||

| − | |||

One of the most critical aspects of 3D-printed kirigami composite structures is the design of their joints and interlayer bonding, which dictate their deployability and mechanical robustness. Traditional kirigami designs rely on thin plastic hinges or stress concentration regions for flexibility. Still, these features can be susceptible to damage when subjected to cyclic or high-stress loading conditions [11], [18], [19]. Strategies such as modifying printing parameters, incorporating mechanical interlocks, and utilizing post-processing treatments have been proposed to enhance joint performance [20], [21]. Still, their effectiveness in kirigami-inspired structures has not been extensively studied. The need for novel yet simple and reliable joint designs that balance flexibility and strength remains a major challenge in the field. <span id='cite-_Ref195537577'></span>[[#_Ref195537577|Figure 1]] presents a preliminary 3D-printed kirigami design adopted from the literature [11], highlighting the flat initial state, the deployed state, and the position of the plastic joints under consideration in this study. | One of the most critical aspects of 3D-printed kirigami composite structures is the design of their joints and interlayer bonding, which dictate their deployability and mechanical robustness. Traditional kirigami designs rely on thin plastic hinges or stress concentration regions for flexibility. Still, these features can be susceptible to damage when subjected to cyclic or high-stress loading conditions [11], [18], [19]. Strategies such as modifying printing parameters, incorporating mechanical interlocks, and utilizing post-processing treatments have been proposed to enhance joint performance [20], [21]. Still, their effectiveness in kirigami-inspired structures has not been extensively studied. The need for novel yet simple and reliable joint designs that balance flexibility and strength remains a major challenge in the field. <span id='cite-_Ref195537577'></span>[[#_Ref195537577|Figure 1]] presents a preliminary 3D-printed kirigami design adopted from the literature [11], highlighting the flat initial state, the deployed state, and the position of the plastic joints under consideration in this study. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 29: | ||

The test specimens were manufactured using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) with a consumer-grade 3D printer (Creality, Ender E-S1-Pro), which allows for detailed layer-by-layer printing of polymer materials. A polylactic acid (PLA), 1.75 mm in diameter filament, was utilized to manufacture specimens as part of a preliminary evaluation of notch designs. To ensure the material's optimal behavior during printing, it was stored in a dry environment to prevent moisture absorption, which could otherwise lead to defects in the printed parts and inconsistencies in mechanical properties. The printing process was conducted with a layer height of 0.2 mm and a printing speed of 50 mm/sec, which are typical values for acceptable print quality at a reasonable printing time. The layer height was chosen to ensure that the details of the notch geometries were represented while maintaining an efficient production time. A 100% infill density was also selected to maximize the samples' internal homogeneity and mechanical resistance. Five specimens were printed for each configuration to ensure repeatability and account for any variability in the printing process. | The test specimens were manufactured using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) with a consumer-grade 3D printer (Creality, Ender E-S1-Pro), which allows for detailed layer-by-layer printing of polymer materials. A polylactic acid (PLA), 1.75 mm in diameter filament, was utilized to manufacture specimens as part of a preliminary evaluation of notch designs. To ensure the material's optimal behavior during printing, it was stored in a dry environment to prevent moisture absorption, which could otherwise lead to defects in the printed parts and inconsistencies in mechanical properties. The printing process was conducted with a layer height of 0.2 mm and a printing speed of 50 mm/sec, which are typical values for acceptable print quality at a reasonable printing time. The layer height was chosen to ensure that the details of the notch geometries were represented while maintaining an efficient production time. A 100% infill density was also selected to maximize the samples' internal homogeneity and mechanical resistance. Five specimens were printed for each configuration to ensure repeatability and account for any variability in the printing process. | ||

| + | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | [[File:Draft_Dolz_104064930_4821_probeta_medidas_shapes.png|center|800px]]</div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="_Ref195524714" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 2: Specimen dimensions and notch shapes and dimensions.''</span></div> | ||

| − | |||

'''2.2 Mechanical Testing Procedures''' | '''2.2 Mechanical Testing Procedures''' | ||

| Line 36: | Line 45: | ||

* Four-Point Bending Test: This test is based on the ASTM D6272-17 standard, in which the specimens are placed onto two outer supports while two inner loading points apply force at a constant displacement rate (1 mm/min) (<span id='cite-_Ref195092263'></span>[[#_Ref195092263|Figure 3]] (c)). The distance between lower supports was 100 mm, and the upper loading points were positioned at 25 mm from each lower support. This configuration ensured a uniform bending moment in the central section of the specimen, minimizing shear effects and allowing for a more accurate evaluation of flexural properties. | * Four-Point Bending Test: This test is based on the ASTM D6272-17 standard, in which the specimens are placed onto two outer supports while two inner loading points apply force at a constant displacement rate (1 mm/min) (<span id='cite-_Ref195092263'></span>[[#_Ref195092263|Figure 3]] (c)). The distance between lower supports was 100 mm, and the upper loading points were positioned at 25 mm from each lower support. This configuration ensured a uniform bending moment in the central section of the specimen, minimizing shear effects and allowing for a more accurate evaluation of flexural properties. | ||

| + | |||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-picture-Grupo 18.svg|center|1000px]]</div> | |

| − | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-picture-Grupo 18.svg|center| | + | |

| − | </div> | + | |

<div id="_Ref195092263" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="_Ref195092263" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 3: Test setups. a) Torsion test; b) Cantilever bending test; c) Four-point bending test.''</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 3: Test setups. a) Torsion test; b) Cantilever bending test; c) Four-point bending test.''</span></div> | ||

| + | |||

=3. Results and discussion= | =3. Results and discussion= | ||

| Line 52: | Line 61: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-image6.png| | + | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-image6.png|800px]] </div> |

<div id="_Ref195524714" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="_Ref195524714" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

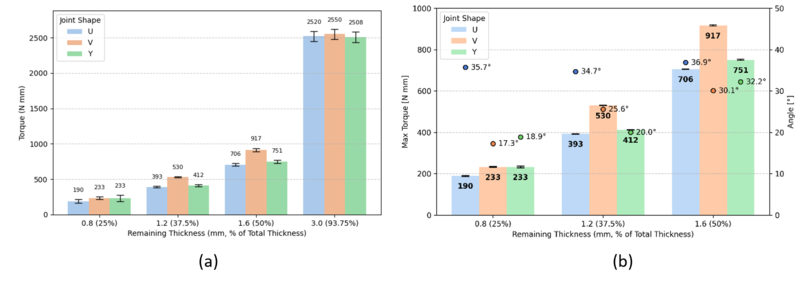

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 4: Summary of torsion tests as a function of shape (U, V, Y) and remaining thickness (S, M, L, and XL): (a) Average maximum torque; (b) Angle at maximum torque. Whisker lines correspond to Standard Deviations (SD).''</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 4: Summary of torsion tests as a function of shape (U, V, Y) and remaining thickness (S, M, L, and XL): (a) Average maximum torque; (b) Angle at maximum torque. Whisker lines correspond to Standard Deviations (SD).''</span></div> | ||

| + | |||

In addition to the maximum torque values, the analysis of the rotation angle at which the maximum torque occurs provides further insights into the deformation behavior of the specimens. Torsional tests also provided the angle of leg rotation at which the specimen experiences its initial peak torque before the edges of the notches come into contact and the structure stiffens. Results summarized in <span id='cite-_Ref195524714'></span>[[#_Ref195524714|Figure 4]] (b) indicate that the highest torsional rotation was achieved with the U-shaped specimens, regardless of the notch dimensions. In contrast, V- and Y-shape specimens displayed similar levels of rotation. The torsion test results emphasize the significant role of the notch shape in determining the initial deformation behavior. U-shaped specimens exhibit more significant initial rotation before stiffening, while V-shaped specimens show higher stiffness before reaching the torque peak. However, depending on the specific requirements, selecting the appropriate shape can be tailored to the desired behavior. | In addition to the maximum torque values, the analysis of the rotation angle at which the maximum torque occurs provides further insights into the deformation behavior of the specimens. Torsional tests also provided the angle of leg rotation at which the specimen experiences its initial peak torque before the edges of the notches come into contact and the structure stiffens. Results summarized in <span id='cite-_Ref195524714'></span>[[#_Ref195524714|Figure 4]] (b) indicate that the highest torsional rotation was achieved with the U-shaped specimens, regardless of the notch dimensions. In contrast, V- and Y-shape specimens displayed similar levels of rotation. The torsion test results emphasize the significant role of the notch shape in determining the initial deformation behavior. U-shaped specimens exhibit more significant initial rotation before stiffening, while V-shaped specimens show higher stiffness before reaching the torque peak. However, depending on the specific requirements, selecting the appropriate shape can be tailored to the desired behavior. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 73: | ||

The cantilever bending tests provided valuable insights into the remaining strength and mechanical response once the specimens have reached an initial deformed shape resulting from the torque application described in the previous section. The specimens tested under torque were subjected to bending in a cantilever configuration (see <span id='cite-_Ref195092263'></span>[[#_Ref195092263|Figure 3]] (b)) to determine the stiffness and maximum force characteristics that the different notch sizes and shapes can still carry out. <span id='cite-_Ref195537729'></span>[[#_Ref195537729|Figure 5]] shows close-up views of deflected shapes before and after the notch's edges come in contact during the cantilever bending tests, highlighting the material failure after the post-contact. | The cantilever bending tests provided valuable insights into the remaining strength and mechanical response once the specimens have reached an initial deformed shape resulting from the torque application described in the previous section. The specimens tested under torque were subjected to bending in a cantilever configuration (see <span id='cite-_Ref195092263'></span>[[#_Ref195092263|Figure 3]] (b)) to determine the stiffness and maximum force characteristics that the different notch sizes and shapes can still carry out. <span id='cite-_Ref195537729'></span>[[#_Ref195537729|Figure 5]] shows close-up views of deflected shapes before and after the notch's edges come in contact during the cantilever bending tests, highlighting the material failure after the post-contact. | ||

| − | < | + | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> |

| − | + | [[File:Draft_Dolz_104064930_4679_Figure_5.png|center|800px]]</div> | |

| + | |||

| + | <div id="_Ref195524714" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| + | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 5: Deflection evolution of U-, V- and Y-shaped specimens during cantilever bending testing. Medium size remaining thickness (1.2 mm).''</span></div> | ||

| + | |||

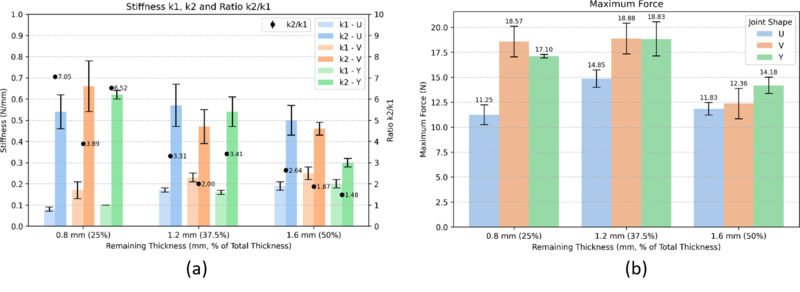

<span id='_bookmark7'></span>Force-deflection curves obtained from cantilever tests showed two distinctive slopes representative of the specimen stiffness. The shallower slope corresponds to the material's stiffness before contact between the notch edges occurs (''k''<sub>1</sub>), while the second stiffness (''k''<sub>2</sub>) reflects the increased stiffness due to structural contact between the notch's edges and surfaces. <span id='cite-_Ref195523847'></span>[[#_Ref195523847|Figure 6]] (a) summarizes the magnitude of each stiffness and the ratio between slopes (''k''<sub>2</sub>/''k''<sub>1</sub>) calculated to determine the increase in stiffness after contact. <span id='cite-_Ref195523847'></span>[[#_Ref195523847|Figure 6]] (b) summarizes the maximum force reached for each thickness and notch shape. | <span id='_bookmark7'></span>Force-deflection curves obtained from cantilever tests showed two distinctive slopes representative of the specimen stiffness. The shallower slope corresponds to the material's stiffness before contact between the notch edges occurs (''k''<sub>1</sub>), while the second stiffness (''k''<sub>2</sub>) reflects the increased stiffness due to structural contact between the notch's edges and surfaces. <span id='cite-_Ref195523847'></span>[[#_Ref195523847|Figure 6]] (a) summarizes the magnitude of each stiffness and the ratio between slopes (''k''<sub>2</sub>/''k''<sub>1</sub>) calculated to determine the increase in stiffness after contact. <span id='cite-_Ref195523847'></span>[[#_Ref195523847|Figure 6]] (b) summarizes the maximum force reached for each thickness and notch shape. | ||

| − | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-image8.png|center| | + | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-image8.png|center|800px]] |

<div id="_Ref195523847" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="_Ref195523847" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 6: Cantilever bending tests: (a) Comparison of the first and second stiffness values (k1 and k2), along with their ratios; (b) Compilation of average maximum forces reached by the specimens, categorized by shapes and thicknesses. Whisker lines correspond to Standard Deviations (SD).''</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 6: Cantilever bending tests: (a) Comparison of the first and second stiffness values (k1 and k2), along with their ratios; (b) Compilation of average maximum forces reached by the specimens, categorized by shapes and thicknesses. Whisker lines correspond to Standard Deviations (SD).''</span></div> | ||

| + | |||

Results show that the increase in ''k''<sub>2</sub> compared to ''k''<sub>1</sub> is particularly important because it implies that while the specimen can initially deform more easily, its behavior changes after contact, becoming much stiffer and potentially preventing further deformation. Moreover, the ''k''<sub>2</sub>/''k''<sub>1</sub> ratios decrease as the notch thickness increases, suggesting that the specimen is much stiffer from the start, and the change in stiffness after contact is relatively less pronounced. | Results show that the increase in ''k''<sub>2</sub> compared to ''k''<sub>1</sub> is particularly important because it implies that while the specimen can initially deform more easily, its behavior changes after contact, becoming much stiffer and potentially preventing further deformation. Moreover, the ''k''<sub>2</sub>/''k''<sub>1</sub> ratios decrease as the notch thickness increases, suggesting that the specimen is much stiffer from the start, and the change in stiffness after contact is relatively less pronounced. | ||

| Line 81: | Line 96: | ||

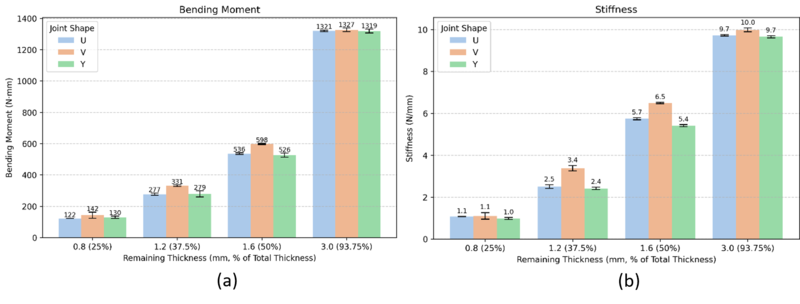

The four-point bending test results also provide insights into the structural behavior of different specimen notch shapes and thicknesses. Four-point bending tests were conducted with new, unbent specimens (shown in <span id='cite-_Ref195092263'></span>[[#_Ref195092263|Figure 3]] (c)) to compare the performance of specimens subjected to torsion, followed by cantilevered bending presented in the previous sections. As seen in the earlier sections, the maximum bending moments presented in <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (a) exhibit a clear dependency on specimen shape and thickness. However, the dependency seemed stronger for the notch size rather than the shape. Again, the V-shaped specimens exhibited the highest bending moment and stiffness, as shown in <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (a) and <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (b). Moreover, the maximum bending moment for specimens 3mm of remaining material is nearly identical (~1320 N.mm), indicating, as expected, a superior load-bearing capacity. | The four-point bending test results also provide insights into the structural behavior of different specimen notch shapes and thicknesses. Four-point bending tests were conducted with new, unbent specimens (shown in <span id='cite-_Ref195092263'></span>[[#_Ref195092263|Figure 3]] (c)) to compare the performance of specimens subjected to torsion, followed by cantilevered bending presented in the previous sections. As seen in the earlier sections, the maximum bending moments presented in <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (a) exhibit a clear dependency on specimen shape and thickness. However, the dependency seemed stronger for the notch size rather than the shape. Again, the V-shaped specimens exhibited the highest bending moment and stiffness, as shown in <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (a) and <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (b). Moreover, the maximum bending moment for specimens 3mm of remaining material is nearly identical (~1320 N.mm), indicating, as expected, a superior load-bearing capacity. | ||

| − | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-image9.png| | + | [[Image:Draft_Dolz_104064930-image9.png|center|800px]] |

<div id="_Ref195524170" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="_Ref195524170" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

<span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 7: Four-point bending tests: (a) Maximum bending moment; (b) k1 stiffness, as a function of remaining thickness and notch shapes. Whisker lines correspond to Standard Deviations (SD).''</span></div> | <span style="text-align: center; font-size: 75%;">''Figure 7: Four-point bending tests: (a) Maximum bending moment; (b) k1 stiffness, as a function of remaining thickness and notch shapes. Whisker lines correspond to Standard Deviations (SD).''</span></div> | ||

| + | |||

Unlike the cantilever bending specimens, the four-point bending specimens only showed a constant single slope before reaching the peak bending moment. The stiffness values reveal distinct trends across specimen configurations, as summarized in <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (b). For small-thickness specimens, stiffness remains relatively low, ranging from 1.0 N/mm (Y<sub>S</sub>) to 1.10 N/mm (U<sub>S</sub> and V<sub>S</sub>). As the remaining thickness increases, stiffness grows significantly, reaching its highest value for V<sub>XL</sub> (10.0 N/mm), demonstrating the enhanced rigidity of thicker specimens. | Unlike the cantilever bending specimens, the four-point bending specimens only showed a constant single slope before reaching the peak bending moment. The stiffness values reveal distinct trends across specimen configurations, as summarized in <span id='cite-_Ref195524170'></span>[[#_Ref195524170|Figure 7]] (b). For small-thickness specimens, stiffness remains relatively low, ranging from 1.0 N/mm (Y<sub>S</sub>) to 1.10 N/mm (U<sub>S</sub> and V<sub>S</sub>). As the remaining thickness increases, stiffness grows significantly, reaching its highest value for V<sub>XL</sub> (10.0 N/mm), demonstrating the enhanced rigidity of thicker specimens. | ||

Revision as of 21:35, 14 April 2025

1. Introduction

Among various additive manufacturing techniques, Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) has become a widely used method for producing polymer-based composites reinforced with fibers. These fiber-reinforced 3D-printed structures exhibit enhanced mechanical properties such as stiffness, strength, and impact resistance, making them attractive for engineering applications ranging from aerospace to biomedical devices [1]–[6]. However, challenges related to anisotropy, interlayer bonding, and mechanical performance under complex loading conditions persist. The inherent anisotropy introduced by the layer-by-layer deposition process significantly influences their mechanical behavior, affecting both in-plane and out-of-plane properties [3], [7]–[9]. Previous studies have addressed various factors that impact the mechanical properties of 3D-printed composites, such as fiber orientation, interlayer bonding, print parameters, and material selection [10]. Despite these challenges, 3D printing enables the fabrication of previously unfeasible structures, taking advantage of the ability to deposit material selectively to achieve desired mechanical behavior. This flexibility opens new opportunities for optimizing structural performance and developing novel engineering solutions.

One promising avenue for addressing these challenges is the integration of kirigami-inspired designs into 3D-printed composite structures. Kirigami, a variation of origami that involves cutting and folding materials to create deployable structures, has gained considerable attention due to its ability to achieve tunable mechanical properties and unique deformation mechanisms. By leveraging kirigami principles, it is possible to enhance flexibility, energy absorption, and failure control in fiber-reinforced 3D-printed composites [11]. This integration opens new possibilities for lightweight deployable structures in soft robotics, aerospace components, and civil engineering applications. Despite the potential advantages, incorporating kirigami-inspired features into fiber-reinforced composites presents several challenges. Traditional kirigami structures often rely on plastic deformation of folding regions and joints, which can lead to failure by fatigue and reduced durability over time. In fiber-reinforced composites, the anisotropic nature of the material further complicates deformation behavior, making necessary novel approaches for optimizing joint design, load distribution, and failure resistance. Additionally, the layer-by-layer nature of 3D printing introduces interfacial weaknesses that can compromise structural integrity, particularly in applications requiring repeated deployment and reconfiguration.

Kirigami structures offer advantages such as relatively simple manufacturability, low-energy initial deployment, high load-bearing capacity, and deformation energy absorption once deployed and formed into a three-dimensional structure. These properties make them attractive for applications in aerospace, biomedical devices, and soft robotics [11]–[15], where initial compactness, lightweight, and portability are highly desired features. In this regard, a key advantage of kirigami-based structures is their ability to be transported in a compact, flat state and then deployed into their functional three-dimensional configurations. This characteristic reduces storage and transportation costs while enabling adaptability in constrained environments. However, one of the major challenges in kirigami-based structures is the formation of plastic hinges during deployment. Repeated folding and unfolding in traditional kirigami can lead to material fatigue and plasticity-related damage, ultimately reducing the structure's reliability and lifespan. This issue becomes even more critical when implementing kirigami with fiber-reinforced composites, where material anisotropy and layer adhesion further complicate mechanical performance. While kirigami-based structures have been explored in metallic and polymeric materials, their implementation in fiber-reinforced 3D-printed composites remains largely unexplored [12], [16], [17]. Integrating fiber reinforcement into kirigami structures presents opportunities for improving mechanical performance by optimizing load distribution, reducing stress concentrations at folds, and enhancing failure resistance.

One of the most critical aspects of 3D-printed kirigami composite structures is the design of their joints and interlayer bonding, which dictate their deployability and mechanical robustness. Traditional kirigami designs rely on thin plastic hinges or stress concentration regions for flexibility. Still, these features can be susceptible to damage when subjected to cyclic or high-stress loading conditions [11], [18], [19]. Strategies such as modifying printing parameters, incorporating mechanical interlocks, and utilizing post-processing treatments have been proposed to enhance joint performance [20], [21]. Still, their effectiveness in kirigami-inspired structures has not been extensively studied. The need for novel yet simple and reliable joint designs that balance flexibility and strength remains a major challenge in the field. Figure 1 presents a preliminary 3D-printed kirigami design adopted from the literature [11], highlighting the flat initial state, the deployed state, and the position of the plastic joints under consideration in this study.

This study presents an initial investigation of the mechanical behavior of 3D-printed polymeric joints with different notch geometries designed to behave as plastic hinges when subjected to various bending loading configurations. These joints mimic the mechanical behavior of joints needed to deploy kirigami-inspired designs.

2. Experimental Setup

2.1 Specimen Design and Manufacturing

A series of prismatic specimens (127 mm long, 12.7 mm wide, and 3.2 mm thick, shown in Figure 2) were adopted for the tests performed in this study. The specimen dimensions are based on dimensions specified in the ASTM D790-17 standard. The prismatic specimens included three distinct notch geometries: U-shaped, V-shaped, and Y-shaped notches (see Figure 2). The notch depths varied from 1.6 mm, 1.2 mm, 0.8 mm, and 0.2 mm, corresponding to the remaining material thickness after creating the notch. For each remaining thickness, a corresponding name was assigned: 0.8 mm is referred to as small (S), 1.2 mm as medium (M), 1.6 mm as large (L), and 3 mm as extra-large (XL).

The test specimens were manufactured using Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) with a consumer-grade 3D printer (Creality, Ender E-S1-Pro), which allows for detailed layer-by-layer printing of polymer materials. A polylactic acid (PLA), 1.75 mm in diameter filament, was utilized to manufacture specimens as part of a preliminary evaluation of notch designs. To ensure the material's optimal behavior during printing, it was stored in a dry environment to prevent moisture absorption, which could otherwise lead to defects in the printed parts and inconsistencies in mechanical properties. The printing process was conducted with a layer height of 0.2 mm and a printing speed of 50 mm/sec, which are typical values for acceptable print quality at a reasonable printing time. The layer height was chosen to ensure that the details of the notch geometries were represented while maintaining an efficient production time. A 100% infill density was also selected to maximize the samples' internal homogeneity and mechanical resistance. Five specimens were printed for each configuration to ensure repeatability and account for any variability in the printing process.

2.2 Mechanical Testing Procedures

The specimens are subjected to torsion, cantilever bending, and four-point bending testing. The testing conditions corresponding to each test are presented in Figure 3. Each test was performed under displacement-controlled conditions to assess the mechanical response of the specimens accurately. The testing machine used for the general tests was a tabletop universal testing machine (Shimadzu EZ-LX, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a 2 kN load cell with a 0.5% load resolution. A torque tester (TT05-100, Mark-10, Copiague, NY) equipped with an 11500 N.mm torque load cell and 5 N.mm resolution was used for torsion tests and allowed for controlled rotational displacement and torque measurement. Each test included the following key features:

- Torsion Test: The specimens were clamped at one end while the opposite end was subjected to a controlled rotational displacement at a constant angular velocity, as shown in Figure 3(a). The torque (in N.mm) required to induce a quasi-static rotation of 90° was recorded to evaluate each geometry's torsional stiffness and failure characteristics.

- Cantilever Bending Test: The specimen was rigidly fixed at one end while a load was applied at a point 20 mm from the clamped edge, producing a bending moment, as shown in Figure 3(b). The quasi-static nature of the test stems from the slow (2 mm/min), controlled application of force, ensuring a gradual specimen deformation. The fixed-free configuration allows for a pure bending moment to develop along the specimen length, effectively evaluating the flexural response of the different notch geometries. The force recorded by the testing machine was used to calculate the resulting bending moments.

- Four-Point Bending Test: This test is based on the ASTM D6272-17 standard, in which the specimens are placed onto two outer supports while two inner loading points apply force at a constant displacement rate (1 mm/min) (Figure 3 (c)). The distance between lower supports was 100 mm, and the upper loading points were positioned at 25 mm from each lower support. This configuration ensured a uniform bending moment in the central section of the specimen, minimizing shear effects and allowing for a more accurate evaluation of flexural properties.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Torsion test results

The torsion test results reveal distinct trends in the maximum torque and variability across different specimen thicknesses and shapes (U, V, and Y). The maximum torque consistently increases with the specimen's remaining thickness, demonstrating the expected enhancement in mechanical resistance as the material bearing the torsional loads increases, as summarized in Figure 4 (a). However, the magnitude of this increase varies among the different specimen shapes. Test results indicate that the V-shaped specimens exhibit the highest torque across all thicknesses, while the U-shaped specimens generally present the lowest values. The Y-shaped specimens fall in between, with increased variability.

In addition to the maximum torque values, the analysis of the rotation angle at which the maximum torque occurs provides further insights into the deformation behavior of the specimens. Torsional tests also provided the angle of leg rotation at which the specimen experiences its initial peak torque before the edges of the notches come into contact and the structure stiffens. Results summarized in Figure 4 (b) indicate that the highest torsional rotation was achieved with the U-shaped specimens, regardless of the notch dimensions. In contrast, V- and Y-shape specimens displayed similar levels of rotation. The torsion test results emphasize the significant role of the notch shape in determining the initial deformation behavior. U-shaped specimens exhibit more significant initial rotation before stiffening, while V-shaped specimens show higher stiffness before reaching the torque peak. However, depending on the specific requirements, selecting the appropriate shape can be tailored to the desired behavior.

3.2 Cantilever bending test results

The cantilever bending tests provided valuable insights into the remaining strength and mechanical response once the specimens have reached an initial deformed shape resulting from the torque application described in the previous section. The specimens tested under torque were subjected to bending in a cantilever configuration (see Figure 3 (b)) to determine the stiffness and maximum force characteristics that the different notch sizes and shapes can still carry out. Figure 5 shows close-up views of deflected shapes before and after the notch's edges come in contact during the cantilever bending tests, highlighting the material failure after the post-contact.

Force-deflection curves obtained from cantilever tests showed two distinctive slopes representative of the specimen stiffness. The shallower slope corresponds to the material's stiffness before contact between the notch edges occurs (k1), while the second stiffness (k2) reflects the increased stiffness due to structural contact between the notch's edges and surfaces. Figure 6 (a) summarizes the magnitude of each stiffness and the ratio between slopes (k2/k1) calculated to determine the increase in stiffness after contact. Figure 6 (b) summarizes the maximum force reached for each thickness and notch shape.

Results show that the increase in k2 compared to k1 is particularly important because it implies that while the specimen can initially deform more easily, its behavior changes after contact, becoming much stiffer and potentially preventing further deformation. Moreover, the k2/k1 ratios decrease as the notch thickness increases, suggesting that the specimen is much stiffer from the start, and the change in stiffness after contact is relatively less pronounced.

Regarding maximum force, the cantilever bending test results suggest that the V-shaped specimens exhibit the highest maximum force for small and medium thicknesses, making them structurally advantageous for load-bearing applications. These results indicate that the joint's mechanical behavior depends on shape and thickness, which should be carefully considered in design applications.

3.3 Four-Point Bending Test Results

The four-point bending test results also provide insights into the structural behavior of different specimen notch shapes and thicknesses. Four-point bending tests were conducted with new, unbent specimens (shown in Figure 3 (c)) to compare the performance of specimens subjected to torsion, followed by cantilevered bending presented in the previous sections. As seen in the earlier sections, the maximum bending moments presented in Figure 7 (a) exhibit a clear dependency on specimen shape and thickness. However, the dependency seemed stronger for the notch size rather than the shape. Again, the V-shaped specimens exhibited the highest bending moment and stiffness, as shown in Figure 7 (a) and Figure 7 (b). Moreover, the maximum bending moment for specimens 3mm of remaining material is nearly identical (~1320 N.mm), indicating, as expected, a superior load-bearing capacity.

Unlike the cantilever bending specimens, the four-point bending specimens only showed a constant single slope before reaching the peak bending moment. The stiffness values reveal distinct trends across specimen configurations, as summarized in Figure 7 (b). For small-thickness specimens, stiffness remains relatively low, ranging from 1.0 N/mm (YS) to 1.10 N/mm (US and VS). As the remaining thickness increases, stiffness grows significantly, reaching its highest value for VXL (10.0 N/mm), demonstrating the enhanced rigidity of thicker specimens.

4. Preliminary conclusions

The experimental results from the three mechanical tests – torsion, cantilever bending, and four-point bending – revealed distinct yet complementary mechanical behaviors, highlighting the influence of specimen geometry and boundary conditions on the structural behavior of the test specimens.

A direct comparison of the maximum torsional moments obtained from the torsion tests and the maximum bending moments obtained from the four-point bending tests shows that the highest values were consistently achieved in the torsional tests across all specimen configurations (see Figure 4 (a) vs. Figure 7 (a)). These differences are attributed to the distinct boundary conditions of each test. The specimen undergoes pure rotational loading in the torsion test, distributing stress uniformly along its width. In contrast, the four-point bending test induces a bending moment through localized loading points, leading to different stress distributions that influence the mechanical response.

Both the cantilever bending and four-point bending tests evaluate flexural behavior; however, the results differ due to the variation in boundary conditions and the specimen loading history. The cantilever bending test involved specimens previously subjected to torsion, placed in a fixed-free condition, where one end of the specimen is constrained while the other is subjected to a force, inducing both bending and shear effects. On the other hand, the four-point bending test involved new, unbent specimens subjected to two symmetric loads, resulting in a pure bending region between the loading points with minimal shear influence. Despite these differences, the trends observed in both tests are consistent.

In terms of notch shape, V-shaped specimens generally demonstrated higher stiffness and load-bearing capacity compared to U and Y shapes, as reflected in both tests. Also, regarding remaining thickness, results showed that as the thickness increased, maximum force, stiffness, and torque values also increased, confirming the expected strengthening effect of larger cross-sections. Finally, considering all the test results, the following key trends are identified:

- Shape dependence: The V-shaped specimens exhibited superior mechanical behavior regarding maximum force, torque, and stiffness. The U-shaped specimens showed higher deformation capacities, making them more suitable for increased flexibility applications.

- Remaining thickness influence: Increasing the specimen's remaining thickness (or reducing the notch depth) consistently improved mechanical strength, stiffness, and load-bearing capacity.

- Boundary condition effects: While absolute values varied due to differences in loading and support conditions, each specimen shape and notch dimension's relative mechanical behavior remained consistent across the different test configurations.

These findings provide valuable insights for selecting shapes and thicknesses of 3D-printed plastic joints necessary to produce easily deployable yet structurally robust kirigami structures for different engineering applications.

5. References

[1] W. Zhong, F. Li, Z. Zhang, L. Song, and Z. Li, “Short fiber reinforced composites for fused deposition modeling,” Mater. Sci. Eng. A, vol. 301, no. 2, pp. 125–130, 2001.

[2] F. Van Der Klift, Y. Koga, A. Todoroki, M. Ueda, Y. Hirano, and R. Matsuzaki, “3D Printing of Continuous Carbon Fibre Reinforced Thermo-Plastic (CFRTP) Tensile Test Specimens,” Open J. Compos. Mater., vol. 06, no. 01, pp. 18–27, 2016.

[3] F. Ning, W. Cong, J. Qiu, J. Wei, and S. Wang, “Additive manufacturing of carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites using fused deposition modeling,” Compos. Part B Eng., vol. 80, pp. 369–378, 2015.

[4] M. Chapiro, “Current achievements and future outlook for composites in 3D printing,” Reinf. Plast., vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 372–375, 2016.

[5] X. Wang, M. Jiang, Z. Zhou, J. Gou, and D. Hui, “3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective,” Compos. Part B Eng., vol. 110, pp. 442–458, 2017.

[6] G. Liao et al., “Properties of oriented carbon fiber/polyamide 12 composite parts fabricated by fused deposition modeling,” Mater. Des., vol. 139, pp. 283–292, Feb. 2018.

[7] X. Tian, T. Liu, C. Yang, Q. Wang, and D. Li, “Interface and performance of 3D printed continuous carbon fiber reinforced PLA composites,” Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf., vol. 88, pp. 198–205, 2016.

[8] N. Li, Y. Li, and S. Liu, “Rapid prototyping of continuous carbon fiber reinforced polylactic acid composites by 3D printing,” J. Mater. Process. Technol., vol. 238, pp. 218–225, 2016.

[9] C. Yang, X. Tian, T. Liu, Y. Cao, and D. Li, “3D printing for continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites: Mechanism and performance,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 209–215, 2017.

[10] Y. Fu and X. Yao, “Multi-scale analysis for 3D printed continuous fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites,” Compos. Sci. Technol., vol. 216, no. October, p. 109065, 2021.

[11] I. M. de Oliveira, E. M. Sosa, E. Baker, and S. Adriaenssens, “Experimental and numerical investigation of a rotational kirigami system,” Thin-Walled Struct., vol. 192, Nov. 2023.

[12] T. C. Shyu et al., “A kirigami approach to engineering elasticity in nanocomposites through patterned defects,” Nat. Mater., vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 785–789, Aug. 2015.

[13] I. M. De Oliveira, E. Baker, and S. Adriaenssens, “The effect of geometric tiling parameters on the stiffness of a rotational kirigami system,” in Redefining the Art of Structural Desig, 2024.

[14] J. Tao, H. Khosravi, V. Deshpande, and S. Li, “Engineering by Cuts: How Kirigami Principle Enables Unique Mechanical Properties and Functionalities,” Advanced Science, vol. 10, no. 1. John Wiley and Sons Inc, 04-Jan-2023.

[15] P. Block et al., “A foldable temporary shelter design,” in Redefining the Art of Structural Design, 2024.

[16] H. Zhang and J. Paik, “Kirigami Design and Modeling for Strong, Lightweight Metamaterials,” Adv. Funct. Mater., vol. 32, no. 21, May 2022.

[17] X. Zhang et al., “Kirigami-based metastructures with programmable multistability,” 2022.

[18] M. G. Walker and K. A. Seffen, “The Mechanics of Metallic Folds,” in Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Duke University, 2016.

[19] S. Sadik, M. G. Walker, and M. A. Dias, “On local kirigami mechanics II: Stretchable creased solutions,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, vol. 161, Apr. 2022.

[20] L. Wang, W. Du, P. He, and M. Yang, “Topology Optimization and 3D Printing of Three-Branch Joints in Treelike Structures,” J. Struct. Eng., vol. 146, no. 1, Jan. 2020.

[21] A. Spaggiari and F. Favali, “Evaluation of polymeric 3D printed adhesively bonded joints: effect of joint morphology and mechanical interlocking,” Rapid Prototyp. J., vol. 28, no. 8, pp. 1437–1451, Aug. 2022.

Document information

Published on 21/01/26

Accepted on 23/06/25

Submitted on 12/05/25

Volume 09 - Comunicaciones MatComp25 (2025), Issue Núm. 3 - Caracterización Experimental, 2026

DOI: 10.23967/r.matcomp.2025.09.27

Licence: Other