m (removed incomplete data) (Tag: Visual edit) |

m (placed Figure caption below the image) (Tag: Visual edit) |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

<div id="_Ref173829759" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="_Ref173829759" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | + | <nowiki> </nowiki>[[Image:Draft_Shimpi_734787592-image2.png|600px]] Figure 2. Simplified single lap shear specimen | |

| + | </div> | ||

:'''2.4.''' Gas permeability analysis''': ''' | :'''2.4.''' Gas permeability analysis''': ''' | ||

Revision as of 15:09, 10 April 2025

1. Introduction:

The increasing demand for hydrogen gas as fuel has led researchers to develop lighter and stronger materials, intended for safely storing hydrogen in liquified form at cryogenic temperatures. Hydrogen exists as diatomic molecule in atmosphere with lowest molecular diameter, thus the materials required for storing hydrogen are required to have higher gas permeability properties [1]. One of the most preferred and lightest material is carbon fibre composite, whose properties can be customized according to the pressure requirements for storing liquified hydrogen [2], [3]. Based on the percentage use of carbon composite, the hydrogen tanks are differentiated in 5 categories. Type I tank is manufactured solely using aluminium or steel alloys (Al 6061, AA7175, AA6XX series etc) [4]. Type II and III use filament wound carbon or glass fibres either in dome region or on overall tank, respectively. Type IV tank is manufactured using polymer liner and carbon/glass composite by tow winding on the surface. Type V is all composite tank without any liner. With increasing composite content in the tank material, the gravimetric index of the tank also increases [5].

The gas (and particularly hydrogen) permeability of the Type IV and Type V tanks is critical in determining the safety, efficiency, and durability of high-pressure storage tanks. According to US Department of Energy for their Hydrogen energy program, the allowable gas permeation levels are 0.05 (g/h)/kg in a carbon composite pressure vessel [6]. Temperature, pressure, and material properties are the main factors influencing hydrogen permeability in Type IV and Type V tanks [7].

Project OVERLEAF2 is aimed at developing Type V cryogenic liquid hydrogen storage tank with working pressure of 6 bar. Under this project, thermoplastic composites with carbon fibre as reinforcement and polyamide 11 (PA11) as matrix were developed to resist the cryogenic temperature of 120K while maintaining bust pressure of 350 Mpa and maximum hydrogen leakage rate of 4 x 10-7 mol H2/s. Automated tape layup (ATL) technique with 6kW laser as heating source was used to manufacture the composites with quasi-isotropic layup sequence and treated in autoclave. The resulting composites were tested for hydrogen permeability and analysed for suitability of cryogenic liquid hydrogen storage.

(2) The OVERLEAF cryogenic tank for storing H2 in liquid form is patent-protected, based on a concept protected by an Aciturri patent (European Patent Number 22 382 492.1.)

2. Materials and methods:

PA11 impregnated unidirectional (UD) CF tape of 12.7 mm width were sourced from Arkema® (UDX™ Rilsan PA11) and Suprem ® (Suprem 11701). To study the relation between matrix plasticity, porosity and ATL process parameters in the composites, Arkema supplied 2 additional experimental versions of CF/PA11 tapes as listed in Table 1.

| Sample code | Tape | Supplier | Viscosity

(Pa˙s) |

Fiber volume content % |

| V1 | UDX Rilsan PA11 | Arkema® | 10 | 53 |

| V4 | Suprem 11701 | Suprem® | 150 | 57 |

Table 1. CF/PA11 thermoplastic tapes

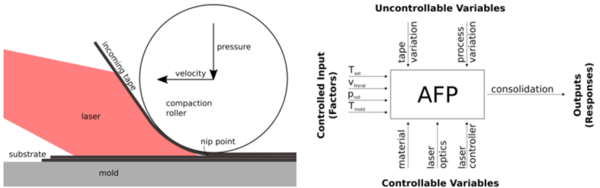

FANUC® R-2000iC/165Fi™ 6 axis robot with Laserline® 6kW diode laser heater was used to automate the manufacture the composites. The laser temperature was controlled via pyrometers mounted on the tape laying head in order to avoid overheating of the tape. Figure 1 shows the complete setup of the tape laying system.

The main process parameters for the tape layup are:

- Nip Point Temperature (°C)

- Layup Speed (mm/s)

- Compaction force or pressure (N or bar)

- 2.1. Microstructural analysis:

OLIMPUS GX71™ microscope was used to carry out microstructural analysis of the processed CF/PA11 tape. The microstructural analysis was done on 100, 200 and 500 magnifications. The results obtained helped to determine the porosity content of the final composite.

- 2.2. Thermal analysis:

Digital scanning calorimetry (DSC) Q20 V24.10 Build 122™ from TA Instrument® was used to characterize the glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm) and crystallinity of the unprocessed CF/PA11 tapes according to UNE-EN ISO 11357 test standard. The samples were subjected to a pre-drying cycle of 80°C for 6 to 8 hours. After this step, a nitrogen atmosphere was used and the samples were heated to 250°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min, holding isothermal for 15 min, and cooling down with a rate of 10 °C/min.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) Q500 V20.13 Build 39™ from TA Instruments® was used for testing the thermal degradation of the unprocessed tapes according to UNE-EN ISO 11358 test standard. The samples were subjected to a pre-drying cycle of 80°C for 6 to 8 hours. A heating ramp from room temperature to 950 °C was carried out with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. This test was carried out in an inert atmosphere of nitrogen from room temperature to 650°C and from 650°C to 950°C under oxidizing atmosphere.

- 2.3. Mechanical test:

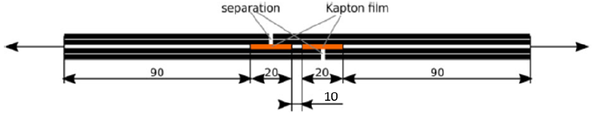

Simplified single lap shear (SLS) were conducted on the manufactured composite samples to determine the effect of ATL process parameters on mechanical properties of the composites. For SLS, samples of 230 mm x 25 mm were manufactured with plies in 0 direction and shear zone of 25 mm x 10 mm as shown in Figure 2 using polyimide Kapton™ film.

- 2.4. Gas permeability analysis:

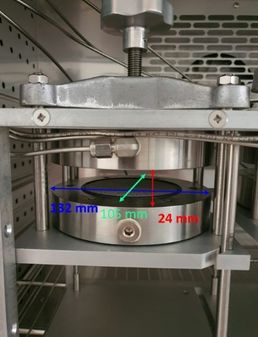

Hydrogen permeability measurements were carried out using Versaperm® MkVI™ Manometric Permeability Meter according to ASTM D1434-23 test standard. The permeation measurements were performed using H2 at 1.5 and 2 bar. The common sample dimension is 100 x 100 mm2 or 100 mm diameter. In Figure 3 a detailed description of the permeation cell dimension is shown. Permeability tests were carried out at 23°C.

The permeances in metric system P [mol/m2·s·Pa], where d is the thickness of the sample – these values are directly obtained from the Versaprem software.

Permeability in SI units (Barrer) is calculated with the formula 2.1 and 2.2:

P(Barrer)×33.49 = P(SI)(fmol/(m2×s×Pa)) (2.1)

Where:

∆ P = Pressure difference of both sides of the sample (Pa)

A = Area of the sample: 0.005026548 m2

T = Temperature: 23°C (296.15 K)

3. Results and discussion:

- 3.1. Thermal Characterization:

The results of the thermal characterization by DSC and TGA analysis show that operating temperature for PA11 matrix is in the range of 200°-300° C as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. DSC and TGA analysis of unprocessed CF/PA11 tape

| Sample code | Tg (°C) | Melting temperature (°C) | % polymer | % crystallinity | Degradation temperature (°C) |

| V1 | 46.64 | 189.42 | 0.47 | 23.9 | 358.0 |

| V4 | 94.44 | 188.45 | 0.57 | 22.0 | 432.3 |

For determining the ATL process parameters to achieve in-situ consolidated composites having maximum hydrogen permeance of 4.0 x 10-7 mol H2/s, temperature and speed were optimized as shown in Table 3, according to the maximum SLS criteria since these are key variables for the consolidation at constant contact force of 500 N.

Table 3. Process window for AFP trials

| Trial | Temperature (°C) | Speed (mm/s) | Number of samples | V1

SLS [MPa] |

V4

SLS [MPa] |

| 1 | 200 | 100 | 4 | 7.57 | 16.07 |

| 2 | 240 | 100 | 4 | 44.02 | 17.87 |

| 3 | 280 | 100 | 4 | 29.27 | 16.81 |

| 4 | 200 | 150 | 4 | 26.89 | 16.36 |

| 5 | 240 | 150 | 4 | 40.75 | 16.43 |

| 6 | 280 | 150 | 4 | 43.97 | 14.83 |

| 7 | 200 | 200 | 4 | 38.72 | 13.28 |

| 8 | 240 | 200 | 4 | 34.08 | 14.92 |

| 9 | 280 | 200 | 4 | 39.29 | 15.42 |

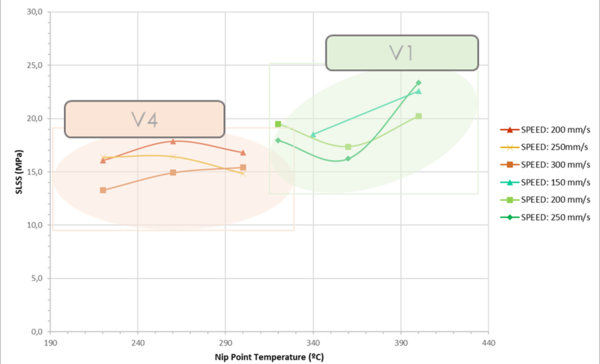

Based on the data of Table 3, comparing the SLSS results of v1 and v4 as shown in Figure 4, it was observed that v1 had 22.4% more strength than v4, however v4 can be processed at higher speeds and lower nip point temperature. In general, a direct and increasing relationship between speed and nip point temperature was observed for both versions.

Figure 4. Single Lap Shear Strength (SLSS) comparison between v1 and v4.

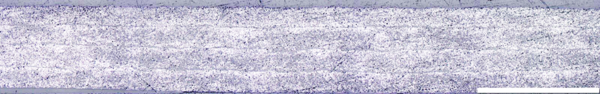

- 3.2. Microstructural analysis:

The microstructural analysis detailed in Figure 5 showed that maximum porosity levels of V1 and V4 below 1% were achieved with the combination of:

- 1) V1: 240⁰C nip point temperature, 100 mm/s speed

- 2) V4: 260°C nip point temperature, 300 mm/s speed

With this characterisation, the optimised parameters were defined and panels for hydrogen permeability were manufactured.

a |

b |

Figure 5. a) cross section of SLSS sample Version 1 PA11-CF, b) cross section of a SLSS sample of Version 4 PA11-CF

- 3.3. Hydrogen Permeability:

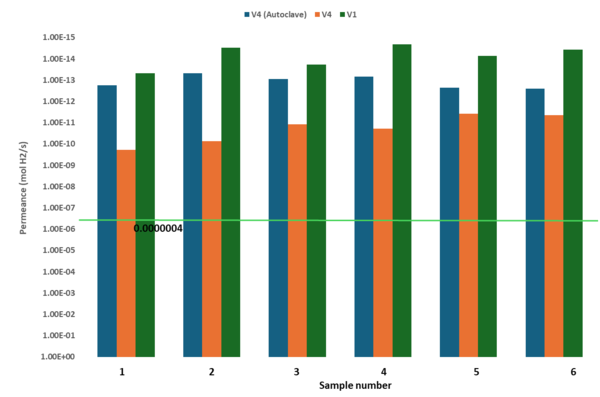

The hydrogen permeablity of V1 and V4 produced by optimised process parameters surpassed the required level of 4 x 10-7 mol H2/s (green line) as shown in Table 4 and Figure 6. As reference, an extra set of V4 samples were treated in autoclave (details) to compare the in-situ consolidation levels.

Table 4. Hydrogen permeability of in-situ consolidated CF/PA11 thermoplastic composites.

| Sample | V1

mol H2/s |

V4

mol H2/s |

V4 (autoclave) mol H2/s |

| 1 | 4.73E-14 | 1.89E-10 | 1.75E-13 |

| 2 | 3.08E-15 | 7.46E-11 | 4.78E-14 |

| 3 | 1.91E-14 | 1.16E-11 | 9.02E-14 |

| 4 | 2.10E-15 | 1.89E-11 | 6.90E-14 |

| 5 | 7.18E-15 | 3.76E-12 | 2.29E-13 |

| 6 | 3.76E-15 | 4.40E-12 | 2.50E-13 |

The V1 samples showed the least permeablity to hydrogen as compared to V4 and thus better in-situ consolidation. This can be attributed to lower viscosity of the PA11 matrix and thus more uniform wetting of the fibres resulting in lower porosity levels. On the other hand, the permeablity of V4 improved by factor of 77. 66 with autoclave post processing, indicating that matrix homogeneity plays a vital role in improving the gas permeablity of the thermoplastic composites.

Conclusions:

In this research work, CF/PA11 thermoplastic composites were manufactured using the commercial tapes from Arkema (UDX PA11) and experimental tape from Suprem using ATL with 6kW diode laser heating source. The unprocessed tapes were characterized for thermal properties using DSC and TGA, while the composites were characterized for mechanical properties by SLS and microscopic analysis in addition to hydrogen permeance in gas chamber. The following conclusions can be derived:

- The DSC analysis of as received tows showed that melting temperature was between 188.76 - 189.42°C, Tg between 45-46°C for v1 (10 Pa˙s viscosity); 91-96°C for v4 (150 Pa˙s viscosity). The TGA analysis showed that the degradation temperatures were between 358 - 434°C.

- The maximum porosity level of 1% was measured by microscopy analysis of V1 and V4.

- Based on the DSC and TGA analysis, process parameters of Temperature (T): [200 – 280]°C, Speed (𝑣𝑙𝑎𝑦𝑢𝑝): [100 – 200] mm/s were selected for v1 and Temperature (T): [220 – 300]°C, Speed (𝑣𝑙𝑎𝑦𝑢𝑝): [200 – 300] mm/s for v4 tows , with constant Compaction force (𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑙𝑙): [500] N, to make samples for SLSS tests. The following optimized process parameters were derived:

- V1: 240⁰C nip point temperature, 100 mm/s speed.

- V4: 280°C nip point temperature, 200 mm/s speed.

- The V1 and V4 composites manufactured by optimised process parameters satisfied the requirement of 4 x 10-7 mol H2/s with V1 showing the least permeablity value of 2.1 x 10-15 mol H2/s followed by V4 (autoclave) 4.78 x 10-14 mol H2/s and V4 3.76 x 10-12 mol H2/s.

REFERENCES:

[1] H. Hamori, H. Kumazawa, R. Higuchi, and T. Yokozeki, “Gas permeability of CFRP cross-ply laminates with thin-ply barrier layers under cryogenic and biaxial loading conditions,” Compos Struct, vol. 245, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.112326.

[2] A. Air, E. Oromiehie, and B. G. Prusty, “Design and manufacture of a Type V composite pressure vessel using automated fibre placement,” Compos B Eng, vol. 266, Nov. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.111027.

[3] H. S. Roh, T. Q. Hua, and R. K. Ahluwalia, “Optimization of carbon fiber usage in Type 4 hydrogen storage tanks for fuel cell automobiles,” in International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Sep. 2013, pp. 12795–12802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.07.016.

[4] M. P. Alves, W. Gul, C. A. Cimini Junior, and S. K. Ha, “A Review on Industrial Perspectives and Challenges on Material, Manufacturing, Design and Development of Compressed Hydrogen Storage Tanks for the Transportation Sector,” Jul. 01, 2022, MDPI. doi: 10.3390/en15145152.

[5] A. Air, M. Shamsuddoha, and B. Gangadhara Prusty, “A review of Type V composite pressure vessels and automated fibre placement based manufacturing,” Mar. 15, 2023, Elsevier Ltd. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110573.

[6] R. K. Ahluwalia, T. Q. Hua, and J. K. Peng, “On-board and Off-board performance of hydrogen storage options for light-duty vehicles,” Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 2891–2910, Feb. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.05.040.

[7] K. Kadri, A. Ben Abdallah, and S. Ballut, “Hydrogen Storage Vessels of Type 4 and Type 5,” in Hydrogen Technologies - Advances, Insights, and Applications, IntechOpen, 2024. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.1005520.

Document information

Published on 30/07/25

Accepted on 22/06/25

Submitted on 17/03/25

Volume 09 - Comunicaciones MatComp25 (2025), Issue Núm. 1 - Fabricación y Aplicaciones Industriales, 2025

DOI: 10.23967/r.matcomp.2025.09.05

Licence: Other

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?