m (small change in one stacking sequence that was wrong) (Tag: Visual edit) |

m (Marherna moved page Review 841175581933 to Martin Beato et al 2024a) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==1. Introduction== | ==1. Introduction== | ||

| Line 32: | Line 5: | ||

<div id="_GoBack" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="_GoBack" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image1.png|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure1" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure1" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 43: | Line 16: | ||

As it is described in detail in the paper of C Mittelstedt and W Becker, see <span id='cite-ref2'></span>[[#ref2|[2] ]], there are different ways to solve the edge effect problem. Classical laminate analysis cannot be used to capture the interlaminar stresses in a flat panel and the 3D constitutive equations for an orthotropic composite material lead to a complex set of differential equations that have not been solved yet. All the available solutions are based on some sort of simplifications that allow to obtain a solution close to the real problem. Based on the nature of the solution, methods can be separated in two different main groups: | As it is described in detail in the paper of C Mittelstedt and W Becker, see <span id='cite-ref2'></span>[[#ref2|[2] ]], there are different ways to solve the edge effect problem. Classical laminate analysis cannot be used to capture the interlaminar stresses in a flat panel and the 3D constitutive equations for an orthotropic composite material lead to a complex set of differential equations that have not been solved yet. All the available solutions are based on some sort of simplifications that allow to obtain a solution close to the real problem. Based on the nature of the solution, methods can be separated in two different main groups: | ||

| − | :* '''Closed-form solution''': In this group there are all the analytical methods that, based on some simplifications, obtain the interlaminar stresses, like the work of Puppo and Evensen, see <span id='cite-ref3'></span>[[#ref3|[3]]] or Pagano, mixing Mindlin laminate theory and finite element models <span id='cite-ref4'></span>[[#ref4| | + | :* '''Closed-form solution''': In this group there are all the analytical methods that, based on some simplifications, obtain the interlaminar stresses, like the work of Puppo and Evensen, see <span id='cite-ref3'></span>[[#ref3|[3]]] or Pagano, mixing Mindlin laminate theory and finite element models <span id='cite-ref4'></span>[[#ref4| ]]. Most of the methods of this group provide a fast an accurate solution but it fails to cover a wide range of use cases. For instance, they are usually limited to the stacking sequences tested, as they are mainly intended for research purpose. |

:* '''Finite Element models''': These model are well-known to solve solid mechanical problems and are able to predict free-edge effect with the proper element formulation and mesh refinement, so most of the works are focused on high order elements and meshing convergence strategy, see Vidal <span id='cite-ref5'></span>[[#ref5|[5]]]. Even if those methods can cover a wide range of stacking and loads, it requires a high amount of effort to set up the model, reducing the applicability for an industrial solution to be used for trade-offs and/or optimization. | :* '''Finite Element models''': These model are well-known to solve solid mechanical problems and are able to predict free-edge effect with the proper element formulation and mesh refinement, so most of the works are focused on high order elements and meshing convergence strategy, see Vidal <span id='cite-ref5'></span>[[#ref5|[5]]]. Even if those methods can cover a wide range of stacking and loads, it requires a high amount of effort to set up the model, reducing the applicability for an industrial solution to be used for trade-offs and/or optimization. | ||

| Line 54: | Line 27: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image2-c.png|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure2" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure2" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 37: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image3-c.png|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure3" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure3" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 76: | Line 49: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image4.PNG|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure4" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure4" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 82: | Line 55: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image5.PNG|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure5" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure5" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 92: | Line 65: | ||

In this section the effect of the stacking sequence and ply thickness will be studied. As this effect is generated due to the stiffness difference between two adjacent plies, ply orientation in the stacking will drastically influence the interlaminar stresses. All the results values displayed are normalized to facilitate the comparison between cases. | In this section the effect of the stacking sequence and ply thickness will be studied. As this effect is generated due to the stiffness difference between two adjacent plies, ply orientation in the stacking will drastically influence the interlaminar stresses. All the results values displayed are normalized to facilitate the comparison between cases. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

In this basic example a quasi-isotropic symmetrical laminate composed by 45°, -45°, 0° and 90° plies, can lead to different interlaminar values. First the following stacking will be studied: [45/ -45/ 0/ 90]<sub>s</sub>. This laminate concentrates two 90° plies at the center of the stacking, surrounded by 0° plies. As it can be shown in Figure 6, this generates an interlaminar σ<sub>z</sub> peak at the 90° plies location, whereas the interlaminar shear σ<sub>xz</sub> lies mainly in the 45/-45 package. | In this basic example a quasi-isotropic symmetrical laminate composed by 45°, -45°, 0° and 90° plies, can lead to different interlaminar values. First the following stacking will be studied: [45/ -45/ 0/ 90]<sub>s</sub>. This laminate concentrates two 90° plies at the center of the stacking, surrounded by 0° plies. As it can be shown in Figure 6, this generates an interlaminar σ<sub>z</sub> peak at the 90° plies location, whereas the interlaminar shear σ<sub>xz</sub> lies mainly in the 45/-45 package. | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image6.png|492px]] </div> |

<div id="figure6" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure6" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 106: | Line 77: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image7.png|504px]] </div> |

<div id="figure7" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure7" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 116: | Line 87: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image8.png|600px]] </div> |

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image9.png|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure8" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure8" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 131: | Line 102: | ||

Nevertheless, analyzing only max values can lead to wrong interpretation of the real phenomena as the stresses depicted here are the value obtain at y =0.1mm of the edge, but they are related to a stress concentration effect and decrease far from the edges. As it can be shown in the first laminate, the amount of plies that are suffering a positive σ<sub>z</sub> (tensile) covers almost 6 plies, reaching its peak at the 90 ply, whereas in the second stacking, only the 90° ply is under interlaminar stresses and it decreases outside this ply. This fact it crucial in order to understand the area of the stacking that is affected from free-edge effect Ply thickness effect. | Nevertheless, analyzing only max values can lead to wrong interpretation of the real phenomena as the stresses depicted here are the value obtain at y =0.1mm of the edge, but they are related to a stress concentration effect and decrease far from the edges. As it can be shown in the first laminate, the amount of plies that are suffering a positive σ<sub>z</sub> (tensile) covers almost 6 plies, reaching its peak at the 90 ply, whereas in the second stacking, only the 90° ply is under interlaminar stresses and it decreases outside this ply. This fact it crucial in order to understand the area of the stacking that is affected from free-edge effect Ply thickness effect. | ||

| − | Other interesting exercise can be performed when the ply thickness is modified: in this example two stacking with the same thickness and almost the same mechanical properties are compared. The main difference is in the ply thickness, the first stacking sequence has a cured ply thickness (CPT) of 0.25mm and a staking sequence: [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90], whereas second stacking is [45/0/-45/90/45/0/ | + | Other interesting exercise can be performed when the ply thickness is modified: in this example two stacking with the same thickness and almost the same mechanical properties are compared. The main difference is in the ply thickness, the first stacking sequence has a cured ply thickness (CPT) of 0.25mm and a staking sequence: [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90], whereas second stacking is [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90]s, of CPT 0.5 mm. |

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image10.png|600px]] </div> |

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Review_841175581933-image11.png|600px]] </div> |

<div id="figure9" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div id="figure9" class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| Line 143: | Line 114: | ||

<div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | <div class="center" style="width: auto; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"> | ||

| − | Top results: [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90]s, bottom [45/0/-45/90/45/0/ | + | Top results: [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90]s, bottom [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90]s.</div> |

As was previously described, main interlaminar stresses are located where 90° plies are. See Figure 9. Also, it can be noticed that as the ply thickness is duplicated, peak stress values are increase by ~18%, as one can expect higher values for higher CPT, based on previous the exercise, since the thick plies can be assumed to be equivalent to two thin plies. | As was previously described, main interlaminar stresses are located where 90° plies are. See Figure 9. Also, it can be noticed that as the ply thickness is duplicated, peak stress values are increase by ~18%, as one can expect higher values for higher CPT, based on previous the exercise, since the thick plies can be assumed to be equivalent to two thin plies. | ||

| Line 149: | Line 120: | ||

Test case show that increasing the CPT tends to slightly increase the free-edge effect. This can be related with the fact that for thick plies, the 90° plies concentrate the interlaminar stresses, leading to micro-cracks earlier than thin plies, where the 90° plies are spread across the thickness. | Test case show that increasing the CPT tends to slightly increase the free-edge effect. This can be related with the fact that for thick plies, the 90° plies concentrate the interlaminar stresses, leading to micro-cracks earlier than thin plies, where the 90° plies are spread across the thickness. | ||

| − | == | + | ==6. Failure criteria== |

In order to predict the failure of the laminate associated with the free edge effect a failure criteria is needed. There are 2 main families of procedures: | In order to predict the failure of the laminate associated with the free edge effect a failure criteria is needed. There are 2 main families of procedures: | ||

| Line 170: | Line 141: | ||

It is important to notice that for any method used to predict the failure, the main challenge is to decide where to evaluate the stress results. As it was described in the previous chapter, taking maximum values at the edge can lead to inaccurate results that do not represent the real state of the laminates. In that respect some authors suggested getting an average value to avoid choosing a peak value, see [9]. Also it seems that some sort of process needs to be added to select the interlaminar stress per ply, where not only peak or average value of the ply is selected but also the adjacent plies state is considered, as it seems to have an impact on the associated the failure mode. | It is important to notice that for any method used to predict the failure, the main challenge is to decide where to evaluate the stress results. As it was described in the previous chapter, taking maximum values at the edge can lead to inaccurate results that do not represent the real state of the laminates. In that respect some authors suggested getting an average value to avoid choosing a peak value, see [9]. Also it seems that some sort of process needs to be added to select the interlaminar stress per ply, where not only peak or average value of the ply is selected but also the adjacent plies state is considered, as it seems to have an impact on the associated the failure mode. | ||

| − | == | + | ==7. Conclusions and future work== |

As it was shown in the previous chapters, the proposed stress method to obtain interlaminar stress provides a robust solution compared with previous works, allowing to study different staking sequences and configurations. | As it was shown in the previous chapters, the proposed stress method to obtain interlaminar stress provides a robust solution compared with previous works, allowing to study different staking sequences and configurations. | ||

Latest revision as of 13:50, 16 December 2024

1. Introduction

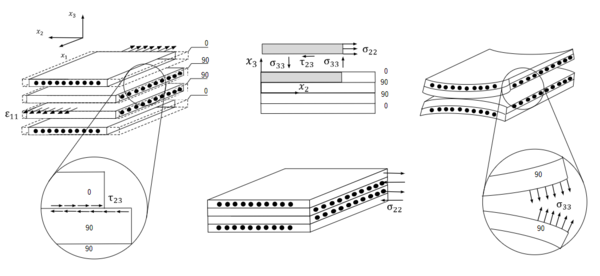

Free-edge effect is a stress concentration phenomenon that appears in the discontinuities of composite materials, such as edges, holes or corners. As it can be shown in the following example, see Figure 1, if we assume a stacking sequence such as [0/90/90/0], where the different layers are not bonded together, but just stacked, one on top of the other, if we apply to the stack a certain load in the direction, every ply suffers a shrink in the transverse direction , due to Poisson’s effect.

As the plies are not bonded in this example, every ply will shrink individually, based on the stiffness in the and direction, providing discontinuities in the displacements as it can be seen in the Figure 1. In real structures those plies are bonded together so stiffness difference between each orientation derive in an interlaminar stress resultant, as the displacements have to be the same to fulfill the boundary conditions and strain continuity.

2. State of the art

As it is described in detail in the paper of C Mittelstedt and W Becker, see [2] , there are different ways to solve the edge effect problem. Classical laminate analysis cannot be used to capture the interlaminar stresses in a flat panel and the 3D constitutive equations for an orthotropic composite material lead to a complex set of differential equations that have not been solved yet. All the available solutions are based on some sort of simplifications that allow to obtain a solution close to the real problem. Based on the nature of the solution, methods can be separated in two different main groups:

- Closed-form solution: In this group there are all the analytical methods that, based on some simplifications, obtain the interlaminar stresses, like the work of Puppo and Evensen, see [3] or Pagano, mixing Mindlin laminate theory and finite element models . Most of the methods of this group provide a fast an accurate solution but it fails to cover a wide range of use cases. For instance, they are usually limited to the stacking sequences tested, as they are mainly intended for research purpose.

- Finite Element models: These model are well-known to solve solid mechanical problems and are able to predict free-edge effect with the proper element formulation and mesh refinement, so most of the works are focused on high order elements and meshing convergence strategy, see Vidal [5]. Even if those methods can cover a wide range of stacking and loads, it requires a high amount of effort to set up the model, reducing the applicability for an industrial solution to be used for trade-offs and/or optimization.

In this document, an analytical method that solves the limitations previously explained, is selected and integrated in a tool called ESTOPA (Edge-effect STress On Plain strength Analysis). It tries to cover most of the needs for an industrial tool: robustness, accuracy and besides, it can be used for a wide range of laminates, materials and load combination.

3. Method description

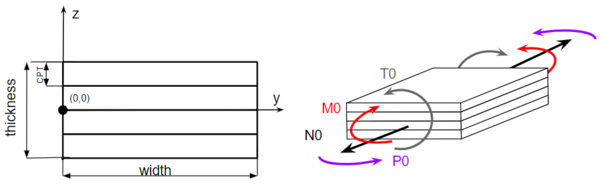

The analytical modelling of the free-edge effects is analyzed in a flat laminate where the main load direction is defined as the X-coordinate, the width direction as the Y-coordinate and the through-the-thickness direction as the Z-coordinate, as it is shown in Figure 2:

The development of the model is based on the higher-order moments modelling used in the PhD thesis of González-Cantero [6] for the modelling of the interlaminar stresses in curved laminates. This model is based on a 2D approach which allows the reduction of the complexity of the equations to be solved in an efficient way by numerical procedures. Hence, to extend it to other use-cases like the free-edge effect, it requires a reduction of the model to a 2D problem. The easiest assumption in the free-edge problem to be converted in a 2D problem is the suppression of the X-axis from the problem by assuming that the stresses and strains are depending only on the Y and Z directions, and constant in the X direction.

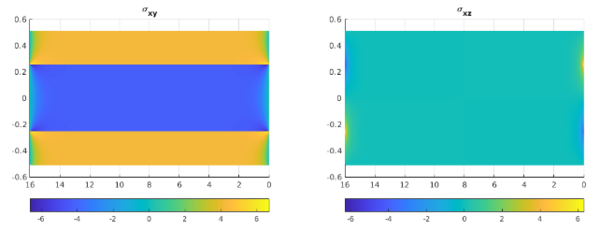

This model allows analysis of any stacking sequence, defined by its ply thickness and orientation. Different set of loads can be applied: axial load (N0), moment in xy-axis (P0), flexural moment in xz-axis (M0) and torsion in zy-axis (T0). The input flexibility is a great competitive advantage compared to other closed-form solutions, as they are mainly intended for research purpose. Outputs provided by the method are a set of 2D maps of all the stress components, together with the strain and displacements. See Figure 3:

4. Validation process

This method is useful for generating interlaminar stresses associated with the free edge effect. However, it's important to note that the method is based on certain assumptions and simplifications. Therefore, to ensure the robustness and accuracy of the solutions obtained with this method, a validation exercise had to be performed.

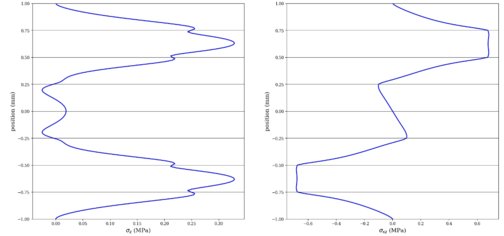

First, we checked the in-plane stresses that can be obtained using Classical Laminate Analysis (CLA) under 2D assumptions. Once the in-plane stresses were validated, we reviewed the interlaminar stresses. The literature provides a wide range of test cases that can be used to compare our results. Although different methods may have been applied to obtain these solutions, the underlying physics and results remain the same, see Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Additionally, Detail Finite Element Models were used to check the interlaminar stresses, while keeping in mind the limitations of this method, which can only yield quantitative results. Overall, this method has great potential to provide valuable insights into the behavior of composite materials and it converge into solutions previously validated. These evidences allow to trust the results and to use the tool in use cases not studied before in the bibliography.

5. Method Results

In this section the effect of the stacking sequence and ply thickness will be studied. As this effect is generated due to the stiffness difference between two adjacent plies, ply orientation in the stacking will drastically influence the interlaminar stresses. All the results values displayed are normalized to facilitate the comparison between cases.

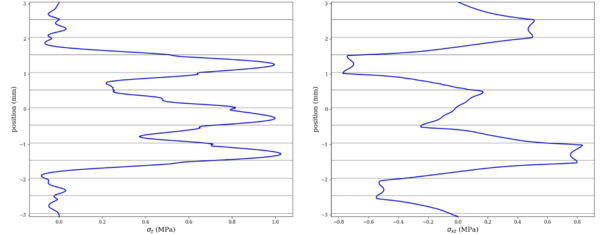

In this basic example a quasi-isotropic symmetrical laminate composed by 45°, -45°, 0° and 90° plies, can lead to different interlaminar values. First the following stacking will be studied: [45/ -45/ 0/ 90]s. This laminate concentrates two 90° plies at the center of the stacking, surrounded by 0° plies. As it can be shown in Figure 6, this generates an interlaminar σz peak at the 90° plies location, whereas the interlaminar shear σxz lies mainly in the 45/-45 package.

If the 90° plies are relocated around the 45° plies: [45/ 90/-45/ 0]s, two effects can be observed: in one hand interlaminar σz peaks are now located where the 90° plies are, reducing the interlaminar stress peak ~65%. Also, by separating the 45° plies, the interlaminar shear stress is spread over the stacking See Figure 7:

As it can be noticed, there are two main factors in the generation of interlaminar stresses: 90° plies cause the σz peak, especially when those are together and surrounded by 0° plies. Those out-of-plane stresses are usually of greater magnitude than the interlaminar shear stresses, but the latter cannot be neglected, especially the ones generated by the plies at 45°.

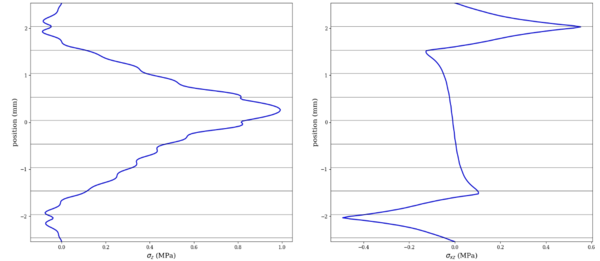

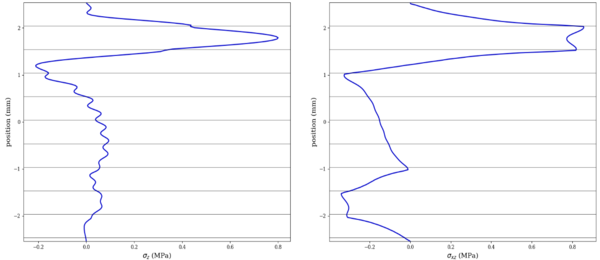

In the following exercise two stacking sequence are studied. The first stacking, [45/-45/0/0/90/0/0/0/-45/45] , based on the conclusions of the previous exercise, is intended to be prone to free-edge effect, as the 90° ply is strategically situated in the middle of the stacking, while the second laminate, [45/90/-45/0/0/0/0/-45/0/45], is intended to mitigate those effects, as now that 90° ply is outside the middle plane and covered by 45° plies. Result can be show in Figure 8:

As it was expected maximum stress values can be found on the 90° plies, again, comparing results it can been found that placing 90° plies between 45° plies may lead to some significance thought-the-thickness stress reduction ~20%.

Nevertheless, analyzing only max values can lead to wrong interpretation of the real phenomena as the stresses depicted here are the value obtain at y =0.1mm of the edge, but they are related to a stress concentration effect and decrease far from the edges. As it can be shown in the first laminate, the amount of plies that are suffering a positive σz (tensile) covers almost 6 plies, reaching its peak at the 90 ply, whereas in the second stacking, only the 90° ply is under interlaminar stresses and it decreases outside this ply. This fact it crucial in order to understand the area of the stacking that is affected from free-edge effect Ply thickness effect.

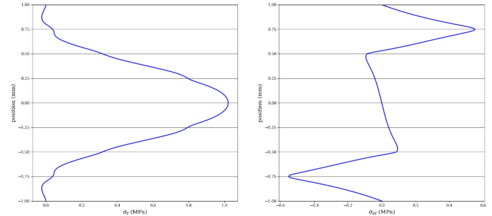

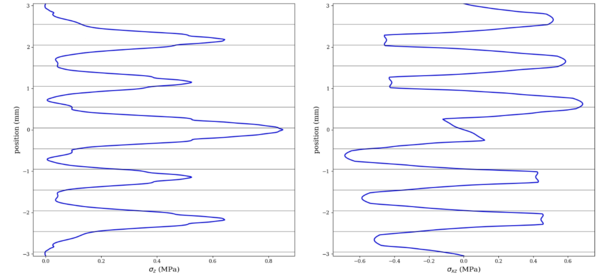

Other interesting exercise can be performed when the ply thickness is modified: in this example two stacking with the same thickness and almost the same mechanical properties are compared. The main difference is in the ply thickness, the first stacking sequence has a cured ply thickness (CPT) of 0.25mm and a staking sequence: [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90], whereas second stacking is [45/0/-45/90/45/0/-45/90]s, of CPT 0.5 mm.

As was previously described, main interlaminar stresses are located where 90° plies are. See Figure 9. Also, it can be noticed that as the ply thickness is duplicated, peak stress values are increase by ~18%, as one can expect higher values for higher CPT, based on previous the exercise, since the thick plies can be assumed to be equivalent to two thin plies.

Test case show that increasing the CPT tends to slightly increase the free-edge effect. This can be related with the fact that for thick plies, the 90° plies concentrate the interlaminar stresses, leading to micro-cracks earlier than thin plies, where the 90° plies are spread across the thickness.

6. Failure criteria

In order to predict the failure of the laminate associated with the free edge effect a failure criteria is needed. There are 2 main families of procedures:

- Solid mechanics: where the main driver for the failure is based on the interlaminar stresses, in this family the work of Kim & Soni can be found [9], where the 3D state of the material is used together with thought-the-thickness allowables, to obtain a reserve factor (RF), see (1).

|

|

(1) |

- Fracture mechanics: these are calculated based on the stress intensity factors or the strain energy release rates, in this family the Energy power law formula can be found where the three different fracture mode are used, see O’Brien [10] .

It is important to notice that for any method used to predict the failure, the main challenge is to decide where to evaluate the stress results. As it was described in the previous chapter, taking maximum values at the edge can lead to inaccurate results that do not represent the real state of the laminates. In that respect some authors suggested getting an average value to avoid choosing a peak value, see [9]. Also it seems that some sort of process needs to be added to select the interlaminar stress per ply, where not only peak or average value of the ply is selected but also the adjacent plies state is considered, as it seems to have an impact on the associated the failure mode.

7. Conclusions and future work

As it was shown in the previous chapters, the proposed stress method to obtain interlaminar stress provides a robust solution compared with previous works, allowing to study different staking sequences and configurations.

The effect of the stacking sequence is studied in two different cases where it can be seen that 90° plies are the main accumulators of interlaminar stress and their position in the stack influences drastically the overall state of the σz values through the thickness, whereas 45 plies are the main accumulators of interlaminar shear stresses. Ply thickness affects the free-edge effect as it accumulates the interlaminar stress in less 90 plies for the same thickness, compare with thin plies.

A robust Failure criteria needs to be generated based on those facts in order to predict the premature failure of the structure, not only taking into account the peak values per ply but also the complex load state that the real structure may have. Next steps will require to combining this failure mode with the rest of well-known failure modes already use to analyze composite laminates.

Bibliography

| [1] | NJ Pagano and R Byron Pipes. Some observations on the interlaminar strength of composite laminates. International journal of Mechanical Sciences, 15(8):679-688, 1973. |

| [2] | C Mittelstedt and W Becker. Free-edge Effect in composite laminates. Applied Mechanics Reviews, 60(5):217-245, 2007. |

| [3]

|

AH Puppo and HA Evensen. Interlaminar shear in laminated composites under generalized plane stress. Journal of composite materials, 4(2):204-220, 1970 |

| [4] | NJ Pagano. On the calculation of interlaminar normal stress in composite laminate. Journal of Composite Materials, 8(1):65-81, 1974 |

| [5] | P Vidal, L Gallimard, and O Polit. Assessment of variable separation for finite element modeling of free edge effect for composite plates. Composite Structures, 123:19-29, 2015 |

| [6] | González Cantero, Juan Manuel. Study of the unfolding failure of curved composite laminates. 2017. |

| [7] | C Mittelstedt and W Becker. The Pipes-pagano-problem revisited: elastic fields in boundary layers of plane laminated specimens under combined thermomechanical load. Composite structures, 80(3):373-395, 2007. |

| [8] | Dhanesh, N., Kapuria, S., & Achary, G. G. S. Accurate prediction of three-dimensional free edge stress field in composite laminates using mixed-field multiterm extended Kantorovich method. Acta Mechanica, 228, 2895-2919. 2017. |

| [9] | RY Kim and SR Soni. Experimental and analytical studies of the onset delamination in laminated composites. Journal of composite materials, 18(1):70-80, 1984. |

| [10]

|

O’Brien, T. K. “Characterization of delamination onset and growth in a composite laminate”. Damage in Composite Materials, ASTM STP 775, K. L. Reifsnider, American Society for Testing and Materials, pag. 140-167. 1982. |

Document information

Published on 29/04/25

Accepted on 15/12/24

Submitted on 30/05/23

Volume 08 - COMUNICACIONES MATCOMP21 (2022) Y MATCOMP23 (2023), Issue Núm. 8 - Fabricación y Aplicaciones Industriales - Materiales y Estructuras - Modelos Numéricos, 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.23967/r.matcomp.2025.08.14

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?