Summary

Introduction

Using laparoscopic methods for incarcerated scrotal hernias is controversial because of the perceived technical difficulties in treating such hernias. Herein, we present our experience with laparoscopic repair of such hernias.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review was undertaken to evaluate our experience with laparoscopic transabdominal approach and its modification for incarcerated hernias over a 3-year period. Two laparoscopic techniques were used for the repair of such hernias. The first technique, an exploratory laparoscopy, was performed to inspect the content of the hernia. This was followed by gentle retraction of the hernial content into the abdominal cavity and performing a standard transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) repair. If the hernia was not reducible, then a second technique involving a paramedian scrotal incision was performed. The sac was isolated, opened, and its contents were examined. If the bowel was encountered, it was reduced into the peritoneal cavity. However, if it was the omentum, it was excised. Following ligation of the scrotal sac and re-insufflation of the abdomen, a standard TAPP ensued.

Results

A total of 20 male patients with incarcerated scrotal hernia underwent laparoscopic TAPP repair (mean age: 48 years). Six had scrotal incision. Surgical site or mesh infection was not observed in any of the cases. Likewise, no recurrence after a mean follow-up of 22 months was encountered.

Conclusion

Using the above modifications, we were able to perform laparoscopic repair of large incarcerated scrotal hernias, which previously would have been treated with an open procedure.

Keywords

incarcerated;laparoscopy;scrotal hernia;scrotal incision;transabdominal preperitoneal repair

1. Introduction

Scrotal hernia is defined as the inguinal hernia that has passed into the scrotum. It is termed incarcerated when it cannot be reduced into the abdomen. It has been estimated that the probability of inguinal hernia incarceration varies from 0.29% to 2.9%1 and incarcerated hernias are the second most common cause of small bowel obstructions.2 Until now, surgical management of incarcerated groin hernias has been by open surgery, with laparoscopic approach considered as relatively contraindicated. The main controversies surrounding the optimal treatment of incarcerated scrotal hernias using laparoscopic procedures are issues of technical difficulties in the dissection of the large hernia sac, difficulty in the reduction of scrotal hernia content through a narrowed internal inguinal ring, and the increased incidence of seroma or hematoma. In this article, we present our experience with laparoscopic repair of such hernias and focus on the technique of transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) approach and its modification.

2. Materials and methods

Laparoscopic TAPP hernia repair has been performed in our department since 2007. Our approach for all reducible groin hernias has been laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal (TEP) approach and we reserve the TAPP approach for incarcerated groin hernias (Fig. 1) except in our early learning experience with the TEP approach, where we encountered loss of extraperitoneal space and had to perform TAPP in order to complete the surgery.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Large incarcerated scrotal hernia—anterior and lateral views. |

Between September 2007 and October 2010, over a period of 38 months, 20 consecutive patients with chronic incarcerated scrotal hernias who underwent TAPP at the Department of Surgery of the Sarawak General Hospital were retrospectively enrolled to the study. Data on patient demographics, types of hernia, duration of surgery, intraoperative and postoperative complications, hospital stay, and recurrence were collected.

2.1. Surgical technique

The patient was placed supine with the arms by the side. The surgeon stood on the contralateral side of the hernia while the camera surgeon stood ipsilaterally. The scrub nurse stood next to the surgeon along with the laparoscopic trolley. The monitor was placed at the foot end of the patient.

An infraumbilical incision, or rarely a supraumbilical incision for lowly placed umbilicus, was made using the open access technique, followed by insertion of Hasson trocar with the blunt obturator. Two working 5-mm trocars were then inserted under vision at the right and left pararectus regions. The patient was then tilted 10° head down to allow the bowel loops to fall away from the groin region.

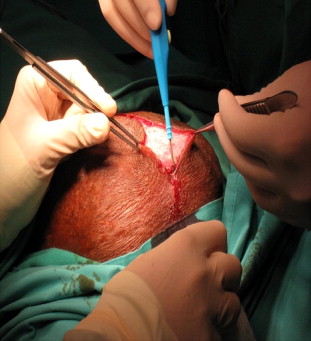

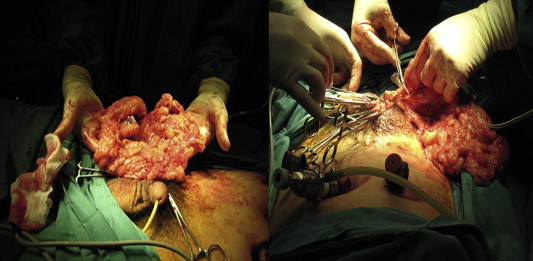

We used two laparoscopic techniques to treat such hernias. In the first technique, we performed a gentle retraction of the hernia content into the abdominal cavity after the initial exploratory laparoscopy to inspect the content of the hernia. Simultaneous manual compression from the scrotum was performed to aid in reduction. If it remained irreducible, we proceeded with a second technique that involved a paramedian scrotal incision (Fig. 2). The sac was isolated, opened, and its sac content was examined. If the bowel was encountered, it was reduced into the peritoneal cavity. However, if it was the omentum, it was excised (Fig. 3). The sac was then ligated with polyglactin 910 2/0 before re-insufflation of the abdomen (Fig. 4).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Paramedian scrotal incision (2–2.5 cm). |

|

|

|

Figure 3. Excision of the omentum was performed when encountered upon opening of the scrotal sac. |

|

|

|

Figure 4. Ligation of the sac before re-insufflation of the abdomen. |

A standard TAPP repair entailed a peritoneal incision made from the level of the anterior superior iliac spine, extending 2 cm above the defect and curving up laterally to the medial umbilical ligament in a hockey-stick manner.

Medial and lateral dissections of the preperitoneal space were performed using a two-handed technique. A Maryland forceps or scissor was used to dissect the preperitoneal fatty tissue from the abdominal muscle, and a grasper was used to maintain traction on the peritoneal flap. Medial dissection was carried out by identifying important anatomical structures such as inferior epigastric vessels, pubic symphysis, pubic rami, and Coopers ligament while lateral dissection exposed the psoas muscle. The bridging vessels in the preperitoneal space were coagulated immediately with monopolar cautery to maintain a clear operative field. In addition, care was taken during dissection beneath the iliopubic tract to avoid injury to iliac vessels (triangle of doom) and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (triangle of pain).

Next, we used hand-over-hand technique, pulling the sac on the cord medially, while sweeping the cord structures laterally. The dissection was continued distally with the hernia sac divided beyond the internal ring within the canal, leaving the distal end of the sac in situ.

Parietalization of the peritoneum from the vas deferens and gonadal vessels was carried out to ensure free placement of the mesh without folding. We then rolled a 15 × 10-cm2 sized prolene mesh and tied it with a suture to keep it in a rolled position before introducing it through a 10-mm trocar into the peritoneal cavity. Once the mesh was placed in the dissected space, the stitch was removed to unroll the mesh. We then fixed the mesh to the Coopers ligament medially and inferior surface of rectus muscle laterally with two titanium staples. The peritoneal flap was closed either by continuous suturing using 2–0 vicryl or with titanium staples.

Foleys catheter was routinely inserted intraoperatively. For those cases involving scrotal incision, Redivac drain (Primed Germany) was inserted into the scrotum, inside the hernia sac. It was later attached to an evacuated vacuum bottle providing suction and generally removed after 48–72 hours or earlier once drainage had stopped or become less than 30 mL/day. Postoperatively, all patients were recommended to wear well-fitting underwear for the purpose of scrotal decompression.

3. Results

In this study, 20 patients underwent TAPP repairs. All the patients were men with a mean age of 48 years (range: 23–78). All had primary hernia. Of these, nine (45%) had hernia on the right side and all were indirect hernias.

The mean operating time was 143.7 minutes (range: 75–240). The operating time was longer in the first 10 patients with a mean time of 164 minutes (range: 90–240) compared with the last 10 patients with a mean time of 123.5 minutes (range: 75–200) as we gained expertise and experience in such repair.

Three patients had intraoperative complications. One patient had testicular artery injury during mobilization of the sac from the cord structure and the artery was clipped. However, he made an uneventful recovery without an adverse outcome of testicular atrophy during the follow-up review in the clinic. Two patients had bowel serosal injury (small bowel and sigmoid colon) during mobilization from the internal inguinal ring. Both injuries were repaired intracorporeally using suture polyglactin 910 3/0 (interrupted closure). None of the cases were converted to open technique and no bowel resection was necessary because the incarcerated bowels were always capable of being reduced. Six patients required scrotal incision to achieve mobilization and reduction of hernia content and three of them had postoperative scrotal hematoma that resolved spontaneously.

The mean postoperative stay was 1.9 days (range: 1–5). None of the patients had mesh or surgical-site infection. At the time of writing, no recurrences were observed after a mean follow-up period of 22 months (range: 9–46).

4. Discussion

Laparoscopic approach for inguinal hernia has distinct advantages over open techniques, in terms of reduced acute and chronic postoperative pain, shorter convalescence, and early return to work or activities.3; 4 ; 5 Therefore, it has a beneficial role in bilateral, recurrent, and primary hernias. However, its role in incarcerated scrotal hernias is still debatable, largely attributable to the fact that it is technically difficult to repair such hernias, which require a high level of expertise and experience on the part of the surgeon, irrespective of the applied surgical technique.

There are several studies that support the safety and effectiveness of the laparoscopic TEP or TAPP approach for the treatment of acute or chronic incarcerated inguinal hernia.6; 7; 8; 9 ; 10 Many innovative laparoscopic techniques have been described as part of the modifications to TEP and TAPP approaches. These include exploratory laparoscopy with reduction, and when necessary, resection of the hernia sac contents, followed by TEP repair.11 ; 12 The division of the internal ring for the reduction of the incarcerated hernia is also advocated.6; 7; 8; 10 ; 13 An author suggested the division of the inferior epigastric vessels to facilitate a releasing incision over the transversalis fascia in the TEP approach for large indirect scrotal hernia.14 Another author described a 2.5-cm groin incision for extracting the omentum, which had been “predetached” laparoscopically at the deep ring.9

Although many techniques have been described in association with reduction of scrotal hernias, none of the literature we have come across describes the scrotal incision technique. With transabdominal approach, we were able to pull the contents of incarcerated hernia with forceps and return them to the abdominal cavity in 14 patients. External pressure was applied outside the scrotum toward the internal inguinal ring in some of them. However, in six patients, there was some concern about the inadvertent injury to the incarcerated bowel while pulling as there appeared to be extra resistance to reduction. In such circumstances, we desufflated the abdomen while leaving the trocars on the abdomen and proceeded to paramedian ipsilateral scrotal incision. In majority of the cases, we found that the hernia contents were adherent to the scrotal end of the sac. By opening the sac at scrotal end and releasing the adhesions using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, we were able to reduce some of the difficult large scrotal hernias through the internal ring either by pushing from the scrotal end or pulling from the abdomen.

We feel that the TAPP approach is more favorable than the TEP approach in incarcerated scrotal hernia as there is a particular problem with extraperitoneal space. The space is always limited even when the incarcerated hernia has been reduced by scrotal incision, as the sac is often very large and requires extensive dissection from the cord structures. We learned from our experiences in the TEP approach for reducible groin hernias that the dissection of large sac from the cord structures in a limited space is often difficult and frustrating. When the sac is torn during manipulation or has been divided, there is an inevitable escape of CO2 into abdominal cavity, leading to collapse of the working space. Moreover, TAPP facilitates the inspection of contralateral hernia orifices and detection of unsuspected hernia,6 ; 13 which are not possible with the TEP approach. This allows the repair of contralateral hernia in the same setting.

Another advantage of TAPP over open and TEP approaches is in the setting of acute incarceration where it allows for assessing the viability of incarcerated bowel at reduction and sufficient time to observe the return of color and peristalsis of bowels if viability is initially doubtful.7; 8 ; 13 Unlike open technique where the surgeons have a few minutes to make a decision on bowel resection, transabdominal approach allows the reassessment of the viability of bowels at the end of the procedure, and thereby, avoiding unnecessary bowel resection.7; 8 ; 13

The role of a Foley catheter intraoperatively is controversial.6; 10 ; 14 Although we did not routinely use a Foley catheter for reducible inguinal hernia, we believe that the placement of a Foley catheter intraoperatively is important for incarcerated scrotal hernia. The time taken for repair of incarcerated scrotal hernia is longer compared with reducible inguinal hernias. In addition, the bladder may be contained within the hernia, posing a risk of injury during dissection.

There were three cases of scrotal hematoma in the scrotal incision group. One possible explanation for this problem is the distinctly larger hernia sac in this group of patients. However, it was self-limiting without undue symptoms for the patients. If it became bothersome, needle aspiration would generally suffice.

In conclusion, the surgical treatment of incarcerated scrotal hernias is often difficult irrespective of open or endoscopic approach. Our study showed that laparoscopic approach with its modified technique is safe and feasible in patients with incarcerated scrotal hernias. In addition, it encompassed the advantages of endoscopic procedures.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Director General of Health, Malaysia, for granting permission to publish this paper.

References

- 1 N.C. Gallegos, J. Dawson, M. Jarvis, M. Hobsley; Risk of strangulation in groin hernias; Br J Surg, 78 (1991), pp. 1171–1173

- 2 B. Kulah, I.H. Kulacoglu, M.T. Oruc, et al.; Presentation and outcome of incarcerated external hernias in adults; Am J Surg, 181 (2001), pp. 101–104

- 3 L. Neumayer, A. Giobbie-Hurder, O. Jonasson, et al.; Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia; N Engl J Med, 350 (2004), pp. 1819–1827

- 4 K. McCormack, N.W. Scott, P.M. Go, et al.; Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair; Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2003) CD001785

- 5 M. Hallén, A. Bergenfelz, J. Westerdahl; Laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair versus open mesh repair: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial; Surgery, 143 (2008), pp. 313–317

- 6 B.J. Leibl, C.G. Schmedt, K. Kraft, M. Ulrich, R. Bittner; Scrotal hernias: a contraindication for an endoscopic procedure? Results of a single-institution experience in transabdominal preperitoneal repair; Surg Endosc, 14 (2000), pp. 289–292

- 7 T. Ishihara, K. Kubota, N. Eda, S. Ishibashi, Y. Haraguchi; Laparoscopic approach to incarcerated inguinal hernia; Surg Endosc, 10 (1996), pp. 1111–1113

- 8 G.L. Legnani, M. Rasini, S. Pastori, D. Sarli; Laparoscopic trans-peritoneal hernioplasty (TAPP) for the acute management of strangulated inguino-crural hernias: a report of nine cases; Hernia, 12 (2008), pp. 185–188

- 9 C. Palanivelu, M. Rangarajan, S.J. John; Modified technique of laparoscopic intraperitoneal hernioplasty for irreducible scrotal hernias (omentoceles): how to remove the hernial contents; World J Surg, 31 (2007), pp. 1889–1891 discussion 1892–1893

- 10 C. Rebuffat, A. Galli, M.S. Scalambra, F. Balsamo; Laparoscopic repair of strangulated hernias; Surg Endosc, 20 (2006), pp. 131–134

- 11 A. Hoffman, E. Leshem, O. Zmora, et al.; The combined laparoscopic approach for the treatment of incarcerated inguinal hernia; Surg Endosc, 24 (2010), pp. 1815–1818

- 12 C. Tamme, H. Scheidbach, C. Hampe, C. Schneider, F. Köckerling; Totally extraperitoneal endoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP); Surg Endosc, 17 (2003), pp. 190–195

- 13 R.B. Jagad, J. Shah, G.R. Patel; The laparoscopic transperitoneal approach for irreducible inguinal hernias: perioperative outcome in four patients; J Minim Access Surg, 5 (2009), pp. 31–34

- 14 G.S. Ferzli, T. Kiel; The role of the endoscopic extraperitoneal approach in large inguinal scrotal hernias; Surg Endosc, 11 (1997), pp. 299–302

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?