Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

This paper presents design thinking as an alternative approach to conduct research on collaborative learning with technology. The underlying premise of the paper is the need to adopt human-centered design principles in research and design of computer-supported collaborative tools. Two research results are described in order to discuss the possibilities and challenges of applying design methods for designing and researching collaborative knowledge building tools. The paper begins by defining collaborative learning with new technologies as a wicked problem that can be approached by adopting a design mindset. Design thinking and particularly research-based design relies on a shared, social construction of understanding with the people who will later use the tools. The key phases in researchbased design (contextual inquiry, participatory design, product design and software as hypothesis) are described and exemplified through the presentation of two research results. The two prototypes presented are the fourth version of the Future Learning Environment (Fle4), a software tool for collaborative knowledge building and Square1, a set of hardware and software for self-organized learning environments. Both cases contribute to the discussion about the role of artifacts as research outcomes. Through these cases, we claim that design thinking is a meaningful ap proach in CSCL research.

1. Introduction

Wicked problems is a term used to describe problems that are difficult to solve because they are incomplete, requirements are constantly changing, and there are various interests related to them. Solutions to wicked problems often require that many people are willing to think differently on the issue and change their behavior. Wicked problems are common in economics, social issues, public planning, and politics. Characteristic of wicked problems is that solving part of the problem often causes other problems. To wicked problems there are no true or false answers, but rather good or bad solutions (Rittel & Webber, 1973).

Teaching, learning with technology in general, and computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) in particular can be seen as a wicked problem (Mishra & Koehler, 2008; Leinonen 2010). Many problems related to collaborative learning and computers are incomplete and contradictory. In CSCL practices, there are many actors with various complex interdependencies, including teachers, learners, and the interconnected computers. According to Mishra & Koehler (2008), researchers working in the field should recognize the complexity of the situations in an educational context with learners, teachers and technology. In this sense, there is a growing demand for collaboration between researchers, designers, teachers, and learners during the process of designing technologies for learning (Dillenbourg & al., 2009; Bonsignore & al., 2013).

Design thinking has been identified as a meaningful approach to tackle wicked problems (Buchanan, 1992). For instance, according to Nelson and Stolterman (2003), design does not aim to solve a problem with an ultimate answer, but to create a positive addition to the present state of affairs. This way, design differs significantly from ordinary problem solving. Designers do not see the world in such a way that somewhere there is a perfect design they should discover; rather they aim to contribute to the current state with their design. So, design is an exploratory activity where mistakes are made and then fixed. Poetically, one may say that design is navigation without a clear map, relying only on current context and the information gathered from it.

The epistemological basis of design thinking is that most parts of the world we are living in are changeable, something we as humans can have an impact on. In design thinking, people are seen as actors who can make a difference. People can design relevant solutions that will have a positive impact. This way, design thinking is a mindset characterized by being human-centered, social, responsible, optimistic, and experimental.

In this article, we present design thinking as an alternative approach for conducting research in the field of CSCL. To demonstrate the results of design thinking-driven research in CSCL, we present two artifacts produced with the approach. We start with a general discussion about design and design thinking. We continue with a description of our methodological approach. We then present two results from our research in the field of CSCL, which we got by using a strong design-thinking approach. The results are applications designed for collaborative knowledge building (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2003) and collaborative learning in a self-organized learning environment (Mitra, 2013).

2. Design thinking in context

Design research often starts with observation, reflection, and questioning. A questioning design researcher is especially interested in everyday life practices. He or she may realize that many things that are considered to be normal, natural, and unchangeable are actually problematic. A questioning design researcher is interested in reflecting upon his or her research’s significance for human life in general and on different human practices in an everyday context. People involved in the research are seen as part of the same human reality. In the research, they are not objects of the research, but rather subjects in the research. A questioning design researcher does not see that his or her job would be to produce neutral facts or be neutral at all. Therefore, consideration and discussions on value and their impact on the research are a large part of the research. An inquiry by a questioning design researcher holds an ethical meaning as a valuator of human existence and behavior (Varto, 2009; Leinonen, 2010).

In questioning design research, the focus is not only on aesthetics and usability, much broader and fundamental issues are taken into consideration. For instance, Hyysalo (2009) categorizes design on five different levels. To illustrate the different levels of design, we may use the design of a mobile phone’s power button as an example.

1) On the first level, design is about details. For instance, design of a mobile phone power button’s physical shape, icon, and color is a design of details.

2) On the second level, there is the user interface design. A decision that one should hold the power button down for a second and after that the phone will give feedback with a vibration telling that it is starting up is one example of user interface design.

3) On the third level of design, the interest is on systems. The logic that the phone will keep its setting although it is turned off is design of the entire software system running on the phone.

4) The fourth level in design includes social issues. For instance, the functionality included in a mobile phone’s power button making it possible to put it in silent mode or in meeting mode is a decision that pays attention to the social contexts in which the phone is used.

5) The fifth level in design takes into consideration broad societal implications. The decision that switching off with the power button will make the phone impossible to track can be a decision made to protect the user’s privacy.

Decisions made on the different levels of design cannot be made separately. They are interconnected and influence each other. The complexity of design requires research, the ability to see both the whole and the details, and the skill to analyze them.

Design may provide people an idea of new ways of doing things and different perspectives and interpretations about the reality they are living in. This way, design can be a way to confront complexity and respond to people’s intentions to deliberately change the world (Nelson & Stolterman, 2003). When including interpretations of complexity, design can never be a neutral activity. Behind design, we may find value-laden, even ideological, ideas and principles. As Bruce (1996) highlights, it is not only that the meanings of these artifacts are socially constructed, but the physical design and social practices around them are socially constructed. Understanding design as socially constructed and results of design as something that will have a real impact on the socially constructed reality people are living in, asks for responsibility and accountability from the designers and the people taking part in the design.

The Scandinavian tradition of participatory design is one of the earliest models of design thinking. In participatory design, the people who are expected to be the beneficiaries of a design are invited to take part in the process from the early stages. By involving people in the process, it is expected that the results as a whole will be better than if done without them. For instance, Ehn and Kyng (1987), who have done design research related to computers in workplaces, have noticed that the design of a computer tool is not just a design of a tool, but it also has consequences on the work processes and the entire workplace. The adoption of collaborative learning in education presents similar challenges, since it requires rethinking the classroom culture as well as the curricular goals and the institutional framework (Stahl, 2011). Therefore, recognizing people as the primary source of innovation is crucial in order to reach designs that will serve the needs of the people who will work, learn, or teach with the designed tools. This means that at the same time as the design of the tool, the community is asked to partly reconsider and redesign their current work processes.

First, design thinking, in the case of designing tools for CSCL, means that the design researchers will work simultaneously on all the different levels of design. Rather than enabling just collaboration, a successful collaborative learning environment creates the conditions for effective group interactions (Dillenbourg, 2009). When designing tools, design researchers must adopt a complex understanding of group interaction and consider the social implications of their work, but they also make decisions on the user experience, interface, and their details. Secondly, in the design of CSCL tools, we must be aware of the different interests among the different stakeholders. In the case of education, there are, for instance, different value bases, ideologies, and pedagogical approaches that are often hard to consolidate. The designers must stand for something and be transparent about the value-based decisions in the process. Thirdly, teachers and learners must have a voice in the design process, and the object of design should not only be the CSCL tool, but the entire learning process and practices of the school.

3. Methodological approach: Research and design interventions

To tackle the wicked problem of CSCL, we have used research-based design as a methodological approach (Leinonen & al., 2008; Leinonen, 2010). In research-based design, it is essential to see the results of the design –the artifacts– as primary outcomes and the main results of the activity. This way, the artifacts on their part are arguing the research results.

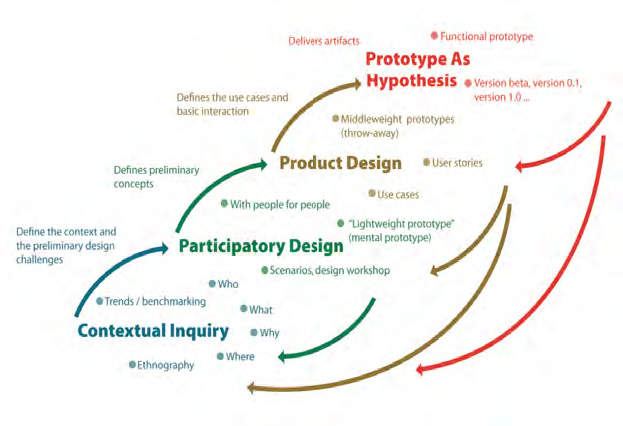

The research-based design process is a research praxis inspired by design theories (Ehn & Kyng, 1987; Schön, 1987; Nelson & Stolterman, 2003). It emphasizes creative solutions, playful experiments, and the building of prototypes. It encourages researchers and designers to try out various ideas and concepts. The research-based design process can be described as a continuous process of definition and redefinition of problems and design opportunities, as well as design and redesign of prototypes. Most of the activities take place in a close dialog with the community that is expected to use the tools designed. The process can be divided into four major phases, although they all happen concurrently and side-by-side (figure 1). At different times of the research, researchers are asked to put more effort into different phases. The continuous iteration, however, asks researchers to keep all the phases alive all the time.

In the first phase –the contextual inquiry– the focus is on the exploration of the socio-cultural context of the design. The aim is to understand the environment, situation, and culture where the design takes place. The results of the contextual inquiry are better understanding of the context by recognizing in it possible challenges and design opportunities. In this phase, design researchers use rapid ethnographic methods, such as participatory observation, note-taking, sketching, informal conversations, and interviews. At the same time as the field work, the design researchers are doing a focused review of the literature, benchmarking existing solutions, and analyzing trends in the area in order to develop insights into the design challenges.

In the second phase –participatory design– workshops with the stakeholders are conducted. The workshops are based on the results of the contextual inquiry. In small groups of 4-6, the results of the contextual inquiry are discussed and developed further. A common practice is to present the results as scenarios made by the design researchers containing challenges and design opportunities. In the workshop, the participants are invited to come up with design solutions to the challenges and to bring to the discussion new challenges and solutions. Later, the participatory design workshops are organized to discuss the early prototypes.

The results of the participatory design are analyzed in a design studio by the design researchers and used to create early prototypes that are then tested and validated again in participatory design sessions. By keeping a distance from the stakeholders, in the product design phase the design researchers will get a chance to analyze the results of the participatory design, categorize them, use specific design language related to implementation of the prototypes, and finally make design decisions.

Ultimately, the prototypes are developed to be functional on a level that they can be tested with real people in their everyday situations. The prototypes are still considered to be a hypothesis, prototypes as hypothesis, because they are expected to be part of the solutions for the challenges defined and redefined during the research. It remains to the stakeholders to decide whether they support the assertions made by the design researchers.

Research-based design is not to be confused with design-based research (Barab & Squire, 2004; The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003; Fallman, 2007; Leinonen & al., 2008). In research-based design, which builds on art and design tradition, the focus is on the artifacts, the end-results of the design. The way the artifacts are, the affordances and features they have or do not have, form an important part of the research argumentation. As such, research-based design as a methodological approach includes research, design, and design interventions that are all intertwined.

4. Results: FLE4 and Square1 prototypes

By using the design-thinking approach and research-based design process described in the earlier sections, we have designed and developed two prototypes of the CSCL tools: (1) the fourth version of the Future Learning Environment (Fle4), a web-based software program for collaborative knowledge building, and (2) Square1, a collection of learning devices designed for collaborative learning at school.

Fle4 and Square1 both rely on social constructivist learning and Lev Vygostky’s theory of the proximal development zone. The prototypes are designed to help and guide the learners’ social process of knowledge construction that is distributed among the people and their tools in use. The pedagogical foundation has had a great impact on the design of prototypes. For instance, prototypes are designed so that learners do not only construct knowledge but also have a role in the co-creation of their learning environment.

Fle4 and Square1 have been designed based on the latest research in CSCL, where researchers have emphasized the importance of engaging students and teachers in coordinated efforts to build new knowledge and to solve problems together (Dillenbourg, Baker, Blaye & O’Malley, 1996). Similarly to other environments such as CoVis1, CoNotes, Beldere2, and CLARE, research on the two prototypes has focused on building upon and testing the theories of collaborative production, knowledge building discourse, and scaffolding. In the following, we present the tools, Square1 and FLE4, and describe in more detail the design research in different phases of the research-based design process.

4.1. FLE4 – Future Learning Environment 4

Fle4 (Future Learning Environment 4) is a tool for knowledge building designed to work on the WordPress blog platform (http://fle4.aalto.fi/about). Fle4 is the latest iteration and version of the FLE research started in 1998. During the years, we have released four functional prototypes, FLE (1988-1999), Fle2 (2000-2001), Fle3 (2002), and Fle4 (2012). FLE was originally addressed to children, teachers, and parents in Finland. Later the research was continued in a European context. In the case of Fle3, the tool has been used in all the continents, and the user interface has been translated into more than 20 languages. Even today, Fle3 is used in some primary and secondary schools.

The challenge that motivated the original design of FLE was the observed lack of student-centered knowledge building activities in schools in Finland. Although these ideas were discussed among teachers and in teacher-training schools, the actual practices in classrooms were seen to be traditional and hard to change. Therefore, FLE was intended to support Progressive Inquiry learning (Hakkarainen, 2003), a learning model developed side-by-side with FLE. Progressive Inquiry is a way of learning where teachers and learners are engaged in sustaining continuous knowledge building across different school subjects. The idea is to imitate practices of knowledge-intensive work – a process that is common among scientific research groups.

Similarly to other tools focused on collaborative inquiry, FLE aims to facilitate higher-level understanding by asking learners to present questions, to generate explanations and theories for the phenomena under investigation (Bruner, 1996; Carey & Smith, 1995; Dunbar & Klahr, 1988; Perkins & al., 1995; Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1993; Schwartz, 1995). Engaging learners to formulate new questions and explanations is a key issue as learners are more used to find answers to pre-existing questions rather than posing new ones.

The hypothesis of the FLE prototypes was that a well-designed computer supported collaborative learning tool could drive the inclusion of more knowledge building activities in the classroom and therefore change the existing pedagogical practices in schools. As the first full prototype of the FLE, the Fle3 offered a digital space in which members of the learning community could find: 1) Web-tops for learners to collect and share information, 2) a Knowledge building tool for scaffolded online discussion with the aim of increasing the group’s level of knowledge and understanding about the topic under investigation, and a 3) jamming tool for the collaborative design of digital artifacts.

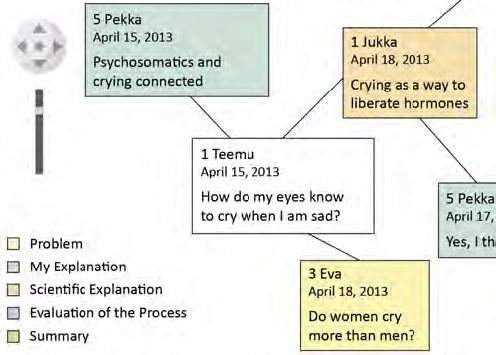

As the latest version, the Fle4 builds on the work carried out in the design of the Fle3. The FLe4 offers a tool for knowledge building that can be integrated and used with a blog service. When compared to the Fle3’s knowledge building tool, the Fle4 provides visual and zoom-able network views to the discourse (figure 2). This is expected to help learners keep track of the various activities in the knowledge building discourse as well as organize notes according to their importance. Fle4 also provides more advantaged ways to explore the knowledge building discourse by clustering notes according to authors and used knowledge types. Learners may also view the notes on a timeline.

In the design research of the different versions of FLE, the contextual inquiry of the research-based design process has been focusing on the practices of school learning and the possibilities to change some of them. By studying school children, teachers and parents were able to recognize a need to change the practice, although we also realized that it can be very hard and may take very long time. Another key observation deals with the changes happening in the whole knowledge infrastructure: the Internet connections and computers in schools were supposed to challenge traditional school learning, although at the same time, services such as the Learning Management Systems (LMS) provided for schools were relying on the traditional methods of teaching and learning. With the FLE, we wanted and still want to present an alternative approach to use computers and the Internet in school learning: more student-centered with a strong emphasis on collaborative work with knowledge.

As part of the design-based research process in the FLE research, we have conducted numerous participatory design sessions with teachers and schoolchildren in several European countries. In these, we have designed features with teachers and children and tested paper prototypes and early versions of the software.

In the product design phase of the research-based design process, we have analyzed the qualitative data gathered from the participatory design sessions and have made design decisions related to the prototypes. Often we have found out that what teachers or schoolchildren want is not what they need, and by negotiating these conflicts, we have often reach a good consensus with most of the people who have taken part in the sessions.

Later in the research-based design process, we have developed the prototypes by following the principles of agile software development, which consists of short cycles of development that allows getting immediate feedback from the people using the software. In the case of FLE prototypes, they have been tested by thousands of users. From this testing we have collected both quantitative and qualitative data that has been analyzed to inform design decisions for the next iterations of the prototype.

Parallel to the design and development of FLE, learning methods based on collaborative inquiry processes were designed and communicated to thousands of teachers in order to validate the pedagogical approach. By building an FLE prototype and introducing a new learning model –the progressive inquiry– we were able to raise awareness among the educators but not necessarily to change school learning. Still, we may claim today that the experiments carried out with the various FLE prototypes and discussions around them, have shaped in a small way the research field of technology-enhanced learning and computer-supported collaborative learning.

4.2. Square1

Square1 is a prototype that consists of several learning devices designed for collaborative learning at school. The design builds on Sugata Mitra’s Self-Organizing Learning Environments (SOLE) (2012, 2013; Mitra & al. 2010). In SOLE, schoolchildren, working in groups of four in front of a single computer, are given relatively open-ended questions they must answer by searching information from the Internet and by developing their own explanations. While studying in small groups, they may visit other groups and see what they have found out and they can also change groups if they want. This kind of collaborative construction of explanations is expected to engage children in the learning process that Perkins et al. (1995) have characterized as a process of understanding by «working through». By searching and trying to understand in small groups, students are empowered to work with various information sources, to evaluate them, to combine from them explanations with their own level of understanding, and to have sensible and meaningful discussions on difficult topics.

Square1 connects with the move from personal to interpersonal computers (Kaplan & al., 2009). This has strong implications in how we conceptualize collaborative work, learning, and the sort of interactions that we intend to happen in face-to-face situations. In the original SOLE model, four children work in front of a single computer. In practice, the computers are used only to search information related to the topic under study. With the Square1, we wanted to experiment with how devices could exist that are precisely designed for SOLE or a similar kind of collaborative process, that, in addition to searching information from the Internet, supports students to negotiate on the findings, to organize them, and to create new knowledge such as problems, hypothesis, and conclusions about the issues under study.

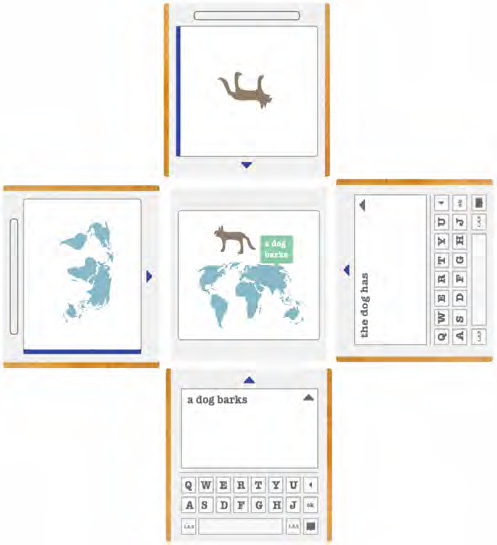

The Square1 prototype set includes three devices: (1) one for writing, (2) one for drawing, and (3) one central computer device for search and presentation composition (figure 3). With these devices, a group of four schoolchildren can do searches on the Internet with the central piece, write notes with the writing devices, and draw pictures with the drawing devices. Working with the central piece is expected to generate negotiation on the reliability and selection of sources, which will be used in the presentation of their research. With the writing and drawing device, children are expected to create content that will be included in the presentation of their findings and explanations. The things written and drawn with the devices can be moved to the central piece, where they are again composed together to be the presentation of the research.

A distinguishing aspect of the Square1 prototype is its connection to and fostering of a maker culture. The Square1 is designed to be assembled by children in school. The blueprints of the cases can be downloaded from a website and manufactured either with computer-aided manufacturing tools such as 3D printers and laser cutters or with traditional handicraft tools such as saws and screwdrivers. From the website, children may also find information about the components needed to assemble the devices and download all the software needed. In this sense, Square1 relates to some extent to the principles of Educational Sloyd, an educational movement started in Finland in the 1860s, which advocated handicraft-based general education. Other references in the Square1 concept come from initiatives, especially in the United States, that promote children as makers (e.g., Tinkering School3, the Mentor Makerspace4 program, and Otherlab)5.

The hypothesis of the Square1 prototype has been that by introducing a set of computer devices that are built by children and precisely designed for SOLE purposes, children will reach a higher level of ownership of their learning, get a better understanding of the technology used in their everyday life, and get engaged to the SOLE kind of learning projects. The experience of building their own learning devices and by using them in learning where they are responsible for the results of learning is expected to have a long-lasting empowering effect on the children.

The design of the Square1 prototype also carries the idea of slow technology. The slowness does not mean slowness of the software running in the device but rather being slow with some tasks when compared to the time needed to complete them with a pen and paper or a laptop computer. This approach is aligned with slow technology where, according to Hallnäs & Redström (2001), slowness is a key factor that could bring forth, and make room for, reflection. In this regard, slow technology should be considered as an attempt to discuss the foundations for design as such in information technology (Glanville, 1999).

During the contextual inquiry of the Square1’s research-based design process, we have visit several schools in Finland to observe their ways of using laptops, tablets, and smartphones as well as trends related to handicraft teaching in schools. In many schools, there are good facilities to assemble devices like the Square1, and the lack of deeper technology education with the information and communication technologies has been recognized by many teachers. The SOLE model is known by some teachers, and there is interest in trying it out in schools. The information gathered and the analyses of it done during the contextual inquiry helped us to define the design challenge.

In the participatory design phase of the research-based design process, we have run 12 workshops with schoolchildren in Finland and in the United States. In these participatory design sessions, children have been creating the initial idea and have developed it further with paper and cardboard prototypes. In the research group, we also have played SOLE with the cardboard prototypes to get a first-hand experience on the learning model and its possible implementation with the Square1 prototype.

Back in our design studios in Helsinki (Finland) and Berkeley (USA), we have analyzed the data from the participatory design sessions and have made design decisions on the development direction of the prototype. Parallel to the hardware design, we have started working on a software prototype. Furthermore, we have started to test potential components available in the market. This way, the product design is already partly mixed with the production of the first functional prototypes.

Square1 is still in the stage of being an early prototype, and the research is a work in progress. Initial testing of the first functional prototypes in a classroom environment will start in the autumn of 2013. In the first stage of testing, we will focus on the use of the devices in the SOLE and then move to the second stage of testing, where children will be asked to assemble their own devices.

5. Discussion and conclusion

As a methodological approach, design thinking and the research-based design process relies on a shared, social construction of understanding with the people who will later use the tools. For instance, Bonsignore et al. (2013) have proposed participatory design techniques in the design of technologies for collaborative learning. When using the design-thinking approach, we may also see that the insights are gained in a dynamic process of «reflection-in-action», where action is used to extend thinking and reflection is governed by the results of action (Schön, 1987).

Design thinking is deeply human-centered system thinking. In the case of CSCL research, it can help researchers take into consideration both the students and the teachers in a system. With research-based design, design research can conclude with prototypes that will have a real impact on the everyday practices of teaching and learning.

The research-based design process aims to meet the challenge of designing for use before it actually has taken place – design for use before use (Redström, 2008). In order to achieve this goal, it is crucial to involve the participants in the design process, allowing them as «owners of problems» to act as designers and to keep the prototypes open for further development (Fischer, Giaccardi, Ye, Sutcliffe & Mehandjiev, 2004). In the research-based design process, it is not possible to decide at first what the problems are and what is needed. Therefore, it is essential for designers to engage in an open dialogue with participants and collaborate with them in a process of shared meaning construction.

Approaching CSCL research with a design-thinking mindset opens the door for more experimental prototypes in which failures are also considered as results. Although in research-based design it is important to be systematic and analytical, creativity, serendipity, and intuition that comes from the art and design traditions can offer valuable input.

Another aspect to take into consideration in the discussion about design thinking and research-based design in CSCL research is the designers’ commitment to service. The tools designed are there to serve the learners and teachers and this should be a driving force throughout the design research process. The utilitarian service approach doesn’t mean that designers should not be aware of theories of pedagogy and social science – quite the opposite. Designers must understand pedagogical ideas and be able to use them in their designs and enrich the field with their contribution. Therefore, we consider that design thinking can be an interesting, alternative approach in CSCL research, especially when the aim is to provide learners and their teachers with CSCL tools that will serve them.

Notes

1 CoVis: www.covis.northwestern.edu (02-09- 2013).

2 Beldevere: http://belvedere.sourceforge.net (02-09- 2013).

3 The Tinkering School, 2012: www.tinkeringschool.com/about (02-09- 2013).

4 Mentor Makerspace, 2013: http://makerspace.com/tag/mentor-makerspace (02-09- 2013).

5 Otherlab: www.otherlab.com (02-09-2013).

Support

The research has been developed in the context of the Learning Design – Design of Learning (LEAD, http://lead.aalto.fi) project. It is partially funded by the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (TEKES).

References

Barab, S.A. & Squire, K. (2004). Design-Based Research: Putting a Stake in the Ground. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14. (DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1).

Bonsignore, E., Ahn, J. & al. (2013). Embedding Participatory Design into Designs for Learning: An Untapped Interdisciplinary Resource? In N. Rummel, M. Kapur, M. Nathan & S. Puntambekar (Eds.), To See the World and a Grain of Sand: Learning across Levels of Space, Time, and Scale. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference on Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, University of Wisconsin, Madison, June 15-19 (pp. 549-556). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Bruce, B.C. (1996). Technology as Social Practice. Educational Foundations, 10(4), 51-58.

Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5-21. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1511637).

Carey, S. & Smith, C. (1995). On Understanding Scientific Knowledge. In D.N. Perkins, J.L. Schwartz, M.M. West, & M.S. Wiske (Eds.), Software Goes to School (pp. 39-55). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2803_4).

Design-Based Research Collective (2003). Design-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational Inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5-8.

Dillenbourg, P., Baker, M., Blaye, A. & O’Malley, C. (1996). The Evolution of Research on Collaborative Learning. In E. Spada & P. Reiman (Eds.), Learning in Humans and Machine: Towards an interdisciplinary learning science, 189-211.

Dillenbourg, P., Järvelä, S. & Fischer, F. (2009). The Evolution of Research on Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning. In N. Balacheff & al. (Eds.), Technology-Enhanced Learning. Principles and Products (pp. 3-19). Netherlands: Springer. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-9827-7_1).

Dunbar, K. & Klahr, D. (1988). Developmental Differences in Scientific Discovery Process. In K. Klahr & K. Kotovsky (Eds.), Complex Information Processing, 109-143. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ehn, P. & Kyng, M. (1987). The Collective Resource Approach to Systems Design. In G. Bjerknes, P. Ehn & M. Kyng (Eds.), Computers and Democracy: A Scandinavian Challenge (pp.17-57). Avebury.

Fallman, D. (2007). Why Research-Oriented Design Isn’t Design-Oriented Research: On the Tensions Between Design and Research in an Implicit Design Discipline. Knowledge, Technology & Policy, 20(3), 193-200. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12130-007-9022-8)

Fischer, G., Giaccardi, E., Ye, Y., Sutcliffe, A.G. & Mehandjiev, N. (2004). Meta-Design: A Manifesto for End-User Development. Communications of the ACM, 47(9), 33-37. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1015864.1015884).

Glanville, R. (1999). Researching Design and Designing Research. Design Issues, 1999; 15:80-92. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1511844).

Hakkarainen, K. (2003). Emergence of Progressive Inquiry Culture in Computer Supported Collaborative Learning. Learning Environments Research, 6: 199-220. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hallnäs, L. & Redstrom, J. (2001). Slow Technology – Designing for Reflection. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5(3), 201-212. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00000019)

Hyysalo, S. (2009). Käyttäjä tuotekehityksessä: tieto, tutkimus, menetelmät. Taideteollisen korkeakoulun julkaisu B. 2. Uudistettu laitos. Helsinki: Taideteollinen korkeakoulu.

Kaplan, F., DoLenh, S. & al. (2009). Interpersonal Computers for Higher Education. In P. Dillenbourg & al. (Eds.), Interactive Artifacts and Furniture Supporting Collaborative Work and Learning. Berlin: Springer. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77234-9_8).

Leinonen, T. (2010). Designing Learning Tools - Methodological Insights. Ph.D. Aalto University School of Art and Design. Jyväskylä: Bookwell. (https://www.taik.fi/-kirjakauppa/images/430c5f77373412b285ef7e32b5d16bd5.pdf) (02-09- 2013).

Leinonen, T., Toikkanen, T. & Silfvast, K. (2008). Software as Hypothesis: Research-Based Design Methodology. In the Proceedings of Participatory Design Conference 2008. Presented at the Participatory Design Conference, PDC 2008, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA: ACM.

Mishra, P. & Koehler, M.J. (2008). Introducing Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. In Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, 1-16. New York.

Mitra, S. (2012). Beyond the Hole in the Wall: Discover the Power of Self-Organized Learning. TED Conferences, LLC.

Mitra, S. (2013). SOLE: How to Bring Self-Organized Learning Environments to Your Community. TED. (www.ted.com/pages/835#public) (02-09- 2013).

Mitra, S., Leat, D., Dolan, P. & Crawley, E. (2010). The Self Organised Learning Environment (SOLE) School Support Pack. ALT Open Access Repository (http://repository.alt.ac.uk/2208) (02-09- 2013).

Nelson, H. & Stolterman, E. (2003). The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World: Foundations and Fundamentals of Design Competence. New Jersey: Educational Technology Publications.

Perkins, D.A., Crismond, D., Simmons, R. & Unger, C. (1995). Inside Understanding. In D.N. Perkins, J.L. Schwartz, M.M. West, & M.S. Wiske (Eds.), Software Goes to School, 70–87. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195115772.003.0005).

Redström, J. (2008). RE: Definitions of Use. Design Studies, 29, 410-423. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2008.05.001).

Rittel, H. & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730).

Scardamalia, M. & Bereiter, C. (1993). Technologies for Knowledge-Building Discourse. Communications of the ACM, 36, 37-41. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/155049.155056).

Scardamalia, M. & Bereiter, C. (2003). Knowledge Building Environments: Extending the Limits of the Possible in Education and Knowledge Work. In A. DiStefano, K.E. Rudestam & R. Silverman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Distributed Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Schwartz, J.L. (1995). Shuttling between the Particular and the General: Reflections on the Role of Conjecture and Hypothesis in the Generation of Knowledge in Science and in Mathematics. In D.N. Perkins, J.L. Schwartz, M.M. West, & M.S. Wiske (Eds.), Software Goes to School, 93-105. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195115772.003.0006).

Schön, D.A. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Stahl, G. (2011). Rediscovering CSCL. In T. Koschmann, R. Hall, N. Miyaki (Eds.), CSCL2: Carrying Forward the Conversation (pp. 169-184). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Varto, J. (2009). Laadullisen tutkimuksen metodologia. Finland: Osuuskunta Elan Vital.

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

El artículo presenta el pensamiento de diseño como un enfoque alternativo para realizar investigaciones sobre aprendizaje colaborativo con tecnología. Se describen dos resultados de investigación a fin de debatir las posibilidades y los retos de aplicar métodos de diseño para diseñar e investigar herramientas de construcción de conocimiento colaborativo. El texto comienza definiendo el aprendizaje colaborativo con nuevas tecnologías como un problema complejo que puede afrontarse mejor mediante la adopción de una actitud de diseñador. Se presenta el Diseño Basado en la Investigación (DBI) como un ejemplo de pensamiento de diseño basado en la construcción social del conocimiento con las personas que más adelante utilizarán las herramientas. Se describen las fases clave que caracterizan el método DBI (investigación contextual, diseño participativo, diseño de producto y software como hipótesis) y defiende la necesidad de adoptar un enfoque de diseño centrado en las personas. Los dos prototipos presentados son la cuarta versión de Future Learning Environment (Fle4), un software para la construcción de conocimiento colaborativo, y Square1, un conjunto de dispositivos y aplicaciones para entornos de aprendizaje auto-organizados. Ambos son ejemplos de DBI y contribuyen a la discusión sobre el rol de los artefactos como resultados de investigación. A través de estos casos, se afirma que el pensamiento de diseño es un enfoque significativo en la investigación sobre el aprendizaje colaborativo mediado por ordenador.

1. Introducción

El término «problema complejo» se utiliza para describir aquellos problemas que son difíciles de resolver ya que están incompletos, sus requisitos cambian constantemente y existen diversos intereses relacionados con los mismos. Las soluciones a los problemas complejos a menudo requieren que muchas personas estén dispuestas a pensar de forma diferente sobre el tema y a cambiar su comportamiento. Los problemas complejos son comunes en la economía, los asuntos sociales, la planificación pública y la política. Una característica de los problemas complejos es que la solución de una parte del problema suele causar otros problemas. En los problemas complejos no hay respuestas verdaderas o falsas, sino buenas o malas soluciones (Rittel & Webber, 1973).

La enseñanza, el aprendizaje con la tecnología en general, y el Aprendizaje Colaborativo Mediado por Ordenador (CSCL), en particular, pueden verse como un problema complejo (Mishra & Koehler, 2008; Leinonen, 2010). Muchos de los problemas relacionados con el aprendizaje colaborativo y los ordenadores están incompletos y son contradictorios. En las prácticas en entorno CSCL hay muchos actores con interdependencias diferentes y complejas, incluidos los docentes, los alumnos, y los ordenadores interconectados. Según Mishra y Koehler (2008), los investigadores que trabajan en el campo deben reconocer la complejidad de las situaciones en el contexto educativo con los alumnos, los profesores y la tecnología. En este sentido, existe una demanda creciente de colaboración entre investigadores, diseñadores, profesores y alumnos durante el proceso de diseño de las tecnologías para el aprendizaje (Dillenbourg & al., 2009; Bonsignore & al., 2013).

El pensamiento de diseño se ha identificado como un enfoque significativo para hacer frente a los problemas complejos (Buchanan, 1992). Por ejemplo, de acuerdo con Nelson y Stolterman (2003), el diseño no tiene por objeto resolver un problema con una respuesta definitiva, sino crear una adición positiva a la situación actual. De esta manera, el diseño difiere significativamente de la solución de problemas ordinarios. Los diseñadores no ven el mundo como si en algún lugar hubiera un diseño perfecto que deberían descubrir, sino que su objetivo es contribuir a la situación actual con su diseño. Así, el diseño es una actividad exploratoria donde se cometen errores que posteriormente se solucionan. Poéticamente, se puede decir que el diseño es navegación sin un mapa claro, basándose únicamente en el contexto actual y en la información obtenida de él.

La base epistemológica del pensamiento de diseño es que la mayor parte del mundo en que vivimos es modificable, algo en lo que nosotros, como seres humanos, podemos tener un impacto. En el pensamiento de diseño, las personas se ven como actores que pueden marcar una diferencia. La gente puede diseñar soluciones relevantes que tendrán un impacto positivo. De este modo, el pensamiento de diseño es un estado mental que se caracteriza por estar centrado en lo humano, social, responsable, optimista y experimental.

En este artículo presentamos el pensamiento de diseño como un enfoque alternativo para llevar a cabo la investigación en el campo de CSCL. Para demostrar los resultados del pensamiento de diseño basado en la investigación en torno a CSCL, presentamos dos artefactos generados con este enfoque. Empezamos con una discusión general sobre el diseño y el pensamiento de diseño seguida de una descripción de nuestro enfoque metodológico. A continuación, presentamos dos resultados de nuestra investigación en el campo de CSCL, que obtuvimos utilizando un enfoque fuertemente influenciado por el pensamiento de diseño. Los resultados son aplicaciones diseñadas para la construcción colaborativa del conocimiento (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2003) y el aprendizaje colaborativo en un entorno de aprendizaje auto-organizado (Mitra, 2013).

2. Pensamiento de diseño en contexto

La investigación en diseño a menudo comienza con la observación, la reflexión y el cuestionamiento. Un investigador en diseño con actitud interrogativa se interesa especialmente por las prácticas cotidianas. Este puede darse cuenta de que muchas cosas que se consideran como normales, naturales e inmutables son realmente problemáticas. Un investigador en diseño con actitud interrogativa está interesado en reflexionar sobre el significado de su investigación para la vida humana en general y para las distintas prácticas humanas en un contexto cotidiano. Las personas involucradas en la investigación se ven como parte de la misma realidad humana. En la investigación, las personas no son objetos de la investigación, sino sujetos de ésta. Un investigador en diseño con actitud interrogativa no considera que su trabajo sea producir hechos neutrales o ser neutral en absoluto. Por lo tanto, la reflexión y discusión sobre el valor y su impacto en la investigación son una gran parte de la investigación. La labor de un investigador en diseño con actitud interrogativa tiene un significado ético como evaluador de la existencia humana y del comportamiento (Varto, 2009; Leinonen, 2010).

En la investigación en diseño interrogativo, la atención se centra no solo en la estética y la facilidad de uso, sino que se tienen en cuenta cuestiones mucho más amplias y fundamentales. Por ejemplo, Hyysalo (2009) clasifica el diseño en cinco niveles diferentes. Para ilustrar los diferentes niveles de diseño, podemos utilizar, a modo de ejemplo, el diseño del botón de encendido de un teléfono móvil.

1) En el primer nivel, el diseño está en los detalles. Por ejemplo, el diseño físico de la forma del botón de encendido del teléfono móvil, el icono y el color es un diseño de los detalles.

2) En el segundo nivel, está el diseño de la interfaz de usuario. La decisión de mantener pulsado el botón de encendido durante un segundo y a continuación el teléfono reacciona con una vibración para indicar que se está iniciando es un ejemplo de diseño de interfaz de usuario.

3) En el tercer nivel de diseño, el interés está en los sistemas. La lógica según la cual el teléfono mantiene su ajuste a pesar de que esté apagado responde al diseño de todo el sistema de software que se ejecuta en el teléfono.

4) El cuarto nivel en el diseño incluye temas sociales. Por ejemplo, la funcionalidad incluida en el botón de encendido de un teléfono móvil que permite ponerlo en modo silencioso o en modo de reunión es una decisión que responde a los contextos sociales en los que se utiliza el teléfono.

5) El quinto nivel en el diseño tiene en cuenta implicaciones sociales más amplias. La decisión de desconexión con el botón de encendido que impide que el teléfono sea rastreado puede ser una decisión tomada para proteger la privacidad del usuario.

Las decisiones que afectan a los diferentes niveles de diseño no se pueden tomar por separado ya que están interconectadas y se influyen mutuamente. La complejidad del diseño requiere la investigación, la capacidad de ver tanto el conjunto como los detalles, y la habilidad para analizarlos.

El diseño puede proporcionar a la gente una idea de las nuevas formas de hacer las cosas y de las diferentes perspectivas e interpretaciones acerca de la realidad que están viviendo. De esta manera, el diseño puede ser una forma de enfrentar la complejidad y responder a la voluntad de la gente de cambiar deliberadamente el mundo (Nelson & Stolterman, 2003). Cuando se incluyen interpretaciones de la complejidad, el diseño no puede ser nunca una actividad neutral. Detrás del diseño, podemos encontrar ideas y principios cargados de valores, incluso de ideología. Tal y como destaca Bruce (1996), no es solo que los significados de estos artefactos se construyan socialmente, sino que el diseño físico y las prácticas sociales en torno a ellos también se construyen socialmente. Entender el diseño como una construcción social y los resultados del diseño como algo que va a tener un impacto real en la realidad socialmente construida que la gente vive, requiere responsabilidad y rendición de cuentas por parte de los diseñadores y de las personas que participan en el diseño.

La tradición escandinava de diseño participativo es uno de los primeros modelos de pensamiento de diseño. En el diseño participativo, las personas que se espera que sean los beneficiarios de un diseño están invitadas a participar en el proceso desde las primeras etapas. Mediante la participación de las personas en el proceso, se espera que los resultados en conjunto sean mejores que si se hace sin ellas. Por ejemplo, Ehn y Kyng (1987), los cuales han hecho investigación en diseño relacionada con los ordenadores en los centros de trabajo, se han percatado de que el diseño de una herramienta informática no es solo el diseño de una herramienta, sino que también tiene consecuencias en los procesos de trabajo y en todo el lugar de trabajo. La adopción del aprendizaje colaborativo en la educación presenta problemas similares, ya que requiere repensar la cultura del aula, así como los objetivos curriculares y el marco institucional (Stahl, 2011). Por lo tanto, el reconocimiento de las personas como principal fuente de innovación es crucial para obtener diseños que sirvan a las necesidades de las personas que van a trabajar, aprender o enseñar con las herramientas diseñadas. Esto significa que, simultáneamente al diseño de la herramienta, se requiere que la comunidad reconsidere y rediseñe parcialmente sus procesos de trabajo actuales.

En primer lugar, el pensamiento de diseño, en el caso del diseño de herramientas para el CSCL, significa que los investigadores trabajarán simultáneamente en los diferentes niveles de diseño. En lugar de permitir solo la colaboración, un entorno de aprendizaje colaborativo exitoso crea las condiciones para interacciones grupales eficaces (Dillenbourg & al., 2009). En el diseño de herramientas, los investigadores deben adoptar una comprensión compleja de las interacciones en grupos y considerar las implicaciones sociales de su trabajo, pero también tomar decisiones sobre la experiencia de usuario, la interfaz y sus detalles. En segundo lugar, en el diseño de herramientas para el CSCL, debemos ser conscientes de los diferentes intereses entre los distintos grupos implicados. En el caso de la educación, hay, por ejemplo, diferentes bases de valores, ideologías y enfoques pedagógicos que a menudo son difíciles de aunar. Los diseñadores deben defender algo y ser transparentes acerca de las decisiones basadas en valores tomadas en el proceso. En tercer lugar, los profesores y los alumnos deben tener voz en el proceso de diseño, y el objeto de diseño no solo debe ser la herramienta para el CSCL, sino todo el proceso y las prácticas de aprendizaje en la escuela.

3. Enfoque metodológico: Investigación e intervenciones de diseño

Para abordar el problema complejo en el CSCL, hemos utilizado el diseño basado en la investigación como enfoque metodológico (Leinonen & al., 2008; Leinonen, 2010). En el diseño basado en la investigación es esencial ver los resultados del diseño –los artefactos– como resultados primarios y principales resultados de la actividad. De esta manera, los artefactos, por su parte, permiten debatir los resultados de la investigación.

El proceso de diseño basado en la investigación es una praxis de investigación inspirada en las teorías de diseño (Ehn & Kyng, 1987; Schön, 1987; Nelson & Stolterman, 2003). Hace hincapié en las soluciones creativas, experimentos lúdicos y en la construcción de prototipos. Se alienta a los investigadores y diseñadores a probar diferentes ideas y conceptos. El proceso de diseño basado en la investigación se puede describir como un proceso continuo de definición y redefinición de los problemas y oportunidades de diseño, así como el diseño y rediseño de prototipos. La mayoría de las actividades se realiza en un estrecho diálogo con la comunidad que previsiblemente utilizará las herramientas diseñadas. El proceso se puede dividir en cuatro fases principales, aunque todas ellas ocurren al mismo tiempo y en paralelo (figura 1). En diferentes momentos de la investigación, se requiere que los investigadores dediquen más esfuerzo a diferentes fases. La iteración continua, sin embargo, requiere que los investigadores mantengan vivas todas las fases todo el tiempo.

En la primera fase –la investigación contextual– la atención se centra en la exploración del contexto socio-cultural del diseño. El objetivo es entender el entorno, la situación y la cultura donde el diseño se lleva a cabo. Los resultados de la investigación contextual consisten en la mejor comprensión del contexto, al reconocer en ella los posibles retos y oportunidades de diseño. En esta fase, los investigadores en diseño utilizan métodos etnográficos rápidos, como la observación participante, anotaciones, bocetos, conversaciones informales y entrevistas. Paralelamente al trabajo de campo, los investigadores en diseño hacen una revisión focalizada de la literatura, la evaluación comparativa de las soluciones existentes y analizan las tendencias en el área con el fin de desarrollar una visión de los problemas de diseño.

En la segunda fase –diseño participativo– se llevan a cabo talleres con las partes interesadas. Los talleres se basan en los resultados de la investigación contextual. En pequeños grupos de 4-6, se discuten y se siguen desarrollando los resultados de la investigación contextual. Una práctica común es presentar los resultados como escenarios realizados por los investigadores que contienen desafíos y oportunidades de diseño. En el taller, se invita a los participantes a encontrar soluciones de diseño para los desafíos y aportar a la discusión nuevos retos y soluciones. Más adelante, se organizan nuevos talleres de diseño participativo para discutir los primeros prototipos.

Los resultados del diseño participativo se analizan en el estudio de diseño por los investigadores y se utilizan para crear los primeros prototipos que luego se prueban y validan de nuevo en las sesiones de diseño participativo. Al mantener una distancia de las partes interesadas, en la fase de diseño del producto, los investigadores en diseño tienen la oportunidad de analizar los resultados del diseño participativo, clasificarlos, utilizar el lenguaje de diseño específico relacionado con la implementación de los prototipos y, finalmente, tomar decisiones de diseño.

En última instancia, los prototipos se desarrollan para ser funcionales a un nivel en el que puedan probarlos personas reales en sus situaciones cotidianas. Los prototipos todavía se consideran una hipótesis, prototipos como hipótesis, ya que se espera que sean parte de las soluciones para los retos definidos y redefinidos durante la investigación. A las partes interesadas les queda decidir si confirman las afirmaciones hechas por los investigadores en diseño.

El diseño basado en la investigación no se debe confundir con la investigación basada en el diseño (Barab & Squire, 2004; Design-Based Research Collective, 2003; Fallman, 2007; Leinonen & al., 2008). En el diseño basado en la investigación, que se fundamenta en la tradición de arte y diseño, la atención se centra en los artefactos, los resultados finales del diseño. La forma de ser de los artefactos y las posibilidades y características que tienen o no, forman una parte importante de la argumentación de la investigación. Como tal, el diseño basado en la investigación como enfoque metodológico incluye la investigación y las intervenciones de diseño, quedando todos entrelazados.

4. Resultados: Los prototipos FLE4 y Square1

Mediante la adopción de un enfoque inspirado en el pensamiento de diseño y el proceso de diseño basado en la investigación descrito en las secciones anteriores, hemos diseñado y desarrollado dos prototipos de herramientas CSCL: 1) la cuarta versión de Future Learning Environment (Fle4), un programa de software basado en la Web para la construcción colaborativa del conocimiento; 2) Square1, una colección de dispositivos de aprendizaje diseñados para el aprendizaje colaborativo en la escuela.

Fle4 y Square1 se basan en el aprendizaje socioconstructivista y la teoría de la zona de desarrollo próximo de Lev Vygostky. Los prototipos están diseñados para ayudar y guiar el proceso de construcción social del conocimiento de los alumnos, el cual se distribuye entre la gente y sus herramientas en uso. El fundamento pedagógico ha tenido un gran impacto en el diseño de los prototipos. Por ejemplo, los prototipos están diseñados para que los alumnos no solo construyan conocimientos, sino que también tengan un papel en la cocreación de su entorno de aprendizaje.

Fle4 y Square1 se han diseñado basándose en las últimas investigaciones en CSCL, en las cuales los investigadores han hecho hincapié en la importancia de involucrar a estudiantes y profesores en esfuerzos coordinados para construir nuevos conocimientos y resolver problemas juntos (Dillenbourg, & al., 1996). Al igual que en otros entornos como CoVis1, CoNotes, Belvedere2, y Clare, la investigación de los dos prototipos se ha centrado en ampliar y probar las teorías de la producción colaborativa, el discurso de construcción del conocimiento y el uso de andamios (scaffolding). A continuación, presentamos las herramientas, Square1 y FLE4, y describimos con más detalle el diseño de la investigación en las diferentes fases del proceso de diseño basado en la investigación.

4.1. FLE4: Future Learning Environment 4

Fle4 (Future Learning Environment 4) es una herramienta para la construcción de conocimiento diseñada para funcionar en la plataforma de blogs WordPress (http://fle4.aalto.fi/about). Fle4 es la última iteración, así como la última versión de la investigación sobre FLE iniciada en 1998. A lo largo de los años, hemos publicado cuatro prototipos funcionales: FLE (1988-99), Fle2 (2000-01), Fle3 (2002) y Fle4 (2012). FLE estaba originalmente dirigido a los niños, maestros y padres en Finlandia. Más adelante, la investigación se continuó en un contexto europeo. En el caso de Fle3, la herramienta se ha utilizado en todos los continentes y la interfaz de usuario se ha traducido a más de 20 idiomas. Incluso hoy en día, Fle3 se sigue utilizando en algunas escuelas de Educación Primaria y Secundaria.

El desafío que motivó el diseño original de FLE fue la observada falta de instrumentos para las actividades de creación de conocimiento centrado en los estudiantes en las escuelas de Finlandia. Aunque estas ideas eran discutidas entre los maestros y en las escuelas de formación del profesorado, se observó que las prácticas reales en las aulas seguían siendo tradicionales y difíciles de cambiar. Por consiguiente, FLE se pensó para apoyar el aprendizaje basado en la Investigación Progresiva (Hakkarainen, 2003), un modelo de aprendizaje desarrollado en paralelo a FLE. La Investigación Progresiva es una forma de aprendizaje donde profesores y alumnos participan en mantener una construcción continua del conocimiento a través de diferentes materias escolares. La idea es imitar las prácticas de trabajo de conocimiento intensivo, un proceso que es común entre grupos de investigación científica.

Al igual que otras herramientas centradas en la investigación colaborativa, FLE tiene como objetivo facilitar la comprensión de alto nivel al requerir que los estudiantes formulen preguntas para generar explicaciones y teorías sobre los fenómenos que se investigan (Bruner, 1996; Carey & Smith, 1995; Dunbar & Klahr, 1988; Perkins & al., 1995; Scardamalia y Bereiter, 1993; Schwartz, 1995). Implicar a los alumnos en formular nuevas preguntas y explicaciones es un tema clave ya que los estudiantes están más acostumbrados a encontrar respuestas a las preguntas ya existentes que a plantear nuevas.

La hipótesis de los prototipos FLE consistía en que una herramienta para el aprendizaje colaborativo mediado por ordenador bien diseñada podría impulsar la inclusión de más actividades de creación de conocimientos en el aula y, por consiguiente, cambiar las prácticas pedagógicas existentes en las escuelas. Como el primer prototipo completo de FLE, Fle3 ofreció un espacio digital en el que los miembros de la comunidad de aprendizaje podían encontrar: 1) Web-tops para que los estudiantes recopilaran y compartieran información, 2) una herramienta de construcción de conocimiento para la discusión en línea mediante andamios con el objetivo de aumentar el nivel de conocimiento y comprensión sobre el tema objeto de la investigación y 3) una herramienta para el desarrollo de la improvisación, de un modo similar a como sucede en el jazz, en el diseño colaborativo de los artefactos digitales del grupo.

Como última versión, Fle4 se basa en el trabajo realizado sobre el diseño de Fle3. Fle4 ofrece una herramienta para la construcción del conocimiento que se puede integrar y utilizar con un servicio de blog. En comparación con la herramienta de construcción de conocimiento Fle3, Fle4 ofrece vistas visuales y ampliables del discurso en forma de red (figura 2). Con ello se espera ayudar a los estudiantes a hacer un seguimiento de las diversas actividades en el discurso sobre la construcción del conocimiento, así como a organizar las notas en función de su importancia. Fle4 también proporciona formas más ventajosas para explorar el discurso de la construcción del conocimiento al agrupar las notas según los autores y los tipos de conocimiento utilizados. Los estudiantes también pueden ver las notas en una línea temporal.

En el diseño de la investigación de las diferentes versiones de FLE, el estudio contextual del proceso de diseño se ha centrado en las prácticas de aprendizaje en la escuela y en las posibilidades de cambiar algunas de ellas. Mediante el estudio de alumnos, profesores y padres pudimos reconocer la necesidad de cambiar la práctica, aunque también nos dimos cuenta de que esto puede ser muy difícil y puede llevar mucho tiempo. Otra observación clave se relaciona con los cambios que ocurren en toda la infraestructura de conocimiento: las conexiones a Internet y los ordenadores en las escuelas debían desafiar el aprendizaje escolar tradicional, aunque, al mismo tiempo, servicios tales como los sistemas de gestión de aprendizaje (LMS) proporcionados a las escuelas se basaban en los métodos tradicionales de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Con FLE, queríamos, y todavía queremos, presentar un enfoque alternativo en el uso de los ordenadores y de Internet en el aprendizaje escolar: más centrado en el estudiante, con un fuerte énfasis en el trabajo colaborativo con el conocimiento.

Como parte del proceso de investigación basado en el diseño de FLE, hemos llevado a cabo numerosas sesiones de diseño participativo con los profesores y los alumnos en varios países europeos. En éstas, hemos diseñado funcionalidades con docentes y niños, y hemos probado prototipos en papel y las primeras versiones del software.

En la fase de diseño de producto del proceso de diseño basado en la investigación, se han analizado los datos cualitativos obtenidos en las sesiones de diseño participativo y hemos tomado decisiones de diseño relacionadas con los prototipos. Muchas veces nos hemos dado cuenta de que lo que los maestros o alumnos quieren no es lo que necesitan, y mediante la negociación de estos conflictos, a menudo hemos llegado a un buen acuerdo con la mayoría de las personas que han participado en las sesiones.

Más adelante en el proceso de diseño basado en la investigación, hemos desarrollado los prototipos siguiendo los principios del desarrollo ágil de software, que consiste en ciclos cortos de desarrollo a fin de obtener información inmediata de las personas que utilizan el software. En el caso de los prototipos de FLE, miles de usuarios los han probado. De estas pruebas se han recopilado datos cuantitativos y cualitativos que se han analizado, para informar las decisiones en el diseño en las siguientes iteraciones del prototipo.

Paralelamente al diseño y desarrollo de FLE, los métodos basados ??en los procesos de investigación colaborativa de aprendizaje se diseñaron y comunicaron a miles de maestros con el fin de validar el enfoque pedagógico. Con la construcción de un prototipo de FLE y la introducción de un nuevo modelo de aprendizaje –la investigación progresiva– hemos sido capaces de concienciar a los educadores, pero no necesariamente de cambiar el aprendizaje escolar. Sin embargo, hoy podemos afirmar que los experimentos llevados a cabo con los diferentes prototipos FLE y las discusiones sobre ellos han dado forma, de manera limitada, al campo de investigación en torno al aprendizaje mediado por tecnología y aprendizaje colaborativo mediado por ordenador.

4.2. Square1

Square1 es un prototipo que consta de varios dispositivos de aprendizaje diseñados para el aprendizaje colaborativo en la escuela. El diseño se basa en los entornos de aprendizaje autorganizados (SOLE) de Sugata Mitra (2012; 2013; Mitra & al., 2010). En Sole, los alumnos, trabajando en grupos de cuatro en frente de un ordenador, reciben preguntas relativamente abiertas que deben responder buscando información a través de Internet y mediante el desarrollo de sus propias explicaciones. Mientras estudian en pequeños grupos, pueden visitar otros grupos y ver lo que han descubierto, y también pueden cambiar de grupo si lo desean. Se espera que este tipo de construcción colaborativa de explicaciones implique a los niños en el proceso de aprendizaje que Perkins y otros (1995) han caracterizado como un proceso de comprensión por «trabajo a través». Al realizar búsquedas y tratar de entender en pequeños grupos, los estudiantes tienen la facultad de trabajar con diversas fuentes de información, evaluarlas, establecer relaciones y generar explicaciones con su propio nivel de comprensión, así como tener discusiones sensibles y significativas sobre temas difíciles.

Square1 conecta con el paso del ordenador personal a los ordenadores interpersonales (Kaplan & al., 2009). Esto tiene importantes implicaciones en la forma en que conceptualizamos el trabajo colaborativo, el aprendizaje y el tipo de interacciones que pretendemos favorecer en situaciones cara a cara. En el modelo SOLE original, cuatro niños trabajan delante de un ordenador. En la práctica, los ordenadores solo se utilizan para buscar información relacionada con el tema objeto de estudio. Con Square1, hemos querido experimentar cómo podrían existir dispositivos que están diseñados precisamente para SOLE o para otros procesos de colaboración similares que, además de buscar información en Internet, apoyen a los estudiantes para negociar los resultados, organizarlos, así como para crear nuevos conocimientos, como problemas, hipótesis y conclusiones sobre los temas objeto de estudio.

El prototipo Square1 incluye tres dispositivos: uno para la escritura, uno para el dibujo y un dispositivo de ordenador central para la búsqueda y composición de la presentación (figura 3). Con estos dispositivos, un grupo de cuatro niños en edad escolar puede hacer búsquedas en Internet con la pieza central, escribir notas con los dispositivos de escritura y hacer dibujos con los dispositivos de dibujo. Se espera que el trabajo con el dispositivo central genere negociación sobre la fiabilidad y la selección de las fuentes que se utilizarán en la presentación de su investigación. Con los dispositivos de escritura y dibujo, se espera que los niños creen contenido que se incluya en la presentación de sus conclusiones y explicaciones. Los materiales escritos y dibujados con los dispositivos se pueden enviar al ordenador central, donde se componen juntos de nuevo para la presentación de la investigación.

Un aspecto distintivo del prototipo Square1 es su conexión y el fomento de una cultura centrada en el hacer. Square1 está diseñado para que lo monten los niños en la escuela. Los planos de las carcasas se pueden descargar de una página web y se pueden fabricar ya sea con herramientas de fabricación asistida por ordenador, como impresoras 3D y cortadores láser, o con herramientas artesanales tradicionales, tales como sierras y destornilladores. En la página web, los niños también pueden encontrar información acerca de los componentes necesarios para montar los dispositivos y descargar todo el software necesario. En este sentido, Square1 se relaciona en cierta medida con los principios de la Educación Sloyd, un movimiento educativo iniciado en Finlandia en la década de 1860, que abogaba por la educación general a base de artesanía. Otras referencias en el concepto de Square1 provienen de iniciativas, sobre todo en Estados Unidos, que promueven los niños como los fabricantes (por ejemplo, Tinkering School3, el programa Mentor Makerspace4 y Otherlab5).

La hipótesis del prototipo Square1 ha sido que, mediante la introducción de un conjunto de dispositivos informáticos construidos por los niños y diseñados precisamente para fines SOLE, los niños desarrollarían un mayor sentido de propiedad de su aprendizaje, tendrían una mejor comprensión de la tecnología utilizada en su vida cotidiana, y se implicarían con el tipo de proyectos de aprendizaje basados en SOLE. Se espera que la experiencia de construir sus propios dispositivos de aprendizaje y usarlos en el aprendizaje donde ellos son los responsables de los resultados de su aprendizaje tenga un efecto de empoderamiento duradero en los niños.

El diseño del prototipo Square1 también se basa en la idea de tecnología lenta. La lentitud no significa lentitud del software que se ejecuta en el dispositivo, sino en la realización de algunas tareas en comparación con el tiempo necesario para completarlas con lápiz y papel o con un ordenador portátil. Este enfoque se alinea con la tecnología lenta donde, según Hällnäs y Redström (2001), la lentitud es un factor clave que podría dar lugar a la reflexión y generar espacio para ésta. En este sentido, la tecnología lenta debe considerarse como un intento de discutir las bases para el diseño como tal en la tecnología de la información (Glanville, 1999).

Durante la investigación contextual del proceso de diseño basado en la investigación de Square1, hemos visitado varias escuelas en Finlandia para observar las formas de utilización de los ordenadores portátiles, tabletas y teléfonos inteligentes, así como las tendencias relacionadas con la enseñanza de la artesanía. En muchas, hay buenas instalaciones para montar dispositivos como Square1, y muchos profesores han reconocido la falta de una educación tecnológica más profunda con las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación.

Algunos docentes conocen el modelo SOLE y hay interés en llevarlo a cabo en las escuelas. La información recogida y el análisis de los mismos, realizados durante la investigación contextual nos ayudó a definir el desafío del diseño.

En la fase de diseño participativo del proceso de diseño basado en la investigación, hemos llevado a cabo 12 talleres con escolares en Finlandia y en los Estados Unidos. En estas sesiones de diseño participativo, los niños han creado la idea inicial y la han desarrollado aún más en papel y con prototipos de cartón. En el grupo de investigación, también hemos experimentado SOLE con los prototipos de cartón para experimentar de primera mano el modelo de aprendizaje y analizar su posible aplicación en el prototipo Square1. Ya en nuestros estudios de diseño en Helsinki (Finlandia) y Berkeley (EEUU), hemos analizado los datos de las sesiones de diseño participativo y hemos tomado las decisiones de diseño en la dirección de desarrollo del prototipo. Paralelamente al diseño del hardware, hemos empezado a trabajar en un prototipo de software. Además, hemos comenzado a probar los componentes potenciales disponibles en el mercado. De esta manera, el diseño del producto ya está en parte mezclado con la producción de los primeros prototipos funcionales.

Square1 se encuentra todavía en una etapa temprana de prototipo y la investigación es un trabajo en curso. Las pruebas iniciales de los primeros prototipos funcionales en un entorno de clase comenzarán en otoño de 2013. En la primera etapa de las pruebas, nos centraremos en el uso de los dispositivos en SOLE y luego pasaremos a una segunda fase, en la que se pedirá a los niños que monten sus propios dispositivos.

5. Discusión y conclusión

Como enfoque metodológico, el pensamiento de diseño y el proceso de diseño basado en la investigación se centran en la construcción social compartida del entendimiento con la gente que más tarde utilizará las herramientas. Por ejemplo, Bonsignore y otros (2013) han propuesto técnicas de diseño participativo en el diseño de tecnologías para el aprendizaje colaborativo. Cuando se utiliza el enfoque basado en el pensamiento de diseño, también podemos ver que las ideas se obtienen en un proceso dinámico de «reflexión en la acción», donde se utiliza la acción para extender el pensamiento y la reflexión se rige por los resultados de la acción (Schön, 1987).

El pensamiento de diseño es un sistema de pensamiento profundamente centrado en el humano. En el caso de la investigación en CSCL, puede ayudar a los investigadores a tener en cuenta tanto a estudiantes como a profesores en un sistema. Con el diseño basado en la investigación, la investigación del diseño puede concluir con prototipos que tendrán un impacto real en las prácticas cotidianas de enseñanza y aprendizaje.

El proceso de diseño basado en la investigación tiene como objetivo hacer frente al desafío de diseñar para su uso antes de que éste haya tenido lugar realmente –diseño para el uso antes de su uso (Redström, 2008)–. Para lograr este objetivo, es fundamental involucrar a los participantes en el proceso de diseño permitiéndoles, como «propietarios de los problemas», actuar como diseñadores y mantener los prototipos abiertos para un mayor desarrollo (Fischer, & al., 2004). En el proceso de diseño basado en la investigación no es posible decidir en un principio cuáles son los problemas y qué se necesita. Por lo tanto, para los diseñadores es esencial participar en un diálogo abierto con los participantes y colaborar con ellos en un proceso de construcción de significados compartidos.

Abordar la investigación en CSCL con una mentalidad propia del pensamiento de diseño abre la puerta a prototipos más experimentales en los cuales los fracasos también se consideran resultados. Aunque en el diseño basado en la investigación es importante ser sistemático y analítico, algunos valores procedentes del arte y de las tradiciones de diseño como la creatividad, la casualidad y la intuición también pueden ofrecer información valiosa.

Otro aspecto a tener en cuenta en la discusión sobre el pensamiento de diseño y en el diseño basado en la investigación en los estudios en torno a CSCL es el compromiso de los diseñadores con el servicio. Las herramientas diseñadas están ahí para servir a los estudiantes y maestros, y esto debe ser una fuerza impulsora en todo el proceso de investigación del diseño. El enfoque de servicio utilitarista no quiere decir que los diseñadores no deban estar al tanto de las teorías en pedagogía y ciencias sociales, sino todo lo contrario. Los diseñadores deben entender las ideas pedagógicas y poder usarlas en sus diseños y así enriquecer el campo con su contribución. Por lo tanto, consideramos que el pensamiento de diseño puede ser un interesante enfoque alternativo en la investigación en torno a CSCL, especialmente cuando el objetivo es proporcionar a los estudiantes y a sus profesores herramientas en CSCL que les sirvan.

Notas

1 CoVis: www.covis.northwestern.edu (02-09- 2013).

2 Belvedere: http://belvedere.sourceforge.net (02-09- 2013).

3 The Tinkering School: www.tinkeringschool.com/about (02-09-2013).

4 Mentor Makerspace, 2013: http://makerspace.com/tag/mentor-makerspace (02-09- 2013).

5 Otherlab: www.otherlab.com (02-09-2013).

Apoyos

La investigación se ha desarrollado en el contexto del proyecto «Learning Design, Design of Learning» (LEAD) (http://lead.aalto.fi). Este proyecto está financiado parcialmente por la Agencia Finlandesa de Financiación de Tecnología e Innovación (TEKES).

Referencias

Barab, S.A. & Squire, K. (2004). Design-Based Research: Putting a Stake in the Ground. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14. (DOI: http://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1).

Bonsignore, E., Ahn, J. & al. (2013). Embedding Participatory Design into Designs for Learning: An Untapped Interdisciplinary Resource? In N. Rummel, M. Kapur, M. Nathan & S. Puntambekar (Eds.), To See the World and a Grain of Sand: Learning across Levels of Space, Time, and Scale. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference on Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, University of Wisconsin, Madison, June 15-19 (pp. 549-556). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Bruce, B.C. (1996). Technology as Social Practice. Educational Foundations, 10(4), 51-58.

Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buchanan, R. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5-21. (DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1511637).