Pulsa aquí para ver la versión en Español (ES)

Abstract

Technologies have acquired strategic importance and have been defined as unprecedented educational tools. In this study, we analysed the use that 1,488 Spanish adolescents made of five tools (i.e. search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging), and the impact that use of these tools had on their academic performance in science, mathematics, Spanish language and English. To this end, we explored frequency of use, time spent, purpose, place of use and level of satisfaction for each of the tools, as well as academic performance in the four subjects analysed, using the HEGECO instrument. Results revealed differential patterns in the use of technologies according to purpose, and in academic performance according to sex, age and use of the tools. Adolescents used search engines and wikis to carry out academic tasks, and podcasts for entertainment. In relation to academic performance, females presented better mean performance in linguistic subjects, and younger adolescents did so in all the subjects analysed. In relation to use of tools, the use of search engines was associated with better performance in science, Spanish language and English, while the use of podcasts was associated with better performance in mathematics. The implications of these results are discussed and evaluated.

1. Introduction

Learning and knowledge technologies have been defined as ‘unprecedented educational tools’ (Pantoja & Huertas, 2010: 225). They encompass search engines, wikis, blogs, instant messaging and podcasts or video and audio files that allow users to create, collaborate, connect, share and participate in a learning community (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2013; Yuen & Yuen, 2010).

Recent years have witnessed the steady incorporation of technologies in schools (Bocyl, 2015). Hence, the variables that have traditionally been related to academic performance must now be expanded to include technologies, especially those that correspond to the institutional technology environment, accessibility and internet use. These tools are viewed as new determinants of academic performance since they affect student work at different levels and in different ways (Duart, Gil, Pujol, & Castaño, 2008; Han & Shin, 2016; Torres-Díaz, Duart, Gómez-Alvarado, Marín-Gutiérrez, & Segarra-Faggioni, 2016).

Several authors have examined young people’s use of technologies and the impact of some of these tools on their academic performance (Junco, 2015; Noshahr, Talebi &, Mojallal, 2014; Wentworth & Middleton, 2014). Tools such as wikis are a widely used resource among adolescents (Soler-Adillon, Pavlovic, & Freixa, 2018), as is instant messaging, which facilitates direct personal communication and thus increases trust and a sense of intimacy among young people (Cetinkaya, 2017; Noshahr, Talebi, & Mojallal, 2014).

Furthermore, seeking information on the Internet involves selecting appropriate sources and then extracting, organising and integrating the information obtained, helping students acquire problem-solving abilities. Furthermore, participation in chats improves communication and interaction skills (Jonassen & Kwon, 2001; Ndege, & al., 2015; Tabatabai & Shore, 2005).

In support of these assertions, the results of various studies show that both computer use and the type of activity engaged in contribute significantly to explain not only the academic performance in young people but also the greater academic success in higher education achieved by those who make balanced use of technologies (Gil, 2012; Torres-Díaz & al., 2016).

In contrast, other studies have found no relationship between academic performance and technology usage and access to education, reporting no significant correlation between marks and the time students spend using technologies (Noshahr, Talebi, & Mojallal, 2014). It has also been reported that the use of technologies can affect student performance in one particular area but not in others. For example, it has been found that computer use in education does not contribute significantly to improving students’ performance in mathematics, but does do so in science (Antonijevic, 2007; Wittwer & Senkbeil, 2008).

Research has yielded contradictory results, underlining the need to conduct new studies that analyse students’ technology usage patterns. Likewise, it is also necessary to determine use of these tools in schools and its influence on students’ academic performance during adolescence, a stage characterised by psychosocial and cognitive changes that are being affected by the exponential increase in the use of technologies (Montes-Vozmediano, García-Jiménez, & Menor-Sendra, 2018; Risso, Peralbo, & Barca, 2010).

Hence, the aim of this study was to analyse adolescent students’ use of five technologies and determine the impact of these on their academic performance.

1.1. Research questions

In order to determine whether the use of technology influences adolescent students’ academic performance and achievement, we investigated: (i) adolescent students’ use of five technology tools (search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging) and (ii) the impact of the use of these tools on adolescent students’ academic performance.

Our research questions were as follows:

1) What are adolescent students’ patterns of use of technology tools (search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging)? Our hypothesis was that most adolescents would use the tools analysed, mainly in the home and in most cases for entertainment purposes.

2) Does the use of technology tools in the classroom exert an influence on adolescent students’ academic performance? We hypothesised that the more technology tools (search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging) were used in the classroom, the better the students’ academic performance would be in the four core subjects analysed (mathematics, science, Spanish language, and English); that female students would present better academic performance than male students; and that older adolescents would present the best performance.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample

We surveyed 1.488 students aged between 12 and 18 years old, of which 698 were male and 790 females, distributed evenly between four courses of compulsory secondary education (CSE: 1st year n=397, 2nd year n=403; 3rd year n=324; 4th year n=364). This was a representative sample obtained through the intentional sampling of nine Spanish educational centres attended by students from both rural and urban areas. All these educational centres are located in Castile and Leon.

2.2. Research instrument

A questionnaire was designed, the Hegeco, consisting of three differentiated parts: 1) the first part consisted of three questions about students’ general personal details: age, gender and educational level; 2) the second part included thirty specific questions about use, frequency, time spent, purpose, place of use and levels of satisfaction for five technology tools (search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging),and (iii) the third part consisted of thirty questions about use of these tools in the classroom and about academic performance, the most recent marks in four core subjects of compulsory secondary education (science, mathematics, Spanish language and English). Two identical versions of the questionnaire were designed, an online version (through Google Forms) and a print version to facilitate the collection of data. A principal component analysis (PCA) was run on the questionnaire. The suitability of PCA was assessed prior to analysis. The overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure was 0.883 with individual KMO measures all greater than 0.7, classifications of ‘middling’ to ‘meritorious’ according to Kaiser (1974). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (p<.0005), indicating that the data was factorizable.

PCA revealed twenty-two components that had eigenvalues greater than one and which explained 67,2% of the total variance. Visual inspection of the scree plot indicated that five components should be retained. In addition, a five-component solution met the interpretability criterion. As such, five components were retained.

The five-component solution explained 35.99% of the total variance. The Varimax orthogonal rotation was employed to aid interpretability. The rotated solution exhibited ‘simple structure’ (Thurstone, 1947). The interpretation of the data was consistent with the use of technology tools and academic performance to measure academic success with strong loadings of blogging items, on Component 1 that explained 11,16% of variance, podcasting items on Component 2 which elucidated 9,33% of variance, wikis items on Component 3 that explained 6,60% of variance, instant messaging items on Component 4, which elucidated 4,46% of variance, and academic performance items on Component 5 that explained 4,42% of variance. In addition, the questionnaire had a high level of internal consistency as determined by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.800.

2.3. Procedure

After the questionnaire had been designed, it was validated by five experts from Spanish universities, and its application in educational centres was authorized by General Directorate of Innovation and Educational Equity in Castile and Leon, in accordance with deontological standards for scientific research. Various educational centres (schools and colleges) providing Compulsory Secondary Education were informed about the study. To this end, initial telephone contact was established with the head teachers of the respective centres, and then, prior to administration of the questionnaire, informed consent was sought and obtained from the nine educational participating centres. The instrument was administered in the classrooms during the tutoring period in order to minimize interference with students’ education. For the same reason, questionnaire administration required a maximum of 20 min for each group of students.

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

To answer research question 1, on adolescent students’ patterns of use of technology tools, we analysed descriptive statistics for the variables corresponding to the following items: use, frequency, time spent, purpose, place of use and levels of satisfaction for five technology tools (search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging)

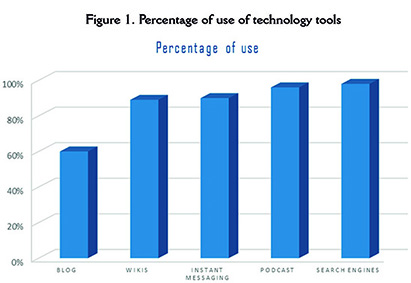

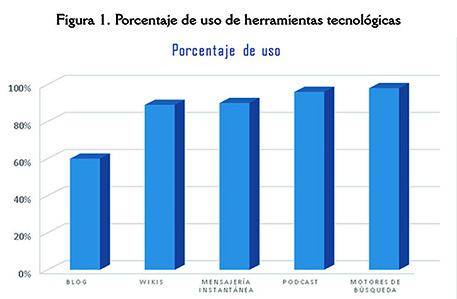

First, in relation to use, as presented in Figure 1, almost all students reported using search engines such as Google or Safari (98%) and instant messaging such as WhatsApp or Telegram (96%), followed by podcast (90%), wikis (89%) and blogs (60%).

In regard to frequency, adolescents stated that they used instant messaging (79%) and podcasts (55%) every day, and search engines (49%) and wikis (34%) several times a week. For time spent, students indicated that they spent between one and three hours a day using tools such as podcasts (45%) and instant messaging (38%), whereas they spent less than one hour a day using other tools such as wikis (67%) and search engines (51%).

With regard to purpose, 86% reported using search engines and wikis to carry out academic homework and tasks [e.g. Fhomework=1293 versus Fsocial interaction=456; p<.001] [e.g. Fhomework=1283 versus Fsocial interaction=26; p<.001]. Meanwhile, 87% reported using podcasts for entertainment [e.g. Fentertainment=1306 versus Fhomework=230; p<.001] and instant messaging to interact with others [e.g. Fsocial interaction=1304 versus Fhomework=321; p<.001].

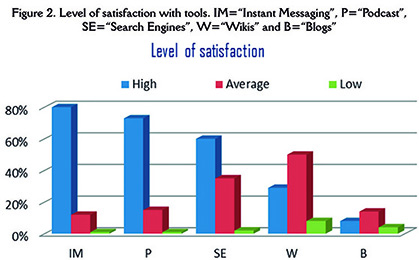

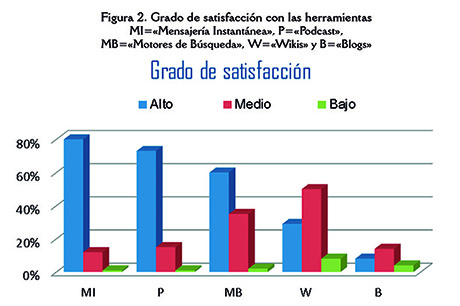

In relation to the place of use, the tools were mainly used in the home. Thus, home was the place where 95% reported using search engines [e.g. Fhome=1413 versus Fschool=388; p<.001], 91% instant messaging [e.g. Fhome=1368 versus Fschool=123; p<.001], 89% podcasts [e.g. Fhome =1328 versus Fschool =99; p<.001] and 84% wikis [e.g. Fhome=1262 versus Fschool=335; p<.001]. Finally, as shown in Figure 2 (next page), students’ level of satisfaction with the tools was high in the case of instant messaging (81.5%), podcasts (73%) and search engines (60%), and average in the case of wikis (50%) and blogs (14%).

3.2. Multivariate Linear Analysis (GLM)

To answer research question 2, on the influence of the use of technology tools on adolescent students’ academic performance, we carried out multivariate analyses where between-subject factors were the questionnaire variables referring to students’ academic performance in four core subjects (science, mathematics, Spanish language, and English) and grouping variables were gender, educational level, age and use of tools.

Application of the GLM revealed statistically significant multivariate contrasts. The Durbin-Watson statistic yielded a value of 1.956 for the independence of residuals. The R2 for the general model was 56.8% with an adjusted R2 of 55.4%, indicating a large effect size when considering gender, age, educational level and use of tools in the subjects, since we obtained statistically significant differences in students’ academic performance (F [41,1224]=39.306, p<0.0005).

Tests for between-subject effects when considering gender, age, educational level and use of tools as grouping variables, yielded statistically significant differences. In addition, a post-hoc analysis and contrast of means for academic performance in the four core subjects (science, mathematics, Spanish language, and English) also evidenced statistically significant differences. Therefore, we obtained statistically significant differences in students’ academic performance in the four subjects analysed, and in performance in the trimester and the previous academic year.

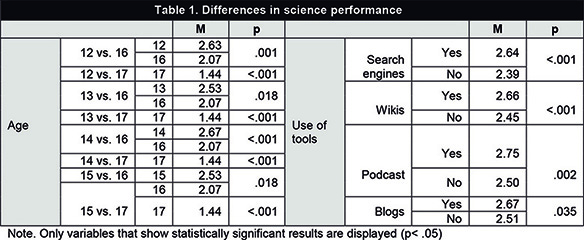

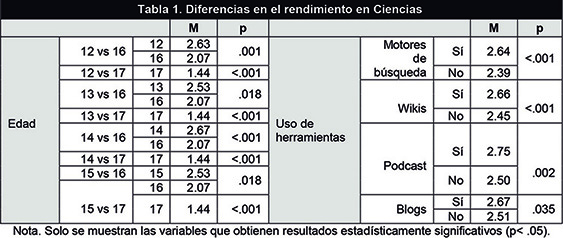

In science, we found statistically significant differences in student performance according to age and use of tools. As it can be seen in Table 1, taking age as the grouping variable, we observed differences in the mark of students aged between 12 and 15 years old and those aged between 16 and 17, in favour of the youngest [e.g., M12yrs=2.63 versus M17yrs=1.44; p<.001]. As regards to the use of tools, we found differences between students who used search engines, wikis, podcasts and blogs on science, and those who did not use them, whereby students who routinely used these tools presented better performance [e.g., MUseOfSearchEngines=2.64 versus MNon-UseOfSearchEngines=2.39; p< .001].

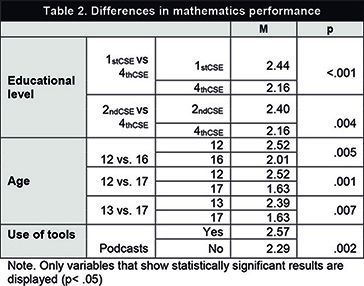

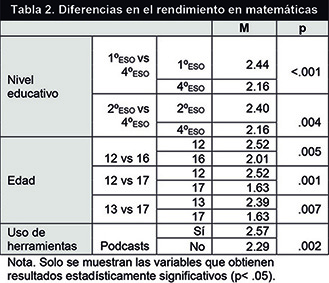

In mathematics, as shown in Table 2, we obtained statistically significant differences in student performance according to educational level, age and use of tools. With regard to educational level, we observed differences between 1st and 2nd-year students and those in their 4th year, in favour of the former [e.g., M1stCSE=2.44 versus M4thCSE=2.16; p<.001]. In addition, for age, we found differences between students aged 12 and 13 years old and those aged 17, in favour of the younger students [e.g., M12yrs=2.52 versus M17yrs=1.63; p=.001]. Lastly, in relation to use of tools, we detected differences in mathematics between students who used podcasts and those who did not, whereby the former presented better performance [e.g., MUseOfPodcasts=2.57 versus MNon-UseOfPodcasts=2.29; p=.002].

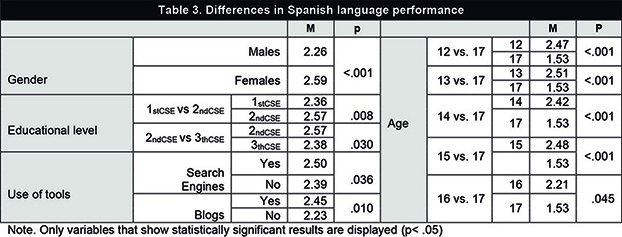

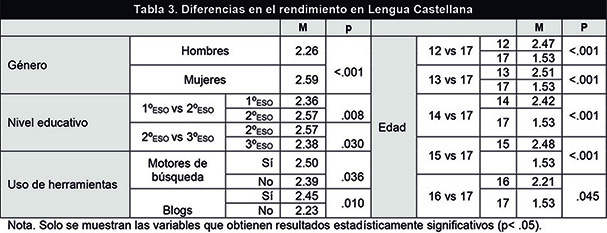

In the Spanish language, we found statistically significant differences in student performance according to the four grouping variables; gender, educational level, age and use of tools, as presented in Table 3. With regard to gender, females presented better performance in this subject [e.g., MFemale=2.59 versus MMale=2.26; p<.001]. In relation to educational level, we observed significant differences in the mark between 2nd-year students and those in the 1st and third years, in favour of the former [e.g., M2ndCSE=2.57 versus M1stCSE= 2.36; p=.008]. Regarding age, we found differences between students aged between 12 and 16 years old and those aged 17, in favour of the former [e.g., M12yrs=2.47 versus M17yrs=1.53; p<.001].

Lastly, in relation to the use of tools, we detected differences in student performance between those who used search engines and those who did not, in favour of the former [e.g., MUseOfSearchEngines=2.50 versus MNon-UseOfSearchEngines=2.39; p=.036] and between students who used blogs on this subject and those who did not, whereby the former presented better performance [e.g., MUseOfBlogs=2.45 versus MNonUseOfBogs=2.23; p=.010].

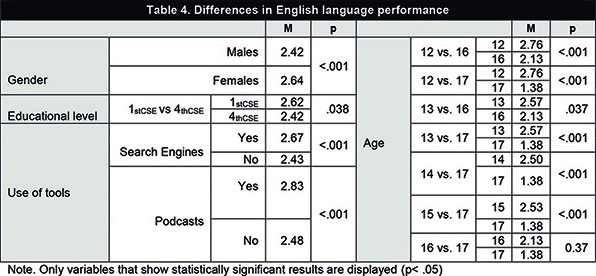

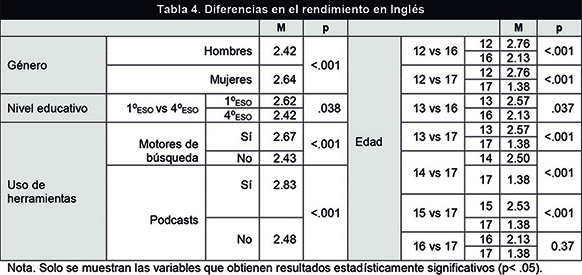

In the English language, as shown in Table 4 (next page) we obtained statistically significant differences in student performance according to all four grouping variables. In relation to gender, females displayed better mean performance [e.g. MFemale=2.64 versus MMale= 2.42; p<.001]. As regards to educational level, we observed significant differences in the mark between 1st year students and those in the 4th year, in favour of the former [e.g., M1stCSE=2.62 versus M4thCSE=2.42; p=.038]. Regarding age, we detected differences between students aged 12 to 16 years old and those aged 17, and between students aged 12 and 13 years old and those aged 16, in all cases in favour of the younger students [e.g., M12yrs=2.76 versus M17yrs=1.38; p<.001].

In regard to the use of tools, we found differences between students who used search engines in this subject and those who did not, and between those who used podcasts and those who did not. In both cases, students using these technologies in the subject presented better performance [e.g. MUseOfPodcasts=2.83 versus MNon-UseOfPodcasts=2.48; p<.001].

In relation to the performance of students in all subjects in the previous trimester, statistically, significant differences were observed according to gender and age. As regards to gender, females obtained a better mean mark [e.g., MFemale=2.60 versus MMale=2.37; p<.001], while for age, we found differences between students aged 12 to 15 years old and those aged 17, whereby the younger students presented better performance [e.g., M12yrs=2.63 versus M17yrs=1.53; p<.001].

In relation to the performance of students in all subjects in the previous academic year, statistically, significant differences were observed according to all four grouping variables. As regards to gender, females obtained a better mark [e.g., MFemale=2.86 versus MMale=2.66; p<.001]. For educational level, we observed significant differences between 1st and 2nd-year students, in favour of the former [e.g., M1stCSE=2.86 versus M2ndCSE=2.69; p=.050].

Turning to age, we obtained differences between students of all ages except those aged 16, whereby the youngest students achieved the highest mean mark [e.g., M12yrs=3.01 versus M17yrs=2.00; p<.001].

Lastly, in relation to use of tools, we detected differences in student performance between those who used wikis and those who did not, in favour of the former [e.g., MUseOfWikis=2.79 versus MNon-UseOfWikis=2.62; p=.016] and between those who used blogs and those who did not, in favour of the latter [e.g., MNon-UseOfBlogs=2.80 versus MUseOfBlogs=2.75; p<.001].

4. Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this study was to analyse adolescent students’ use of five technologies (search engines, wikis, blogs, podcasts and instant messaging) and determine the impact of such use on their academic performance in four core subjects (science, mathematics, Spanish language, and English).

First, our results indicate that these adolescents knew about and used all the tools analysed. Nine out of ten students aged between 12 and 18 years old conducted Internet searches, viewed or shared audio and video files, consulted information on wikis and used instant messaging applications. This evidences that young people today make heavy use of such technologies, in agreement with the results obtained in various other studies (Gross, Juvonen, & Gable, 2002; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). We also found that our subjects mainly used these technologies in the home. Thus, although increasing use is made of technology tools in the classroom, there is still a clear tendency to use them outside of the school context.

In addition, a detailed analysis of questionnaire responses revealed differential patterns in the use of technologies according to purpose. Adolescents used tools such as search engines and wikis to do homework and academic tasks, podcasts for entertainment and instant messaging to interact with others. Therefore, they consciously selected tools depending on the purpose, which may be due to the broad functional knowledge that young people have of these tools (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2013).

Second, in relation to the positive influence on academic performance exerted by use in the classroom of the five technology tools examined, it should be noted that our results revealed differential patterns in performance according to the variables gender, age and use of tools.

Females presented significantly better mean performance than males in the linguistic subjects of Spanish language and English. These results coincide with those reported in several other studies (Cerezo & Casanova, 2004; Costa & Tabernero, 2012; Sheard, 2009), and may be due to stronger development of communication skills in females. Meanwhile, younger adolescents aged 12 and 13 years old presented better performance in all four areas (science, mathematics, Spanish language, and English), in contrast with the results reported in other studies indicating that older adolescent students display the best performance (Sheard, 2009). The results obtained can be explained by the existence of a higher number of students aged 14 to 18 who were repeating a year.

Lastly, this study indicates that use of technology tools in the classroom significantly affects adolescent students’ performance in the subjects analysed (science, mathematics, Spanish language, and English), exerting a positive influence on science, Spanish language, and English and a negative one on mathematics. In this respect, students who used search engines presented significantly better performance in Science, Spanish language and English. Meanwhile, in mathematics, students who did not use any technology tool in the classroom, except podcasts, presented significantly better performance. These results partially coincide with those obtained in other studies indicating that use of the same technology tool in education can have a positive impact in some areas and a negative one in others (Antonijevic, 2007; Torres-Díaz, Duart, Gómez-Alvarado, Marín-Gutiérrez, & Segarra-Faggioni, 2016).

Our results add to the literature on the use of technologies and academic performance and represent the first step in research on the academic effects on adolescent students of the use of various technology tools. The present study has significant implications for the use of technologies in the classroom, as it is important that teachers know when and why young people use technologies, which ones they use and which ones exert positive influences on adolescent students’ academic performance when used in the classroom.

Teachers must carefully select technology tools according to the subjects to address because it has been shown that writing, publishing and reading blog content is an effective means to teach and learn one’s native language. Similarly, information searches, translations and listening to or viewing audio and video files are useful for teaching and learning a foreign language.

However, this study presents some limitations. This was a cross-sectional study since data were collected in a single moment in time. It would be desirable to conduct longitudinal research to understand students’ academic performance throughout the entire secondary stage. In addition, besides self-report data from students, future research should include other measures of the use of technologies and academic performance when possible. It would also be useful to conduct more studies on the way in which use of other technology tools can enhance academic performance. The ultimate aim of such research would be to provide a quality education for adolescent students.

Funding Agency

This work was supported by the University of León (Spain) for 2016-2020.

References

Antonijevic, R. (2007). Usage of computers and calculators and students’ achievement: Results from TIMSS 2003. International Conference on Informatics, Educational Technology and New Media in Education, Sombor, Serbia. https://bit.ly/2A4HiQT

BOCYl (Ed.) (2015). Orden Edu/336/2015, de 27 de abril, por la que se regula el procedimiento para la obtención de la certificación en la aplicación de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación, por los centros docentes no universitarios, Valladolid, 2015-06-05 n. 84, 30622. https://bit.ly/2zzGsuZ

Cerezo, M.T., & Casanova, P.F. (2004). Diferencias de género en la motivación académica de los alumnos de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 2(3), 97-112. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.3.125

Cetinkaya, L. (2017). The impact of WhatsApp use on success in education process. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7), 59-74. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.3279

Costa, S., & Tabernero, C. (2012). Rendimiento académico y autoconcepto en estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria según el género. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 2012, 3(2), 175-193. https://bit.ly/2ranaYF

Duart, J.M., Gil, M., Pujol, M., & Castaño, J. (2008). La universidad en la sociedad Red. Usos de la Internet en Educación Superior. Barcelona: Ariel.

García-Martín, J., & García-Sánchez, J.N. (2013). Patterns of Web 2.0 tool use among young Spanish people. Computers & Education, 67, 105-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.03.003

Gil, J. (2012). Utilización del ordenador y rendimiento académico entre los estudiantes españoles de 15 años. Revista de Educación, 357, 375-396. https://bit.ly/2U8VuAB

Gross, E.F., Juvonen, J., & Gable, S.L. (2002). Internet use and well-being in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 75-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00249

Han, I., & Shin, W.S. (2016). The use of a mobile learning management system and academic achievement of online students. Computers & Education, 102, 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.07.003

Jonassen, D.H., & Kwon, H. (2001). Communication patterns in computer mediated versus face-to-face group problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(1), 35-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02504505

Junco, R. (2015). Student class standing, Facebook use, and academic performance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 18-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.001

Kaiser, H.F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 32-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

Montes-Vozmediano, M., García-Jiménez, A., & Menor-Sendra, J. (2018). Teen videos on YouTube: Features and digital vulnerabilities. [Los vídeos de los adolescentes en YouTube: Características y vulnerabilidades digitales]. Comunicar, 54(26), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-06

Ndege, W., Mutavi, T., Kokonya, D., Nekesa, V., Musungu, B., Obondo, A., & Wangari, M. (2015). Social networks and students’ performance in secondary schools: Lessons form an Open Learning Centre, Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(21), 171-178. https://bit.ly/2DPqvDW

Noshahr, R., Talebi, B., & Mojallal, M. (2014). The relationship between use of cell-phone with academic achievement in female students. Applied Mathematics in Engineering, Management and Technology, 2(2), 424-428. https://bit.ly/2EiKmvB

Pantoja, A., & Huertas, A. (2010). Integración de las TIC en la asignatura de Tecnología de Educación Secundaria. Pixel-Bit, 37, 225-237. https://bit.ly/2P8klR7

Risso, A., Peralbo, M., & Barca, A. (2010). Cambios en las variables predictoras del rendimiento escolar en Enseñanza Secundaria. Psicothema, 22(4), 790-796. https://bit.ly/2Sglpob

Sheard, M. (2009). Hardiness commitment, gender, and age differentiate university academic performance. British Journal of Educational Society, 79, 189-204. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X304406

Soler-Adillon, J., Pavlovic, D., & Freixa, P. (2018). Wikipedia in higher education: Changes in perceived value through content contribution. [Wikipedia en la Universidad: Cambios en la percepción del valor con la creación de contenidos]. Comunicar, 54(26), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-04

Tabatabai, D., & Shore, B.M. (2005). How experts and novices search the Web. Library & Information Science Research, 27(2), 222-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.005

Thurstone, L.L. (1947). Multiple factor analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Torres-Díaz, J.C., Duart, J.M., Gómez-Alvarado, H.F., Marín-Gutiérrez, I., & Segarra-Faggioni, V. (2016). Internet use and academic success in university students. Usos de Internet y éxito educativo en estudiantes universitarios]. Comunicar, 48(24), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-06

Valkenburg, P.M., & Peter, J. (2007). Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Developmental Psychology, 43, 267-277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267

Wentwoth, D.K., & Middleton, J.H. (2014). Technology use and academic performance. Computers & Education, 78, 306-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.012

Wittwer, J., & Senkbeil, M. (2008). Is students’ computer use at home related to their mathematical performance at school? Computers & Education, 50, 1558-1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.03.001

Yuen, S.C., & Yuen, P.K. (2010). What teachers think about Web 2.0 technologies in education? 16th Annual Sloan Consortium International Conference Online Learning. Orlando, Florida. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.03.001

Click to see the English version (EN)

Resumen

Las tecnologías han adquirido una importancia estratégica, llegándose a definir como herramientas educativas sin precedentes. En este estudio se analiza el uso que 1.488 adolescentes españoles hacen de cinco herramientas; motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcast y mensajería instantánea, y se estudia el impacto de dicho uso en su rendimiento académico en Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés. Para ello, se explora la frecuencia de uso, el tiempo dedicado, la finalidad, el lugar de uso y el grado de satisfacción con cada herramienta, así como los logros académicos obtenidos en las cuatro asignaturas analizadas, a través del instrumento HEGECO. Los resultados muestran patrones diferenciales en el uso de las tecnologías en función de la finalidad y en el rendimiento académico en función del sexo, de la edad y del uso de herramientas. Los adolescentes utilizan herramientas como motores de búsqueda y wikis para realizar tareas académicas y el podcast para divertirse. Relativo al rendimiento académico, las mujeres presentan un rendimiento promedio superior en las áreas lingüísticas, así como los adolescentes más jóvenes en todas las asignaturas analizadas. En función del uso de herramientas, el uso de motores de búsqueda se relaciona con un mayor rendimiento en Ciencias y en las áreas lingüísticas y el uso de podcast con un mayor rendimiento en Matemáticas. En este sentido, y a la luz de los resultados se discuten y se valoran las implicaciones.

1. Introducción

Las Tecnologías del Aprendizaje y el Conocimiento han sido definidas como «herramientas educativas sin precedentes» (Pantoja & Huertas, 2010: 225). Estas tecnologías abarcan los motores de búsqueda, las wikis, los blogs, la mensajería instantánea y los podcasts o archivos de audio y video que permiten a los usuarios crear, colaborar, conectar, compartir y participar en una comunidad de aprendizaje (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2013; Yuen & Yuen, 2010).

Los últimos años han sido testigos de la constante incorporación de las tecnologías en las escuelas (Bocyl, 2015). Por tanto, las variables que tradicionalmente se han relacionado con el rendimiento académico ahora deben ampliarse para incluir las tecnologías, especialmente aquellas que se corresponden con el entorno tecnológico institucional, la accesibilidad y el uso de Internet. Estas herramientas son entendidas como nuevos determinantes del rendimiento académico ya que inciden en el trabajo del estudiante a distintos niveles y de diferentes formas (Duart, Gil, Pujol, & Castaño, 2008; Han & Shin, 2016; Torres-Díaz, Duart, Gómez-Alvarado, Marín-Gutiérrez, & Segarra-Faggioni, 2016).

Diversos autores han examinado el uso que los jóvenes hacen de las tecnologías y el impacto de algunas de estas herramientas en su rendimiento académico (Junco, 2015; Noshahr, Talebi &, Mojallal, 2014; Wentworth & Middleton, 2014). Herramientas como las wikis son un recurso muy utilizado por parte de los adolescentes (Soler-Adillon, Pavlovic, & Freixa, 2018) así como, la mensajería instantánea que, al facilitar la comunicación directa e individualizada, incrementa la confianza y la sensación de intimidad entre los jóvenes (Cetinkaya, 2017; Noshahr, Talebi, & Mojallal, 2014). Además, la búsqueda de información en Internet implica seleccionar fuentes adecuadas, y posteriormente, extraer, organizar e integrar la información obtenida, ayudando a los estudiantes a adquirir habilidades para la resolución de problemas. Así como, la participación en chats mejora las habilidades de comunicación y de interacción (Jonassen & Kwon, 2001; Ndege, & al., 2015; Tabatabai & Shore, 2005). Apoyando estas afirmaciones, los resultados de diversos estudios muestran que, tanto el uso del ordenador como el tipo de actividad realizada contribuyen significativamente a explicar, no solo el rendimiento académico en los jóvenes, sino también el mayor éxito académico en educación superior alcanzado por aquellos que hacen un uso equilibrado de las tecnologías (Gil, 2012; Torres-Díaz & al., 2016).

Al mismo tiempo y en sentido opuesto a estos hallazgos, otras investigaciones han afirmado que no existe relación entre el rendimiento académico y el uso y el acceso a las tecnologías en la educación, al no hallarse una correlación significativa entre las calificaciones escolares y el tiempo que los estudiantes dedican al uso de las tecnologías (Noshahr, Talebi, & Mojallal, 2014). También exponen que el uso de las tecnologías puede afectar al desempeño de los estudiantes en un área concreta pero no en otras; encontrándose, por ejemplo, que el uso de los ordenadores en la enseñanza no contribuye significativamente a mejorar el rendimiento de los estudiantes en Matemáticas, pero sí en Ciencias (Antonijevic, 2007; Wittwer & Senkbeil, 2008).

La investigación, por tanto, ha arrojado resultados contradictorios, lo que subraya la necesidad de desarrollar nuevos estudios en los que se analicen los patrones de uso de las tecnologías por parte de los estudiantes. Además, es necesario conocer el uso que se hace de estas herramientas en los centros educativos y su influencia en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes durante la adolescencia; una etapa caracterizada por cambios psicosociales y cognitivos que están viéndose afectados por el aumento exponencial del uso de las tecnologías (Montes-Vozmediano, García-Jiménez, & Menor-Sendra, 2018; Risso, Peralbo, & Barca, 2010). En este sentido, el propósito de este estudio fue analizar el uso que los estudiantes adolescentes hacían de cinco tecnologías y conocer el impacto de dicho uso en su rendimiento académico.

1.1. Preguntas de investigación

Con el fin de examinar si el uso de las tecnologías influye en el rendimiento y en el logro escolar de los estudiantes adolescentes, en este estudio se investigó: (i) el uso que los estudiantes adolescentes hacen de cinco herramientas tecnológicas (motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcasts y mensajería instantánea) y (ii) el impacto que tiene el uso de estas herramientas en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes adolescentes.

Se formularon, por tanto, las siguientes preguntas de investigación:

1) ¿Cuáles son los patrones de uso de las herramientas tecnológicas (motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcasts y mensajería instantánea) por parte de los estudiantes adolescentes? Se partió de la hipótesis de que la mayoría de los adolescentes utilizaban las herramientas analizadas, principalmente en el hogar y en la mayoría de los casos con el propósito de entretenerse.

2) ¿El uso de las herramientas tecnológicas en el aula influye en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes adolescentes? Se hipotetizó que a mayor uso de las herramientas tecnológicas (motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcasts y mensajería instantánea) en las aulas, mayor rendimiento académico de los estudiantes en las cuatro asignaturas analizadas (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés); que las estudiantes mujeres presentaban mayor rendimiento académico que los estudiantes varones, y que los adolescentes de mayor edad eran los que mejor rendimiento presentaban.

2. Material y métodos

2.1. Muestra

Se encuestaron a 1.488 estudiantes de edades comprendidas entre los 12 y los 18 años, de los cuales 698 eran hombres y 790 mujeres, distribuidos uniformemente entre los cuatro cursos de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO: 1º curso n=397; 2º curso n=403; 3º curso n=324; 4º curso n=364). Esta fue una muestra representativa obtenida, a través de un muestreo intencional, de nueve centros educativos españoles que atendían a estudiantes de zonas rurales y urbanas. Todos los centros educativos pertenecían a la Comunidad de Castilla y León.

2.2. Instrumento de investigación

Se diseñó un cuestionario, HEGECO, que constaba de tres partes diferenciadas: 1) La primera parte consistía en tres preguntas sobre datos generales de los estudiantes: edad, género y curso o nivel educativo; 2) la segunda parte incluía treinta preguntas sobre el uso, la frecuencia, el tiempo dedicado, la finalidad, el lugar de uso y el grado de satisfacción con cinco herramientas tecnológicas (motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcasts y mensajería instantánea); 3) La tercera parte constaba de treinta preguntas sobre el uso de estas herramientas en las aulas y sobre el rendimiento académico, medido éste mediante las últimas calificaciones en cuatro asignaturas obligatorias de la etapa secundaria (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés). Se elaboraron dos versiones idénticas del cuestionario, una versión online (a través de Formularios de Google) y otra, impresa para facilitar la recogida de los datos.

Se realizó un Análisis de Componentes Principales (ACP) en el cuestionario. La idoneidad del análisis de componentes principales se evaluó previamente. La medida general de Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) fue de 0.883 con medidas individuales de KMO todas superiores a 0.7, clasificaciones de «media» a «meritoria» según Kaiser (1974). Asimismo, la prueba de esfericidad de Bartlett fue estadísticamente significativa (p<.0005), lo que indica que los datos eran factorizables.

El análisis de componentes principales reveló veintidós componentes que tenían valores propios mayores que uno y que explicaban el 67,2% de la varianza total. La inspección visual del gráfico de dispersión indicó que debían retenerse cinco componentes. Además, la solución de cinco componentes cumplía con el criterio de interpretabilidad, por lo que se les retuvieron.

La solución de cinco componentes principales explicó el 35,99% de la varianza total. Se empleó una rotación ortogonal Varimax para ayudar a la interpretabilidad. La solución rotada mostraba una «estructura simple» (Thurstone, 1947). La interpretación de los datos fue consistente con el uso de herramientas tecnológicas y el rendimiento académico para medir el éxito escolar con fuertes cargas de elementos de blog en el Componente 1 que explicaban el 11,16% de la varianza, elementos de podcast en el Componente 2 que revelaban el 9,33% de la varianza, elementos de wikis en el Componente 3 que explicaban el 6,6% de la varianza, ítems de mensajería instantánea en el Componente 4 que clarificaban el 4,46% de la varianza e ítems de rendimiento académico en el Componente 5 que explicaron el 4,42% de la varianza. Además, el cuestionario mostró un alto nivel de consistencia interna determinado por un alfa de Cronbach de 0.8.

2.3. Procedimiento

Una vez se diseñó el cuestionario, éste fue validado por cinco expertos de universidades españolas y su aplicación en centros educativos fue autorizada por la Dirección General de Innovación y Equidad Educativa en Castilla y León, de conformidad con las normas deontológicas para la investigación científica. Varios centros educativos (colegios e institutos) que impartían Educación Secundaria Obligatoria fueron informados del estudio e invitados a participar. Para lo cual, se estableció contacto telefónico inicial con los directores de los centros, y posteriormente, antes de la aplicación del cuestionario, se solicitó consentimiento informado de los nueve centros educativos participantes. El instrumento fue aplicado en las aulas durante las tutorías para interferir lo menos posible en el proceso educativo de los estudiantes. Por la misma razón, la aplicación del cuestionario requirió de un máximo de veinte minutos por cada grupo de estudiantes.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1. Análisis descriptivo

Para responder a la pregunta de investigación 1, relativa a los patrones de uso de las herramientas tecnológicas por parte de los estudiantes adolescentes, se analizaron estadísticos descriptivos para las variables correspondientes a los ítems: uso, frecuencia, tiempo, finalidad, lugar de uso y grado de satisfacción con cinco herramientas tecnológicas (motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcasts y mensajería instantánea).

En primer lugar, en relación al uso, como se presenta en la Figura 1, casi todos los estudiantes afirmaron utilizar motores de búsqueda como Google o Safari (98%) y mensajería instantánea como WhatsApp o Telegram (96%), seguido de los podcasts (90%), de las wikis (89%) y de los blogs (60%).

En relación a la frecuencia, los adolescentes afirmaron usar mensajería instantánea (79%) y podcasts (55%) todos los días, mientras que los motores de búsqueda (49%) y las wikis (34%) varias veces a la semana.

Relativo al tiempo de uso, los estudiantes indicaron que dedicaban entre una y tres horas diarias a utilizar herramientas como podcasts (45%) y mensajería instantánea (38%), mientras que al uso de otras herramientas como wikis (67%) y motores de búsqueda (51%) dedicaban menos de una hora al día.

En relación a la finalidad, el 86% de los estudiantes afirmó utilizar los motores de búsqueda y las wikis para realizar deberes y trabajos académicos [Fdeberes=1293 frente a Frelacionarse =456; p<.001] [Fdeberes=1283 frente a Frelacionarse=26; p<.001] respectivamente. Al mismo tiempo, el 87% informó que utilizaba el podcast para entretenerse [ej. Fentretenimiento=1306 frente a Fdeberes=230; p<.001] y la mensajería instantánea para relacionarse con los demás [ej. Frelacionarse=1304 frente a Fdeberes=321; p<.001].

Respecto al lugar de uso, las herramientas eran utilizadas preferentemente en el hogar. En este sentido, el 95% aseguró utilizar motores de búsqueda [ej. Fhogar=1413 frente a Fescuela=388; p<.001], el 91%, mensajería instantánea [ej. Fhogar=1368 frente a Fescuela=123; p<.001], el 89%, podcasts [ej. Fhogar=1328 frente a Fescuela=99; p<.001] y el 84%, wikis [ej. Fhogar= 1262 frente a Fescuela=335; p<.001]. Finalmente, como se muestra en la Figura 2, el grado de satisfacción de los estudiantes con las herramientas era alto en el caso de la mensajería instantánea (81%), de los podcasts (73%) y de los motores de búsqueda (60%), y medio en el caso de las wikis (50%) y de los blogs (14%).

3.2. Análisis lineal multivariado

Para responder a la pregunta de investigación 2, relativa a la influencia que tiene el uso de las herramientas tecnológicas en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes adolescentes, se realizaron análisis multivariados tomando como factores inter-sujetos las variables del cuestionario que hacen referencia al rendimiento académico de los estudiantes en cuatro asignaturas (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés) y como variables de agrupamiento: el género, el nivel educativo, la edad y el uso de herramientas.

La aplicación del análisis lineal multivariado reveló contrastes multivariados, estadísticamente significativos, y la estadística de Durbin-Watson arrojó un valor de 1.956 sobre la independencia de residuos. Además, R2 para el modelo general fue de 56,8% con un R2 ajustado de 55.4%, lo que implica un gran tamaño del efecto (Cohen, 1988) cuando se consideran el género, la edad, el nivel educativo y el uso de herramientas en las asignaturas, pues se obtienen diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes (F [41,1224]=39.306, p<0.0005).

Las pruebas de efectos inter-sujetos, cuando se consideraron el género, la edad, el nivel educativo y el uso de herramientas como variables de agrupamiento, arrojaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas. Además, en el examen de los análisis post-hoc y en la confrontación de medias del rendimiento académico en las cuatro asignaturas (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés) también se evidenciaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas. Por lo tanto, se obtuvieron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes en las cuatro asignaturas analizadas y en el rendimiento promedio en el trimestre y en el curso académico anteriores.

En Ciencias, se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el rendimiento de los estudiantes atendiendo a la edad y al uso de herramientas. Como puede verse en la Tabla 1, teniendo en cuenta la edad como variable de agrupamiento, se mostraron diferencias en la nota media de los alumnos de entre 12 y 15 años, y los de 16 y 17, en favor de los más jóvenes [ej., M12años=2.63 frente a M17años =1.44; p< .001]. Asimismo, atendiendo al uso de herramientas, se observaron diferencias entre los alumnos que usaban motores de búsqueda, wikis, podcasts y blogs en Ciencias, y aquellos que no las utilizaban, mostrando un mayor rendimiento en esta asignatura los alumnos que usaban estas herramientas de forma habitual [ej. MUsoMotoresDeBúsqueda=2.64 frente a MNo-UsoMotoresDeBúsqueda=2.39; p< .001].

En Matemáticas, como se muestra en la Tabla 2, se obtuvieron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el rendimiento de los estudiantes, atendiendo al nivel educativo, a la edad y al uso de herramientas. Teniendo en cuenta el nivel educativo, se observaron diferencias entre los alumnos de 1º y 2º curso y los alumnos de 4º curso, en favor de los estudiantes de los primeros cursos [ej. M1ºESO=2.44 frente a M4ºESO=2.16; p<.001].

Además, atendiendo a la edad se encontraron diferencias entre los alumnos de 12 y 13 años con los de 17, a favor de los alumnos más jóvenes [ej. M12años=2.52 frente a M17años=1.63; p=.001]. Finalmente, atendiendo al uso de herramientas, se detectaron diferencias en el rendimiento en matemáticas entre los estudiantes que usaban podcasts y los que no utilizaban dicha herramienta, siendo el rendimiento mayor en los primeros [ej. MUsoDePodcasts=2.57 frente a MNo-UsoDePodcasts=2.29; p=.002].

En Lengua Castellana, se revelaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el rendimiento de los estudiantes teniendo en cuenta las cuatro variables de agrupamiento; el género, el nivel educativo, la edad y el uso de herramientas, como se presenta en la Tabla 3. Atendiendo al género, eran las mujeres las que presentaban mayor rendimiento en esta asignatura [ej. MMujer= 2.59 frente a MHombre=2.26; p<.001].

En relación al nivel educativo, se encontraron diferencias significativas en la nota media de los alumnos de 2º curso con los de 1º y 3º, en favor de los alumnos de segundo curso [ej. M2ºESO=2.57 frente a M1ºESO=2.36; p=.008]. Teniendo en cuenta la edad, se obtuvieron diferencias en los alumnos de entre 12 y 16 años y los de 17, en favor de los primeros [ej. M12años=2.47 frente a M17años=1.53; p<.001]. Finalmente, atendiendo al uso de herramientas, se detectaron diferencias en el rendimiento académico de los alumnos que sí utilizaban motores de búsqueda y los que no, a favor de los primeros [ej. MUsoDeMotoresBúsqueda=2.50 frente a MNo-UsoMotoresBúsqueda=2.39; p=.036] y entre los alumnos que sí utilizaban blogs en dicha asignatura y los que no, siendo el rendimiento mayor en los primeros [ej. MUsoDeBlogs=2.45 frente a MNo-UsoDeBlogs=2.23; p=.010].

En Inglés, como se muestra en la Tabla 4, se obtuvieron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el rendimiento de los estudiantes atendiendo a las cuatro variables de agrupamiento. Teniendo en cuenta el género, las mujeres presentaron mayor rendimiento promedio [ej. MMujer=2.64 frente a MHombre=2.42; p<.001]. Atendiendo al nivel educativo se encontraron diferencias en la nota media de los alumnos de 1º curso y los de 4º curso, en favor de los primeros [ej. M1º ESO=2.62 frente a M4º ESO= 2.42; p=.038]. Teniendo en cuenta la edad, se observaron diferencias en los alumnos de entre 12 y 16 años y los de 17 años, así como entre los alumnos de 12 y 13 años y los de 16, en todos los casos, a favor de los estudiantes más jóvenes [ej. M12años=2.76 frente a M17años=1.38; p<.001].

Asimismo, en cuanto al uso de herramientas, se encontraron diferencias entre los alumnos que utilizaban motores de búsqueda en esta asignatura y los que no, y entre los que usaban podcasts y los que no. En ambos casos, el rendimiento era mayor en aquellos alumnos que hacían uso de dichas tecnologías en la materia [ej. MUsoDePodcasts=2.83 frente a MNo-UsoDePodcasts=2.48; p<.001].

En relación al rendimiento promedio de los estudiantes en todas las asignaturas en el trimestre anterior, se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas atendiendo al género y a la edad. Teniendo en cuenta el género, las mujeres eran las que presentaban mayor nota media [ej. MMujer=2.60 frente a MHombre=2.37; p<.001], y atendiendo a la edad, se observaron diferencias entre los alumnos de entre 12 y 15 años y los de 17, siendo el rendimiento mayor en los alumnos más jóvenes [ej. M12años=2.63 frente a M17años=1.53; p<.001].

En relación al rendimiento promedio de los estudiantes en todas las asignaturas del curso académico anterior, se evidenciaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas atendiendo a las cuatro variables de agrupamiento. Teniendo en cuenta el género, las mujeres presentaban mayor nota media [ej. MMujer=2.86 frente a MHombre=2.66; p<.001]. Atendiendo al nivel educativo, se observaron diferencias significativas entre los alumnos de 1º y 2º curso, en favor de los primeros [ej. M1ºESO=2.86 frente a M2ºESO=2.69; p=.050]. Tomando en cuenta la edad, se obtuvieron diferencias entre los alumnos de todas las edades excepto en los de 16 años, siendo los alumnos más jóvenes los que mayor nota media tenían [ej. M12años=3.01 frente a M17años=2.00; p<.001].

Finalmente, atendiendo al uso de herramientas, se detectaron diferencias en el rendimiento de los estudiantes entre los que sí utilizaban wikis y los que no, en favor de los primeros [ej. MUsoDeWikis=2.79 frente a MNo-UsoDeWikis=2.62; p=.016], y entre los que utilizaban blogs y los que no, en favor de estos últimos [ej. MNo-UsoDeBlogs=2.80 frente a MUsoDeBlogs=2.75; p<.001].

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El propósito de este estudio fue analizar el uso que los jóvenes hacen de cinco tecnologías (motores de búsqueda, wikis, blogs, podcasts y mensajería instantánea) y conocer el impacto de dicho uso en su rendimiento académico en cuatro asignaturas troncales (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés).

En primer lugar, los resultados obtenidos indicaron que los adolescentes conocían y utilizaban todas las herramientas analizadas. En esta línea, nueve de cada diez estudiantes de entre 12 y 18 años realizaban búsquedas en Internet, visualizaban y/o compartían archivos de audio y video, consultaban información en wikis y utilizaban aplicaciones de mensajería instantánea. Se evidencia, por tanto, que los jóvenes de hoy en día utilizan las tecnologías en gran medida, lo que coincide con los resultados obtenidos en diversos estudios (Gross, Juvonen, & Gable, 2002; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007). Se confirmó también, que los adolescentes utilizaban estas tecnologías, principalmente, en el hogar. Por tanto, aunque el uso de las herramientas tecnológicas en las aulas haya aumentado, sigue existiendo una clara tendencia a usarlas fuera del contexto educativo.

Además, el análisis detenido de las respuestas del cuestionario reveló patrones diferenciales respecto al uso de las tecnologías teniendo en cuenta la finalidad. Los adolescentes utilizaban herramientas como los motores de búsqueda y las wikis para realizar deberes y trabajos académicos, los podcasts para divertirse y la mensajería instantánea para relacionarse con otros. Por tanto, los adolescentes seleccionaban de forma consciente las herramientas en función de su propósito, lo cual puede deberse al amplio conocimiento funcional que los jóvenes tienen de estas herramientas (García-Martín & García-Sánchez, 2013).

En segundo lugar, en relación al rendimiento académico y a la influencia que ejerce sobre éste el uso de las cinco herramientas tecnológicas analizadas, en las aulas, es preciso destacar que los resultados obtenidos evidenciaron patrones diferenciales en el rendimiento promedio teniendo en cuenta las variables género, edad y uso de herramientas.

Los resultados mostraron un rendimiento promedio significativamente superior en el ámbito lingüístico, en las asignaturas de Lengua Castellana e Inglés, de las mujeres frente a los hombres. Estos resultados que coinciden con los obtenidos en varias investigaciones (Cerezo & Casanova, 2004; Costa & Tabernero, 2012; Sheard, 2009) pueden deberse al mayor desarrollo de las habilidades comunicativas en las mujeres.

Además, los adolescentes más jóvenes, de doce y trece años, presentaron un rendimiento superior en las cuatro asignaturas (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés), discordando con los resultados de otras investigaciones que aseveran que los estudiantes más mayores son los que tienen mejor rendimiento (Sheard, 2009). Los resultados obtenidos pueden explicarse por la existencia de un mayor número de alumnos de entre catorce y dieciocho años que repiten curso.

Finalmente, este estudio pone de manifiesto que el uso de las herramientas tecnológicas en las aulas afecta de forma significativa al rendimiento de los estudiantes adolescentes en las asignaturas analizadas (Ciencias, Matemáticas, Lengua Castellana e Inglés), ejerciendo una influencia positiva en las áreas de Ciencias, Lengua Castellana e Inglés, y negativa en el área de Matemáticas. En este sentido, los alumnos que usaban motores de búsqueda presentaban un rendimiento significativamente superior en Ciencias, Lengua Castellana e Inglés. Sin embargo, en Matemáticas los alumnos que no usaban ninguna de estas herramientas tecnológicas en el aula, excepto los podcasts, presentaban un rendimiento superior. Estos resultados coinciden parcialmente con los obtenidos en otros estudios que ponen de manifiesto que el uso de la misma herramienta tecnológica en el aprendizaje puede tener un impacto positivo en algunas áreas y negativo en otras (Antonijevic, 2007; Torres-Díaz, Duart, Gómez-Alvarado, Marín-Gutiérrez, & Segarra-Faggioni, 2016).

Los hallazgos de nuestro estudio contribuyen a incrementar la literatura existente sobre el uso de las tecnologías y el rendimiento académico, y suponen un primer paso en la investigación sobre los efectos académicos que tiene el uso de varias herramientas tecnológicas en los estudiantes adolescentes. El presente estudio tiene implicaciones significativas en el adecuado uso de las tecnologías en las aulas, ya que es importante que los docentes conozcan qué, cuándo y para qué los jóvenes utilizan las tecnologías y cuáles de dichas herramientas ejercen influencias positivas en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes adolescentes cuando son utilizadas en las aulas.

Los docentes deben seleccionar cuidadosamente las herramientas tecnológicas en función de las áreas que van a trabajar, ya que se ha evidenciado que la elaboración, la publicación y la lectura de contenido en blogs es efectiva para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de la propia lengua. Asimismo, las búsquedas de información, las traducciones y la visualización de archivos de audio y video son útiles para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de un idioma extranjero.

Sin embargo, esta investigación presenta algunas limitaciones. Este fue un estudio transversal, ya que los datos fueron recogidos en un único momento temporal. Sería deseable desarrollar investigaciones longitudinales que permitan conocer el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes a lo largo de toda la etapa secundaria. Además, las futuras investigaciones deberían incluir otras medidas del uso de las tecnologías y el rendimiento académico, además de los datos auto-informados por los estudiantes, cuando esto sea posible. También, sería recomendable llevar a cabo más estudios que investigaran de qué manera el uso de otras herramientas tecnológicas puede favorecer el rendimiento académico. Todo ello, con la finalidad de proporcionar una educación de calidad para los estudiantes adolescentes.

Apoyos

Estudio financiado por la Universidad de León (España). Ayuda para la realización de estudios de doctorado en el marco del programa propio de investigación para 2016-2020.

Referencias

Antonijevic, R. (2007). Usage of computers and calculators and students’ achievement: Results from TIMSS 2003. International Conference on Informatics, Educational Technology and New Media in Education, Sombor, Serbia. https://bit.ly/2A4HiQT

BOCYl (Ed.) (2015). Orden Edu/336/2015, de 27 de abril, por la que se regula el procedimiento para la obtención de la certificación en la aplicación de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación, por los centros docentes no universitarios, Valladolid, 2015-06-05 n. 84, 30622. https://bit.ly/2zzGsuZ

Cerezo, M.T., & Casanova, P.F. (2004). Diferencias de género en la motivación académica de los alumnos de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 2(3), 97-112. https://doi.org/10.25115/ejrep.3.125

Cetinkaya, L. (2017). The impact of WhatsApp use on success in education process. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7), 59-74. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i7.3279

Costa, S., & Tabernero, C. (2012). Rendimiento académico y autoconcepto en estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria según el género. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 2012, 3(2), 175-193. https://bit.ly/2ranaYF

Duart, J.M., Gil, M., Pujol, M., & Castaño, J. (2008). La universidad en la sociedad Red. Usos de la Internet en Educación Superior. Barcelona: Ariel.

García-Martín, J., & García-Sánchez, J.N. (2013). Patterns of Web 2.0 tool use among young Spanish people. Computers & Education, 67, 105-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.03.003

Gil, J. (2012). Utilización del ordenador y rendimiento académico entre los estudiantes españoles de 15 años. Revista de Educación, 357, 375-396. https://bit.ly/2U8VuAB

Gross, E.F., Juvonen, J., & Gable, S.L. (2002). Internet use and well-being in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 75-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00249

Han, I., & Shin, W.S. (2016). The use of a mobile learning management system and academic achievement of online students. Computers & Education, 102, 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.07.003

Jonassen, D.H., & Kwon, H. (2001). Communication patterns in computer mediated versus face-to-face group problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(1), 35-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02504505

Junco, R. (2015). Student class standing, Facebook use, and academic performance. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 36, 18-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.11.001

Kaiser, H.F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 32-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

Montes-Vozmediano, M., García-Jiménez, A., & Menor-Sendra, J. (2018). Teen videos on YouTube: Features and digital vulnerabilities. [Los vídeos de los adolescentes en YouTube: Características y vulnerabilidades digitales]. Comunicar, 54(26), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-06

Ndege, W., Mutavi, T., Kokonya, D., Nekesa, V., Musungu, B., Obondo, A., & Wangari, M. (2015). Social networks and students’ performance in secondary schools: Lessons form an Open Learning Centre, Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(21), 171-178. https://bit.ly/2DPqvDW

Noshahr, R., Talebi, B., & Mojallal, M. (2014). The relationship between use of cell-phone with academic achievement in female students. Applied Mathematics in Engineering, Management and Technology, 2(2), 424-428. https://bit.ly/2EiKmvB

Pantoja, A., & Huertas, A. (2010). Integración de las TIC en la asignatura de Tecnología de Educación Secundaria. Pixel-Bit, 37, 225-237. https://bit.ly/2P8klR7

Risso, A., Peralbo, M., & Barca, A. (2010). Cambios en las variables predictoras del rendimiento escolar en Enseñanza Secundaria. Psicothema, 22(4), 790-796. https://bit.ly/2Sglpob

Sheard, M. (2009). Hardiness commitment, gender, and age differentiate university academic performance. British Journal of Educational Society, 79, 189-204. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X304406

Soler-Adillon, J., Pavlovic, D., & Freixa, P. (2018). Wikipedia in higher education: Changes in perceived value through content contribution. [Wikipedia en la Universidad: Cambios en la percepción del valor con la creación de contenidos]. Comunicar, 54(26), 39-48. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-04

Tabatabai, D., & Shore, B.M. (2005). How experts and novices search the Web. Library & Information Science Research, 27(2), 222-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.005

Thurstone, L.L. (1947). Multiple factor analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Torres-Díaz, J.C., Duart, J.M., Gómez-Alvarado, H.F., Marín-Gutiérrez, I., & Segarra-Faggioni, V. (2016). Internet use and academic success in university students. Usos de Internet y éxito educativo en estudiantes universitarios]. Comunicar, 48(24), 61-70. https://doi.org/10.3916/C48-2016-06

Valkenburg, P.M., & Peter, J. (2007). Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Developmental Psychology, 43, 267-277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267

Wentwoth, D.K., & Middleton, J.H. (2014). Technology use and academic performance. Computers & Education, 78, 306-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.012

Wittwer, J., & Senkbeil, M. (2008). Is students’ computer use at home related to their mathematical performance at school? Computers & Education, 50, 1558-1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.03.001

Yuen, S.C., & Yuen, P.K. (2010). What teachers think about Web 2.0 technologies in education? 16th Annual Sloan Consortium International Conference Online Learning. Orlando, Florida. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.03.001

Document information

Published on 31/03/19

Accepted on 31/03/19

Submitted on 31/03/19

Volume 27, Issue 1, 2019

DOI: 10.3916/C59-2019-07

Licence: CC BY-NC-SA license

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?