(Created page with " ==Summary== ====Background==== Anastomotic leakage is a common complication after operative reconstruction with colon interposition in corrosive esophageal injury patients...") |

m (Scipediacontent moved page Draft Content 918838974 to Awsakulsutthi Havanond 2015a) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 12:40, 26 May 2017

Summary

Background

Anastomotic leakage is a common complication after operative reconstruction with colon interposition in corrosive esophageal injury patients. Because the underlying causes are ischemic in nature, vascular enhancement would resolve this complication.

Objective

To compare the incidence of anastomotic leakage between patients with and without vascular enhancement of esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective comparative study between patients with and without vascular enhancement during corrosive esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition in Thammasat University Hospital from January 2004 to December 2012.

Results

Twenty-five adult patients who received esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition for corrosive esophageal injury were included in this study. Eleven of these patients also received vascular enhancement (classified as the “with vascular enhancement” group) during the reconstruction, whereas the remaining 14 patients did not (classified as the “without vascular enhancement” group). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics of the patients between the two groups (i.e., sex, age, and preoperative hematocrit and serum albumin levels). There was also no significant difference in the leakage rate between the two groups: 35.7% (5/14) and 9% (1/11) in the without and with vascular enhancement groups, respectively (p = 0.180). However, in the “with vascular enhancement” group, the operative time was significantly longer (7.8 hours vs. 6.4 hours; an additional 1.4 hours), whereas length of hospital stay was shorter (18.3 days vs. 28.1 days; reduced by 9.8 days) compared with the other group.

Conclusions

Patients who received vascular enhancement along with colon interposition had a lower incidence of anastomotic leakage; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups in this study. Thus, further studies with a large sample size should be conducted in this regard.

Keywords

colon interposition;corrosive esophageal reconstructions;vascular enhancement

1. Introduction

Severe corrosive esophageal injury can cause loss of esophagus, which subsequently affects gastric functions, causing inability to swallow normally. Other associated problems are malnutrition and psychological disturbance to patients. Esophageal reconstructive surgery will solve these problems, and thus, improves the patients' quality of life.

However, performing esophageal reconstructions in cases with total loss of the esophagus and stomach following corrosive ingestion is a challenging problem. For this purpose, either the small or large bowel can be used. In a previous study, even interposition of the pedicle colon was used1; however, in almost all these patients, anastomotic leakage was a common postoperative complication. The incidence of pharyngeal anastomotic leakage was reported to be 5.6–14.2%,2 whereas in cases of corrosive ingestion, the rate is in the range of 23.9–26.48%.1 ; 3

Ischemic causes were believed to contribute significantly to this complication.4 With the advent of vascular anastomosis, vascular augmentation was adopted as a method to prevent ischemia-related problems. The objective of this study was motivated by the different results reported by previous studies on the effects of vascular enhancement.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to compare the incidence of anastomotic leakage between patients with and without vascular enhancement of esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition in Thammasat University Hospital (Pathum Thani, Thailand).

2. Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Thammasat University Hospital and Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University (MTU-EC-SU-0-098/56).

From January 2004 to December 2012, adult patients who were diagnosed with corrosive ingestion and had undergone esophageal reconstructive surgery with colon interposition in Thammasat University Hospital were reviewed.

All patients underwent esophagogastrectomy because of suicidal attempt and corrosive ingestion. The interval between esophagogastrectomy and esophageal reconstructive surgery was 6 months.5 All patients received nutrition support with jejunostomy feeding after esophagogastrectomy, which was continued even after the esophageal reconstructions until they could swallow normally. The patients were asked to stop smoking cigarettes after the esophagogastrectomy.

In the “without vascular enhancement” group, surgical procedures were carried out by general surgeons; however, in the “with vascular enhancement” group, the procedures were carried out by general surgeons and a plastic surgeon who performed vascular anastomosis. The sufficiency of the vascular enhancement was evaluated by the general surgeons. If poor distal blood flow was suspected (i.e., discolored distal bowel, slow or dark-colored arterial bleeding, mucosal swelling, overproduction of mucous), the blood flow was increased.

Baseline characteristics and the operative data of the patients (i.e., age, sex, history of smoking, preoperative hematocrit and serum albumin levels, part of colon used for reconstruction, and operative time) were collected and compared between the two groups.

The primary outcome of interest was pharyngeal anastomotic leakage, which was diagnosed by a barium swallowing study at the 14th postoperative day. The secondary outcome was hospital stay.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the patients were analyzed using mean and standard deviation or range according to the distribution of the data. A comparison of the baseline characteristics, operative data, and outcome (i.e., leakage rate and hospital stay) was carried out.

The Chi-square test was used for categorical data; however, if the expected value was <5% or >20%, then Fishers exact test was used instead. The t test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used for continuous data with normal and non-normal distributions, respectively. Variables that were significantly different between the two groups were adjusted while analyzing outcomes in multivariate analysis models. A p value <0.005 was considered to be statistically significant. STATA version 11 (Data Analysis and Statistical Software, STATA Corp LP, Texas, USA) was used for analysis.

3. Results

Twenty-five corrosive injury patients who received corrosive esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition were included in the study. Eleven of these patients also received vascular enhancement during the reconstruction, whereas the remaining 14 patients did not.

A comparison of the baseline characteristics of patients (i.e., age, sex, history of smoking, and preoperative serum albumin and hematocrit levels) between the two groups showed no significant difference (Table 1).

| Result | Without vascular enhancement (n = 14) | With vascular enhancement (n = 11) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 29.9 (10.01) | 23.7 (3.82) | 0.131 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 13 (92.9) | 9 (90.9) | 1.000 |

| Female | 1 (7.1) | 1 (9.1) | — |

| History of smoking, n (%) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Hct (%) | 37.9 (3.97) | 37.2 (3.12) | 0.642 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3.29 (0.31) | 3.26(0.13) | 0.622 |

| Colon conduit, n (%) | |||

| Left | 13 (92.9) | 9 (81.8) | 0.565 |

| Right | 1 (7.1) | 2 (18.2) | — |

| Operative time (h), mean (SD) | 6.4 (0.96) | 7.8 (1.05) | 0.002 |

| Anastomotic leakage (%) | 35.7 | 9.0 | 0.180 |

| Hospital stay, mean (d) | 28.1 (13.6) | 18.3 (1.42) | 0.039 |

| No leakage, mean (d) | 23.3 (9.86) | 18.0 (1.54) | 0.284 |

| Leakage, mean (d) | 36.6 (16.37) | 21.0 (–) | 0.379 |

| Dysphagia scorea, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 13 (92.9) | 9 (90.9) | 1.000 |

| 1 | 1 (7.1) | 1 (9.1) | — |

| >2 | — | — | — |

Hct = hematocrit; SD = standard deviation.

a. Based on the dysphagia scoring system by Mellow and Pinkas (Knyrim et al. 1993).6 Evaluation at 3 months after the operation.

The left side of the colon was commonly used for reconstruction in both groups: 13 patients (92.9%) in the group without vascular enhancement and nine patients (81.8%) in the group with vascular enhancement. Surgical reconstruction procedures in both groups were carried out via the substernal route. Proximal anastomosis was done at the cervical pharynx, and distal anastomosis was performed at the jejunum. The operative time was significantly longer (7.8 hours vs. 6.4 hours; an additional 1.4 hours) in the group that received vascular enhancement (p = 0.002; Table 1).

In the group that did not receive vascular enhancement, five of the 14 patients (35.7%) experienced pharyngeal anastomotic leakage: two patients had minor leakage that healed completely within 7 days with conservative treatment and three patients had major leakage that required neck incision for opening and drainage. These three patients were then treated conservatively, following after which their leakage healed completely. In the group with vascular enhancement, only one patient had minor pharyngeal anastomotic leakage (9.0%) that healed completely within 7 days with conservative treatment. The leakage rate between the two groups was not significantly different (p = 0.180; Table 1). There was no intra-abdominal anastomotic leakage in both groups.

The average length of hospital stay was 28.1 days for patients in the “without vascular enhancement” group and 18.3 days for those in the “with vascular enhancement” group. Five patients treated without vascular enhancement experienced anastomotic leakage, and the average length of their hospital stay was 36.6 (range, 20–61) days. One patient with pneumonia had the longest hospital stay (61 days). One patient treated with vascular enhancement still experienced anastomotic leakage, and had a hospital stay of 21 days.

Nine patients, without vascular enhancement and no anastomotic leakage, had an average hospital stay of 23.3 (range, 14–42) days. The other nine patients, with vascular enhancement and no anastomotic leakage, had an average hospital stay of 18 (range, 16–20) days.

At the 3-month follow up, there was no clinical pharyngeal anastomotic stricture. The dysphagia score between the two groups was not significantly different (Table 1).6 Long-term follow up was not conducted in this study.

4. Discussion

If the stomach is not available, the colonic flap or conduit is more appropriate for esophageal reconstruction because of the following reasons: straight shape, end-to-end anastomosis is possible to both at the pharynx (as proximal anastomosis) and jejunum (as distal anastomosis). Despite careful selection of patients for surgery and meticulous operative techniques, the incidence of pharyngeal anastomotic leakage is as high as 5.6–14.2%1 and in cases of corrosive ingestion the rate is in the range of 23.9–26.48%.2 ; 3 In this study, the incidence of pharyngeal anastomotic leakage was 35.7%.

Many believe that these complications are caused by ischemia. Some of the factors identified as being associated with the risk of ischemia are length of conduit, intra-abdominal fibrosis, route of passage of the conduit, and tension to the mesocolon.

It is difficult to perform esophageal reconstruction in patients with suicide corrosive ingestion, severe infection, and intra-abdominal fibrosis. In addition to the longer reconstruction time, fibrotic mesocolon and the surrounding area often remain following the procedure, causing tension to the mobilized pedicle colon, which eventually causes venous insufficiency.

Ischemic complications occur either from arterial insufficiency or are secondary to venous insufficiency.7 To prevent ischemic complications, enhancement of both arterial and venous vascularization should be considered.8 ; 9 Carefully planning these procedures improves operation time. The surgeon should select the long distal pedicle and anatomizes to the local vessels at same neck incision of pharyngeal anastomosis.

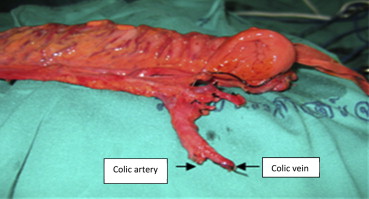

Vascular anastomosis can be performed under either microscopic or loupe magnifications. In clinical practice, these vascular skills can be performed by either the general surgeon or the plastic surgeon. To achieve a successful outcome, the distal vascular pedicle should be dissected meticulously and be as long as possible (Fig. 1). Proper donor vessels should be chosen carefully.

|

|

|

Figure 1. Preparing mesocolon pedicle for vascular enhancement (left arrow, colic artery; right arrow, colic vein). |

The possible options for donor artery are the transverse cervical artery, superior thyroid artery, and facial artery (Table 2). This was because, in most cases, the pulled-up colons had lots of surrounding adipose tissue. The transverse cervical artery was preferred in this study because it is easy to harvest and is longer in length. The artery also has a reliable fixed anatomic position. It lies on the prevertebral fascia (fascial carpet), and is easily found on the scalenus medius muscle before it enters the trapezius muscle. Its diameter is equal in proportion to the colonic artery. Because of its adequate length, anastomosis can clearly be performed without disturbing the colonic adipose tissue. For the donor vein, we chose to use the external jugular vein. This vein is located in the subcutaneous layer and is easy to harvest. In some cases the external jugular vein was damaged from the previous operation, and for these patients, the internal jugular vein was used for end-to-side anastomosis. Because the bowel veins were rather thin, upon completing anastomosis, their functionality and structural integrity, especially their double-walled structure, were completely verified.

| No. | Sex | Age (y) | Used colon | Donor artery | Donor vein | Operative time (h) | Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 33 | LC | TCA | EJV | 8.0 | No |

| 2 | Male | 24 | RC | TCA | EJV | 8.5 | No |

| 3 | Female | 24 | LC | TCA | EJV | 9.5 | No |

| 4 | Male | 20 | LC | STA | EJV | 7.5 | No |

| 5 | Male | 22 | RC | TCA | EJV | 9.0 | Leakage |

| 6 | Male | 18 | LC | TCA | EJV | 6.6 | No |

| 7 | Male | 22 | LC | TCA | EJV | 7.0 | No |

| 8 | Male | 25 | LC | TCA | EJV | 8.5 | No |

| 9 | Male | 24 | LC | TCA | EJV | 6.5 | No |

| 10 | Male | 26 | LC | TCA | EJV | 6.5 | No |

| 11 | Male | 23 | LC | STA | EJV | 8.0 | No |

EJV = external jugular vein; LC = left colon; RC = right colon; STA = superior thyroidal artery; TCA = transverse cervical artery.

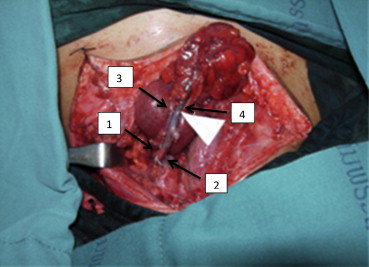

Vascular anastomosis should be done before pharyngeal anastomosis. Signs of good enhanced vascularization are brightening of dark-colored arterial bleeding, shrinking of mucosal swelling, and reduced production of mucous (Fig. 2).

|

|

|

Figure 2. Vascular anastomosis. Donor vessels: (1) transverse cervical artery; (2) external jugular vein. Recipient vessels: (3) colic artery; (4) colic vein. |

The results of this study show that enhanced vascularization requires more operative time but produces less complications compared with previous reports.10 The incidence of anastomotic leakage was also lower in patients receiving enhanced vascularization. However, its significant difference could not be proven, as this study included only a limited number of patients.

Alternative options for esophageal reconstructions include using gastric pull-up and extended colon interposition. If poor blood flow is suspected, augmentation of microvascular blood flow by applying one of these techniques can reduce the risk of leakage and partial necrosis.11; 12 ; 13

5. Conclusion

Vascular enhancement of corrosive esophageal reconstructions with colon interposition in adult patients lowered the incidence of anastomotic leakage, although no significant difference was found in this study. Therefore, further studies should be conducted to confirm this point.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their heartfelt thanks to Boonying Siribumrungwong, MD, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, for statistical advice.

References

- 1 J.D. Knezević, N.S. Radovanović, A.P. Simić, et al.; Colon interposition in the treatment of esophageal caustic strictures: 40 years of experience; Dis Esophagus, 20 (2007), pp. 530–534

- 2 J. Xia, Y. Peng, J. Huang, B.C. Cheng, Z.W. Wang; Prevention and treatment of anastomotic leakage and intestinal ischemia after esophageal replacement with colon; Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi, 12 (2009), pp. 17–19

- 3 J.H. Zhou, Y.G. Jiang, R.W. Wang, et al.; Management of corrosive esophageal burns in 149 cases; J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 130 (2005), pp. 449–455

- 4 J.H. Peters, J.W. Kronson, M. Katz, T.R. DeMeester; Arterial anatomic considerations in colon interposition for esophageal replacement; Arch Surg, 130 (1995), pp. 858–862 discussion 862–863

- 5 M. Chirica, N. Veyrie, N. Munoz-Bongrand, et al.; Late morbidity after colon interposition for corrosive esophageal injury: risk factors, management, and outcome. A 20-year experience; Ann Surg, 252 (2010), pp. 271–280

- 6 K. Knyrim, H. Wagner, N. Bethge, Keymling, N. Vakil; A controlled trial of an expansile metal stent for palliation of esophageal obstruction due to inoperable cancer; N Engl J Med., 78 (1993), pp. 1302–1307

- 7 H.D. Patel, Y.C. Chen, H.C. Chen; Salvage of right colon interposition by microsurgical venous anastomosis; Ann Thorac Surg, 74 (2002), pp. 921–923

- 8 K. Ueda, A. Kajikawa, Y. Suzuki, M. Okazaki, M. Nakagawa, S. Iida; Blood gas analysis of the jejunum in the supercharge technique: to what degree does circulation improve?; Plast Reconstr Surg, 119 (2007), pp. 1745–1750

- 9 Y. Shirakawa, Y. Naomoto, K. Noma, et al.; Interposition colon and supercharge for esophageal reconstruction; Langenbecks Arch Surg, 391 (2006), pp. 19–23

- 10 R.J. Cerfolio, M.S. Allen, C. Deschamps, V.F. Trastek, P.C. Pairolero; Esophageal replacement by colon interposition; Ann Thorac Surg, 59 (1995), pp. 1382–1384

- 11 M. Sekido, Y. Yamamoto, H. Minakawa, et al.; Variation of microvascular blood flow augmentation—supercharge in esophageal and pharyngeal reconstruction; Rozhl Chir, 85 (2006), pp. 9–13

- 12 H.I. Lu, Y.R. Kuo, C.Y. Chien; Extended left colon interposition for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction using distal-end arterial enhancement; Microsurgery, 28 (2008), pp. 424–428

- 13 S. Awsakulsutthi; Result of esophageal reconstruction using supercharged interposition colon in corrosive and Boehaves injury: Thammasat University Hospital experience; J Med Assoc Thai, 93 (2010), pp. S303–S306

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?