Summary

Background

To compare the efficacy and safety of both mechanical methods (clips) and electrosurgical instruments, harmonic scalpel (HS) and LigaSure (LS), for securing the cystic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC).

Methods

During the study period from October 2010 to October 2012, 458 patients with gallbladder stones underwent LC. A total of 38 patients were excluded from the study for different reasons. The gallbladder was excised laparoscopically through the traditional method. The gallbladder specimens of the patients were divided into three equal groups randomly, and the distal part of the cystic duct was sealed ex vivo using ligaclips (Group A), HS (Group B), and LS (Group C). The gallbladders were then connected to a pneumatic tourniquet device and we very gradually increased the pressure with air. The bursting pressure of the cystic duct (CDBP) was measured and differences between the three groups were calculated.

Results

The mean CDBP was 329.7 ± 38.8 mmHg in the ligaclip group, 358.0 ± 33.1 mmHg in the HS group, and 219.7 ± 41.2 mmHg in the LS group. A comparison of the mean CDBP between the groups indicated the superiority of HS over ligaclip and LS. CDBP was significantly higher in the ligaclips group compared with the LS group (p <0.001). HS and ligaclips were found to be safe sealers as their mean CDBP was found to be higher (>195 mmHg) than the maximum common bile duct pressure, whereas for LS the CDBP range was 150–297 mmHg, indicating that it is not safe for sealing.

Conclusion

HS is a safe alternative to clips. In fact, it was even safer than clips. By contrast, LS is not safe for cystic duct sealing.

Keywords

bile leakage;clips;harmonic scalpel;laparoscopic cholecystectomy;LigaSure

1. Introduction

Gallstone disease is common, and cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for symptomatic disease.1 Simple metal clips have been used by most surgeons to close the cystic duct since Professor Muhe reported the first successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) in 1985.2 However, these clips have been known to migrate into adjacent structures, lead to strictures due to a foreign body response, serve as a nidus for stone formation, and occasionally fall off and result in substantial morbidity.3

One problem with LC is the occurrence of postoperative cystic duct leakage (incidence rate, 0.6–2%), which may be related to insufficient closure of the cystic duct after the standard closure with two metal clips.4 Consequently, different techniques have been proposed for closing the cystic duct including using resorbable clips and performing ultrasonic dissection. In recent years, bipolar energy sources, such as LigaSure (LS), have been used for vascular sealing and investigated for closing the cystic duct.5

Contraction of the sphincter of Oddi is the major cause of common bile duct pressure (CBDP). The mean basic CBDP is 15 mmHg (range, 5–35 mmHg) and increases to 135 mmHg (range, 95–195 mmHg) during phasic contractions of the sphincter (4 times/min). Therefore, any sealing method that leads to bursting pressures of the cystic duct (CDBPs) > 195 mmHg could be reasonable.6

In the initial years of their use, there were insufficient data about the efficacy and safety of harmonic scalpel (HS) and LS for cystic duct sealing, especially about LS. Therefore, this study was carried out to verify the safety and efficacy of HS and LS for achieving safe closure of the cystic ducts after LC.

2. Materials and methods

Between October 2010 and October 2012, 458 patients with symptomatic gallbladder stones who were admitted to our university hospital were eligible for this prospective, randomized study. LC was performed at our hospital. The exclusion criteria included perforation of the gallbladder during surgery and acute cholecystitis. After obtaining informed consent from all patients to use their gallbladder specimens for the study, the specimens were sent for histopathological analysis. A total of 28 cases were excluded from the study due to perforation of the gallbladder during dissection (n = 17) and acute cholecystitis (n = 11). Ten specimens were excluded during pressure measurement studies. Thus, specimens from 420 patients were eligible. The eligible patients were randomized into three groups (according to the ex vivo cystic duct sealing method) using sealed envelopes. The envelopes were drawn and opened by an assistant who was not involved in this study before the operation. The three groups were as follows: (A) ligaclips, (B) HS, and (C) LS.

LC was performed under general anesthesia using the traditional four-port method in the “American” position. A pneumoperitoneum was created using a Veress needle with a maximized pressure of 15 mmHg. A zero-degree optic scope was used.

In all groups, LC was performed using the traditional method, which involved dissection of Calots triangle using a monopolar hook and then isolation of the cystic duct and cystic artery using curved dissecting forceps. Closure of the cystic duct was performed using (medium/large) 10-mm titanium ligaclips (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH), with two clips on the CBD side and one clip on the gallbladder side and then dividing it in between. The cystic artery was also clipped with two metal clips and divided in between. Mobilization of the gallbladder from the liver bed was completed using a monopolar hook. The gallbladder was retrieved with the ligaclips in situ after widening of the 10-mm port. Once the gallbladder is removed, it was prepared ex vivo for bursting pressure measurement.

In Group A, the ligaclip was removed and two fresh clips were placed to ensure that the fresh clips are competent.

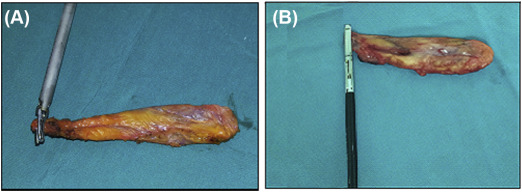

In Group B, the ligaclip was removed and the HS device was set at level 2 (less cutting and more coagulation). A harmonic ace laparoscopic instrument (Ethicon) was applied to the cystic duct at two levels, starting near the neck of the gallbladder first without complete division of the duct (8 peeps) and then reapplied more distally until the duct is cut completely (Fig. 1A).

|

|

|

Figure 1. (A) Sealing of the cystic duct using harmonic scalpel, (B) Sealing of the cystic duct using 5-mm LigaSure. |

In Group C, the ligaclip was removed and the cystic duct was sealed using a 5-mm LS laparoscopic instrument (Valleylab, Boulder, CO, USA) at two levels, with the generator set at level 2 and the instrument knife applied distally (Fig. 1B).

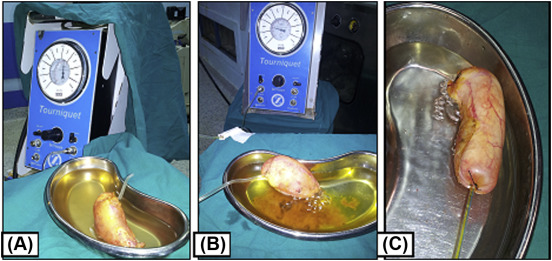

Then a 14-French catheter was inserted from the fundus of the gallbladder and fixed with two rings of purse string 2/0 silk suture. The catheter was connected to a pneumatic tourniquet device (WIKA, Cairo, Egypt). The collected gallbladder was then immersed in a saline-filled kidney dish. The pressure emerging from the tourniquet device was increased very slowly and steadily until air leakage (bubbling) was observed from the sealed cystic duct. At this point, the pressure in the tourniquet device was recorded as the bursting pressure (Fig. 2A–C). We excluded cases in which the bubbling occurred from places other the stump of the cystic duct (n = 10).

|

|

|

Figure 2. (A) Cystic duct sealed with harmonic scalpel just before leakage resisting pressure increased over 400 mmHg. (B) Air leakage from the cystic duct sealed with LigaSure started at 160 mmHg. (C) Air leakage from the cystic duct sealed with ligature. |

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 10.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Chi-square test was used for categorical variables and independent samples t test was used for continuous variables between the groups. A p value < 0.05 was taken to be significant.

3. Results

During the study period from October 2010 to October 2012, 458 patients with gallbladder stones underwent LC. A total of 38 patients were excluded from the study due to perforation of the gallbladder during dissection (n = 17) and acute cholecystitis (n = 11). Ten specimens were excluded because bubbling occurred from various places other than the stump of the cystic duct. Thus, a total of 420 patients were eligible and randomly divided into three equal groups based on the use of ligaclips, HS, and LS for closure of the cystic duct.

There was no statistically significant difference between groups regarding age, sex distribution, and comorbidities. The mean CDBP was 329.7 ± 38.8 mmHg in the ligaclip group, 358.0 ± 33.1 mmHg in the HS group, and 219.7 ± 41.2 mmHg in the LS group. A comparison of the mean CDBP between the groups indicated the superiority of HS over ligaclips and LS. CDBP was significantly higher in the ligaclip group compared with the LS group (p <0.001). HS and metal clips were found to be safe sealers as their mean CDBP was found to be higher (>195 mmHg) than the maximum CBDP unlike for LS where the CDBP range was 150–297 mmHg ( Table 1 ; Table 2).

| Ligature (n = 140) | HS (n = 140) | LS (n = 140) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 52 | 59 | 51 | 0.94 |

| Female | 88 | 81 | 89 | |

| DM | 33 | 29 | 28 | 0.78 |

| Cirrhosis | 19 | 17 | 23 | 0.31 |

DM = diabetes mellitus; HS = harmonic scalpel; LS = LigaSure.

| Bursting pressure (mmHg) Mean ± SD (range) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Clip | 329.7 ± 38.8 (220–382) | 0.004 |

| HS | 358.0 ± 33.1 (288–417) | |

| Clip | 329.7 ± 38.8 (220–382) | 0.000 |

| LS | 219.7 ± 41.2 (150–297) | |

| HS | 358.0 ± 33.1 (288–417) | 0.000 |

| LS | 219.7 ± 41.2 (150–297) |

HS = harmonic scalpel; LS = LigaSure; SD = standard deviation.

4. Discussion

Although rare, using clips in LC is associated with several complications such as ulcerating through the duodenum causing sever hemorrhage, embolism of clips, internalization of clips into the CBD, bile leak secondary to clip displacement, and clip-induced biliary stone.7 Leak from the cystic duct after using clips may be due to slippage of the clips and migration of clips into the biliary tract, necrosis of the duct at the site of clipping, or inadequate closure of the duct due to mismatch of the clip arms.8

Besides the common use of clips, various other techniques for securing the cystic duct and arteries have been introduced including ligature, HS, and LS. Shah and Maharjan7 used intracorporeal suturing for securing the cystic duct and artery in 80 patients undergoing LC. The authors stated that intracorporeal suturing is simple, safe, and economical with no cases of bile leak. Several recent reports had demonstrated that HS is a safe alternative to standard clipping of the cystic duct in LC. Some studies also documented the safety of HS that was associated with shorter operative time, less incidence of gallbladder perforation, and less postoperative pain.9 ; 10

The LS system has been shown to be effective for blood vessel sealing in many studies that compared it with monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar coagulation, or ultrasonic techniques.11 Recently, LS was used for resection or transection of various parenchymal organs and soft tissues, biliary duct closures, intestinal resection, and even for the closure of the appendicular stump during appendectomy.12

LS and HS have potential advantages over clips and ligature as they leave no metallic objects in the body and the risk of damage of the surrounding structures is minimal due to limited lateral thermal injury. However, the cost of the instrument is higher than that of the clip or ligature.5

Only a few studies have evaluated LS as a cystic duct sealer. Turial et al12 reported no bile leak after LS sealing of the cystic duct in 22 children receiving LC. The authors concluded that LS is a safe and effective sealer in children. Similarly, Schulze et al5 found that LS provided sufficient sealing of the cystic duct with no bile leak in 102 adult patients.

In our study, the mean CDBP was higher in the HS group than in the clip group with the minimum value (288 mmHg and 220 mmHg, respectively) higher than the maximum CBDP (195 mmHg), which means that they are safe for cystic duct sealing. The mean CDBP in the HS group was significantly higher than both ligaclip and LS groups, indicating that it is a safe cystic duct sealer. It was followed by clips, which had significantly higher mean CDBP than LS.

By contrast, the minimum CDBP was lower than the maximum CBDP in the LS group (150 mmHg), indicating that LS is not as safe as the other methods for sealing the cystic duct, especially if transcystic CBD exploration was done (which may lead to increase in the CBDP) and sealing of the cystic duct was desired without CBD decompression.

In conclusion, HS is a safe alternative to clips. In fact, it was even safer than clips. By contrast, LS is not safe for cystic duct sealing.

Acknowledgments

There was no funding received for the development of this article.

References

- 1 V.H. Chong, C.F. Chong; Biliary complications secondary to post-cholecystectomy clip migration: a review of 69 cases; J Gastrointest Surg, 149 (2010), pp. 688–696

- 2 A. Rohatgi, A.L. Widdison; An audit of cystic duct closure in laparoscopic cholecystectomies; Surg Endosc, 20 (2006), pp. 875–877

- 3 L.L. Swanstrom; “Clipless” cholecystectomy: evolution marches on, even for lap chole; World J Surg, 35 (2011), pp. 824–825

- 4 S. Schulze, V.B. Krisitiansen, B. Fischer Hansen, J. Rosenberg; Sealing of cystic duct with bipolar electrocoagulation; Surg Endosc, 16 (2002), pp. 342–344

- 5 S. Schulze, B. Damgaard, L.N. Jorgensen, S.S. Larsen, V.B. Kristiansen; Cystic duct closure by sealing with bipolar electrocoagulation; JSLS, 14 (2010), pp. 20–22

- 6 B. Kavlakoglu, R. Pekcici, S. Oral; Clipless cholecystectomy: which sealer should be used?; World J Surg, 35 (2011), pp. 817–823

- 7 J.N. Shah, S.B. Maharjan; Clipless laparoscopic cholecystectomy—a prospective observational study; Nepal Med Coll J, 12 (2010), pp. 69–71

- 8 K. Hanazaki, J. Igarashi, H. Sodeyama, Y. Matsuda; Bile leakage resulting from clip displacement of the cystic duct stump: a potential pitfall of laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Surg Endosc, 13 (1999), pp. 168–171

- 9 T. Kandil, A. El Nakeeb, E. El Hefnawy; Comparative study between clipless laparoscopic cholecystectomy by harmonic scalpel versus conventional method: a prospective randomized study; J Gastrointest Surg, 14 (2010), pp. 323–328

- 10 S.D. Patel, H. Patel, S. Ganapathi, N. Marshall; Day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy carried out using the harmonic scalpel: analysis of a standard procedure; Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, 20 (2010), pp. 20–23

- 11 T. Diamantis, M. Kontos, A. Arvelakis, et al.; Comparison of monopolar electrocoagulation, bipolar electrocoagulation, Ultracision, and Ligasure; Surg Today, 36 (2006), pp. 908–913

- 12 S. Turial, V. Engel, T. Sultan, F. Schier; Closure of the cystic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children using the LigaSure Vessel Sealing System; World J Surg, 35 (2011), pp. 212–216

Document information

Published on 26/05/17

Submitted on 26/05/17

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?