Emsupr2017 (talk | contribs) m (Corrected typos) (Tag: Visual edit) |

Emsupr2017 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

Este estudio se centra en el desarrollo de la simulación por elementos finitos del comportamiento de corte en el plano de cinchas tejidas fabricadas con fibras de Vectran. Se crea un modelo de simulación tridimensional con Simulia/Abaqus que reproduce el efecto de corte en el plano a partir de una fuerza axial. El modelo incluye interacciones de contacto, fricción, cargas de pretensado biaxial y el efecto de corte implementado experimentalmente. También se realizan una serie de estudios paramétricos para evaluar la influencia de los cambios en el nivel de pretensado y la fricción en la tensión de corte en función de la distorsión angular. Los resultados numéricos se comparan con evaluaciones experimentales para entender el comportamiento de corte del macro tejido creados a partir de cinchas entrelazadas. | Este estudio se centra en el desarrollo de la simulación por elementos finitos del comportamiento de corte en el plano de cinchas tejidas fabricadas con fibras de Vectran. Se crea un modelo de simulación tridimensional con Simulia/Abaqus que reproduce el efecto de corte en el plano a partir de una fuerza axial. El modelo incluye interacciones de contacto, fricción, cargas de pretensado biaxial y el efecto de corte implementado experimentalmente. También se realizan una serie de estudios paramétricos para evaluar la influencia de los cambios en el nivel de pretensado y la fricción en la tensión de corte en función de la distorsión angular. Los resultados numéricos se comparan con evaluaciones experimentales para entender el comportamiento de corte del macro tejido creados a partir de cinchas entrelazadas. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Palabras Clave: Cinchas, Cortante, Macro tejido, Vectran | ||

Revision as of 00:17, 15 April 2025

ABSTRACT

The development and construction of multilayered, high-strength membranes for large-scale inflatable structures requires understanding each layer's mechanical behavior. A typical multilayer configuration comprises a thin inner fabric layer that contains the inflation and pressurization fluid, air, or water, an intermediate fabric layer that protects the inner layer, and an external macro-fabric layer that provides mechanical strength to withstand membranal stresses resulting from the pressurization, as well as the effects of potential external forces. This macro-fabric usually comprises high-strength webbings interlaced in a plain weave pattern linked to the two inner layers at discrete connecting points.

Previous experimental studies using a "picture frame" configuration have been dedicated to evaluating shear behavior to account for the drapeability of the inflatable necessary to conform to the irregularities when deployed in confined environments. While experimental evaluations provided valuable information on the shear properties of woven webbings, only a few configurations can be evaluated.

This study focuses on the development of finite element simulation of the in-plane shear behavior of woven webbings manufactured with Vectran fibers. A three-dimensional simulation model is created with Simulia/Abaqus following the "picture frame" test configuration designed to produce an in-plane shearing effect from an axial force. The simulation model includes contact interactions, friction, biaxial pre-tensioning loads, and shearing effect implemented experimentally. A series of parametric studies are also conducted to assess the influence of changes in the pretension level and friction on the shear stress as a function of the angular distortion. Numerical results are compared with experimental evaluations, providing valuable insight into the shear behavior of macro-fabrics created from woven webbings.

Keywords: Fabric, Shear, Vectran, Woven Webbing.

RESUMEN

EVALUACIÓN NUMÉRICA DEL COMPORTAMIENTO DE CORTE EN EL PLANO DE CINCHAS ENTRETEJIDAS

El desarrollo y la construcción de membranas multicapa de alta resistencia para estructuras inflables a gran escala requieren comprender el comportamiento mecánico de cada capa. Una configuración multicapa típica consta de una fina capa interior que contiene el fluido de inflado y presurización (aire o agua), una capa intermedia que protege la capa interior y una capa externa en forma de macro tejido que proporciona resistencia mecánica para soportar las tensiones de la membrana resultantes de la presurización, así como los efectos de posibles fuerzas externas. Este macro tejido suele estar compuesto por cinchas de alta resistencia cruzadas en un patrón de entrelazado simple, unidas a las dos capas interiores en puntos de conexión discretos.

Estudios experimentales previos han evaluado el comportamiento al cortante en el plano para tener en cuenta la capacidad de drapeado del inflable, necesaria para adaptarse a las irregularidades al desplegarse en entornos confinados. Si bien las evaluaciones experimentales proporcionaron información valiosa sobre las propiedades de corte de las correas tejidas, solo se pueden evaluar algunas configuraciones.

Este estudio se centra en el desarrollo de la simulación por elementos finitos del comportamiento de corte en el plano de cinchas tejidas fabricadas con fibras de Vectran. Se crea un modelo de simulación tridimensional con Simulia/Abaqus que reproduce el efecto de corte en el plano a partir de una fuerza axial. El modelo incluye interacciones de contacto, fricción, cargas de pretensado biaxial y el efecto de corte implementado experimentalmente. También se realizan una serie de estudios paramétricos para evaluar la influencia de los cambios en el nivel de pretensado y la fricción en la tensión de corte en función de la distorsión angular. Los resultados numéricos se comparan con evaluaciones experimentales para entender el comportamiento de corte del macro tejido creados a partir de cinchas entrelazadas.

Palabras Clave: Cinchas, Cortante, Macro tejido, Vectran

1. Introduction

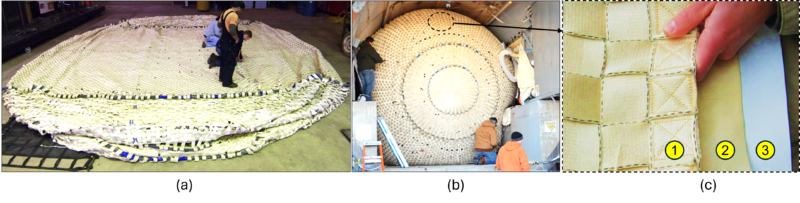

Large-scale, multilayered inflatable structures continue to be adopted to create habitats for spatial exploration [1–4] and to protect critical underground transportation infrastructure [5–15]. Depending on the inflatable's geometry and the required pressurization level, the inflatable can be subjected to high tensile membrane stress that can quickly exceed the material capacity [7]. To overcome this problem, multilayered fabric systems have been developed over the years to accommodate the different demands. In several applications, the inflatable membrane comprises multiple layers of fabric material that perform various functions depending on the specific structural demands or surrounding environment. For instance, space habitats require multiple layers to provide structural restraint to withstand pressurization, air tightness or gas barrier, radiation shield, orbital debris protection, and thermal protection [2]. In the case of inflatable structures for tunnel sealing, the number of layers can be reduced to a single fabric layer, as in the case of low-pressure (5 to 10 kPa or 0.05 to 0.1 bar) inflatables for containing the propagation of gases [5], or to three layers, as in the case of high-pressure designs (110 to 200 kPa or 1.1 to 2 bar) intended for containing water flooding [10–12]. Figure 1 shows an example of a large-scale inflatable structure tested experimentally in [10].

In space habitats or seals for infrastructure protection, the structural restrain must provide both membranal and puncture resistance when deployed in debris-filled or abrasive environments. This requirement prompted the implementation of macro fabrics comprised of straps, also known as webbings, woven in a plain tight or partially open plain weave fashion [2,12]. Among the high-strength fibers available commercially, fabrics, ropes, and webbings made of Vectran fibers [16,17] are commonly employed in highly demanding operational conditions. High-strength webbings made of Vectran fibers have been adopted in multiple applications due to their high strength and resistance to aggressive environments such as outer space or highly abrasive conditions [18,19].

From the structural point of view, the simulation of the mechanical behavior of a multilayered fabric system is not a trivial task. Unlike regular composite materials, fabric layers are not continuously bonded to each other via a bonding matrix. Typical designs include a series of discrete connections that connect layers, maintaining them in position during initial folding and packing for transportation and initial inflation for deployment and pressurization [10,20]. Moreover, not all the layers contribute to the membrane strength, but they do contribute to the mass of the system [14,15], which can be a critical factor in minimizing the weight launched into space or determining the most convenient placement for optimum deployment, particularly on applications designed to protect underground transportation infrastructure [10]. Previous simulations of multilayered, large-scale inflatables for infrastructure protection have adopted a simplified approach for finite element (FE) modeling the membrane. The three-layered membrane was modeled with an equivalent single-layer membrane with an equivalent thickness of 7.7 mm. About 91% of this equivalent thickness corresponds to the macro-fabric created from woven webbings and intended to carry the membrane stresses generated by the pressurization [14]. The remaining 9% corresponds to the two oversized inner layers containing the pressurization fluid. This approach has allowed the successful folding sequence simulation and initial deployment behavior [14].

Two critical aspects of FE simulation of macro-fabrics include the determination of tensile properties in the fill and warp directions, as well as the determination of the shear behavior of the woven webbings. In previous studies, the macro-fabric was represented by a fabric model available in Simulia/Abaqus [21] in which the biaxial tensile properties of the webbings were assumed to follow the same behavior obtained from uniaxial tensile tests. While adopting biaxial tensile properties obtained from uniaxial tests is typical for the representation of fabrics, limited information is available on the shear behavior of woven webbings. Therefore, this study explores the factors that affect the shear behavior of woven webbings, particularly those manufactured from Vectran fibers.

The main objective of this study is to develop a three-dimensional finite element model that simulates woven Vectran webbing under biaxial pretension and in-plane shear conditions. First, an overview of the previous experimental work that served as a reference for developing an FE model to represent the shear behavior of woven webbings is presented. The modeling approach and relevant features of the FE model are presented next, followed by a comparison and brief discussion of experimental and simulation results. The main observations and conclusions are presented at the end.

2. Overview of experimental investigations

2.1 Materials and picture frame test setup

Specimens for in-plane shear testing were manufactured using 50 mm wide, and 3.175 mm thick webbings manufactured with Vectran HT fibers [17]. The maximum tensile force an individual webbing can carry before failure is 107 kN [22]. This webbing type was previously used to manufacture the outer macro-fabric of the large-scale inflatable plug tested in [10,12] and the large-scale inflatable space habitat reported in [3].

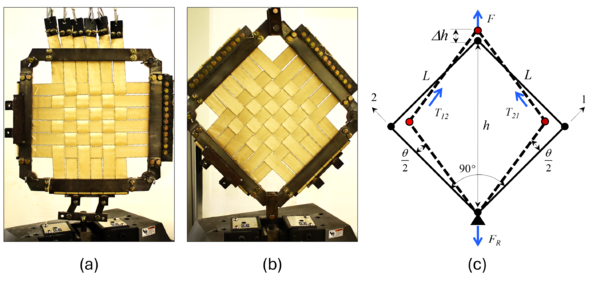

Shear testing specimens consisted of twelve 700 mm-long strips of webbing material cut from a roll of new material and then woven together, creating a six-by-six plain weave pattern with sufficient webbing lengths for attachment and pre-tensioning, as shown in Figure 2(a) [23]. The woven webbings were mounted into a customized test frame for the shear tests. This type of fixture is commonly used for shear testing of conventional fabric materials [24,25] and is also known as the "picture frame" test. The frame comprised four arms joined by corner pivots that allowed the rotation of the arms to reproduce a shearing effect on the plane of the frame. Each arm of the frame was 482.6 mm long by 50.8 mm wide and 12.7 mm thick, made of steel. These dimensions ensured the frame would have sufficient stiffness to hold the webbings during pretension in directions normal to the arms and during the in-plane shear testing. The frame corners were joined with solid 25.4 mm diameter hardened stainless steel smooth shafts. Two diagonally opposite shafts were also utilized to connect the frame to the testing machine via clevises, as shown in Figure 2(b).

2.2 Pre-tensioning and Shear test setup

Shear tests included three stages, as follows:

1) Pre-tensioning: In the first stage, pre-tensioning of webbing strips involved attaching one end of the webbing strips to the arms of the test frame. Six strips were laid side by side and positioned vertically, with the other strip attached to a pre-tensioning pulley system, which allowed independent movement of each pair of strips as shown in Figure 2(a). This configuration ensured uniform stress distribution across all strips when applying the pre-tensioning load. The frame and cable-pulley system were mounted in an Instron HDX1000 tensile testing machine to apply the pretension load by raising the machine crosshead while the bottom attachment was fixed. Each set of six webbings was pretensioned to a total initial load of 22 kN, which, because of the relaxation of the individual webbings during the mounting procedures, was reduced to 18 kN while completing the final clamping. With this level of pre-loading, each webbing was subject to about 3 kN, about 3% of the ultimate individual webbing maximum tensile force. The same procedure was implemented for the second set of six webbings interwoven and in a perpendicular direction to the first set.

2) In-plane shear test: Once the pre-tensioning was completed, the shear test frame was remounted into the testing machine, but now from two diagonally opposite corners, which, when pulled by the machine crosshead, would produce a shearing effect on the woven webbings. Figure 2(b) shows the shear test specimen's initial position. The shearing effect was created by applying a quasi-static vertical displacement of the crosshead at 0.76 mm/sec up to a maximum stroke of 130 mm. The machine data acquisition system recorded the resulting tensile force to produce this displacement. The vertical lifting of the top corner resulted in the specimen deforming into a progressively elongated diamond shape, as schematized in Figure 2(c). The force and vertical displacement were later used to calculate the resulting nominal shear stress and angular distortion.

3) Angular distortion and shear stress calculations: Figure 2(c) presents a schematic representation of the forces, distances, and angles utilized to calculate the angular distortion and shear stress. These two quantities were determined according to equation 1 and equation 2, respectively, and as follows:

|

|

(1) | |

|

|

(2) |

In equation 1, the total angular distortion () is determined by the difference between the angle at the original position (90°) and the change in angle due to the force action. The change in angle is a function of the increase (h) in the distance between pivot points (h = 682.5 mm) and the length of the frame arms (L = 482.6 mm). The distance h is provided by the vertical movement of the machine's crosshead. Also, equation 2 provides an estimation of the nominal in-plane shearing stress (T12) as a function of tensile force F measured by the testing machine load cell, the woven webbing material thickness (t = 6.35 mm, corresponding to two webbings thicknesses), the frame arm length (L = 482.6 mm), and half the angular distortion () calculated in equation 1. The experimental average angular distortion vs. shear stress graph was utilized as a reference for comparison with the results obtained from the FE simulations.

3. Finite Element Model

The experimental setup presented in the previous section was used to create a three-dimensional FE model. The Simulia/Abaqus simulation package [21] was adopted for the development of the FE model, which included the following steps:

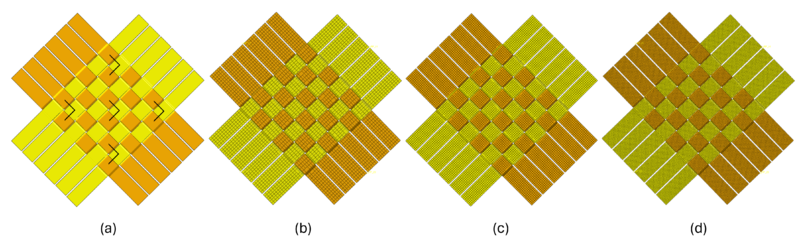

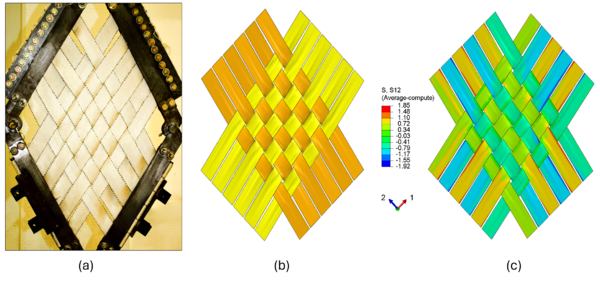

1) Geometry and assembly: The geometry of the woven webbing replicated the actual dimensions of webbings used in experimental tests. The model was created by designing and replicating a single strap to form a woven webbing structure of twelve interlaced straps, with six in each direction (fill and warp), as shown in Figure 3(a).

2) Material properties: The Fabric material model available in [21] with a membrane section with a thickness of a single webbing was implemented to simulate the behavior of a macro fabric. Force-displacement curves obtained from uniaxial tests performed on single Vectran webbings [18,22] were used for the parameters needed for the Fabric material model. This material model captures the mechanical response of fabrics phenomenologically, allowing for independently adjusting structural directions and shear properties [21]. This material model was also adopted to simulate the full-scale inflatables reported in [14,15].

3) Interactions: The interactions between the straps were defined using the general contact interaction type and applying friction via the penalty method, which considers only a static friction coefficient, and the exponential decay method, which considers the static and kinematic friction coefficients [21]. Contacts between the upper and lower surfaces of the straps were also specified, creating sets and couplings to group the surfaces and facilitate the application of interactions.

4) Boundary conditions and loads: The biaxial pretension and shearing effects were uniformly distributed into the woven webbing through reference points and couplings. A displacement control approach was adopted to apply the pretension as well as the shearing effect. The pretension ranged from 5 to 6 mm applied biaxially, followed by a shearing displacement of 60 mm on two sides of the frame to reproduce the shearing effect. This level of displacement produced reaction forces calculated by the FE model that were comparable to the forces measured experimentally. The boundary conditions for each type of load included fixing the ends of the straps to ensure an accurate simulation of loading conditions.

5) Mesh: The mesh comprised quadrilateral membrane elements with reduced integration (M3D4R). A mesh sensitivity analysis was conducted by creating four different meshes with varying element densities (5328, 11328, and 23904 elements, shown in Figures 3(b) to (d)). The sensitivity analysis showed that the solution converged and became nearly independent of the mesh size, starting from the mesh of 11328 elements. The angular distortion was monitored following the angle change in five initial right angles located at the center and corners of the woven webbings, as shown in Figure 3(a).

4. Results and discussion

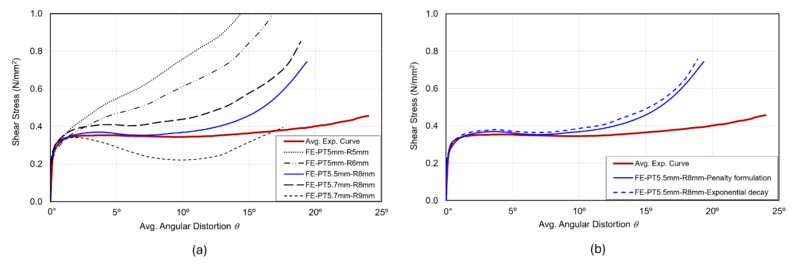

Figure 4(a) shows the average shear stress vs. angular distortion obtained experimentally and calculated with equations 1 and 2, and the shear stress vs. average angular distortions obtained from the FE simulations. The experimental curve displayed a distinct behavior that included a quick increase in the shear stress exhibited by a steep slope for small angular distortions (< 2°), followed by a plateau for angles between 2° and 15°, and a moderate increase of shear stress for angles larger than 15°. This behavior is attributed to the initial force needed to break the shear resistance generated by the static friction resulting from the contact among the webbings, as well as the intrinsic friction of the test frame. Once the static friction is overcome, the kinematic friction coefficient, typically smaller than the static friction, comes into play, and the shearing force to deform the woven webbings does not increase significantly. For distortional angles higher than 15°, the webbings start to pull together laterally, producing an increase in the shearing stress. The shape and magnitude of the experimental curve shown in Figure 4(a) were used to compare with the results computed by the FE model.

Several preliminary FE runs were conducted, varying the amount of pretension, and subsequent shear was applied through a displacement control method to reproduce the experimental curve. Initially, various levels of pretension were analyzed while keeping shear displacement constant, observing that an increase in pretension consistently resulted in a steeper slope of the shear stress curves at smaller angular distortions. Subsequently, shear levels were also varied while keeping pretension constant, finding a significant increase in shear stresses and angular distortions that did not correlate well with experimental measurements. Additionally, combinations of pretension and shear with variable reductions of the initial pretension were also explored, concluding that a reduction in the webbings' pretensioning was taking place while the shearing displacements were applied, resulting in a decrease in shear stress, bringing the results closer to the experimental ones. Figure 4(a) shows a parametric study varying the amplitude of the pretension (PT) in terms of displacement control from 5 to 5.7 mm while applying a shearing displacement of 60 mm, reducing (R) the pretension from 5 mm to 9 mm, and maintaining a constant static friction coefficient of 0.4. Results show that an initial pretension of 5.7 mm and a subsequent reduction of 8 mm, during which a shear of 60 mm is applied, provided a shear stress curve that approximated the experimental one, especially at angular distortions of less than 15°. These results strongly suggest that the frame could not maintain the pretension while the shearing effect was applied. This limitation was also observed by Bassett and Postle [24], indicating that stress relaxation produced during the pause to transition from the pretensioning stage to the shearing stage can create a non-homogenous state of strain.

The influence of the friction coefficient was also evaluated by accounting for the variation of the friction coefficient from static to dynamic values. Figure 4(b) shows two cases: one with a constant static friction coefficient of 0.4, a second with a static friction of 0.4, and a dynamic friction coefficient of 0.35 with a decay coefficient of 0.05, following an exponential decay model [21]. Results plotted in Figure 4(b) indicate that including the dynamic friction coefficient does not significantly change the shape or amplitude of the shear vs. angular distortion FE curves. Results summarized in Figure 4 suggest that the FE model is more sensitive to the level of pretension and loss of it rather than the transition from static to dynamic friction coefficients. Additional parametric studies are being conducted to assess the friction coefficient's influence further.

Figures 5(a) and 5(b) show the good agreement between the deformed shapes obtained experimentally and those predicted by the FE model at the end of the shearing stages at an angular distortion of about 20°. Notably, the FE model captures the bunching up of the webbings in both directions seen in the experiments. It is speculated that at this stage, the FE model tended to overpredict the shear stresses (seen in angles higher than 10° in Figure 4) due to the estimated compressibility assigned (1% of the tensile properties) to the Fabric material model. Hence, it can better capture the formation of wrinkles as the shearing effect progresses. Further parametric studies are being conducted to fine-tune the material model. Finally, Figure 5(c) shows the shear stress distribution predicted by the FE model at the end of the shearing effect. Results show that shear stress values ranged from -0.41 to +0.34 MPa in the central region of the woven webbings. This range is in close proximity to the experimental shear stress seen in the plateau region (0.36 MPa) of Figure 4.

5. Conclusions

A FE model capable of reproducing the in-plane shear behavior of woven webbings is implemented, and its performance is compared to experimental evaluations conducted using the "picture frame" test. The FE model can represent pretensioning and shear effects following a displacement control method that results in close agreement between simulation and experimental results.

The influence of initial total pretension and friction coefficient among woven webbings were analyzed. Simulation results indicated that the magnitude of the in-plane shear stress is more sensitive to the pretension level than the friction coefficient as the distortional angle increases. Additionally, the FE model allowed us to determine that the pretension load applied during the experiment tests was likely further reduced during the transition from the pretensioning stage to the shearing stage, thus influencing the amplitude of the shear stresses. Despite this limitation, the combination of experimental and FE results provided valuable insights into the shear behavior of woven webbings.

6. References

[1] J. Kozicki, J. Kozicka, Human friendly architectural design for a small Martian base, Adv. Space Res. 48 (2011) 1997–2004. DOI:10.1016/j.asr.2011.08.032.

[2] D. Litteken, K. Shariff, D. Calderon, M. Sico, C. Gaytan, M. O’Donnell, Design of a Microgravity Hybrid Inflatable Airlock, in: 2020 IEEE Aerosp. Conf., IEEE, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2020: pp. 1–17. DOI:10.1109/AERO47225.2020.9172313.

[3] Sierra Space, Sierra Space Advances its Revolutionary Commercial Space Station Technology, Website Post (2024). https://www.sierraspace.com/press-releases/sierra-space-advances-its-revolutionary-commercial-space-station-technology/ (accessed March 3, 2025).

[4] L. Tenorio, T. Yokozeki, J. Sato, Structural design of Super Pressure Balloon Habitat on the moon, Acta Astronaut. 195 (2022) 183–203. DOI:10.1016/j.actaastro.2022.02.031.

[5] X. Martinez, J. Davalos, E.J. Barbero, E.M. Sosa, W. Huebsch, K. Means, L. Banta, G. Thompson, Inflatable Plug for Threat Mitigation in Transportation Tunnels, in: Proc. SAMPE 2012 Conf. Exhib., 2012.

[6] H. Fountain, Creating a Balloon-like Plug to Hold Back Floodwaters, N. Y. Times Sci. Suppl. (2012).

[7] E.J. Barbero, E.M. Sosa, X. Martinez, J.M. Gutierrez, Reliability design methodology for confined high pressure inflatable structures, Eng. Struct. 51 (2013) 1–9. DOI:10.1016/j.engstruct.2013.01.011.

[8] E.J. Barbero, E.M. Sosa, G.J. Thompson, Testing of Full-Scale Confined Inflatable for The Protection of Tunnels, in: Proc. VI Int. Conf. Text. Compos. Inflatable Struct. Struct. Membr., 2013.

[9] E.M. Sosa, G.J. Thompson, E.J. Barbero, S. Ghosh, K.L. Peil, Friction characteristics of confined inflatable structures, Friction 2 (2014) 365–390. DOI:10.1007/s40544-014-0069-8.

[10] E.M. Sosa, G.J. Thompson, E.J. Barbero, Testing of Full-Scale Inflatable Plug for Flood Mitigation in Tunnels, Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2407 (2014) 59–67. DOI:10.3141/2407-06.

[11] E.M. Sosa, G.J. Thompson, E.J. Barbero, Experimental investigation of initial deployment of inflatable structures for sealing of rail tunnels, Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 69 (2017) 37–51. DOI:10.1016/j.tust.2017.06.001.

[12] E.M. Sosa, G.J. Thompson, G.M. Holter, J.M. Fortune, Large-scale inflatable structures for tunnel protection: a review of the Resilient Tunnel Plug project, J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 1 (2020) 11. DOI:10.1186/s43065-020-00011-0.

[13] J. Chen, Y. Zheng, X. Zhong, S. Yan, F. Li, Working mechanism and testing of emergency reinforced airbag used for blocking in tunnels, Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 138 (2023) 105201. DOI:10.1016/j.tust.2023.105201.

[14] E.M. Sosa, J.C.-S. Wong, A. Adumitroaie, E.J. Barbero, G.J. Thompson, Finite element simulation of deployment of large-scale confined inflatable structures, Thin-Walled Struct. 104 (2016) 152–167. DOI:10.1016/j.tws.2016.02.019.

[15] I. Pecora, E.M. Sosa, G.J. Thompson, E.J. Barbero, FE simulation of ceiling deployment of a large-scale inflatable structure for tunnel sealing, Thin-Walled Struct. 140 (2019) 272–293. DOI:10.1016/j.tws.2019.03.043.

[16] D.E. Beers, J.E. Ramirez, Vectran High-Performance Fibre, J. Text. Inst. 81 (1990) 561–574. DOI:10.1080/00405009008658729.

[17] Kuraray, https://www.kuraray.co.jp/vectran/en/product/index.html, 2025.

[18] T.C. Jones, W.R. Doggett, Time-Dependent Behavior of High Strength Kevlar and Vectran Webbing, in: 55th AIAAASMEASCEAHSASC Struct. Struct. Dyn. Mater. Conf., American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, National Harbor, Maryland, 2014. DOI:10.2514/6.2014-1328.

[19] S. Kenner, Long Term Displacement Data of Woven Fabric Webbings under Constant Load for Inflatable Structures, in: 55th AIAAASMEASCEAHSASC Struct. Struct. Dyn. Mater. Conf., American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, National Harbor, Maryland, 2014. DOI:10.2514/6.2014-0352.

[20] J. Hinkle, R. Timmers, A. Dixit, J. Lin, J. Watson, Structural Design, Analysis, and Testing of an Expandable Lunar Habitat, in: 50th AIAAASMEASCEAHSASC Struct. Struct. Dyn. Mater. Conf., American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Palm Springs, California, 2009. DOI:10.2514/6.2009-2166.

[21] Dassault Systèmes Americas Corp., Abaqus User’s Manual, Documentation Collection, Version 2024, Waltham MA, (2024).

[22] K.L. Peil, Material Characterization and Analysis of Vectran Fabrics and Webbings for Inflatable Structure Applications, West Virginia University, 2012.

[23] K.L. Peil, E.J. Barbero, E.M. Sosa, Experimental Evaluation of Shear Strength of Woven Webbings, in: Proc. SAMPE 2012 Conf. Exhib., 2012.

[24] R.J. Bassett, R. Postle, N. Pan, Experimental Methods for Measuring Fabric Mechanical Properties: A Review and Analysis, Text. Res. J. 69 (1999) 866–875. DOI:10.1177/004051759906901111.

[25] Philippe Boisse, Bassem Zouari, Jean-Luc Daniel, Importance of in-plane shear rigidity in finite element analyses of woven fabric composite preforming, Compos. Part A 37 (2006) 2201–2212. DOI:10.1016/j.compositesa.2005.09.018.

Document information

Accepted on 21/07/25

Submitted on 12/05/25

Licence: Other

Share this document

Keywords

claim authorship

Are you one of the authors of this document?